OPINION OF ADVOCATE GENERAL

SHARPSTON

delivered on 21 May 2015 (1)

Case C‑569/13

Bricmate AB

v

Tullverket

(Request for a preliminary ruling from the Förvaltningsrätten i Malmö (Sweden))

(Validity of Council Implementing Regulation No 917/2011 imposing a definitive anti-dumping duty and collecting definitively the provisional duty imposed on imports of ceramic tiles originating in the People’s Republic of China)

1. In 2011, the Council of the European Union imposed an anti-dumping duty on imports of ceramic tiles originating in the People’s Republic of China (‘China’). A Swedish importer of such tiles has challenged the levying of that duty on its imports. It alleges that the regulation imposing the duty is vitiated by errors of fact and assessment and by failures on the part of the European Commission to conduct the investigation procedure correctly, in particular to take account of certain specific submissions made by the importer. The dispute is now before the Förvaltningsrätten i Malmö (Administrative Court, Malmö) which seeks a preliminary ruling on the validity of the regulation in issue.

2. Other issues concerning a different challenge to the same regulation have been referred to the Court in Case C‑687/13 Fliesen-Zentrum Deutschland, in which I also deliver my Opinion today.

Legislative and procedural background

3. The rules governing the imposition of anti-dumping duties are contained in Regulation No 1225/2009 (‘the basic regulation’). (2) The anti-dumping duty in issue in the main proceedings was first imposed by Regulation No 258/2011 (‘the provisional regulation’) (3) and then confirmed, with adjustments, by Regulation No 917/2011 (‘the definitive regulation’ or ‘the contested regulation’). (4)

The basic regulation

4. Article 1(1) of the basic regulation sets out the principle that an anti-dumping duty may be applied to any dumped product whose release for free circulation in the European Union causes injury. Article 1(2) defines a dumped product as one whose export price to the Union is less than a comparable price for the like product, in the ordinary course of trade, as established for the exporting country.

5. Article 2 lays down the principles and rules governing determination of dumping. Essentially, for a given product exported from a third country, a normal value on the domestic market and an export price to the Union are established, and a fair comparison is made between the two, taking account of various factors which might influence differences between them. If a comparison of weighted averages shows that the normal value exceeds the export price, the amount by which it does so is the dumping margin.

6. Article 3 (‘Determination of injury’) provides, in particular:

‘...

2. A determination of injury shall be based on positive evidence and shall involve an objective examination of both:

(a) the volume of the dumped imports and the effect of the dumped imports on prices in the [Union] market for like products; and

(b) the consequent impact of those imports on the [Union] industry.

3. With regard to the volume of the dumped imports, consideration shall be given to whether there has been a significant increase in dumped imports, either in absolute terms or relative to production or consumption in the [Union]. With regard to the effect of the dumped imports on prices, consideration shall be given to whether there has been significant price undercutting by the dumped imports as compared with the price of a like product of the [Union] industry, or whether the effect of such imports is otherwise to depress prices to a significant degree or prevent price increases, which would otherwise have occurred, to a significant degree. No one or more of these factors can necessarily give decisive guidance.

…

5. The examination of the impact of the dumped imports on the [Union] industry concerned shall include an evaluation of all relevant economic factors and indices having a bearing on the state of the industry, including the fact that an industry is still in the process of recovering from the effects of past dumping or subsidisation, the magnitude of the actual margin of dumping, actual and potential decline in sales, profits, output, market share, productivity, return on investments, utilisation of capacity; factors affecting [Union] prices; actual and potential negative effects on cash flow, inventories, employment, wages, growth, ability to raise capital or investments. This list is not exhaustive, nor can any one or more of these factors necessarily give decisive guidance.

6. It must be demonstrated, from all the relevant evidence presented in relation to paragraph 2, that the dumped imports are causing injury within the meaning of this Regulation. Specifically, this shall entail a demonstration that the volume and/or price levels identified pursuant to paragraph 3 are responsible for an impact on the [Union] industry as provided for in paragraph 5, and that this impact exists to a degree which enables it to be classified as material.

…’

7. Article 17 of the basic regulation concerns sampling. In particular, where the number of complainants, exporters or importers, types of product or transactions is large, the investigation may be limited to a reasonable number of parties, products or transactions by using samples which are statistically valid on the basis of information available at the time of the selection (Article 17(1)). Preference is to be given to choosing a sample in consultation with, and with the consent of, the parties concerned, provided such parties make themselves known and make sufficient information available (Article 17(2)).

8. Article 20 is entitled ‘Disclosure’. Article 20(1) provides:

‘The complainants, importers and exporters and their representative associations, and representatives of the exporting country, may request disclosure of the details underlying the essential facts and considerations on the basis of which provisional measures have been imposed. Requests for such disclosure shall be made in writing immediately following the imposition of provisional measures, and the disclosure shall be made in writing as soon as possible thereafter.’

The anti-dumping proceeding and the provisional regulation

9. The Commission gave notice of the initiation of an anti-dumping proceeding concerning imports of ceramic tiles originating in China on 19 June 2010. (5) The investigation of dumping and injury covered the period from 1 April 2009 to 31 March 2010 (the ‘investigation period’ or ‘IP’). Examination of trends for the purposes of assessing injury and causation covered the period from 1 January 2007 to 31 March 2010.

10. Bricmate AB (‘Bricmate’) responded to the request in the notice for interested parties to make themselves known and was selected by the Commission to participate in the investigation, in a sample of seven unrelated importers (independent importers having no link to any particular exporter). Bricmate responded to the questionnaire sent to it on 10 September 2010. It stated, inter alia, that the tiles which it imported from China were of a particularly high quality, even though they bore the same product control numbers (‘PCNs’) as inferior tiles, with which they could not be compared, and that certain of them came in dimensions, or were produced using cutting techniques, which were not available from Union producers.

11. On 16 March 2011, the Commission adopted the provisional regulation, Article 1(1) of which imposed a provisional anti-dumping duty on imports of ‘glazed and unglazed ceramic flags and paving, hearth or wall tiles; glazed and unglazed ceramic mosaic cubes and the like, whether or not on a backing, currently falling within CN codes 6907 10 00, 6907 90 20, 6907 90 80, (6) 6908 10 00, 6908 90 11, 6908 90 20, 6908 90 31, 6908 90 51, 6908 90 91, 6908 90 93 and 6908 90 99, and originating in [China]’.

12. Under Article 1(2), the rate of the provisional anti-dumping duty applicable to the net, free-at-Union-frontier price, before duty, of the products in question manufactured by certain listed companies varied between 26.2% and 36.6%, with a rate of 73.0% being applied to those produced by all other companies.

13. Recitals 27 to 32 in the provisional regulation, under the heading ‘Like product’, read as follows:

‘(27) One party claimed that the product imported from China and that produced by the Union industry were not comparable.

(28) It is recalled that the Commission based the price comparisons on product types distinguished on the basis of product control numbers (“PCN”) based on eight characteristics.

(29) The party in question presented its arguments during a hearing before the Hearing Officer. According to the arguments the lack of comparability was due to different technology, material, polishing and design used for production of Union and Chinese tiles. Technologically advanced lines produced high quality tiles with screen printing and several colours. The company explained that there were different printing technologies for screen printing, roto-printing and inkjet printing.

(30) Despite requests for detailed submission elaborating on all these aspects of product comparability, the party failed to substantiate its claims. Also the argument on improving the comparability has not been supported by any evidence. Further, the party itself acknowledged that the product types that would be covered by adding the four suggested criteria, would represent only 0.5% of the tiles’ market. As stated in the report produced by the Hearing Officer, which summarised the position of the company concerned, the remaining 99.5% products falling under the same PCNs were similar.

(31) As mentioned above the party did not substantiate the need to introduce the additional criteria nor their potential impact on prices. Hence, in view of the negligible market share of the product types concerned and the explicit acknowledgment by the party that 99.5% of the tiles were comparable under the PCN concerned, the claim to add additional criteria to the PCN structure had to be provisionally rejected.

(32) It is concluded that the product concerned, the product produced and sold on the domestic market of China and on the domestic market of the USA, which served provisionally as the analogue country, as well as the product manufactured and sold in the Union by the Union producers were found to have the same basic physical and technical characteristics as well as the same basic uses. They are therefore provisionally considered as alike within the meaning of Article 1(4) of the basic Regulation.’

14. Recitals 68 to 111 in the provisional regulation analysed the injury to the Union industry, concluding that it had suffered material injury within the meaning of Article 3(5) of the basic regulation.

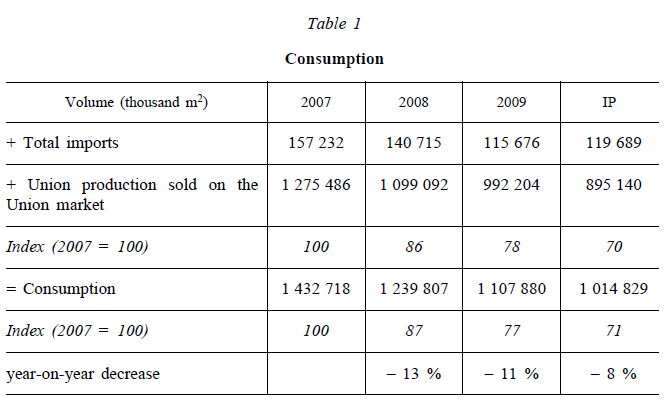

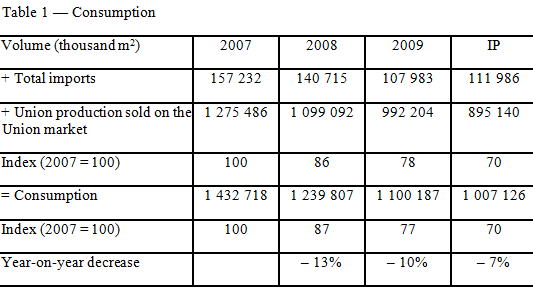

15. According to recitals 71 and 72, over the period from 2007 and the investigation period, Union consumption decreased by 29%, in particular (by 13%), between 2007 and 2008 and (by 8% as compared to 2009) in the investigation period. Union consumption was established by adding the volume of imports (based on Eurostat data) and the volume of sales by Union producers on the Union market (based on verified data provided by national and European associations of producers). There followed Table 1:

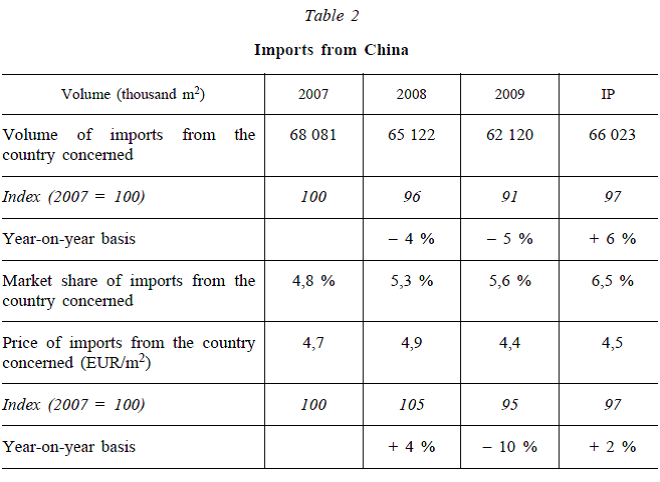

16. In recital 73, the Commission stated:

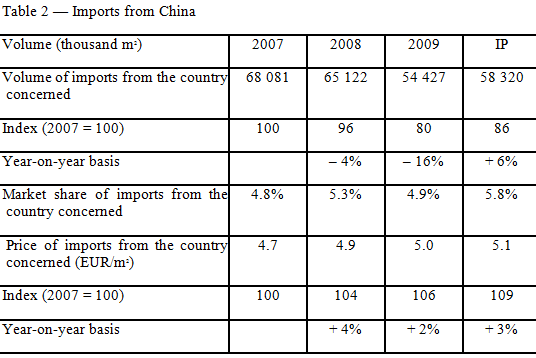

‘The volume, market share and average prices of imports from China developed as set out below. The following quantity and price trends are based on Eurostat data.’

There followed Table 2:

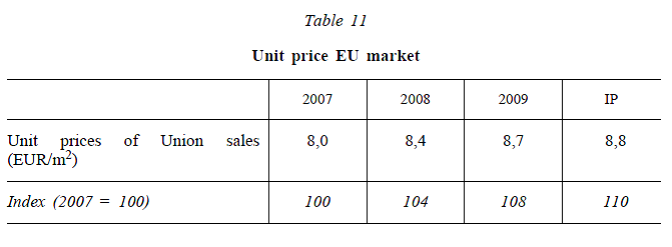

17. Table 11 in recital 96 showed the evolution of unit sales prices of the Union industry:

18. On the basis of, inter alia, those figures, the Commission analysed the causation of the material injury in recitals 112 to 136. Recitals 113 to 116, under the heading ‘Impact of the imports from China’, read as follows:

‘(113) The increasing market share of Chinese exporting producers over the period considered coincided in time with a decrease of the Union industry’s profits and a substantial increase of its stocks.

(114) This also coincided with a decrease in Union consumption. However, while the Chinese imports decreased in volume by 9 percentage points between 2007 and 2009, in line with the shrinking consumption (although not at the same pace — consumption shrank by 23 percentage points over the same period), since 2007 the Chinese market share was steadily growing. Moreover, between 2009 and the IP, despite further decrease in consumption by 6 percentage points, Chinese imports increased by 6 percentage points.

(115) The price differential (based on Eurostat average figures) between Chinese imports and the prices of the Union industry was very significant during the whole period considered. The fact that already in 2007 it amounted to over 40% suggests that the price strategy by the Chinese exporting producers started before the economic crisis. Also, this differential increased post-crisis reaching 50% in the IP.

(116) The increasing market share of the Chinese imports combined with decreasing prices and the increasing price differential between Union and Chinese prices coincided in time with the deterioration of the situation of the Union industry.’

19. In recitals 117 to 134, the Commission examined other possible causes of the injury, concluding, at recitals 135 and 136:

‘(135) It was thus concluded that there is a causal link between the injury suffered by the Union industry and the dumped imports from China. The economic crisis and imports from third countries other than China had an impact on the situation of the Union industry but it was not such as to break the causal link established between the dumped imports from China and the material injury suffered by the Union industry.

(136) Based on the above analysis of the effects of all known factors on the situation of the Union industry, it was therefore provisionally concluded that there is a causal link between the dumped imports from China and the material injury suffered by the Union industry during the IP.’

20. Under the heading ‘Interests of importers’, the Commission stated, inter alia:

‘(144) … the investigation revealed that it is possible for importers and users to switch to products sourced from third countries or from within the Union. This change can occur quite easily since the product under investigation is manufactured in several countries, both in the Union and outside (Turkey, United Arab Emirates, Egypt, Brazil, countries of South-East Asia, and others).

(145) One importer declared that it tried to switch suppliers, as a consequence of the initiation of the investigation, but its efforts were unsuccessful. On the other hand, another importer declared that this process was already ongoing at the time of the investigation and was successful. A third one claimed that it would expand its portfolio to non-Chinese producers and that this would be easily done.

(146) It is therefore provisionally concluded that the imposition of measures would not hamper Union importers from buying similar products from other sources. Further, the aim of the anti-dumping duties is not to seal off specific trade channels but to restore the level playing field and counter-act unfair trade practices.’

Procedural developments

21. On 15 April 2011, Bricmate gave the Commission its response to the provisional regulation, complaining that the Commission had failed to exercise due care, to respect Bricmate’s rights of defence and to comply with its duty to state reasons, in particular by failing to respond to Bricmate’s observations concerning price trends, product comparability and the availability of similar products on the Union market.

22. On 1 July 2011, the Commission sent Bricmate a general disclosure document (essentially a draft definitive regulation) on the basis of which it proposed to recommend that the Council impose definitive anti-dumping measures. Point 77 of that document stated: ‘As concerns the disparities in the statistics noted by the interested parties concerned it was considered that these were of minor magnitude with no significant impact on the overall determinations made. It is therefore neither necessary, nor meaningful to amend the data used.’

23. On the same date, the Commission replied to Bricmate’s comments of 15 April 2011, dismissing its complaints. In particular, it assured Bricmate that its views had been taken into account and stated:

‘Lack of product comparability between China and the Union. Products manufactured in China cannot be found elsewhere. Small importers will not be able to purchase them.

Reply: in the provisional regulation (recitals 27-32), the Commission concluded that the products manufactured in China were comparable to those produced in the Union. The submission of your client was also taken into consideration. On this issue, we recall what [was] already observed in recitals 144-145 of the provisional Regulation, i.e. that the product concerned is manufactured in a very large number of non-dumping countries. The Commission has not received any evidence proving that there would be a wide supply shortage in case of imposition of measures on ceramic tiles from China.’

24. Bricmate submitted further observations on 11 July 2011, again complaining that its submissions had not been taken into account. On 15 July 2011, it supplemented those observations with a claim that Eurostat figures showed an increase rather than a decrease in average prices for imports of ceramic tiles from China.

25. By letter of 27 July 2011, the Commission replied to Bricmate’s observations, again rejecting Bricmate’s complaints. In particular, it stated that recital 145 in the provisional regulation referred specifically to Bricmate. Bricmate responded on 23 August 2011, maintaining its complaints and accusing the Commission of ‘cherry-picking’ data.

26. During that procedural stage, two other entities (ENMON GmbH, a German importer, and the Foreign Trade Association, a European association of economic operators) — but not Bricmate — made submissions to the Commission pointing out, inter alia, that certain of the Eurostat statistics used in the provisional regulation, concerning volumes and prices of imports from China, appeared implausible. ENMON drew attention in particular to discrepancies relating to imports into Spain in 2009.

The definitive regulation

27. On 12 September 2011 the Council adopted the definitive regulation, Article 1(1) of which imposed a definitive anti-dumping duty on imports of the same products as the provisional regulation.

28. Under Article 1(2), the rate of the definitive duty varied between 26.3% and 36.5% for products manufactured by the listed companies, with a rate of 69.7% being applied to those of all other companies.

29. Determination of injury is examined at recitals 99 to 137, examining and dismissing many of the objections to the analysis and conclusions in the provisional regulation. In particular, at recital 108, the Council stated:

‘As for the evolution of Chinese prices, the average import prices indicated in recital 73 of the provisional Regulation were based on Eurostat statistics. Questions have been raised as concerns the accuracy of the average import prices to certain Member States but no changes to official statistics have been confirmed. In any event, it is recalled that the Eurostat data was used only to establish the general trends and that even if the Chinese import prices were to be adjusted upwards, the injury picture as a whole would still remain the same with high margins for undercutting and underselling. In this context it should be noted that for the calculation of both injury and dumping margins Eurostat data was not used. Only verified data from visited companies have been used in order to determine the level of the margins. Therefore, even if the discrepancies to the statistics were to be found, this would not have any impact on the level of the margins disclosed.’

30. Causation is examined in a similar way at recitals 138 to 169, concluding in the latter recital:

‘None of the arguments submitted by the interested parties demonstrates that the impact of factors other than dumped imports from China is such as to break the causal link between the dumped imports and the injury found. The conclusions on causation in the provisional Regulation are hereby confirmed.’

31. The section headed ‘Interest of importers’ contains the following recitals:

‘[…]

(173) Following final disclosure two parties opposed the conclusion that importers can easily switch from Chinese supplies to other sources of supply, in particular because qualities and prices were not comparable.

(174) Regarding this claim, it is recalled that a large part of imports is not affected by duties as it is of non-Chinese origin. The characteristics of the product, being produced all over the world in comparable qualities, suggest that these products are interchangeable and that therefore a number of alternative sources are available, despite the allegations made. Even for importers that rely on Chinese imports, which the investigation found to be dumped and sold at prices which significantly undercut those of the products originating in the Union, the investigation found that importers can apply to their selling prices mark-ups in excess of 30%. This, together with the fact that importers have been found to have realised profits of around 5% and their possibility to pass on at least part of potential cost increases to their customers, suggests that they are in a position to cope with the impact of measures.

(175) Furthermore, and as concluded in recital 144 of the provisional Regulation, the imposition of measures would not hamper Union importers from increasing their import shares of products from the other non-dumped sources available to them both in the Union and in other third countries.

[…]’

32. On 15 September 2011, the Commission sent Bricmate a final letter replying to its observations of 23 August 2011 and again rejecting its complaints.

Proceedings before the General Court

33. Bricmate’s action for annulment of the definitive regulation, lodged at the Registry of the General Court on 24 November 2011, was dismissed as inadmissible on 21 January 2014, on the ground that the applicant was not individually concerned by the definitive regulation and that the definitive regulation entailed implementing measures which could be challenged before the national authorities. (7)

National proceedings, questions referred and procedure before the Court of Justice

34. Following the adoption of the definitive regulation, Tullverket (the Swedish Customs Service) imposed anti-dumping duties on Bricmate’s imports of ceramic tiles from China, at the rates specified for the products of the relevant Chinese exporters. Bricmate brought proceedings before the Förvaltningsrätten i Malmö, challenging 32 assessments made by Tullverket between 31 October 2011 and 28 May 2012. In those proceedings, Bricmate put forward two pleas in law, the first being divided in two parts. (For the substance of those pleas, see below, point 37 and my subsequent assessment of the question referred.)

35. The court seised found that it could not dismiss Bricmate’s arguments as obviously unfounded. In order to decide whether the anti-dumping duties imposed by Tullverket should be cancelled, it was necessary to know whether the definitive regulation was valid. That was a matter on which only the Court of Justice could rule, so a preliminary ruling must be requested. The national court was, moreover, aware that Bricmate had brought an action before the General Court, whose admissibility had been challenged by the Council and the Commission. Bearing in mind, therefore, the need to ensure an effective examination of the matter and to secure Bricmate’s right to effective judicial protection, the Förvaltningsrätten i Malmö has requested a preliminary ruling on the following question:

‘Is [the definitive regulation] invalid on any one of the following grounds:

1. that the investigation of the EU institutions contains manifest errors of fact,

2. that the investigation of the EU institutions contains manifest errors of assessment,

3. that the Commission has failed in its obligation to exercise due care and has disregarded Article 3(2) and (6) of [the basic regulation],

4. that the Commission has disregarded its obligations under Article 20(1) of [the basic regulation] and has disregarded the company’s rights of defence,

5. that the Commission, contrary to Article 17 of [the basic regulation], has failed to take into account the information which the company supplied, and/or

6. that the Commission failed in its duty to state reasons (pursuant to Article 296 [TFEU])?’

36. Written observations have been submitted by Bricmate, the Council and the Commission, all of whom presented oral argument at the hearing on 3 December 2014.

37. All those submissions have addressed the question referred on the basis of Bricmate’s pleas in law in the main proceedings. In that light, points 1 and 2 of the question correspond to the first part of the first plea; point 3 to the second part of that plea; and points 4 to 6 to the second plea in law. I shall take the same approach in my assessment.

Assessment

First part of the first plea in the main proceedings (manifest error of fact and manifest error of assessment; points 1 and 2 of the question referred)

Statistics

38. Underlying Bricmate’s arguments on the validity of the contested regulation are two apparent errors in the figures used.

39. First, Bricmate asserts, and the Commission has confirmed in its written submissions, that the figure of 66 023 000 m² for Union imports from China (8) during the investigation period was overstated. The Commission states that it should have been 64 821 000 m²; Bricmate claims that it should have been 58 176 269 m², although I can find no specific evidence in the case-file to support that figure.

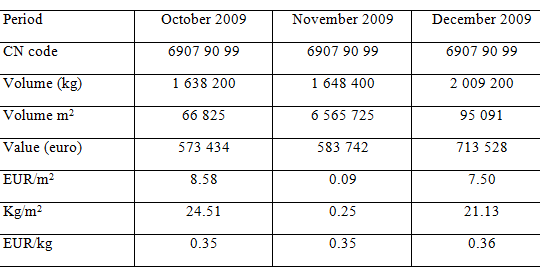

40. However, Bricmate points to a further discrepancy in the figures for imports of ceramic tiles under CN code 6907 90 99 (9) from China into Spain in November 2009, affecting prices and volumes for the calendar year 2009 and for the investigation period.

41. Eurostat’s original figures for the last quarter of 2009, nearly identical to those provided by the Spanish authorities, were as follows:

42. Based on (inter alia) those figures, Eurostat’s data showed imports of 10 378 191 m² of ceramic tiles (all CN codes) from China into Spain in 2009 (10 698 368 m² for the investigation period) at a price of EUR 24 891 014 (EUR 27 658 131 for the investigation period), amounting to EUR 2.40/m² (EUR 2.59/m² for the investigation period, rounded to the nearest cent in both cases).

43. In correspondence with Bricmate in October and November 2011 the Spanish authorities acknowledged that there was an error, but stated that it could not be officially corrected at that late stage. The institutions have stated that neither the Commission nor Eurostat (which is part of the Commission) could amend the figures without an official correction from the Spanish authorities. However, in its written submissions the Commission refers to a statement by Eurostat dated 27 January 2014 indicating that the correct figures for CN code 6907 90 99 were 881 773.77 m² (10) instead of 7 372 603.49 m² for the calendar year 2009 and 64 940.30 m² instead of 6 565 771.02 m² (11) for the month of November.

44. Given the clear acknowledgments in the Commission’s written submissions, I shall proceed on the basis that the figures which Bricmate asserts to be incorrect were indeed incorrect. As regards the first error (imports under CN code 6908 90 99 for the Union as a whole), I accept the Commission’s corrected figure, and I shall assume it to apply to imports both for 2009 and for the investigation period. As regards the second error (imports under CN code 6907 90 99 into Spain for November 2009), I accept the corrected figure given by Eurostat in January 2014, falling within both the calendar year 2009 and the investigation period. On that basis, the figures in Tables 1 and 2 in the provisional regulation (12) need to be amended.

45. I have therefore recalculated those figures. In my calculations, I have deducted in each table:

– first, 1 202 000 m² from the volume of imports for each of the two periods concerned, that being the correction accepted by the Commission in respect of the first error; and

– second, 6 490 830 m² from the volume of imports for 2009, and 6 500 831 m² from the volume for the investigation period, those being the amounts overstated in the second error for, respectively, the calendar year 2009 and November 2009, according to a comparison of the different figures in the Eurostat statement of 27 January 2014.

46. Consequently, I have deducted a total of 7 692 830m² from the volume of imports for 2009 and 7 702 831m² from the volume for the investigation period.

47. I have adjusted figures in Table 2, derived from the import figures, in consequence.

48. For the market share of imports from China, I have calculated the percentage of the corrected total consumption in Table 1 which is accounted for by imports from China.

49. I have calculated the price per square metre of imports from China as follows. First, since Bricmate has not challenged the total cost of imports during the periods considered, I have established that total cost by multiplying the price per square metre in Table 2 by the volume of imports originally given in the provisional regulation. I have then divided that total cost by the corrected volume of imports to reach a corrected price per square metre.

50. Finally, I have rectified what appears to have been an error in the index for the evolution of prices between 2007 and 2008 (104, rather than 105).

51. The revised tables, using the same format (13) and the same degree of rounding as in the originals, are as follows:

Submissions

52. Bricmate argues that the conclusions of the definitive regulation were based on manifest errors of fact (the statistical errors) leading to a manifest error of assessment. Using the figures adjusted according to its calculations, (14) it submits in the main proceedings that:

(i) the volume of imports from China to the Union fell by 15%, not 3% (recitals 73 and 74 in the preamble to the provisional regulation);

(ii) Union consumption fell by 30%, not 29% (recital 72), which had a significant effect on the calculation of market shares;

(iii) the market share of Chinese imports increased by 1%, not 1.7%, and never reached 6%; there was a fall in market share between 2008 and 2009, not steady growth over the whole period (recitals 73 and 74);

(iv) the market share of the Union industry did not fall during the investigation period (recital 87) but remained stable at 89%;

(v) the price of Chinese imports did not fall by 3% between 2007 and the investigation period (Table 2 in recital 73) but rose steadily, by 10% overall;

(vi) the price differential between Chinese imports and the Union industry did not increase from 40% to 50% (recital 115) but remained stable throughout the period at 42%.

Bricmate also takes issue with the alleged correlation between an increase in the Chinese exporters’ market share and a decrease in the Union industry’s profits (recital 113 in the provisional regulation), which it considers to be a manifest error of assessment. It stresses that:

(vii) between 2008 and 2009, the Union industry’s profit margin fell (on the Commission’s figures in Table 12 in the provisional regulation, which Bricmate does not dispute) from +0.6% to ‑1.2% while (on the adjusted figures) the market share of Chinese imports fell from 5.3% to 4.9%;

(viii) between 2009 and the end of the investigation period, the Union industry’s profit margin recovered (again on the Commission’s figures) to +0.4% and the market share of Chinese imports increased (on the adjusted figures) to 5.8%;

(ix) between 2007 and 2009, while Union consumption fell by 23%, the volume of Chinese imports did not fall by 9% (recital 114 in the provisional regulation) but (on the adjusted figures) by 20%, commensurately with the fall in consumption.

53. In addition to those errors, Bricmate considers that the assertion in recital 108 to the definitive regulation (that ‘even if the Chinese import prices were to be adjusted upwards, the injury picture as a whole would still remain the same with high margins for undercutting and underselling’) is a manifest error of assessment for three reasons:

(i) the error in import volumes in the Eurostat statistics affected not only the average price of Chinese imports but also a number of other economic factors;

(ii) the injury picture (and thus the causal link) had changed;

(iii) any injury caused by price undercutting must be assessed together with the price trend; an assessment relating to injury and causation requires an analysis of the relevant factors over time, not simply a static picture of the situation during the investigation period. (15)

54. If the Council had had the correct figures at its disposal, Bricmate considers, it could not have concluded that imports from China were a significant cause of the injury complained of by the Union industry.

55. The Council points out that Bricmate did not raise any issue as to the accuracy of the Eurostat data until its response to the general disclosure document on 15 July 2011 (as regards the first error) or until the national court proceedings (as regards the discrepancy in the figures for Spain). Other importers did raise the first point but did not identify the relevant CN code sufficiently for the alleged error to be addressed. As regards the discrepancy in the figures for Spain in November 2009, the institutions were required to take the official Eurostat data as their basis; those data were not amended because Eurostat relies on data collected by national bodies and the Spanish data were not amended, the first official confirmation of an error having been made after the adoption of the definitive regulation.

56. However, even if Bricmate’s data were used, the conclusions would be no different. First, the assessment is based on a range of different indicators, none of which can be decisive (Article 3(3) and (5) of the basic regulation). When all those indicators are taken together, the result is still clear, even if less pronounced when the Eurostat figures are adjusted: high margins of price undercutting are still found; most of the injury factors and macroeconomic indicators are unaffected, as are the verified microeconomic data from the sampled Union producers; and the evaluation of injury and dumping margins was not based on Eurostat data. In any event, the adjustments to the Eurostat data are either insignificant or do not affect the conclusions concerning market share or price differentials. Moreover, the institutions carried out a dynamic assessment of all injury factors over the whole of the period concerned.

57. The Commission accepts that the import figures referred to by Bricmate were incorrect, but submits that they were not obviously so at the time of the adoption of the provisional regulation and the definitive regulation, so that there could be no question of a manifest error of assessment. Like the Council, it submits that the assessments were based on a wide range of factors, not only the Eurostat data, and that the conclusions would have been no different even if those data had been adjusted.

Assessment

58. To the extent that the definitive regulation was based on incorrect data, it was based on errors of fact. Bricmate considers that those errors of fact were both serious and manifest, giving rise to manifest errors of assessment affecting, in part, the conclusions on the injury to the Union industry and, principally, the conclusions on the causal link between the imports from China and that injury, and that the two types of error, taken together, constitute grounds for declaring the contested regulation invalid.

59. According to settled case-law, the institutions of the Union enjoy a broad discretion in the field of, in particular, anti-dumping measures, by reason of the complexity of the economic, political and legal situations which they have to examine. ‘The judicial review of such an appraisal must therefore be limited to verifying whether the procedural rules have been complied with, whether the facts on which the contested choice is based have been accurately stated, and whether there has been a manifest error in the appraisal of those facts or a misuse of powers.’ (16)

60. However, the present aspect of the case does not involve any issue of non-compliance with procedural rules, and there is no suggestion of any misuse of powers. The inaccuracy of certain facts is acknowledged. The alleged errors of assessment all follow from that inaccuracy, not from an erroneous appraisal of facts which were originally stated accurately.

61. In that context, I take the view that the mere existence of factual errors — however manifest — should not on its own entail the automatic invalidity of an anti-dumping regulation. What matters is not the obviousness of the errors but whether they were such as to render it uncertain that the Council would have reached the same conclusions if it had had the correct figures at its disposal. (17)

62. None the less, I note that the erroneous figures for imports into Spain show the volume in square metres for November 2009 as nearly 100 times greater than those for October and nearly 70 times greater than those for December, although the volume in kilogrammes and the value in euros remain more or less constant over the same period. Moreover, the figures for volume in kilogrammes and value in euros are coherent over the three months, and those for volume in square metres are coherent as between October and December. It should therefore, I consider, have been obvious to anyone looking at those figures that there was a strong likelihood of an error and that verification was needed. In that regard, the Commission explained at the hearing that the anomaly was not apparent until the monthly figures for imports into Spain under each CN code were seen, that the department investigating the dumping did not obtain such detailed figures until alerted to the discrepancy at a late stage in the investigation, and that having obtained them it checked to see whether they changed the analysis in any way, as is stated in recital 108 to the definitive regulation.

63. In those circumstances, I do not think that the Commission should be overly criticised for having failed to identify the error earlier.

64. Another aspect of the argument which I consider irrelevant is the fact that Bricmate did not raise the most significant statistical errors until the anti-dumping investigation had been terminated. This is a request by a national court for a preliminary ruling, and the only question is whether the contested regulation is in fact vitiated by any defect. There is no procedural requirement that such a defect should have been brought to the institutions’ notice within a particular time-limit.

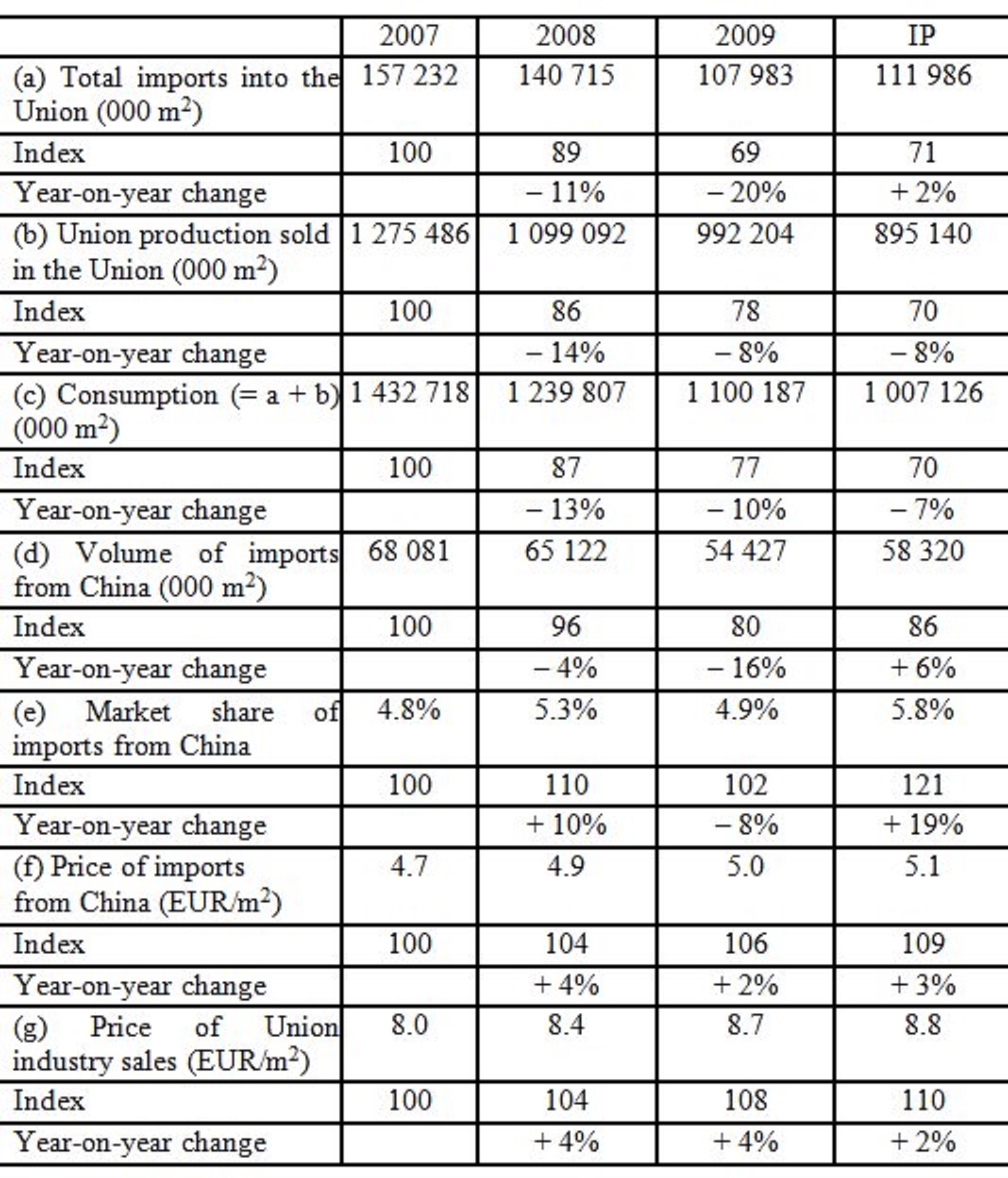

65. I turn, therefore, to the nub of the question: to what extent is it likely that use of the correct figures would have affected the assessment of dumping? To answer that question, I find it useful to set out the relevant figures from Tables 1, 2 and 11 in the provisional regulation (including both undisputed and corrected figures) in a single table, adding certain ‘index’ and ‘year-on-year change’ rows for ease of comparison, the index always taking as its starting point the value of 100 for the calendar year 2007 (although, when reading the expression ‘year-on-year change’, the caveat remains that the calendar year 2009 and the investigation period — 1 April 2009 to 31 March 2010 — overlap to a considerable extent):

66. On that basis, I find that Bricmate’s assertions, set out in point 52 above, are correct in part:

(i) the volume of imports from China to the Union (d) fell by 14% between 2007 and the investigation period, not 3% as in the provisional regulation (nor quite 15% as Bricmate states);

(ii) Union consumption (c) fell by 30% over the whole period as stated by Bricmate, rather than 29% as in the provisional regulation;

(iii) Bricmate is correct to state that the market share of Chinese imports (e) increased by 1% rather than 1.7%, and never reached 6%, of Union consumption and that there was a fall in market share between 2008 and 2009, not steady growth over the whole period;

(iv) the market share of the Union industry (b as a proportion of c) did not fall by 1% (from 89% to 88%) between 2007 and the investigation period as stated in the provisional regulation; nor, however, did it remain entirely stable at 89% as asserted by Bricmate, but fell very slightly by 0.15%, from 89.03% to 88.88%;

(v) prices of Chinese imports (f) did not fall by 3% between 2007 and the investigation period but rose by 9% overall (not 10% as asserted by Bricmate);

(vi) the price differential between Chinese imports and the Union industry (f as compared with g) remained stable at 42% as stated by Bricmate, and did not increase from 40% to 50% as stated in the provisional regulation;

(vii) between 2008 and 2009 (when the Union industry’s profit margin fell from +0.6% to ‑1.2%), the market share of Chinese imports (e) did not rise from 5.3% to 5.6% but fell to 4.9%;

(viii) between 2009 and the end of the investigation period (when the Union industry’s profit margin recovered from ‑1.2% to +0.4%), the market share of Chinese imports (e) increased from 4.9% to 5.8%, not 6.5%;

(ix) between 2007 and 2009 (while Union consumption fell by 23%), the volume of Chinese imports (d) did not fall by 9% as stated in the provisional regulation, but by 20% as asserted by Bricmate.

67. Both the Council and the Commission argue, essentially, that the Commission did examine all the discrepancies (and I see no reason to cast doubt on that statement, made also in the general disclosure document and the definitive regulation) and found them to be insufficient, when taken together with all the other economic factors to be weighed in the balance, to affect the assessment of injury or causation. They consider that, while some trends were less pronounced than stated in the provisional regulation, the overall picture remained the same and continued to justify the conclusions drawn.

68. It seems to me that any differences identified under (ii) and (iv) above can be disregarded as insignificant.

69. As regards the remaining points, I consider that:

(i) the fact that the volume of imports from China to the Union (d) fell by 14% over the whole period must be placed against the fact that both consumption in the Union (c) and total imports (a) fell by slightly over twice that proportion (about 29% in both cases);

(iii) the fact that the market share of imports from China (e) increased overall by only 1% of Union consumption, and that there was a fall in market share between 2008 and 2009, must be placed against the fact that that market share was still 21% greater in the investigation period than it had been in 2007;

(v-vi) the fact that prices of imports from China (f) rose by 9% between 2007 and the investigation period must be placed against the fact that, as stated by Bricmate itself, the price differential between those imports and the Union industry remained roughly stable at the considerable level of around 42%;

(vii) the fact that the market share of imports from China (e) fell from 5.3% to 4.9% between 2008 and 2009 is consistent with all the other figures showing a shrinking of the market over that period but is not indicative of anything else;

(viii) the fact that the market share of imports from China (e) increased from 4.9% to 5.8% between 2009 and the end of the investigation period is consistent with the recovery of the market during that period as evidenced by other figures but is not indicative of anything else;

(ix) the fall of 20% in the volume of imports from China (d) between 2007 and 2009 must be placed against not only the fall of 23% in Union consumption (e) but also the fall of 22% in Union production sold in the Union (b) and of 29% in imports overall (a), in the same period.

70. In those circumstances, I can agree with the Council and the Commission that the statistical errors were not such as to call into question the conclusions reached in the contested regulation. Even if the volume, price and market share of imports from China followed overall trends in the Union rather more closely than appeared from the official statistics actually used in the regulations, there remain clear indications that the Union industry suffered injury from imports, and that there was a causal link between imports from China and that injury.

71. It is true that simple injury is not sufficient to justify antidumping measures. Pursuant to Article 3(6) of the basic regulation, it must be demonstrated that the volume and/or price levels identified are responsible for an impact on the Union industry, and that this impact exists to a ‘material’ degree.

72. However, it is settled case-law that such matters fall within the institutions’ broad discretion in the appraisal of complex economic and political situations, and the Court’s review is therefore limited to verifying that there have been no manifest errors of assessment. (18)

73. In the present case, in particular, imports from China were priced at less than 60% of the prices of the Union industry, and they increased both as a proportion of sales on the Union market and as a proportion of total imports into the Union. Moreover, the factual errors which I have set out in points 66 and 69 above do not appear so momentous as to indicate that the institutions should have drawn different conclusions from the corrected figures from those which they drew from the erroneous figures. Finally, most of the factors which the Commission took into consideration when assessing injury (for instance, the evolution of employment and productivity over the period considered, or the increase in the stocks of the Union industry) remain unaffected by the errors of fact identified.

74. It seems to me, therefore, that there is no justification for concluding that the institutions’ conclusions concerning the existence and level of dumping, and the existence and material nature of injury to the Union industry, were manifestly (or even necessarily at all) erroneous even if a certain number of the detailed facts on which they were based contained errors.

75. Those same considerations lead me also to dismiss Bricmate’s further submissions set out in point 56 above, alleging an error of assessment at recital 108 in the definitive regulation.

Second part of the first plea in the main proceedings (failure to exercise due care and disregard of Article 3(2) and (6) of the basic regulation; point 3 of the question referred)

Submissions

76. In the second part of its first plea in the main proceedings, Bricmate alleged that the institutions had failed in their obligation to exercise due care and had disregarded Article 3(2) and (6) of the basic regulation, in that Bricmate (and other operators which cooperated in the investigation) had protested to the Commission that the Eurostat statistics appeared to be incorrect but the institutions failed to investigate and correct the error.

77. Bricmate argues that the institutions failed to investigate and correct the error — contrary to the requirements of Article 3(2) and (6) of the basic regulation. Recital 108 in the definitive regulation shows that the institutions did not fulfil their duties in that regard. Bricmate here invokes settled case-law to the effect that the Courts of the Union must satisfy themselves that the institutions took account of all the relevant circumstances and appraised the facts with all due care. (19)

78. Bricmate also stresses how easy it was to ascertain the error in the figures for imports to Spain in November 2009, and cites GLS: ‘As [Advocate General Bot] stated in points 101 and 102 of his Opinion, the Commission has an obligation to consider on its own initiative all the information available, since in an anti-dumping investigation, it does not act as an arbitrator whose remit is limited to making an award solely on the basis of the information and the evidence provided by the parties to the investigation. In that connection, it should be noted that Article 6(3) and (4) of the basic regulation authorises the Commission to request Member States to supply information to it and to carry out all necessary checks and inspections.’ (20) The failures are particularly serious in the present case, since several operators had drawn attention to the anomalous figures, and Eurostat is part of the Commission.

79. The Council and Commission both submit that Bricmate’s arguments are unfounded. The figures were carefully examined; the Commission verified whether the conclusions on injury and causation could have been any different if the Eurostat figures had been adjusted (even though they could not in fact be adjusted in good time), and reached the view that the conclusions could not have been different. All the conclusions were reached on the basis of objective facts, taken globally, not only on the Eurostat figures impugned by Bricmate.

Assessment

80. It seems to me that the second part of the plea must share the same fate as the first part.

81. If the definitive regulation were to be annulled because, on the basis of the adjusted figures, the institutions could not have reached the conclusions which they did reach, there would be no cogent reason to go further and look at the duty of care or compliance with Article 3(2) and (6) of the basic regulation.

82. However, I have examined the figures and considered that the institutions could justifiably reach those conclusions. Bricmate’s arguments on the second part of the plea therefore seem to me to fall away. While it must be acknowledged that the error in the Spanish statistics for November 2009 was such that it should have been immediately obvious, the fact remains that the Spanish authorities did not correct it in good time and that the Commission was not in a position to correct the error itself, but that (crucially) it did consider whether the discrepancies brought to its notice could have affected the conclusions drawn.

Second plea in the main proceedings (failure to state adequate reasons, failure to respect rights of defence, disregard of Article 17 of the basic regulation; points 4 to 6 of the question referred)

Submissions

83. In its second plea in the main proceedings, Bricmate submitted that the Commission had failed in its duty to state reasons, had not taken account of Bricmate’s rights of defence and had disregarded Article 17 of the basic regulation by not taking into consideration Bricmate’s arguments, presented in its capacity as a selected independent importer, regarding differences in the manufacturing processes of Chinese and European tile producers and the supply of tiles on the Union market.

84. Bricmate stresses that, as part of the selected sample of unrelated importers, it specified seven types of tile range which it could not obtain in the Union because of differences in the cutting process, and pointed out that the PCNs used and the injury calculations did not take account of these differences. An adjustment would have resulted in a lower injury margin. Moreover, the Union industry could not supply small tiles. However, that information was not taken into account, and Bricmate’s opinions were not taken as representative of other, non-selected importers but were disregarded by reference to other information. It refers to Gul Ahmed: (21) ‘where sampling is carried out in accordance with Article 17 of the basic regulation, the EU institutions must, in principle, take into consideration the data concerning the exports of all the undertakings in the sample’; the same should apply where the sampling concerns independent importers. The failure to take account of Bricmate’s information entailed a failure to state adequate reasons.

85. Moreover, the Commission failed to comply with Article 20(1) of the basic regulation by neglecting to inform Bricmate of the ‘essential facts and considerations’ on the basis of which provisional measures had been imposed. When it dismissed Bricmate’s argument relating to a shortage of tiles in smaller sizes by referring to other information, the Commission failed to state reasons and violated Bricmate’s rights of defence: it was not stated what other information was involved, and the answer was not received until 27 July 2011, too late for Bricmate to obtain more evidence.

86. Finally, the Commission, by claiming that it had not obtained any data which demonstrated a ‘serious risk of shortage of supply’ of tiles, disregarded Bricmate’s evidence of 15 April 2011. Information from all importers in the sample should be taken into account. Since Bricmate was included, its information should be regarded as representative for the other, non-selected, SMEs. That information should therefore have been taken as evidence that the anti-dumping measures would lead to a serious shortage for SMEs, which could not source products from the Union industry or third countries because of the non-availability of a cutting process and because of small order volumes. The Commission thus breached the rules governing selection in Article 17 of the basic regulation and made a manifestly incorrect assessment.

87. The Council submits, first, that Bricmate’s information was not ignored, but the Commission found that the types of tile not found in the Union were available from producers in a number of third countries other than China. That answer was given to Bricmate and referred to in both the provisional regulation and the definitive regulation, and the variety of sources was mentioned even in the General Court’s order. (22) Four other sampled importers said they were able to change their sources of supply.

88. Second, the institutions examined Bricmate’s allegations concerning the difference in production processes carefully and explained, both to Bricmate and in the two regulations, why those allegations were considered unfounded. The Commission responded to all of Bricmate’s arguments to the extent that they were relevant to the investigation. For Bricmate’s rights of defence to have been infringed, it would have been necessary, first, that there had been a procedural irregularity and, second, that there was a possibility that, due to that irregularity, the administrative procedure could have resulted in a different outcome. (23)

89. Finally, all of Bricmate’s submissions were examined during the investigation and compared with those of the other importers in the sample, all the submissions being accorded equal importance.

90. The Commission states that it took all Bricmate’s submissions into account, but reached a different conclusion. It refers in detail to the various letters and recitals in which it responded to those submissions, and points out that the General Court had found that Bricmate was not justified in claiming that the imposition of the anti-dumping duties, which concern only the imports of the products at issue from China, necessarily had serious consequences for its economic activities. (24)

Assessment

91. Bricmate’s arguments concern an alleged failure to take its submissions to the Commission — essentially, its claims that certain types of tile, defined by quality and cutting method, could not be obtained from sources other than in China — into consideration. As a corollary, in Bricmate’s view, the statement of reasons in the definitive regulation was inadequate, and the Commission neither took proper account of Bricmate’s status as a sampled importer in accordance with Article 17 of the basic regulation nor disclosed the details underlying the essential considerations on the basis of which anti-dumping measures were imposed, contrary to Article 20(1) of the same regulation. The institutions’ reply is essentially that those submissions were taken into consideration, but that the conclusions drawn, following examination, were not the same as those drawn by Bricmate, and that responses were given to the various submissions.

92. I am unconvinced by Bricmate’s arguments, bearing in mind that they concern whether its submissions were taken into consideration, not whether the consideration of those submissions was adequate.

93. It seems to me clear from the correspondence and recitals which I have set out at points 10, 13, 22 to 27 and 32 above that first the Commission, then the Council, took Bricmate’s submissions (together, apparently, with submissions of a similar nature from one or more other interested parties) into consideration.

94. It would obviously place a prohibitive burden on the institutions (in particular the Commission) if, in the course of an anti-dumping investigation, they were required to respond individually to every detailed point made by every interested party. What is essential is that a sufficient response be given to enable the party in question to understand that the points were considered, that a particular view was reached and that the view was based on identifiable reasons. It can then (if it so chooses) seek to contest the adequacy of the way in which its submissions were considered.

95. Those requirements appear to me to be met here.

Conclusion

96. In the light of all the above considerations, I am of the opinion that the Court should answer the Förvaltningsrätten i Malmö to the effect that Council Implementing Regulation (EU) No 917/2011 of 12 September 2011 imposing a definitive anti-dumping duty and collecting definitively the provisional duty imposed on imports of ceramic tiles originating in the People’s Republic of China is not invalid on any of the grounds raised in its request for a preliminary ruling.