JUDGMENT OF THE COURT OF FIRST INSTANCE (Second Chamber)

15 March 2006 (*)

(Community trade mark – Three-dimensional mark – Shape of a plastic bottle – Refusal of registration – Absolute ground of refusal – Lack of distinctive character – Earlier national trade mark – Paris Convention – TRIPS Agreement – Article 7(1)(b) of Regulation (EC) No 40/94)

In Case T-129/04,

Develey Holding GmbH & Co. Beteiligungs KG, established in Unterhaching (Germany), represented by R. Kunz-Hallstein and H. Kunz-Hallstein, lawyers,

applicant,

v

Office for Harmonisation in the Internal Market (Trade Marks and Designs) (OHIM), represented by G. Schneider, acting as Agent,

defendant,

ACTION for annulment of the decision of the Second Board of Appeal of OHIM of 20 January 2004 (Case R 367/2003-2) rejecting the application for registration as a Community trade mark of a three-dimensional sign in the form of a bottle,

THE COURT OF FIRST INSTANCEOF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES (Second Chamber),

composed of J. Pirrung, President, A.W.H. Meij and I. Pelikánová, Judges,

Registrar: C. Kristensen, Administrator,

having regard to the application lodged at the Registry of the Court of First Instance on 1 April 2004,

having regard to the response lodged at the Registry of the Court of First Instance on 28 July 2004,

having regard to the Court’s written questions to the parties of 23 May 2005,

further to the hearing on 12 July 2005,

gives the following

Judgment

Background to the dispute

1 On 14 February 2002, the applicant filed an application with the Office for Harmonisation in the Internal Market (Trade Marks and Designs) (OHIM) for a Community trade mark pursuant to Council Regulation (EC) No 40/94 of 20 December 1993 on the Community trade mark (OJ 1994 L 11, p. 1), as amended, claiming priority for an original filing in Germany on 16 August 2001.

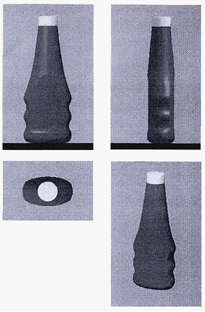

2 The application concerned registration of a three-dimensional sign in the shape of a bottle and reproduced below (‘the mark sought’):

3 The goods in respect of which registration of the sign was sought are in Classes 29, 30 and 32 of the Nice Agreement concerning the International Classification of Goods and Services for the Purposes of the Registration of Marks of 15 June 1957, as revised and amended, and correspond for each class to the following descriptions:

– Class 29: ‘Peppers, tomato concentrate, milk and milk products, yoghurt, crème fraîche, edible oils and fats’;

– Class 30: ‘Spices ; seasonings; mustard, mustard products; mayonnaise, mayonnaise products; vinegar, vinegar products; drinks made using vinegar; remoulades; relishes; aromatic preparations for food and essences for foodstuffs; citric acid, malic acid and tartaric acid used for flavouring for foodstuffs; prepared horse-radish; ketchup and ketchup products, fruit coulis; salad sauces, salad creams’;

– Class 32: ‘Fruit drinks and fruit juices; syrup and other preparations for drinks’.

4 By decision of 1 April 2003 the examiner rejected the application for registration pursuant to Article 7(1)(b) of Regulation No 40/94. The examiner held, firstly, that OHIM was not bound by earlier national registrations and, secondly, that the shape of the mark sought had no particular and clearly identifiable element permitting it to be distinguished from the usual shapes available on the market and giving it the function of indicating its commercial origin.

5 The appeal brought by the applicant, based inter alia on the unusual and individual nature of the bottle in question, was dismissed by the Second Board of Appeal by decision of 20 January 2004 (‘the contested decision’). The Board of Appeal endorsed the reasoning of the examiner. It added that, in the case of a trade mark consisting of the shape of the packaging, it was necessary to take into account the fact that the perception of the relevant public was not necessarily the same as in the case of a word mark, a figurative mark or a three-dimensional mark unrelated to the look of the product which it covers. The end consumer would usually pay more attention to the label attached to the bottle than to the mere shape of the bare and colourless container.

6 The Board of Appeal noted that the trade mark sought had no additional feature enabling it clearly to be distinguished from the usual shapes available and to remain in the memory of consumers as an indication of origin. It took the view that the particular perception referred to by the applicant would appear only after a detailed analytical examination which the average consumer would not undertake.

7 Finally, the Board of Appeal noted that the applicant could not rely on the registration of the trade mark sought on the German trade mark register since a national registration, although it may be taken into consideration, is not decisive. Furthermore, according to the Board of Appeal, the registration documents submitted by the applicant did not state the grounds on which the registration of the mark in question had been granted.

Forms of order sought

8 The applicant claims that the Court should:

– annul the contested decision;

– order OHIM to pay the costs.

9 OHIM contends that the Court should:

– dismiss the application;

– order the applicant to pay the costs.

Law

10 The applicant puts forward four pleas in law, based respectively on OHIM’s failure to discharge the burden of proof, which constitutes a breach of Article 74(1) of Regulation No 40/94 (first plea), failure to apply Article 6 quinquies (A)(1) of the Paris Convention for the Protection of Industrial Property of 20 March 1883, as last revised at Stockholm on 14 July 1967 and amended on 28 September 1979 (United Nations Treaty Series, Vol. 828, No 11847, p. 108, ‘the Paris Convention’), since OHIM deprived the earlier national registration of protection (second plea), breach of Article 73 of Regulation No 40/94, Article 6 quinquies of the Paris Convention and Article 2(1) of the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights, including trade in counterfeit goods, of 15 April 1994 (‘the TRIPs Agreement’), since OHIM failed sufficiently to examine the earlier national registration (third plea), and breach of Article 7(1)(b) of Regulation No 40/94, since OHIM failed to recognise the distinctive character of the mark sought and the fact that its features have no technical function (fourth plea).

The first plea in law, alleging breach of Article 74(1) of Regulation No 40/94

Arguments of the parties

11 The applicant takes the view that the Board of Appeal failed to fulfil its obligation under Regulation No 40/94 to prove the lack of distinctive character when it noted that the shape in question would be perceived as that of a common bottle and not as an indicator of commercial origin without supporting its conclusion with concrete examples. The applicant submits that it is for OHIM, which is required to examine the facts of its own motion in the context of assessment of the existence of absolute grounds for refusal, to establish whether the trade mark sought is devoid of distinctive character. It is only if OHIM can prove that the trade mark sought is devoid of intrinsic distinctive character that the applicant for registration may then show that it has acquired distinctive character through use.

12 At the hearing, the applicant added that the fact that the burden of proof lies on OHIM also follows from Article 6 quinquies of the Paris Convention. According to the applicant, that article stipulates that protection of a trade mark registered in a State signatory to the Paris Convention is to be the rule, refusal of protection being an exception which must be interpreted strictly.

13 OHIM disputes the arguments of the applicant, noting that the examination of the facts of its own motion is unrelated to the burden of proof. It adds that it cannot be required to prove a negative, namely the absence of distinctive character. Finally, referring to the case-law of the Court of First Instance, OHIM submits that, with regard to the lack of distinctive character, it is subject only to the obligation to give reasons. In the same way, OHIM takes the view that it is clear from the case-law that it may rely on general information based on experience, as was the case in the present matter, and that it is for the applicant for registration, as necessary, to provide specific and substantiated information on the perception by the relevant consumers of certain signs as indications of commercial origin.

Findings of the Court

14 Firstly, it should be observed that the reference to the Paris Convention, made by the applicant at the hearing, is irrelevant. Article 6 quinquies of the Convention, which deals with the protection and registration of trade marks in another State signatory to the Paris Convention, contains no provisions governing the allocation of the burden of proof in proceedings for registration of Community trade marks.

15 Secondly, it should be noted that, in the context of examination of the existence of absolute grounds for refusal under Article 7(1) of Regulation No 40/94, the role of OHIM is to decide, after having assessed, objectively and impartially, the circumstances of the case in question in the light of the applicable rules of Regulation No 40/94 and the interpretation thereof given by the Community Courts, whilst allowing the applicant to submit its observations and to know the reasons for the decision adopted, whether the application for the trade mark falls under an absolute ground of refusal. That decision follows from a legal assessment which, by its very nature, cannot be subject to an obligation of proof, the basis of that assessment being, moreover, liable to be contested if an action is brought before the Court (see paragraph 18 below).

16 Pursuant to Article 74(1) of Regulation No 40/94, when considering the grounds of absolute refusal, OHIM is required to examine of its own motion the relevant facts which may lead it to apply an absolute ground of refusal.

17 If OHIM finds that there are facts justifying the application of an absolute ground of refusal, it is required to inform the applicant for registration thereof and to allow it the opportunity of withdrawing or amending the application or of submitting its observations, pursuant to Article 38(3) of the above regulation.

18 Finally, if it is minded to refuse the application for a trade mark on the basis of an absolute ground of refusal, OHIM is required to give reasons for its decision pursuant to the first sentence of Article 73 of the regulation. The giving of reasons has two purposes: to allow interested parties to know the justification for the measure so as to enable them to protect their rights and to enable the Community judicature to exercise its power to review the legality of the decision (see Joined Cases T‑124/02 and T‑156/02 Sunrider v OHIM – Vitakraft-Werke Wührmann and Friesland Brands (VITATASTE and METABALANCE 44) [2004] ECR II‑1149, paragraphs 72 and 73, and the case-law cited).

19 Thirdly, it should be noted that, where the Board of Appeal finds that the trade mark sought is devoid of intrinsic distinctive character, it may base its analysis on facts arising from practical experience generally acquired from the marketing of general consumer goods which are likely to be known by anyone and are in particular known by the consumers of those goods (see, by analogy, Case T‑185/02 Ruiz‑Picasso and Others v OHIM – DaimlerChrysler (PICARO) [2004] ECR II-1739, paragraph 29). In such a case, the Board of Appeal is not obliged to give examples of such practical experience.

20 It is on that acquired experience that the Board of Appeal relied when it held, in paragraph 52 of the contested decision, that the relevant consumers would perceive the trade mark sought as a normal bottle intended to hold drinks, condiments and liquid foodstuffs and not as the trade mark of a particular manufacturer.

21 Since the applicant claims that the trade mark sought is distinctive, despite the analysis of the Board of Appeal based on the abovementioned experience, it is for the applicant to provide specific and substantiated information to show that the trade mark sought has either an intrinsic distinctive character or a distinctive character acquired by usage, since it is much better placed to do so, given its thorough knowledge of the market (see, to that effect, Case T‑194/01 Unilever v OHIM (Oval tablet) [2003] ECR II‑383, paragraph 48).

22 It follows that the applicant errs in submitting that, by failing to give such indications, the Board of Appeal breached Article 74(1) of Regulation No 40/94. The first plea in law must therefore be rejected.

The second plea in law, alleging breach of Article 6 quinquies (A)(1) of the Paris Convention

Arguments of the parties

23 The applicant submits that, by deciding that the trade mark sought was devoid of distinctive character on Community territory, OHIM in essence considered invalid and thus deprived of protection on German territory the earlier German trade mark protecting the same sign, registered by the Deutsches Patent- und Markenamt (German Patent and Trade Mark Office). The applicant takes the view that OHIM’s conduct constitutes a breach of Article 6 quinquies (A)(1) of the Paris Convention, which prohibits OHIM from declaring that the trade mark may not be protected on the territory of the State signatory to the Paris Convention in which it was registered.

24 OHIM submits that Article 6 quinquies (A)(1) of the Paris Convention stipulates that the trade mark registered in the country of origin is to be protected abroad as is, namely as it was registered, subject to the reservations stated in the article. Article 6 quinquies (B)(ii) expressly provides for refusal of registration where there is a lack of distinctive character. It adds that the refusal of registration of a Community trade mark does not entail annulment of a national registration protecting the same sign.

Findings of the Court

25 Assuming that OHIM is required to comply with Article 6 quinquies of the Paris Convention, it should be noted, firstly, that it is on an incorrect premiss that the applicant bases its assertion that OHIM declared invalid an existing registration in a State signatory to the Paris Convention. Pursuant to the fifth recital in the preamble to Regulation No 40/94, the Community law relating to trade marks does not replace the laws of the Member States on trade marks. Accordingly, the contested decision, by which registration of the trade mark sought as a Community trade mark was refused, affects neither the validity nor the protection on German territory of the earlier national registration. It follows from this that, contrary to the applicant’s assertions, OHIM did not deprive the earlier national registration of protection on German territory by adopting the contested decision and thus did not breach Article 6 quinquies of the Paris Convention.

26 Secondly, inasmuch as, by this plea, the applicant claims that OHIM has failed to grant registration of the trade mark sought pursuant to Article 6 quinquies (A)(1) of the Paris Convention, it should be noted, as has OHIM, that Article 6 quinquies (B)(ii) provides for the possibility of refusing registration where the trade mark sought is devoid of distinctive character. It follows that OHIM did not fail correctly to apply Article 6 quinquies (A)(1) of the Paris Convention by simply applying to registration of the trade mark sought the absolute ground of refusal laid down in Article 7(1)(b) of Regulation No 40/94, which precludes registration of signs devoid of distinctive character. Since the basis of the finding of the Board of Appeal of the lack of distinctive character of the trade mark sought is the subject of the fourth plea in law, there is no need to consider it in the context of the present plea.

27 Consequently, the second plea must be rejected.

The third plea in law, alleging breach of Article 73 of Regulation No 40/94, of Article 6 quinquies (A)(1) of the Paris Convention and of Article 2 of the TRIPs Agreement

Arguments of the parties

28 The applicant takes the view that OHIM failed sufficiently to examine the registration made earlier by the Deutsches Patent- und Markenamt, relating to a sign identical to that covered by the trade mark sought. It considers that the Community trade mark and national registrations are linked because of the possibility of claiming the latter’s seniority. The applicant concludes from this that OHIM must take into account earlier national registrations. In the alternative, it argues that it follows from the fact that the legal basis, constituted by First Council Directive 89/104/EEC of 21 December 1988 to approximate the laws of the Member States relating to trade marks (OJ 1989 L 40, p. 1) and by Regulation No 40/94, is the same that OHIM and the relevant national administration are to apply the same criteria laid down by the two texts and that, consequently, OHIM is to give reasons for applying those criteria differently from the national administration, that obligation flowing from Regulation No 40/94, the Paris Convention and the TRIPs Agreement.

29 OHIM submits that the references to the Paris Convention and the TRIPs Agreement are irrelevant, since those texts do not relate to the obligation to give reasons. It goes on to note that the reasons for a decision must state clearly and unequivocally the considerations on which the competent authority based its decision. According to OHIM, the contested decision complied with those requirements, since the Board of Appeal noted that the earlier national registration was not binding in the Community trade mark regime.

Findings of the Court

30 As a preliminary point, the references made by the applicant to the Paris Convention and the TRIPs Agreement must be disregarded. Unlike Regulation No 40/94, those two treaties do not lay down an obligation to give reasons for decisions and therefore are devoid of relevance in the context of the present case.

31 It is also appropriate to reject the applicant’s argument that the proprietor of a national mark may claim seniority thereof in relation to an application for a Community trade mark covering the same sign and identical goods or services. It is true, as the applicant stated, that, pursuant to Articles 34 and 35 of Regulation No 40/94, where the proprietor of a Community trade mark who has claimed seniority for an identical earlier national trade mark surrenders the earlier trade mark or allows it to lapse, he is to be deemed to continue to have the same rights as he would have had if the earlier trade mark had continued to be registered. However, those provisions cannot be intended to guarantee or have the effect of guaranteeing to the proprietor of a national mark registration thereof as a Community trade mark regardless of the existence of an absolute or relative ground of refusal.

32 Secondly, with regard to the alleged failure to examine the earlier German registration, it should be noted that the Community trade mark regime is an autonomous system with its own set of objectives and rules peculiar to it; it applies independently of any national system. Accordingly, the registrability of a sign as a Community trade mark is to be assessed on the basis of the relevant Community legislation alone, so that OHIM and, as the case may be, the Community Courts are not bound by a decision adopted in a Member State finding the same sign to be registrable as a national trade mark. That is the case even where such a decision was adopted by application of national legislation harmonised with Directive 89/104 (Case T‑106/00 Streamserve v OHIM(STREAMSERVE) [2002] ECR II‑723, paragraph 47).

33 Nevertheless, registrations already made in Member States are a factor which, without being decisive, may be taken into account for the purposes of registering a Community trade mark (Case T-122/99 Procter & Gamble v OHIM(Soap bar shape) [2000] ECR II-265, paragraph 61; Case T-24/00 Sunrider v OHIM(VITALITE) [2001] ECR II-449, paragraph 33; and Case T-337/99 Henkel v OHIM(Red and white round tablet) [2001] ECR II-2597, paragraph 58). Those registrations may thus provide analytical support for the assessment of an application for registration of a Community trade mark (Case T‑222/02 HERON Robotunits v OHIM (ROBOTUNITS) [2003] ECR II-4995, paragraph 52).

34 It is appropriate to note that the Board of Appeal held in paragraph 55 of the contested decision as follows:

‘… registration of the trade mark sought in the German trade mark register … has no binding power for the Community trade mark regime, which is an autonomous legal order independent of national trade mark regimes. In addition, registrations already made in Member States are a factor which, without being decisive, may merely be taken into account for the purposes of registering a Community trade mark. Furthermore, the registration documents submitted by the applicant do not indicate on the basis of which grounds registration of the sign was granted …’

35 Thus, the Board of Appeal duly took into account the existence of the national registration, without, even so, being in a position to examine the exact grounds which led the Deutsches Patent- und Markenamt to grant registration of the national trade mark. Since those grounds were not known to it, they could not be useful to it as analytical support.

36 Finally, with regard to the obligation to give reasons, the scope of which is set out in paragraph 18 above, it should be noted that paragraph 55 of the contested decision, cited in paragraph 34 above, explains in a clear and unequivocal manner the reasons which led the Board of Appeal not to follow the decision of the Deutsches Patent- und Markenamt. It should be added that that statement of reasons allowed, firstly, the applicant to be aware of the grounds of the contested decision in order to defend its rights, which is shown by the complaints submitted by the applicant in the second and third pleas in law in the present action, and, secondly, the Court to exercise its power of review of the legality of the contested decision.

37 It follows from the foregoing that the third plea in law must be rejected.

The fourth plea in law, alleging breach of Article 7(1)(b) of Regulation No 40/94

Arguments of the parties

38 The applicant takes the view that, in the present case, the trade mark sought has the minimum level of distinctiveness required by case-law. It notes in that regard that the overall impression created by the trade mark sought is characterised by the thin bottle neck, the bottle’s flattened and wide body, the greater part of which, seen from the front and the back, is bulbous, the lower part finished in a roll and depressions arranged symmetrically on the sides of the body of the bottle.

39 The applicant goes on to dispute OHIM’s observation that the trade mark sought constitutes a mere variation, minimal and limited, of typical shapes and that the mark has no additional feature which could be considered striking, individual or original. It notes that neither individuality nor originality is a criterion of a trade mark’s distinctiveness. On the contrary, a minimum level of distinctiveness is sufficient for the trade mark to be registrable. The applicant adds that there is no reason to apply a stricter criterion to assess the distinctive character of a three-dimensional trade mark.

40 The applicant also disputes the assertion that consumers, when making their choice, are guided by the label or the logo on the product and not by the shape of the bottle. It considers that, when making a purchase, consumers are guided by the shape of the bottle, and only after having identified the goods desired check their choice with the help of the label. It adds in that regard that the average consumer is quite capable of perceiving the shape of the packaging of the goods concerned as an indication of their commercial origin.

41 In the alternative, the applicant submits that there is no feature of the trade mark sought which is technical in function.

42 OHIM submits that consumers do not generally make a correlation between the shape or packaging of the goods and their origin, but to identify the commercial origin usually refer to the labels affixed to the package.

43 It adds that the features of the trade mark sought relied on by the applicant either constitute merely usual design features or would be perceived by the target consumer only after an analysis which that consumer will not undertake. It concludes that the trade mark sought will be perceived as a variant of the usual shape of packaging for the corresponding goods and not as an indication of their commercial origin.

44 Finally, OHIM notes that whether the design features, considered in isolation, fulfil technical or ergonomic functions is not important in the context of the assessment of distinctive character.

Findings of the Court

45 As a preliminary point, it should be recalled that the distinctive character of a mark must be assessed, firstly, in relation to the goods or services in respect of which registration is applied for and, secondly, in relation to the perception of it by the relevant public (Case T‑305/02 Nestlé Waters France v OHIM(Shape of a bottle) [2003] ECR II‑5207, paragraph 29, and Case T‑399/02 Eurocermex v OHIM(Shape of a beer bottle) [2004] ECR II‑1391, paragraph 19). The criteria for assessing the distinctive character of three-dimensional marks consisting of the shape of a product are no different from those applicable to other categories of trade mark (Case T‑305/02, paragraph 35, and Case T‑399/02, paragraph 22). Moreover, in the context of the assessment of the distinctive character of a trade mark, the overall impression produced by that trade mark must be analysed (T‑305/02, paragraph 39, and the case-law cited).

46 In the present case, the goods covered by the trade mark sought are foods for everyday consumption. Consequently, the relevant public is all consumers. Accordingly, the distinctive character of the trade mark sought should be assessed taking account of the presumed expectation of the average consumer, who is reasonably well-informed and reasonably observant and circumspect (Case T‑305/02, paragraph 33, and Case T‑399/02, paragraphs 19 and 20).

47 Firstly, with regard to the applicant’s suggestion that, in the case of goods such as those at issue, consumers make their choice on the basis of the shape of the packaging rather than with the help of the label, it may be observed that average consumers are not in the habit of making assumptions about the origin of products on the basis of their shape or the shape of their packaging in the absence of any graphic or word element (Case C‑136/02 P Mag Instrument v OHIM [2004] ECR I‑9165, paragraph 30, and the case-law cited). Likewise, consumers first see the bottles in which such goods are contained as a means of packaging (Joined Cases T‑146/02 to T‑153/02 Deutsche SiSi-Werke v OHIM(Stand-up pouches) [2004] ECR II‑447, paragraph 38). Since the applicant supplied no evidence to show why that case-law should not be applied to the present case, its suggestion must be rejected.

48 It should be added that OHIM’s disputed conclusion is not incompatible with the circumstance, raised by the applicant, that the average consumer is quite capable of perceiving the shape of the packaging of goods for everyday consumption as an indication of their commercial origin (Case T‑305/02, paragraph 34). Even if that is the case, that general conclusion does not mean that all packaging of such goods has the distinctive character required for registration as a Community trade mark. Whether a sign has distinctive character must be assessed in each specific case in the light of the criteria set out in paragraphs 45 and 46 above.

49 Secondly, with regard to the four features which, according to the applicant, contribute to the bottle’s distinctiveness, it should be noted at the outset that the mere fact that that shape is a variant of a common shape of a given type of product is not sufficient to establish that the mark is not devoid of any distinctive character. It must in any case be determined whether such a mark permits the average consumer, who is reasonably well informed and reasonably observant and circumspect, to distinguish the product concerned from those of other undertakings without conducting an analytical examination and without paying particular attention (Mag Instrument v OHIM, paragraph 32). The more closely the shape for which registration is sought resembles the shape most likely to be taken by the product in question, the greater the likelihood of the shape being devoid of any distinctive character (Mag Instrument v OHIM, paragraph 31).

50 With regard to the stretched neck and the flattened body, it is clear that the parameters of the trade mark sought do not depart from the usual shape of a bottle containing goods such as those covered by the trade mark sought. Neither the length of the neck and its diameter nor the proportion between the width and thickness of the bottle is in any way individual.

51 The same conclusion applies to the roll. That is a usual design feature of bottles marketed in the sector concerned.

52 The only characteristic in which the trade mark sought differs from the usual shape is constituted by the lateral hollows. Unlike the examples supplied by OHIM, the trade mark sought has tight curves, almost giving the appearance of semicircles.

53 However, even if that feature could be considered unusual, alone it is not sufficient to influence the overall impression given by the trade mark sought to such an extent that it departs significantly from the norm or customs of the sector and thereby fulfils its essential function of indicating origin (Mag Instrument v OHIM, paragraph 31).

54 Taken as a whole, therefore, the above four features do not create an overall impression which might serve to challenge that finding. It follows that, assessed by reference to the overall impression which it gives, the trade mark sought is devoid of distinctive character.

55 That conclusion is not incompatible with the circumstance, put forward by the applicant, that neither individuality nor originality is a criterion for distinctiveness of a trade mark. Even if the existence of individual or original features does not constitute a condition sine qua non for registration, their presence, on the contrary, may nevertheless confer the degree of distinctive character required on a trade mark which would otherwise be devoid of distinctive character. That is why, after having assessed the impression given by the bottle and held in paragraph 45 of the contested decision that ‘the client will not obtain from the bottle itself, as it is, any indication of commercial origin’, the Board of Appeal considered whether the trade mark sought had specific features which conferred on it the required minimum distinctiveness. Having held in paragraph 49 of the contested decision that such was not the case, it correctly concluded that the trade mark sought was devoid of distinctive character.

56 Thirdly, with regard to the circumstance put forward by the applicant that the features characterising the trade mark sought have no technical or ergonomic function, it should be noted that, even if that were proven, it cannot affect the lack of distinctiveness of the trade mark sought. In so far as the relevant public perceives the sign as an indication of the commercial origin of the goods or services, whether or not it serves simultaneously a purpose other than that of indicating commercial origin, for example a technical purpose, is unrelated to its distinctiveness (see, to that effect, Case T‑173/00 KWS Saat v OHIM (Shade of orange) [2002] ECR‑3843, paragraph 30).

57 It follows that the fourth plea in law must also be rejected, and therefore the action dismissed.

Costs

58 Under Article 87(2) of the Rules of Procedure of the Court of First Instance, the unsuccessful party is to be ordered to pay the costs if they have been applied for in the successful party’s pleadings. Since the applicant has been unsuccessful, it must be ordered to pay the costs, in accordance with the form of order sought by OHIM.

On those grounds,

THE COURT OF FIRST INSTANCE (Second Chamber)

hereby:

1. Dismisses the action;

2. Orders the applicant to pay the costs.

Delivered in open court in Luxembourg on 15 March 2006.