JUDGMENT OF THE COURT OF FIRST INSTANCE (First Chamber)

29 September 2009 (*)

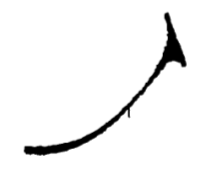

(Community trade mark − International registration designating the European Community – Figurative mark representing half a smiley smile – Absolute ground for refusal – Lack of distinctive character – Article 146(1) and Article 7(1)(b) of Regulation (EC) No 40/94 (now Article 151(1) and Article 7(1)(b) of Regulation (EC) No 207/2009)

In Case T‑139/08,

The Smiley Company SPRL, established in Brussels (Belgium), represented by A. Deutsch, lawyer,

applicant,

v

Office for Harmonisation in the Internal Market (Trade Marks and Designs) (OHIM), represented by J. Crespo Carrillo, acting as Agent,

defendant,

ACTION brought against the decision of the Fourth Board of Appeal of OHIM of 7 February 2008 (R 958/2007-4) concerning the international registration, designating the European Community, of the figurative mark representing half a smiley smile,

THE COURT OF FIRST INSTANCE OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES (First Chamber),

composed of V. Tiili, President, F. Dehousse and I. Wiszniewska-Białecka (Rapporteur), Judges,

Registrar: K. Pocheć, Administrator,

having regard to the application lodged at the Registry of the Court of First Instance on 11 April 2008,

having regard to the response lodged at the Registry of the Court of First Instance on 31 July 2008,

having regard to the Court’s written question to the parties,

having regard to the observations lodged by the parties at the Registry of the Court of First Instance on 8, 15 and 30 April 2009,

having regard to the order of 4 June 2009 authorising the replacement of a party to the proceedings,

further to the hearing on 10 June 2009,

gives the following

Judgment

Background to the dispute

1 On 14 April 2006 Mr Franklin Loufrani obtained an international registration, designating the European Community, for the figurative mark reproduced below (‘the mark at issue’):

2 The Office for Harmonisation in the Internal Market (Trade Marks and Designs) (OHIM) received notification of the international registration of the mark at issue on 14 September 2006.

3 The goods in respect of which the protection of that mark is claimed in the Community are in Classes 14, 18 and 25 of the Nice Agreement concerning the International Classification of Goods and Services for the purposes of the Registration of Marks of 15 June 1957, as revised and amended, and correspond, for each of those classes, to the following description:

– Class 14: ‘Precious metals and alloys thereof other than for dental use, jewellery, precious stones, timepieces and chronometric instruments, silverware (dishes), works of art of precious metal, boxes, cases and chests of precious metal, bracelets (jewellery), brooches (jewellery), sun dials, ashtrays (of precious metal) for smokers, chains (jewellery), hat ornaments (of precious metal), chronographs (watches), chronometers, fancy key rings, necklaces (jewellery), tie pins, household and kitchen containers, kitchen and household utensils of precious metal, pins (jewellery), clocks, badges of precious metal, cuff links, medals, purses of precious metal, watches, watchbands, silverware (with the exception of cutlery, table forks and spoons), ornaments (jewellery), wall clocks (timepieces), napkin holders of precious metal, alarm clocks, services (tableware) of precious metal, urns of precious metal, sacred vessels of precious metal’;

– Class 18: ‘Trunks and suitcases, umbrellas, parasols and walking sticks, whips and saddlery, animal collars and leashes, boxes of leather or leather board, purses, walking-stick seats, satchels, card cases (wallets), hat boxes of leather, key cases (leatherware), vanity cases, document holders, school bags, net bags for shopping, clothing for animals, attaché cases, change purses (not of precious metal), sunshades, wallets, sling bags for carrying infants, backpacks, handbags, beach bags, travelling bags, bags (envelopes, pouches) for packaging (of leather), garment bags (for travel), briefcases (leatherware), travelling sets (leatherware)’;

– Class 25: ‘Clothing, footwear (except orthopaedic footwear), bathing suits, bath robes, bibs not of paper, berets, hosiery, boots, suspenders, boxer shorts, caps, belts (clothing), hats, sports shoes, masquerade costumes, diaper pants, ear muffs (clothing), neckties, sashes for wear, scarves, gloves (clothing), layettes, slippers, soles, underwear, aprons (clothing), sportswear’.

4 On 1 February 2007, OHIM notified an ex officio provisional refusal of protection in the Community of the mark at issue, pursuant to Article 5 of the Protocol relating to the Madrid Agreement concerning the international registration of marks, adopted at Madrid on 27 June 1989 (OJ 2003 L 296, p. 22) and to Rule 113 of Commission Regulation (EC) No 2868/95 of 13 December 1995 implementing Council Regulation (EC) No 40/94 on the Community trade mark (OJ 1995 L 303, p. 1), as amended, for all the goods covered by the international registration designating the Community. The ground put forward was that the mark at issue lacked distinctive character in terms of Article 7(1)(b) of Council Regulation (EC) No 40/94 of 20 December 1993 on the Community trade mark (OJ 1994 L 11, p. 1), as amended (now Article 7(1)(b) of Council Regulation (EC) No 207/2009 of 26 February 2009 on the Community trade mark (OJ 2009 L 78, p. 1).

5 Since there was no reply to that notification within the time-limit, the examiner, by decision of 23 April 2007, refused protection of the mark at issue in the Community for all the goods covered by the international registration designating the Community, on the ground that the mark at issue was devoid of any distinctive character within the meaning of Article 7(1)(b) of Regulation No 40/94.

6 On 22 June 2007, Mr Loufrani filed a notice of appeal with OHIM against that decision, under Articles 57 to 62 of Regulation No 40/94 (now Articles 58 to 64 of Regulation No 207/2009).

7 By decision of 7 February 2008 (‘the contested decision’), the Fourth Board of Appeal of OHIM dismissed the appeal. The Board of Appeal found that the goods in respect of which protection was claimed were common consumer goods, that the relevant public was the general public of the Community, and that, considering that what were involved were ‘items of jewellery, leatherware, clothing and the like’, that public would pay a relatively high degree of attention when choosing those goods. Regarding the mark at issue, first, the Board of Appeal upheld the examiner’s assessment that it was a very simple and ordinary design, with an exclusively decorative function, and would not be perceived by the relevant public as a distinctive sign. Secondly, it dismissed as unconvincing the examples of registered marks relied on in support of the appeal. In light of those factors, the Board found that the mark at issue was devoid of any distinctive character within the meaning of Article 7(1)(b) of Regulation No 40/94 and that the protection of the mark at issue in the Community had therefore to be refused.

8 Following the transfer of the international registration of the mark at issue, the applicant, The Smiley Company SPRL, was granted leave to substitute itself for Mr Loufrani in the present proceedings.

Forms of order sought

9 The applicant claims the Court should:

– annul the contested decision;

– order OHIM to pay the costs.

10 OHIM contends that the Court should:

– dismiss the action;

– order the applicant to pay the costs.

Law

11 The applicant raises a single plea in law, alleging infringement of Article 7(1)(b) of Regulation No 40/94. It submits, in essence, that the relevant public comprises average consumers, some of whom pay a particularly high degree of attention, at least with regard to some of the goods in question, and is accustomed to identifying as an indicator of commercial origin numerous signs similar to the mark at issue. In addition, that mark is already used to indicate the commercial origin of certain products and has characteristics that are sufficiently specific for it to be regarded as possessing the minimum degree of distinctiveness required in order for it to be protected in the Community.

12 OHIM disputes the applicant’s arguments.

13 Under Article 146(1) of Regulation No 40/94 (now Article 151(1) of Regulation No 207/2009), an international registration designating the Community is, from the date of its registration pursuant to Article 3(4) of the Madrid Protocol, to have the same effect as an application for a Community trade mark. Article 149(1) of Regulation No 40/94 (now Article 154(1) of Regulation No 207/2009) provides that international registrations designating the Community are to be subject to examination as to absolute grounds for refusal in the same way as applications for Community trade marks.

14 According to Article 7(1)(b) of Regulation No 40/94, trade marks which are devoid of any distinctive character are not to be registered. According to settled case-law, the marks referred to in Article 7(1)(b) of Regulation No 40/94 are those which are regarded as incapable of performing the essential function of a trade mark, namely that of identifying the commercial origin of the goods or services at issue, thus enabling the consumer who acquired them to repeat the experience if it proves to be positive, or to avoid it if it proves to be negative, on the occasion of a subsequent acquisition (Case T-34/00 Eurocool Logistik v OHIM (EUROCOOL) [2002] ECR II-683, paragraph 37, and Case T‑449/07 Rotter v OHIM (Shape of an arrangement of sausages) [2009] ECR II-0000, paragraph 18).

15 The distinctive character of a mark must be assessed, first, by reference to the goods or services in respect of which registration or the protection of the mark has been applied for and, second, by reference to the perception of the relevant public, which consists of average consumers of those goods or services (Case T-88/00 Mag Instrument v OHIM (Torch shapes) [2002] ECR II-467, paragraph 30, and Shape of an arrangement of sausages, paragraph 14 above, paragraph 19).

16 A minimum degree of distinctive character is, however, sufficient to render the absolute ground for refusal set out in Article 7(1)(b) of Regulation No 40/94 inapplicable (Case T-337/99 Henkel v OHIM (Round red and white tablet) [2001] ECR II-2597, paragraph 44, and Joined Cases T-405/07 and T-406/07 CFCMCEE v OHIM (P@YWEB CARD and PAYWEB CARD) [2009] ECR II-0000, paragraph 57).

17 In the present case, the protection of the mark at issue in the Community was refused in respect of all the goods for which that protection had been claimed. Those goods are, in essence, precious metals, goods made of precious metals, items of jewellery and timepieces, all in Class 14, leatherware and luggage in Class 18 and clothing and clothing accessories in Class 25. As those goods are, in essence, intended for the general public, the Board of Appeal was right to find that the relevant public is the general public in the Community. Furthermore, that has not been disputed by the applicant.

18 The way in which the relevant public perceives a trade mark is, however, influenced by the average consumer’s level of attention, which is likely to vary according to the category of goods or services in question (Round red and white tablet, paragraph 16 above, paragraph 48, and Case T-358/04 Neumann v OHIM (Shape of a microphone head) [2007] ECR II-3329, paragraph 40).

19 In the present case, even although the relevant public might pay a relatively high degree of attention when choosing the goods in question, as pointed out by the Board of Appeal, that public cannot be considered to exhibit a particularly high degree of attention, as submitted by the applicant, even with regard to some of the goods in question. Although those goods may in fact be regarded as part of the fashion sector in the broad sense and it may be accepted that average consumers pay some attention to their appearance and are therefore capable of assessing the style, quality, finish and price of such goods when they purchase them, it is not apparent from the description of the goods in question that they are luxury goods or goods which are so sophisticated or expensive that the relevant public would be likely to be particularly attentive with regard to them.

20 The distinctiveness of the mark at issue must therefore be assessed in respect of all the goods for which protection of that mark has been claimed, taking into account the presumed expectations of an average consumer who does not display a particularly high level of attention.

21 The mark at issue is composed of a curved, ascending line, comparable to a quarter of a circle, under the middle of which there is a small vertical stroke, and ends, on the right-hand side, with a second short line, almost perpendicular to the first. A vaguely triangular shape marks the intersection of the two main lines. The various elements form a whole.

22 At the hearing, the applicant submitted that the small vertical stroke under the ascending curve of the trade mark at issue was not part of that mark but the result of poor print quality, and the Court took formal note thereof. However, OHIM argued that that argument was inadmissible on the ground that it changed the subject-matter of the proceedings before the Board of Appeal in breach of Article 135(4) of the Rules of Procedure of the Court of First Instance, and the Court also took formal note thereof.

23 It is apparent from the file on the procedure before OHIM that the examiner described the mark at issue as ‘a black ascending line which ends, at the top right-hand side, with a short stroke, perpendicular to that line’ and that, in its written pleading setting out the grounds of its appeal before the Board of Appeal, Mr Loufrani stated that ‘it was necessary to draw attention to the small vertical stroke underneath the curve …, an element which the examiner does not mention’. It is thus at Mr Loufrani’s express request that the Board of Appeal regarded that small stroke as forming part of the mark at issue.

24 According to the case-law, it is apparent from Article 63 of Regulation No 40/94 (now Article 65 of Regulation No 207/2009) and Article 135(4) of the Rules of Procedure that an applicant does not have the power to alter before the Court of First Instance the terms of the dispute, as delimited in the respective claims and allegations submitted before OHIM. Consequently, an argument expounded for the first time at the hearing before the Court of First Instance and having such an effect must be rejected as inadmissible (see, to that effect, Case C-412/05 P Alcon v OHIM [2007] ECR I-3569, paragraphs 43 to 45, and the case-law cited).

25 In the present case, the argument put forward by the applicant at the hearing has the effect of altering the mark for which it claims protection in the Community and with regard to which the Board of Appeal adjudicated. As OHIM contends, that argument changes the subject-matter of the proceedings before the Board of Appeal as resulting from the claims the applicant made before OHIM. That argument must therefore be rejected as inadmissible and the small vertical stroke must be regarded as part of the mark at issue.

26 As regards that mark’s distinctiveness, it must be borne in mind that, according to the case-law, a sign which is excessively simple and is constituted by a basic geometrical figure, such as a circle, a line, a rectangle or a conventional pentagon, is not, in itself, capable of conveying a message which consumers will be able to remember, with the result that they will not regard it as a trade mark unless it has acquired distinctive character through use (judgment of 12 September 2007 in Case T‑304/05 Cain Cellars v OHIM (Representation of a pentagon), not published in the ECR, paragraph 22).

27 That being so, a finding that a mark has distinctive character within the meaning of Article 7(1)(b) of Regulation No 40/94 is not subject to a finding of a specific level of linguistic or artistic creativity or imaginativeness on the part of the proprietor of the trade mark. It suffices that the trade mark should enable the relevant public to identify the origin of the goods or services it covers and to distinguish them from those of other undertakings (Case C-329/02 P SAT.1 v OHIM [2004] ECR I-8317, paragraph 41, and Case T-23/07 Borco-Marken-Import Matthiesen v OHIM (α) [2009] ECR II-0000, paragraph 43).

28 In the present case, it is common ground that the mark at issue does not represent a geometrical figure. However, the parties are in dispute as to the degree of simplicity and, consequently, the distinctive character of that mark, the applicant maintaining, in essence, that the mark at issue is a ‘fairly complex arrangement of two lines … which resembles a little bit the letter “t”’ and that it is therefore distinctive.

29 In that regard, it must be pointed out, first, that, contrary to what the applicant states, the Board of Appeal did not disregard the stroke at the right-hand side of the curve and the fact that it allows the mark at issue to make an impression different from that of a simple curved line. It is apparent from the contested decision that the Board of Appeal, first, adopted by implication the examiner’s description of the mark at issue, which is set out in paragraph 23 above, secondly, supplemented it in accordance with what was stated in the grounds of appeal before the Board of Appeal, by pointing out the ‘small stroke in the middle of the curve, towards the bottom’ and, lastly, found that that small stroke did not alter the perception of the mark at issue as being ‘a very simple and banal design, which has an exclusively decorative function and not that of identifying the commercial origin of the goods’.

30 Secondly, it is true that the applicant is justified in maintaining that whether or not a mark may serve a decorative or ornamental purpose is irrelevant for the purposes of assessing its distinctive character. A sign which fulfils functions other than that of a trade mark in the traditional sense of the term is only distinctive for the purposes of Article 7(1)(b) of Regulation No 40/94, however, if it may be perceived immediately as an indication of the commercial origin of the goods or services in question, so as to enable the relevant public to distinguish, without any possibility of confusion, the goods or services of the owner of the mark from those of a different commercial origin (Case T-130/01 Sykes Enterprises v OHIM (REAL PEOPLE, REAL SOLUTIONS) [2002] ECR II-5179, paragraph 20, and Case T-320/03 Citicorp v OHIM (LIVE RICHLY) [2005] ECR II-3411, paragraph 66). It is thus necessary for that sign, even if it is decorative, to have a minimum degree of distinctive character.

31 There is no aspect of the trade mark at issue which may be easily and instantly memorised by an even relatively attentive relevant public and which would make it possible for it to be perceived immediately as an indication of the commercial origin of the goods in question. As was correctly pointed out by the Board of Appeal, it will be perceived exclusively as a decorative element whether it relates to goods in Class 14 or to those in Classes 18 and 25. Thus, the mark at issue does not make it possible for any of the goods at issue to be distinguished from competing goods.

32 That finding cannot be called into question by the fact that the relevant public is used to perceiving figurative signs that are simply stripes as trade marks or that numerous manufacturers have registered such marks to designate goods in Class 25.

33 Contrary to what the applicant maintains, the Board of Appeal did not assert that the relevant public (in particular consumers of goods in Class 25) was not used to seeing simple stripe designs as distinctive signs. Nor, furthermore, did it assert that consumers do not pay attention to such stripe designs to distinguish between goods. It is apparent from the contested decision that the Board of Appeal merely observed that the examples submitted were not convincing because they were marks which were different from and more complex than the mark at issue.

34 That view on the part of the Board of Appeal must be upheld. First, what must be ascertained in this case is whether the mark at issue is, per se, capable of being perceived, by the relevant public as an indication which makes it possible for it to identify the commercial origin of the goods in question without any possibility of confusion with those of a different origin. Accordingly, the mere fact that other marks, although equally simple, have been regarded as being so capable and, therefore, as not being devoid of any distinctive character, is not conclusive for the purpose of establishing whether the mark at issue also has the minimum degree of distinctive character necessary for protection in the Community.

35 Secondly, even if the applicant’s line of argument were admissible in its entirety, since some of the marks were cited for the first time before the Court, it must be acknowledged that the numerous marks to which the applicant refers are simple. However, they all consist not only of simple lines or strokes, like the mark at issue, but are either identifiable shapes which have a certain surface area (solid or in outline), such as stripes, parallelepipeds, commas, stylised letters, or combinations of such shapes. The Board of Appeal therefore rightly pointed out that the marks cited before it were designs which create an overall impression of a surface area. That is not true of the mark at issue. Consequently, the applicant’s assertion that the marks to which it refers have the same characteristics as those of the mark at issue or that the mark at issue is of the same complexity as the marks which it cites cannot be accepted. It follows that the fact that consumers of certain goods in Class 25 are used to perceiving such shapes or combinations of shapes as an indication of the commercial origin of those goods is not conclusive in the present case.

36 Thirdly, the minimum degree of distinctiveness required for the purposes of registration or protection in the Community must be assessed in the light of the circumstances of each case. Decisions concerning registration or the protection of a sign as a Community trade mark which the Boards of Appeal are called on to take under Regulation No 40/94 are adopted in the exercise of circumscribed powers. Accordingly, the legality of the decisions of Boards of Appeal must be assessed solely on the basis of that regulation, as interpreted by the Community judicature, and not on the basis of a previous decision-making practice of those boards (Case C-37/03 P BioID v OHIM [2005] ECR I-7975, paragraph 47, and Alcon v OHIM, paragraph 24 above, paragraph 65). Consequently, the fact that simple stripe signs have been registered by OHIM as Community trade marks is not relevant for the purposes of assessing whether or not the mark at issue is devoid of any distinctive character within the meaning of Article 7(1)(b) of Regulation No 40/94.

37 It follows that the Board of Appeal was right to find that the mark at issue is a very simple and banal design, which has an exclusively decorative function and would not be perceived as an indication of the commercial origin of the goods in question.

38 That conclusion cannot be called into question by the argument that the mark at issue is already used as an indication of commercial origin. Article 7(1)(b) of Regulation No 40/94 requires an analysis of a mark’s distinctiveness to be carried out without reference to any actual use of that mark for the purposes of Article 7(3) of Regulation No 40/94 (now Article 7(3) of Regulation No 207/2009) (Case T-87/00 Bank für Arbeit und Wirtschaft v OHIM (EASYBANK) [2001] ECR II-1259, paragraph 40, and Case T-360/03 Frischpack v OHIM (Shape of a cheese box) [2004] ECR II-4097, paragraph 29). Furthermore, the purpose of actions before the Court of First Instance is to review the legality of decisions of the Boards of Appeal of OHIM within the meaning of Article 63 of Regulation No 40/94. Consequently, it is not the Court’s function to re-evaluate the factual circumstances in the light of evidence adduced for the first time before it. To admit such evidence is contrary to Article 135(4) of the Rules of Procedure, which prohibits the parties from changing the subject-matter of the proceedings before the Board of Appeal (Case T‑128/01 DaimlerChrysler v OHIM (Grille) [2003] ECR II-701, paragraph 18, and α, paragraph 27 above, paragraph 9). It is apparent from the file on the proceedings before OHIM that the photographs produced by the applicant in support of that argument were produced for the first time before the Court and that the applicant did not claim before OHIM that the mark at issue had become distinctive in consequence of the use which had been made of it. Therefore that argument and the evidence adduced in support of it must be rejected as inadmissible.

39 Lastly, the argument that the mark at issue is identified by the relevant public as a ‘half smiley mouth’, the smiley itself having been registered as Community trade mark No 517383, and that it is therefore distinctive cannot be upheld, even if that argument, which was formulated for the first time before the Court, were to be admissible. As OHIM states, to follow that approach would be tantamount to accepting that every extract from a registered mark and, therefore, every extract from a distinctive mark, is by reason of that fact alone also distinctive for the purposes of Article 7(1)(b) of Regulation No 40/94. That cannot be accepted. The assessment of the distinctive character of a mark for the purposes of that provision must be based on that mark’s ability to distinguish the applicant’s goods or services on the market from goods or services of the same type offered by competitors (Case T-79/00 Rewe-Zentral v OHIM (LITE) [2002] ECR II-705, paragraph 30). The fact that the mark at issue consists of part of a mark which has already been registered is not relevant in that regard.

40 In any event, although the mark at issue may, when the marks are compared side by side, be found to resemble half of the mouth in Community trade mark No 517383, it must be recalled that the average consumer must place his trust in the imperfect picture of the mark that he has kept in his mind (Case T-316/00 Viking-Umwelttechnik v OHIM (Juxtaposition of green and grey) [2002] ECR II-3715, paragraph 28, and judgment of 12 November 2008 in Case T-400/07 GretagMacbeth v OHIM (Combination of 24 coloured squares), not published in the ECR, paragraph 47). Furthermore, the relevant public’s recognition, in the mark at issue, of part of Community trade mark No 517383 presupposes that the relevant public knows the latter mark, a fact that the applicant has not established. It cannot therefore be considered that, when it perceives the mark at issue, the relevant public will identify it as half of a smiley mouth or half of the smile in Community trade mark No 517383. In that regard, it must also be stated, as OHIM pointed out, that the small vertical stroke under the principal curve of the mark at issue does not appear in the mouth in Community trade mark No 517383. The possible association of the mark at issue with the mark cited by the applicant has not therefore been proved.

41 It follows from all of the foregoing that the Board of Appeal did not err in finding that the mark at issue was devoid of the minimum degree of distinctiveness necessary to avoid the absolute ground for refusal in Article 7(1)(b) of Regulation No 40/94 and that protection of that mark in the Community should therefore be refused. Accordingly, the single plea alleging infringement of Article 7(1)(b) of Regulation No 40/94 must be rejected as unfounded, together with the action in its entirety.

Costs

42 Under Article 87(2) of the Rules of Procedure, the unsuccessful party is to be ordered to pay the costs if they have been applied for in the successful party’s pleadings. Since the applicant has been unsuccessful, it must be ordered to pay the costs, including those connected with its substitution for Mr Loufrani as applicant, in accordance with the forms of order sought by OHIM.

On those grounds,

THE COURT OF FIRST INSTANCE (First Chamber)

hereby:

1. Dismisses the action;

2. Orders The Smiley Company SPRL to pay the costs, including those connected with its substitution for Mr Franklin Loufrani.

Tiili | Dehousse | Wiszniewska-Białecka |

Delivered in open court in Luxembourg on 29 September 2009.

[Signatures]