JUDGMENT OF THE COURT OF FIRST INSTANCE (Second Chamber)

15 June 2005 (*)

(Competition – Cartels – Specialty graphite market – Price fixing – Liability – Calculation of fines – Cumulation of penalties – Duty to state reasons – Rights of the defence – Guidelines on the method of setting fines – Applicability – Gravity and duration of the infringement – Attenuating circumstances – Aggravating circumstances – Ability to pay – Co-operation during the administrative procedure – Methods of payment)

In Joined Cases T-71/03, T-74/03, T-87/03 and T-91/03,

Tokai Carbon Co. Ltd, established in Tokyo (Japan), represented by G. van Gerven and T. Franchoo, lawyers, with an address for service in Luxembourg,

Intech EDM BV, established in Lomm (Netherlands), represented by M. Karl and C. Steinle, lawyers,

Intech EDM AG, established in Losone (Switzerland), represented by M. Karl and C. Steinle, lawyers,

SGL Carbon AG, established in Wiesbaden (Germany), represented by M. Klusmann and P. Niggemann, lawyers,

applicants,

v

Commission of the European Communities, represented by W. Mölls, P. Hellström, F. Castillo de la Torre and S. Rating, acting as Agents, assisted, in Cases T-74/03 and T-87/03, by H.‑J. Freund, lawyer, with an address for service in Luxembourg,

defendant,

ACTIONS for annulment in full or in part of Commission Decision C(2002) 5083 final of 17 December 2002 relating to a proceeding under Article 81 EC and Article 53 of the EEA Agreement (Case COMP/E-2/37.667 – Speciality Graphite),

THE COURT OF FIRST INSTANCE OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES (Second Chamber),

composed of J. Pirrung, President, A.W.H. Meij and N.J. Forwood, Judges,

Registrar: J. Palacio González, Principal Administrator,

having regard to the written procedure and further to the hearing on 21 September 2004,

gives the following

Judgment

Background to the dispute

1 By Decision C(2002) 5083 final of 17 December 2002 relating to a proceeding under Article 81 EC and Article 53 of the EEA Agreement (Case COMP/E‑2/37.667 – Specialty Graphite, ‘the Decision’), the Commission found that various undertakings had participated in a series of agreements and concerted practices within the meaning of Article 81(1) EC and Article 53(1) of the Agreement on the European Economic Area (‘EEA’) in the specialty graphite sector in the period from July 1993 to February 1998.

2 For the purposes of the Decision, ‘specialty graphite’ describes a group of graphite products, namely isostatic graphite, extruded graphite and moulded graphite used in diverse applications. It does not include steel-making graphite electrodes.

3 The mechanical characteristics of isostatic graphite are superior to those of extruded and moulded graphite and the price of each graphite category varies according to its mechanical characteristics. Isostatic graphite is used, inter alia, in the manufacture, by electrical-discharge machining, of metal moulds for the automobile and electronics industries. It is also used to make dies for the continuous casting of non-ferrous metals such as copper and copper alloys.

4 The production cost differential between isostatic graphite and extruded or moulded graphite is at least 20%. In general, extruded graphite is the cheapest and is therefore chosen if it meets the user’s requirements. Extruded products are used in a wide range of industrial applications, mainly in the iron and steel, aluminium and chemical industries and in metallurgy.

5 Moulded graphite is generally used only in large-scale applications, because it is typically inferior to extruded graphite.

6 In general, specialty graphite products are supplied to customers either directly from the manufacturing plants as finished machined products or through intermediary machine shops. These machine shops buy unmachined graphite (in blocks or rods), machine them (i.e. customise the product according to the customer’s needs) and sell the machined products to the end-user.

7 The Decision concerns two separate cartels, one relating to the market for isostatic specialty graphite and the other to that for extruded specialty graphite. There was no evidence of an infringement in respect of moulded graphite. Those cartels covered very specific products, namely graphite in the form of standard and cut blocks, but not machined products, that is made to order for the customer.

8 The major producers of specialty graphite in the western world are multinational corporations. Worldwide specialty graphite sales in 2000 were about EUR 900 million. Of this figure, isostatic graphite accounted for around EUR 500 million and extruded graphite for EUR 300 million. At Community/EEA level, sales in 2000 were EUR 100 to 120 million for isostatic graphite and EUR 60 to 70 million for extruded graphite. Unmachined products accounted for about EUR 35 to 50 million in the isostatic market and about EUR 30 million in the extruded market.

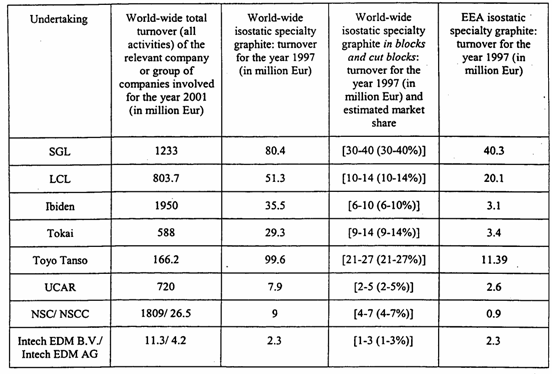

9 When the Decision was adopted, the largest producers of isostatic specialty graphite in the Community/EEA were the German company SGL Carbon AG (‘SGL’) and the French company Le Carbone-Lorraine SA (‘LCL’). The Japanese company Toyo Tanso Co. Ltd (‘TT’) ranked third, followed by other Japanese companies, namely Tokai Carbon Co. Ltd (‘Tokai’), Ibiden Co. Ltd (‘Ibiden’), Nippon Steel Chemical Co. Ltd (‘NSC’) and NSCC Techno Carbon Co. Ltd (‘NSCC’) and the American company UCAR International Inc. (‘UCAR’), which became GrafTech International Ltd.

10 In addition to these producers, Intech EDM BV, a company established under Netherlands law, and its Swiss subsidiary Intech EDM AG (also referred to together as ‘Intech’), operated in the isostatic graphite sector. Intech did not have production facilities. Under a cooperation agreement, Intech was the sales partner of the Japanese producer Ibiden in several European countries where it enjoyed the exclusive right to sell Ibiden’s artificial graphite products for use in electrical discharge machining. Intech could also sell these products on a non‑exclusive basis under its own brand name in other European countries.

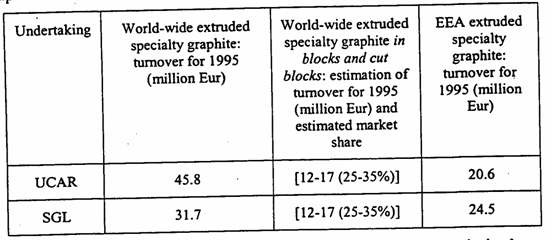

11 The main participants in the world market for extruded graphite were UCAR (40%) and SGL (30%). On the European market they accounted for two thirds of sales. The Japanese producers together held about 10% of the world market and 5% of the Community market. The proportion of sales of extruded products in the form of blocks or cut blocks (unmachined products) was 20 to 30% for UCAR and 40 to 50% for SGL.

12 In June 1997 the Commission commenced an investigation into the graphite electrodes market. The investigation led to the decision of 18 July 2001 relating to a proceeding under Article 81 of the EC Treaty and Article 53 of the EEA Agreement – Case COMP/E‑1/36.490 – Graphite electrodes (OJ 2002 L 100, p. 1). In the course of that investigation, UCAR contacted the Commission, in 1999, in order to submit a request on the basis of the Commission Notice on the non-imposition or reduction of fines in cartel cases (OJ 1996 C 207, p. 4, ‘the Leniency Notice’). The request related to alleged anti‑competitive practices in the markets for isostatic and extruded graphite.

13 On the basis of the documents submitted by UCAR, the Commission sent requests for information under Article 11 of Council Regulation No 17 of 6 February 1962 implementing Articles [81] and [82] of the Treaty (OJ English Special Edition 1959-62, p. 87, ‘Regulation No 17’) to SGL, Intech, Ibiden, Tokai and TT, requiring detailed information concerning contacts with competitors. Those companies contacted the Commission and expressed their intention to cooperate with the Commission’s investigations.

14 In the US, criminal proceedings were brought in March 2000 and in February 2001 against a subsidiary of LCL and a subsidiary of TT for participating in an illegal cartel on the specialty graphite market. The companies pleaded guilty and agreed to pay fines. In October 2001 Ibiden also pleaded guilty and paid a fine.

15 On 17 May 2002 the Commission sent a statement of objections to the addressees of the Decision. In their replies, all the companies apart from Intech EDM BV and Intech EDM AG admitted the infringement. None of them substantially contested the facts.

16 Given the similarity of the methods used by the cartel members, the fact that the two infringements concerned related products and that SGL and UCAR were involved in both cases, the Commission considered it appropriate to address the infringements in the two product markets in a single procedure.

17 The administrative procedure concluded on 17 December 2002 with the adoption of the Decision which found, first, that the applicants, TT, UCAR, LCL, Ibiden, NSC and NSCC had fixed worldwide indicative prices (target prices) on the unmachined isostatic graphite market and, second, that SGL and UCAR had committed a similar infringement, also worldwide, on the unmachined extruded graphite market.

18 With regard to the infringement on the isostatic graphite market, the Decision notes that prices were fixed and broken down by application, geographic area (Europe or the United States) and trade level (distributors/machine shops and large end-users with machining capability). The object of the cartel was to harmonise trading conditions and to exchange shipment records so as to ensure detailed monitoring of sales and the detection of deviations from cartel instructions. On some occasions, information was exchanged concerning the allocation of major customers.

19 The Decision states that collusive agreements were implemented on the isostatic graphite market by regular multilateral meetings at four levels:

– ‘top level meetings’, attended by the top executives of the companies, at which the main principles of cooperation were established;

– ‘international working level meetings’ concerning the classification of graphite blocks into different categories and the fixing of minimum prices for each category;

– ‘regional’ (European) meetings;

– ‘local’ (national) meetings concerning the Italian, German, French, British and Spanish markets.

20 The Decision states that in aiming to increase isostatic graphite prices, or to contain their fall, the cartel had an impact on the Community/EEA market. The prices fixed by the agreements and a consistent policy of price increases were applied during 1993 to 1998. Even though from 1997 the cartel members had difficulty in attaining the prices agreed at meetings, the termination of the concerted practices was immediately followed by a sharp drop in isostatic product prices.

21 With regard to the extruded graphite market, it is clear from the Decision that the two main players on the European market for such products, SGL and UCAR, admitted participation in a number of bilateral meetings dealing with that market in the period from 1993 to the end of 1996. UCAR and SGL agreed to increase extruded graphite prices on the Community/EEA market. They regularly discussed prices and the classification of products in order to avoid competing on prices. The new prices were in fact announced to customers in turn by one of the parties.

22 On the basis of the findings of fact and legal assessment in the Decision, the Commission imposed on the companies in question fines calculated in accordance with the method set out in the Guidelines on the method of setting fines imposed pursuant to Article 15(2) of Regulation No 17 and Article 65(5) of the ECSC Treaty (OJ 1998 C 9, p. 3, ‘the Guidelines’) and the Leniency Notice.

23 Under the first paragraph of Article 1 of the operative part of the Decision, the following undertakings infringed Article 81(1) EC and Article 53(1) of the EEA Agreement by participating, for the periods indicated, in a complex of agreements and concerted practices affecting the Community and EEA markets for isostatic specialty graphite:

(a) GrafTech International (UCAR), from February 1996 to May 1997;

(b) SGL, from July 1993 to February 1998;

(c) LCL, from July 1993 to February 1998;

(d) Ibiden, from July 1993 to February 1998;

(e) Tokai, from July 1993 to February 1998;

(f) TT, from July 1993 to February 1998;

(g) NSC and NSCC, jointly and severally liable, from July 1993 to February 1998;

(h) Intech EDM BV and Intech EDM AG, jointly and severally liable, from February 1994 to May 1997.

24 Under the second paragraph of the same provision, the following undertakings infringed Article 81(1) EC and Article 53(1) of the EEA Agreement by participating for the periods indicated in a complex of agreements and concerted practices affecting the Community and EEA markets for extruded specialty graphite:

– SGL, from February 1993 to November 1996;

– GrafTech International (UCAR) from February 1993 to November 1996.

25 Article 3 of the operative part imposes the following fines:

(a) GrafTech International (UCAR):

– Isostatic specialty graphite: EUR 0;

– Extruded specialty graphite: EUR 0;

(b) SGL:

– Isostatic specialty graphite: EUR 18 940 000;

– Extruded specialty graphite: EUR 8 810 000;

(c) LCL: EUR 6 970 000;

(d) Ibiden: EUR 3 580 000;

(e) Tokai: EUR 6 970 000;

(f) TT: EUR 10 790 000;

(g) NCS and NSCC, jointly and severally liable: EUR 3 580 000;

(h) Intech EDM BV and Intech EDM AG, jointly and severally liable: EUR 980 000.

26 Article 3 further orders that the fines are to be paid within three months of the date of notification of the Decision with default interest at the rate of 6.75%.

27 The Decision was sent to the applicants with a covering letter of 20 December 2002. It stated that after expiry of the period for payment specified in the Decision the Commission would take steps to recover the sums in question; however, if proceedings were commenced before the Court of First Instance the Commission would not take steps to enforce the judgment provided that interest at the rate of 4.75% was paid and a bank guarantee given.

28 The Decision was notified to the various applicants between 23 December 2002 and 8 January 2003.

Procedure

29 By separate applications lodged at the Registry of the Court of First Instance between 3 and 10 March 2003, Tokai, Intech EDM BV, Intech EDM AG and SGL brought the present actions. TT also brought an action (Case T-72/03).

30 Having heard the parties on the matter, by order of 15 June 2004 the President of the Second Chamber of the Court of First Instance ordered that the five cases be joined for the purposes of the oral procedure and judgment pursuant to Article 50 of the Rules of Procedure of the Court of First Instance. He also granted confidential treatment in respect of certain documents in the files.

31 Upon hearing the report of the Judge-Rapporteur, the Court of First Instance (Second Chamber) decided to open the oral procedure and put certain questions to the parties. The parties replied to those questions within the prescribed period.

32 The parties presented oral argument and replied to the Court’s questions at the hearing on 21 September 2004. In particular, the Commission responded at that hearing to a question which the Court put to it following a request by TT for a preparatory measure of inquiry seeking to clarify LCL’s turnover in 1997 from sales of isostatic graphite on the EEA market.

33 By letter of 23 February 2005, TT withdrew its application. By order of 10 May 2005, Case T-72/03 was removed from the register.

Forms of order sought by the parties

34 Tokai (Case T-71/03) claims that the Court should:

– annul Article 3 of the Decision in so far as it imposes a fine of EUR 6.97 million on it or, in the alternative, substantially reduce that fine;

– order the Commission to pay the costs.

35 Intech EDM BV (Case T-74/03) claims that the Court should:

– annul the Decision in so far as it concerns it;

– in the alternative, reduce the fine imposed by Article 3(h) of the Decision;

– order the Commission to pay the costs.

36 Intech EDM AG (Case T-87/03) claims that the Court should:

– annul the Decision in so far as it concerns it;

– in the alternative, reduce the fine imposed by Article 3(h) of the Decision;

– order the Commission to pay the costs.

37 SGL (Case T-91/03) claims that the Court should:

– annul the Decision in so far as it concerns it;

– in the alternative, appropriately reduce the fine imposed on it by the decision;

– order the Commission to pay the costs.

38 In all the cases, the Commission contends that the Court should:

– dismiss the action;

– order the applicant to pay the costs.

Law

39 The action brought under Case T-71/03 seeks, in substance, only to set aside or reduce the amount of the fine imposed by alleging, inter alia, infringement by the Commission of its Guidelines and Leniency Notice, without substantially contesting the facts found in the Decision. The three other actions seek, as the principal remedy, the annulment of the Decision as a whole and are based on pleas in law alleging the unlawfulness of the Decision as a whole and/or errors committed by the Commission in finding the facts said to constitute the infringement. Finally, one action (Case T-91/03) challenges the rules relating to payment of the fines.

40 It is necessary, first of all, to examine the heads of claim seeking annulment of the Decision as a whole or certain findings of fact which appear in it. Next, the Court will examine the heads of claim seeking annulment of Article 3 of the Decision or the reduction of the fines set pursuant to the Guidelines and the Leniency Notice. Finally, the Court will examine the complaints concerning the rules for payment of the fines.

A – The applications for annulment in part of Article 1 of the Decision and of certain findings of fact therein

1. The pleas in law alleging, first, an error of law in finding that Intech committed an infringement in the isostatic graphite market and, second, a failure to state reasons in that regard (Cases T-74/03 and T-87/03)

a) Summary of the Decision

41 In paragraphs 378 and 401 to 424 of the Decision, the Commission found that Intech had directly participated in the cartel in the market for isostatic graphite. It rejected Intech’s argument that its entire business in the graphite market in Europe was based on a cooperation agreement with Ibiden, that it was economically and legally dependent on Ibiden, that its personnel attended cartel meetings only on behalf of Ibiden and in accordance with Ibiden’s instructions and that Intech EDM AG was not a founding member of the cartel and did not attend ‘high-level’ or international meetings of the cartel.

42 The Commission, on the other hand, took the view that the behaviour of Intech and Ibiden in the cartel had to be assessed separately, and that they were both wholly responsible for their own part in the infringement. Intech EDM AG marketed specialty graphite in the Community and took part directly in European level cartel meetings. Intech EDM BV, the former parent company of Intech EDM AG and which held all the latter’s shares during the infringement, was the only interface between the Intech group and Ibiden for transactions relating to the specialty products market; all Intech’s European activities in relation to those products were carried out on the basis of the cooperation agreement between Intech and Ibiden.

b) Arguments of the parties

43 While admitting that they do not dispute the findings of fact in the Decision, Intech EDM BV and Intech EDM AG complain that the Commission accused them of being ‘principals’ responsible for the infringement whereas in fact they were mere ‘accessories’ to Ibiden’s infringement who could not be penalised.

44 Thus the Commission ignored the fact that, at least until 26 September 1995, the applicant was not a principal responsible for an infringement of Article 81(1) EC. Prior to that date Ibiden was not present in person at the European meetings of the cartel, but sent Mr Ankli, a director of Intech EDM AG, to represent it. As Ibiden used Intech merely as an instrument, the latter can be regarded only as an accessory to Ibiden’s infringement. However, mere complicity in the form of attending a cartel meeting is not punishable under Article 15(2) of Regulation No 17 and cannot therefore be sanctioned by a fine.

45 On the basis of a study of comparative law, Intech observes that the distinction between principal and accessory is a general principle of law. It follows that the commission of the act must be distinguished from mere complicity. The principal responsible for an infringement for the purposes of Article 15(2) of Regulation No 17 is the person who has control of events and commits the act, while the accessory, who has no control, takes part in the act of another person as an instrument or auxiliary party.

46 Moreover, an undertaking can be described as a principal in an infringement only if the restriction of competition enhances its market position and procures for it a direct economic advantage. That was precisely not the case for Intech here. The applicant had an interest in a price-reduction policy which would enable it to increase its market share.

47 Intech adds that the Commission itself found, in paragraph 515 of the Decision, that Intech obeyed Ibiden’s instructions with a view to implementing, by its presence at European and national meetings as Ibiden’s distributor, the decisions of principle made at a higher level of the cartel.

48 However, the Commission made no mention at all of Intech’s economic dependence on Ibiden. In disregarding this essential factor in the assessment of the question of complicity, the Commission failed in its duty to state reasons pursuant to Article 253 EC.

49 On this point, Intech observes that as a mere distributor with no production facilities it was economically dependent on Ibiden and, accordingly, subject to its control. It is a small enterprise, operating only at regional level and with a small turnover equal to approximately 1% of Ibiden’s. Therefore it did not have the economic strength necessary to ignore Ibiden’s instructions. The continuation of its business depended on supplies of specialty graphite from large international producers. Likewise Intech was not in a position to replace Ibiden by another producer to ensure supplies: by means of establishments, branches or sales partnerships, all the other suppliers were connected in one way or another and also organised as a group within the cartel. Consequently Intech was entirely dependent on Ibiden as its supplier.

50 Intech was also unable to avoid Ibiden’s will by refusing to attend cartel meetings and informing the Commission of the cartel. By the time the cartel had finished by being dismantled, Intech would have become insolvent long before as neither Ibiden nor any other supplier would have supplied it with specialty graphite. For the applicant, refusing to obey Ibiden’s instructions would have meant the end of its business.

51 In view of the relative economic strength of Ibiden and Intech, the latter had no choice but to apply – against its own interest – the target prices agreed on by the producers at a higher level of the cartel. In this context, Intech asks that Mr Ankli be examined as a witness in order to show that it was bound by Ibiden’s instructions. In any case, Mr Ankli did not represent Intech EDM BV, but was employed by Intech EDM AG, so that his conduct could not be attributed to the former.

52 Lastly, contrary to the Commission’s assertions, the fact that representatives of Intech EDM AG took part in several meetings of the cartel at European and national level does not preclude that company from being subject to Ibiden’s control. Intech EDM BV did not take part in any meeting of the cartel. In any event, the Commission misinterpreted several documents, in particular certain minutes of meetings organised by the cartel, on which it based its assessment of the role played by the two Intech companies.

53 While accepting that Articles 3 and 15(2)(a) of Regulation No 17 authorise the Commission to sanction only undertakings which have themselves infringed the competition rules, whereas mere ‘complicity’ is not caught by those provisions, the Commission observes that, in the present case, Intech is undoubtedly a ‘principal’ in a breach of Article 81 EC. This type of infringement consists in participation by an undertaking in a cartel, such participation being established where there is a common anti-competitive intention shared by that undertaking and one or more other undertakings.

c) Findings of the Court

54 It is clear from the case-law that, in prohibiting undertakings inter alia from entering into agreements or participating in concerted practices which may affect trade between Member States and have as their object or effect the prevention, restriction or distortion of competition within the common market, Article 81(1) EC is aimed at economic units made up of a combination of personal and physical elements which can contribute to the commission of an infringement of the kind referred to in that provision (Case T-6/89 Enichem Anic v Commission [1991] ECR II-1623, paragraph 235). An undertaking within the meaning of Article 81 EC can therefore include several subjects of the law (Case 170/83 Hydrotherm [1984] ECR 2999, paragraph 11).

55 In the present case, in subparagraph (h) of the first paragraph of Article 1 of the Decision, the Commission states that Intech EDM AG and Intech EDM BV infringed Article 81(1) EC and Article 53(1) of the EEA Agreement ‘by participating’ in the cartel operating in the isostatic specialty graphite markets and, moreover, doing so on the same basis as the other members of the cartel, including Ibiden.

56 It is therefore necessary to examine whether that specific allegation is supported by the findings in the Decision. If it is, then the pleas in law put forward by the two Intech companies must be rejected, but if it is not, then subparagraph (h) of the first paragraph of Article 1 of the Decision must be annulled and there will be no need to rule whether the Intech companies acted as accomplices.

57 It should be noted in this regard that the two applicants expressly stated in their applications that they did not challenge the findings of fact in the Decision. The present pleas in law therefore do not seek to challenge the interpretation of the unchallenged facts found by the Commission in assessing the role played by Intech EDM AG and Intech EDM BV within the cartel.

58 According to those findings (paragraphs 66 and 421), Intech EDM AG was a wholly-owned subsidiary of Intech EDM BV during the period of the infringement found to have been committed by Intech, namely from February 1994 to May 1997.

59 In those circumstances the Commission rightly referred to the case-law (paragraphs 420 and 421 of the Decision) entitling it to find that the Intech companies belonged in principle to an economic entity and therefore both of them constituted one ‘undertaking’ for the purposes of competition law (Case 107/82 AEG v Commission [1983] ECR 3151, paragraph 50, and case T-65/89 BPB Industries and British Gypsum v Commission [1993] ECR II-389, paragraph 149).

60 According to the settled case-law of the Court of Justice and the Court of First Instance (Case T-354/94 Stora Kopparbergs Bergslags v Commission [1998] ECR II-2111, paragraph 80, confirmed by Case C-286/98 P Stora Kopparbergs Bergslags v Commission [2000] ECR I-9925, paragraphs 27 to 29), the Commission can generally assume that a wholly-owned subsidiary essentially follows the instructions given to it by its parent company without needing to check whether the parent company has in fact exercised that power.

61 Before the Court, neither of the applicants has established that the subsidiary, Intech EDM AG, decided independently on its own conduct on the market rather than carrying out the instructions given to it by its parent company and such that they fall outside the definition of an ‘undertaking’. The two applications are silent on that point. It is only in their replies that the applicants asserted that the subsidiary ‘acted largely independently of its former parent company’. That assertion, unsupported by any evidence, was made out of time and so must be disregarded under Article 48(2) of the Rules of Procedure as a new and therefore inadmissible plea in law.

62 It follows that, in applying the definition of ‘undertaking’, the two Intech companies could be regarded as jointly liable for conduct alleged against them, with the acts of one being imputable to the other (see, to that effect, Case T-9/99 HFB and Others v Commission [2002] ECR II-1487, paragraphs 54, 524 and 525). That finding is not undermined by the fact that the text of the Decision sometimes departs from the proper terminology and erroneously uses the term ‘undertaking’ – for example, in paragraph 407 the Commission talks about ‘two undertakings of the Intech group’ – to describe one or other of the two Intech companies.

63 It is therefore necessary to examine which acts the Commission took into consideration and imputed reciprocally to both of the Intech companies, so as to establish their participation in the infringement found in the Decision.

64 The Commission found on this point, without being contradicted by the applicants, that Intech EDM AG took part in almost all the meetings organised by the cartel at European level (paragraph 408 of the Decision) and in several local meetings concerning the German, British, French and Italian markets (paragraphs 243, 248, 254, 261 and 267 of the Decision).

65 To the extent that the applicants submit that Intech EDM AG did not act as a ‘perpetrator’ of the infringement at those meetings, it suffices to note that according to settled case-law, where an undertaking participates, even if not actively, in meetings between undertakings with an anti-competitive object and does not publicly distance itself from what occurred at them, thus giving the impression to the other participants that it subscribes to the results of the meetings and will act in conformity with them, it may be concluded that it is participating in the cartel resulting from those meetings (Case T-7/89 Hercules Chemicals v Commission [1991] ECR II-1711, paragraph 232; Case T-12/89 Solvay v Commission [1992] ECR II-907, paragraph 98; Case T-141/89 Tréfileurope v Commission [1995] ECR II-791, paragraphs 85 and 86; and HFB and Others v Commission, paragraph 62 above, paragraph 137).

66 Intech EDM AG never publicly distanced itself from the anti-competitive content of the meetings it attended. In particular, it did not publicly demonstrate a clear wish to participate in those meetings not on its own behalf but as a mere representative of Ibiden. None of the minutes and records of those meetings discloses a public statement to that effect. Without such a statement it is not enough for the applicants to claim that some of those documents should be interpreted objectively as showing that Intech EDM AG acted in Ibiden’s sole interest, a claim which the Commission strongly disputes.

67 Moreover, the Commission was right to emphasise the extent of Intech EDM AG’s participation in the meetings of the cartel both at European and local level. The present case concerned a cartel fixing target prices broken down by geographic area, namely Europe or the United States (paragraph 98 of the Decision). Consequently, it was not sufficient to fix prices at the highest levels of the cartel, that is at ‘top-level meetings’ and ‘international working meetings’, but it was also important to ensure their actual application at regional and local levels. The fact that Intech EDM AG never took part in one of those ‘top-level meetings’ and ‘international working level meetings’ does not mean that it did not take part in the cartel.

68 It follows that the Commission was right to regard Intech EDM AG’s participation in the meetings at the European and local levels of the cartel as anti-competitive conduct. It was also entitled to impute that conduct to Intech EDM BV as it had been performed by its wholly-owned subsidiary, all the more so since activities of the Intech group in the graphite sector in Europe were carried out on the basis of a co-operation agreement that Intech EDM BV had itself entered into with Ibiden (paragraphs 67 and 421 of the Decision).

69 It should be added that objectively it was in Intech’s interest to attend the meetings organised by the cartel at European and local level. The prices fixed by the cartel were broken down by trade level, that is by distributor/machine shop, on the one hand, and large end-users with machining capability, on the other (paragraph 98 of the Decision). Intech therefore had every interest in ensuring that the fixing of those prices did not affect its profit margin. That finding is confirmed by a fax produced by the applicants themselves (Annex A23 to the applications) from which it appears that Intech was very pleased about the increase in prices for itself, but did not agree with the increase in the purchase price and found the profit margin fixed for the distributors in October 1993 to be too tight.

70 Lastly, the Commission found, without being contradicted by the applicants, that Intech undertook to charge its own customers the prices agreed by the cartel (paragraph 403 of the Decision). Furthermore, Intech’s interest in respecting the prices set by the cartel is clear from several documents referred to in the Decision, for example, a fax of 9 January 1994 from Intech to Ibiden, a letter in 1996 from Intech to Ibiden and a fax from NSCC of 27 August 1997 (paragraphs 285, 286 and footnote 533 of the Decision).

71 It follows from the foregoing that the Commission did not err in classifying the Intech group, comprised of Intech EDM AG and Intech EDM BV, as a perpetrator of an infringement of Article 81(1) EC and Article 53(1) of the EEA Agreement in the form of participation in the cartel in the isostatic specialty graphite market.

72 None of Intech’s arguments to the contrary can be upheld.

73 Intech contradicts itself when it points to its economic dependence and subordination to Ibiden’s instructions whilst at the same time pointing to its resistance to the prices set by the cartel and to the development of an independent pricing policy with the intention of capturing market share (paragraphs 51 to 57 of the applications).

74 On that last point it suffices to note that the fact that a cartel agreement is not honoured does not mean that it does not exist (Case T-141/94 Thyssen Stahl v Commission [1999] ECR II-347, paragraphs 233, 255, 256 and 341). In the present case, the infringement committed is not therefore cancelled out merely because Intech succeeded in deceiving the other members of the cartel and in using the cartel to its own advantage by not complying in full with the prices fixed (see, to that effect, Case T-308/94 Cascades v Commission [1998] ECR II-925, paragraph 230, concerning the assessment of attenuating circumstances).

75 The members of a cartel remain competitors, any one of whom may be tempted at any time to take advantage of the others’ discipline in complying with cartel prices by lowering its own prices with a view to increasing its market share, whilst maintaining relatively high prices overall. In any event, the fact that Intech did not comply in full with the prices fixed does not mean that it therefore charged the prices that it would have been able to charge in the absence of the cartel.

76 In so far as Intech points to its economic dependence on Ibiden and the pressure exerted on it by that producer, it should be noted that, according to the case-law, the existence of such factors did not eliminate any possibility for Intech to refuse to take part in the restriction of competition within the cartel. That finding also covers Intech’s specific situation. It was, as a distributor, a party to a horizontal agreement in which its supplier Ibiden also participated (see, to that effect, Case T-17/99 KE KELIT v Commission [2002] ECR II-1647, paragraphs 1 and 48 to 50, and the case-law cited).

77 Whilst Intech further submits that its economic position was so weak compared to Ibiden that any attempt to inform the Commission of the cartel and to depart from Ibiden’s instructions would necessarily have resulted in its insolvency, the Court finds that that is a mere assertion wholly unsupported by evidence. In particular, Intech does not state why it was not able to contact the Commission anonymously or to obtain confidential treatment for its information.

78 In any event, it is apparent from the figures produced by the applicants themselves that the fate of the entire Intech group did not depend solely on supplies of isostatic graphite by Ibiden. By letter of 30 November 2001 (Annex A7 to the applications), Intech EDM AG informed the Commission, in response to a request for information, that ‘about 10% of the Intech EDM companies’ overall turnover was achieved in Europe with the sale of isostatic graphite’ (1.5), whereas the worldwide overall turnover was EUR 26.8 million and that from the product in question EUR 3.4 million (1.7), or about 13%. Even if the figures in Table 1 of the Decision (paragraph 16) had been taken into account, namely EUR 15.5 million overall turnover solely for Intech EDM AG and Intech EDM BV in 2001 and EUR 2.3 million turnover for them in 1997 in respect of the product, the relevant percentage would be about 15%.

79 In those circumstances, the Commission was entitled not to include in the Decision a statement of reasons specifically addressing the economic dependence of the applicants on the Japanese producer Ibiden, without thereby infringing Article 253 EC.

80 Neither is it necessary to grant Intech’s request that a witness give evidence that the undertaking was indeed bound by Ibiden’s instructions.

81 To the extent that Intech further submits that the increases in prices by the cartel were against its own economic interests, which in fact called for the adoption of an aggressive price policy and an expansion of its market share, it suffices to note that for an undertaking to be classified as a perpetrator of an infringement it is not necessary for it to have derived any economic advantage from its participation in the cartel in question (see, to that effect, Case T-304/94 Europa Carton v Commission [1998] ECR II-869, paragraph 141).

82 Consequently, the pleas in law raised by the two Intech companies challenging their classification as ‘perpetrators’ in the infringement and the plea in law alleging a failure to state reasons cannot be upheld.

2. The pleas in law alleging an error in the finding that the cartel in the isostatic graphite market for blocks and cut blocks was worldwide (Case T-71/03)

a) Summary of the Decision

83 In paragraphs 22 to 25 and 29 of the Decision, the Commission stated that the market for isostatic graphite was worldwide. During the period in question (1993 to 1998), that market was dominated by eight global producers which controlled 80% of the world market. Transport costs and tariff barriers did not prevent producers from trading worldwide and the Japanese producers had even been able to gain more than 20% of the European market towards the end of the 1980s. The worldwide character of the market is confirmed by the structure, organisation and operation of the cartel itself.

b) Arguments of the parties

84 In connection with the pleas that the Commission was wrong in relying on its worldwide turnover, Tokai submits that the geographic market for isostatic graphite is not worldwide.

85 Tokai observes that, in its decision of 4 January 1991 (Case IV/M.0024 – Mitsubishi/UCAR), adopted pursuant to Council Regulation (EEC) No 4064/89 of 21 December 1989 on the control of concentrations between undertakings (OJ 1989 L 395, p. 1, amended by OJ 1990 L 257, p. 13), the Commission stated that the markets for graphite electrodes, carbon electrodes, graphite specialties and flexible graphite were Community-wide markets. Therefore the Commission confused the global scope of the present cartel and the geographic size of the relevant market.

86 Tokai alleges that the Commission infringed the principle of equal treatment by defining the relevant market as that for isostatic specialty graphite ‘in blocks’, when the non-European producers sold almost exclusively blocks in Europe whereas European producers sold both machined graphite and graphite in blocks.

87 The Commission denies that it confused the nature of the cartel and the size of the market. It observes that the market for specialty graphite as a whole is worldwide (paragraphs 22 to 25 of the Decision), this definition of the geographic market having already been set out in the statement of objections (paragraphs 22 to 25). Tokai did not explicitly contest this finding in its replies to the statement and produces no evidence in support of its argument.

c) Findings of the Court

88 It is necessary to recall Tokai’s express statement in its application (paragraph 31) that its action does not substantially contest the facts set out in the Decision but concerns the calculation of the fine alone. The Decision clearly finds as a fact that the cartel in the isostatic graphite market in which Tokai took part was worldwide (paragraphs 22 to 25). The real thrust of the plea in question is therefore that, in fixing the fine imposed on Tokai, the Commission disregarded the geographically-restricted role allegedly played by the applicant.

89 That conclusion is not contradicted by Tokai’s reference to the Commission’s decision of 4 January 1991 (see paragraph 85 above) in which the Commission found that, in a matter concerning a concentration between undertakings, there was a Community market for specialty graphite. It suffices to note in that connection that that decision was adopted in a context different from that in the present case and that it predates both the Commission’s investigation in this case and the period of the infringement found in the Decision. It was precisely the detection, from 1999, of the cartel in which Tokai took part which enabled the Commission to find that the cartel members had fixed worldwide prices for specialty graphite. The reference to the 1991 decision is therefore otiose (see, mutatis mutandis, Joined Cases T-236/01, T-239/01, T-244/01 to T-246/01, T‑251/01 and T-252/01 Tokai Carbonand Others v Commission [1994] ECR II‑0000, hereinafter ‘Graphite electrodes’, paragraph 66).

90 In so far as Tokai alleges that the Commission erred in defining the worldwide market as being that for isostatic graphite in blocks and cut blocks, its plea is manifestly irrelevant. It is not the Commission which arbitrarily chose the relevant market but the members of the cartel in which Tokai participated who deliberately concentrated their anti-competitive conduct on unmachined products, that is isostatic graphite in blocks and cut blocks.

91 It follows from the foregoing that Tokai’s pleas directed against the finding in the Decision that the market for isostatic graphite in blocks and cut blocks was worldwide must be rejected.

92 The examination of the first group of pleas in law has revealed that none of the arguments raised by the applicants justifies annulment of the factual findings in the Decision. Consequently, the claim for annulment of part of Article 1 of the Decision must be rejected.

93 The same applies to SGL’s claim for annulment of the Decision, which alleges that the Commission committed a basic error in respect of the basis for calculating the fines and concludes that that infringement of essential procedural requirements requires that the Decision be annulled on that ground alone (paragraph 70 of the application). It is plain that the Decision cannot be annulled in its entirety, including the findings of fact and the legal assessment of the infringement committed by SGL, merely because of an error vitiating the calculation of the fine imposed on the applicant. Such an error could clearly affect only the imposition of the fine per se. Consequently, that claim by SGL must be rejected and the pleas in law raised by it in that context will be examined below in the context of the pleas in law seeking annulment of Article 3 of the Decision or the reduction of the amount of the fines.

94 Accordingly, the subsequent examination of the form of order sought and the pleas in law directed to the setting of the fines will take account of the findings of fact in the Decision with the exception of those concerning the particular figures used by the Commission for the purpose of dividing the members of the cartel into categories in order to set the starting amounts of the fines.

B – The pleas in law that the fines be annulled or their amount reduced

1. The pleas in law alleging an infringement of the principle of the non-cumulation of penalties and of the Commission’s duty to take account of penalties previously imposed and a failure to state reasons in that regard (Case T-71/03 and Case T-91/03)

a) Summary of the Decision

95 In paragraphs 545 to 550 of the Decision, the Commission rejected SGL’s argument that it should have taken account of the penalties which were imposed on SGL for the same conduct in the United States. According to the Commission, the fines imposed elsewhere, including in the United States, have no bearing on those to be imposed for infringement of the Community competition rules.

96 The Commission also rejected SGL’s argument that the agreements in question in the present case were closely linked to those which formed the subject-matter of the case giving rise to the Graphite electrodes judgment, in which the Commission had already imposed fines, and new penalties could not therefore be imposed in the Community.

97 According to the Commission, the present procedure concerned agreements which are clearly distinguishable from the agreements in the case giving rise to the Graphite electrodes judgment. That justified the two agreements being treated as separate infringements which might result in separate fines being imposed. For the same reason, the Commission rejected SGL’s argument that it had not taken part in two separate cartels, namely for isostatic graphite and for extruded graphite.

b) Arguments of the parties

98 Tokai complains that the Commission infringed the principle of ne bis in idem and exceeded its powers by setting its fine according to its worldwide market shares and worldwide turnover. In so doing, the Commission took account of the relative size of the undertakings on markets other than the EEA and, consequently, their impact on competition in those markets. Such effects outside the EEA fall within the jurisdiction of other competition authorities and Tokai should be punished only for its impact on competition in the EEA.

99 Tokai adds that it was the subject of an investigation in the United States concerning the same matters as those covered by the Decision. As its request for immunity was accepted by the American authorities, Tokai was not fined. It is not for the Commission to call into question that decision of the American authorities. Consequently any fine imposed by the Commission which takes account of the effects of the cartel in the United States would amount to a double penalty for Tokai.

100 SGL submits that, by refusing to deduct from the fines imposed by the Decision the amount of the fines already imposed in the United States, the Commission breached the rule against the cumulation of penalties. That rule is based on the principles of equity and proportionality anchored in the constitutional law of the Community. It was confirmed by Article 50 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union, proclaimed at Nice on 7 December 2000 (OJ 2000 C 364, p. 1) and by Articles 54 to 58 of the Convention implementing the Schengen Agreement of 14 June 1985, between the Governments of the States of the Benelux Economic Union, the Federal Republic of Germany and the French Republic on the gradual abolition of checks at their common borders (OJ 2000 L 239, p. 19) signed in Schengen (Luxembourg) on 19 June 2000. The rule against double jeopardy is also enshrined in Article 4 of Protocol No 7 of the European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms (‘ECHR’) signed in Rome on 4 November 1950, as interpreted by the judgment of 29 May 2001 of the European Court of Human Rights, Fischer v Austria.

101 SGL observes that this general principle has been recognised by several judgments of the Court of Justice and the Court of First Instance. SGL calls into question the recent judgment in Case T-224/00 Archer Daniels Midland and Archer Daniels Midland Ingredients v Commission [2003] ECR II-2597 inasmuch as it is to be interpreted as meaning that the Court finds that the principle of ne bis in idem is not applicable in the case of a first prosecution by non-member States.

102 SGL submits that the matters found in the Decision have already been the subject of criminal and civil judgments in the United States. The principle of ne bis in idem prevents the Commission from bringing proceedings again in respect of the same conduct. SGL adds that a plea bargain was signed on 3 May 1999 by the United States and itself which covers all the competition law offences relating to the production and sale of graphite during the period in question ‘in the United States and elsewhere’ and which provides for a fine of USD 135 million. This penalty also covers specialty graphite. In this connection, SGL proposes that several witnesses domiciled in the United States be examined.

103 According to the Decision, the most important of the cartel agreements restricting competition were formulated in a uniform manner on a worldwide basis at international meetings and were implemented at the regional and local levels both in North America and in Europe. The American authorities imposed fines on the entire cartel, namely both on the cartels on an international basis and on their local application in North America. In those circumstances, when pursuing SGL a second time, the Commission ought to have taken account of the penalties already imposed.

104 Even if the Commission had been entitled to impose a further fine for the conduct alleged against SGL in the Decision, a general principle of equity nevertheless required account to be taken, in calculating the new fine, of the penalties imposed by the Commission’s decision concerning graphite electrodes and by the American authorities. The Commission was therefore limited, by virtue of the principle of proportionality, to imposing a token fine on SGL.

105 That requirement of equity means that, in the case of parallel proceedings, whether within the Community or in relation to non-member countries, the penalty which was first imposed should be taken into account in the second penalty. Penalties for offences under cartel law always have a deterrent function with the aim of protecting free competition. From that viewpoint, the objective of and legal interest protected by Community cartel law and American cartel law are identical as they both aim to protect free and open competition.

106 In this context SGL refers to the Agreement between the European Communities and the Government of the United States of America on the application of positive comity principles in the enforcement of their competition laws (OJ 1998 L 173, p. 28, ‘the comity agreement’). SGL submits that this agreement brings together, under the definition of ‘competition law’ or ‘competition rules’, Articles 81 and 82 EC as well as sections 1 to 7 of the Sherman Act and sections 17 to 27 of the Clayton Act. The division of tasks between the Community authorities and the American authorities in connection with the prevention of international infringements of cartel law which have concentrated geographic effects can only be envisaged if, on both sides, the elements of the offences and objectives of the proceedings are consistent and if the matters in question are identical. If the powers of the Community and the American authorities did not overlap, there would not have been an administrative agreement on the alternative intervention of the investigating authorities.

107 SGL adds that the Decision is contrary to the rule against the cumulation of penalties also within the European Union, given that the Commission has imposed fines on SGL, in separate decisions, first, for an offence in relation to graphite electrodes and, now, for offences concerning specialty graphite (isostatic and extruded graphite). However, the procedure relating to graphite electrodes and that to specialty graphite were based on the same conduct, so that the Commission penalised the same conduct twice. The agreements concerning graphite electrodes and specialty graphite had the same objective, were adopted and implemented in the same way and had the same grounds.

108 The separation of the two procedures was all the more artificial because, in the Decision, the Commission imposed a fine on two cartels for different products, namely isostatic graphite and extruded graphite, considering that, in view of the similarity of the methods used and the fact that the two offences concerned related products, the agreements relating to the two products should be examined in a single procedure (paragraph 346 of the Decision). The same reasoning should apply to the relationship between the conduct which is the subject of the present proceedings and that which was the subject of the proceedings relating to graphite electrodes.

109 Referring to the legal concept of a continuous infringement, SGL states that the infringements in the sector of specialty graphite and that of graphite electrodes constitute a single substantive element, so that they should have been punished only once. Those infringements were directed against the same legal interest (competition in the EEA) and were committed in the same way: the market for graphite electrodes and the market for specialty graphite were closely connected and similar by reason of their structure and the main economic operators active in those markets. In particular, the agreements relating to graphite electrodes and those relating to specialty graphite followed the same model and were based on the global plan established by SGL, UCAR and Tokai for extending the existing cartel for graphite electrodes to specialty graphite.

110 Finally, if the Commission wishes to impose separate penalties, it is necessary for it to be able to exclude both the application of the notions of the theoretical co-existence of infringements and also of the continuous infringement. However, in the present case it did not even address the submission concerning a continuous infringement. Consequently the Commission did not fulfil its obligation under Article 253 EC to state reasons in the present proceedings.

111 The Commission contends that the Court should reject those pleas in law.

c) Findings of the Court

112 As regards the pleas in law alleging unlawful cumulation of penalties imposed by the Commission on the one hand and the US authorities on the other, it is settled case-law that where the facts on which two offences are based arise out of the same set of agreements but they nevertheless differ as regards both their object and their geographical scope, the principle of ne bis in idem does not apply (see Case 7/72 Boehringer v Commission [1972] ECR 1281, paragraphs 3 and 4, and Graphite electrodes, paragraph 133, and the case-law cited).

113 In the present case, under the principle of territoriality, there are no conflicts in the exercise by the Commission and by the US authorities of their power to impose fines on undertakings which infringe the competition rules of the EEA and of the United States (see, to that effect, Graphite electrodes, paragraphs 133 to 148).

114 In those circumstances, there is no need to consider SGL’s assertion that the penalties imposed on it in the United States for its participation in the graphite electrodes cartel also concerned specialty graphite or to hear on this point from the witnesses named by SGL. Even if that assertion were correct, the US penalties did not preclude the Commission from imposing a fine on SGL for its participation in the cartel in the specialty graphite market.

115 It follows that the allegation of an infringement of the principle of ne bis in idem must also be rejected in so far as Tokai claims that the Commission took into account its worldwide turnover and market share (see, to that effect, Graphite electrodes, paragraph 138), all the more so since those figures in respect of the worldwide market were only used by the Commission to distinguish the relative impact of the undertakings implicated in the cartel (see paragraphs 167 to 170 below).

116 That conclusion is not undermined by the comity agreement (see paragraph 106 above). In so far as SGL claims that that agreement entails the application of the principle of ne bis in idem in relations between the United States and the Community, the applicant’s argument is based on an erroneous reading of that agreement. It is clear from Article I(2)(b) and Article III of that agreement that the legal interests protected by the Community authorities and the US authorities are not the same and that the purpose of the agreement is not the principle of ne bis in idem but solely to enable the authorities of one of the contracting parties to take advantage of the practical effects of a procedure initiated by the authorities of the other.

117 By its plea in law alleging unlawful cumulation of penalties imposed by the Commission within the Community itself, SGL claims that by imposing on it a fine in respect of graphite electrodes and then fines in respect of specialty graphites, the Commission penalised it for the same facts twice. It claims that the agreements on graphite electrodes and on specialty graphite constituted a continuous infringement based on an overall plan in which the existing cartel for graphite electrodes was extended to specialty graphite. The separation of the two proceedings is claimed to be all the more artificial since, in the Decision, after the same proceeding, the Commission penalised two cartels in respect of different products, namely isostatic graphite and extruded graphite.

118 It should be noted in this connection that the Commission was entitled to impose on SGL three separate fines, each within the limits imposed by Article 15(2) of Regulation No 17, provided that the applicant had committed three separate infringements of Article 81(1) EC.

119 As is clear from paragraphs 4 and 5 of the contested decision in the case giving rise to the Graphite electrodes judgment (see paragraph 12 above) and paragraphs 4 to 12 of the Decision, graphite electrodes and specialty graphite belonged to distinct markets. As SGL expressly confirmed in reply to a request for information (Annex 14 to the application in Case T-91/03), the properties, price and applications of isostatic graphite and extruded graphite are very different (paragraph 5, footnote 5 and paragraphs 10 to 12 and 19 to 21 of the Decision).

120 Furthermore, the three cartels did not have the same members. LCL, Ibiden, TT, NSC/NSCC and Intech did not take part in the graphite electrodes cartel, whereas VAW, SDK, Nippon, SEC and C/G – which were members of that cartel – did not take part in the isostatic graphite cartel. Only SGL and UCAR were members of both specialty graphite cartels, since the other participants in the isostatic graphite cartel were not participants in the extruded graphite cartel. SGL and UCAR were therefore the only undertakings who were party to all three cartels.

121 Lastly, contrary to SGL’s assertions, the cartel in the specialty graphite market was not simply an ‘extension’ of the graphite electrodes cartel.

122 In addition to a price-fixing system, the graphite electrodes cartel included a very strict system of market sharing based on the principle of ‘home producer’ under which ‘non-home’ producers had to abandon all aggressive competition in the territories reserved to other producers and withdraw from those territories: UCAR was responsible for the United States and certain parts of Europe, SGL for the rest of Europe, and four Japanese undertakings were responsible for Japan and certain parts of the Far East (Graphite electrodes, paragraphs 12 and 13).

123 By contrast, there was no such market sharing in the cartel in the market for specialty graphite, notwithstanding certain, apparently unsuccessful, attempts to share customers (see, in particular, paragraphs 171, 174, 178 to 180, 192, 203, 292 and 295 of the Decision). On the contrary, transport costs and tariff barriers did not prevent producers from trading on a worldwide scale, as is demonstrated by the fact that the Japanese producers, although not having any production sites outside Japan, were able to sell their products in Europe and obtain a market share of more than 20% (paragraph 24 of the Decision).

124 It is therefore on objective grounds that the Commission initiated separate procedures in respect of the markets for graphite electrodes and specialty graphite, found three separate infringements and imposed three separate fines.

125 That finding is not undermined by the fact that the Decision penalises two cartels at the same time (isostatic graphite and extruded graphite) on the ground that they concerned neighbouring products (paragraph 347). As those cartels concerned neighbouring products the Commission had no choice but to dispense with dual proceedings. However, the members of each cartel received specific fines, one in respect of the isostatic graphite market and the other in respect of that for extruded graphite, as the fact that the products were neighbouring products had no bearing on the fines.

126 As regards the plea alleging failure to state reasons, in that the Commission failed to address the argument that the infringement was continuous, it should be noted that, according to settled case-law, the statement of reasons must disclose in a clear and unequivocal fashion the reasoning followed by the institution which adopted the measure in question in such a way as to enable the persons concerned to ascertain the reasons for the measure so as to defend their rights and to enable the Community judicature to carry out its review (Graphite electrodes, paragraph 149, and Joined Cases T-12/99 and T-63/99 UK Coal v Commission [2001] ECR II-2153, paragraph 196).

127 In the present case, SGL could easily infer from the Commission’s conduct that in the present case it did not intend to apply the concept of a continuous infringement. In the Decision, it described in detail the various specialty graphites, but not graphite electrodes, which were in fact the subject of an earlier and separate decision. That clearly sufficed to inform SGL that it was being fined several times, which the Commission could not have done if it had found that SGL committed one single infringement. Furthermore, SGL was perfectly able to defend its view that its involvement in the various cartels should be treated as a continuous infringement.

128 It follows from the foregoing that the pleas in law alleging an infringement of the principle of non-cumulation of penalties and the Commission’s duty to take account of penalties previously imposed and a failure to state reasons in that regard must all be rejected.

129 Consequently, the Court must also reject the plea that undue weight was given to the gravity of the infringement alleged against SGL in that the Commission set three separate starting amounts, in respect of graphite electrodes, isostatic graphite and extruded graphite, even though the procedures in the three cases were based on the same facts and the infringements penalised are a single act for the purposes of Article 15 of Regulation No 17. As set out above, the Commission was entitled to find that there were three separate infringements which could be penalised by three separate fines.

2. The pleas in law alleging an infringement of the rights of the defence (Case T‑91/03)

a) Arguments of the parties

130 SGL complains first that the Commission infringed its right to be heard and its rights of defence. First, the Commission found in the statement of objections that LCL and SGL should be regarded as ringleaders of the cartel in the isostatic graphite market, so that SGL was justified in assuming that its participation and that of LCL had been assessed by the Commission in such a way as to lead to the conclusion that the contribution to the cartel of the two companies had been comparable. However, in the Decision the Commission altered its assessment and found that SGL was the sole leader and instigator of the infringement. The resulting 50% increase in SGL’s fine is therefore a new and independent objection on which the applicant has not had an opportunity to be heard. With this totally unforeseeable change in its assessment of the facts, the Commission made an important distinction between LCL and SGL.

131 SGL states that, in view of the provisional assessment in the statement of objections, it saw no reason to object to an identical evaluation of the contributions of LCL and SGL in the present case. The fundamentally balanced presentation in the statement of objections of their respective contributions to the offence did not, in the absence of a ringleader, suggest any increase, or at most suggested the same level of increase in the starting amount. On the other hand, the applicant would certainly have strongly disputed an assessment in the statement of objections which described SGL alone as the leader of the cartel and revealed that a substantial increase of 50% would be added to the proposed fine on SGL only.

132 Second, the Commission entrusted the present case to officials who did not have a sufficient command of German and were therefore unable, from the point of view of language, to make a proper assessment of SGL’s arguments. In the Decision, the Commission took no account whatsoever of SGL’s reply of 25 July 2002 to the statement of objections. In that reply, SGL clearly drew the Commission’s attention to the fact that the statement contained erroneous figures and submitted correct figures. The Decision, however, repeated the figures originally contained in the statement and made no comment on the corrected figures supplied by the applicant.

133 Third, to calculate the basic amount of the fines by reference to the turnover and market shares of the companies involved, the Commission took 1997 as the reference year in the Decision. In the statement of objections, on the other hand, the figures for 1998 were taken as the basis. The use of different reference years deprived the applicant of the possibility of commenting on the figures ultimately adopted in the Decision against the applicant. The statement of objections and the decision should not refer to different facts (Case T-213/00 CMA CGM and Others v Commission [2003] ECR II-913, paragraph 109). The Commission ought to have drawn attention to its change of approach (Joined Cases T-191/98 and T‑212/98 to T‑214/98 Atlantic Container Line and Others v Commission [2003] ECR II-3275, paragraphs 162 to 168, 170 to 172 and 188).

134 The Commission contends that SGL’s complaints should be rejected.

135 It asserts that all the correspondence between its services and the applicant was in German. Only the third request for information was in English. However, SGL did not request a translation and replied in German.

136 Regarding the role of SGL and LCL in the isostatic graphite cartel, the Commission considers that the fact that LCL was not regarded as another leader of the cartel in no way influenced the decision concerning the applicant. The Commission based its conclusions in the Decision on the same facts as in the statement of objections. It merely found that the role of leader alleged against LCL in the statement of objections was not sufficiently proven (paragraph 487 of the Decision).

137 Lastly, the Commission denies that it used turnover figures for different years (1998 and 1997 respectively) in the statement of objections and in the Decision. In the statement of objections, the Commission pointed out that it would consider whether the addressees should be fined. Consequently the addressees were in a position to arrange their defence not only against a finding of an infringement, but also against the imposition of fines (HFBand Others v Commission, paragraph 62 above, paragraph 313 et seq.).

b) Findings of the Court

138 According to settled case-law, the statement of objections must be couched in terms which, even if succinct, are sufficiently clear to enable the parties concerned properly to identify the conduct complained of by the Commission and to enable them properly to defend themselves, before the Commission adopts a final decision. That obligation is satisfied where the decision does not allege that the persons concerned have committed infringements other than those referred to in the statement of objections and only takes into consideration facts on which the persons concerned have had the opportunity of making known their views (see CMA CGM and Others v Commission, paragraph 133 above, paragraph 109 and the case-law cited).

139 More specifically, as regards the calculation of the fines, it is also settled case-law that the Commission satisfies its obligation to respect the right of undertakings to be heard where it expressly states, in the statement of objections, that it is going to consider whether it is appropriate to impose fines on the undertakings and also indicates the main factual and legal criteria capable of giving rise to a fine, such as the gravity and the duration of the alleged infringement and the fact that the infringement was committed ‘intentionally or negligently’. In doing so it gives them the necessary details to enable them to defend themselves not merely against the finding of an infringement but also against the imposition of fines (Joined Cases 100/80 to 103/80 Musique diffusion française and Others v Commission [1983] ECR 1825, paragraph 21, and Case T-23/99 LR AF 1998 v Commission [2002] ECR II-1705, paragraph 199, and the case-law cited).

140 Thus, so far as concerns the determination of the amount of the fines, the rights of defence of the undertakings are guaranteed before the Commission through their opportunity to make submissions on the duration, the gravity and the forseeability of the anti-competitive nature of the infringement (Case T-83/91 Tetra Pak v Commission [1994] ECR II-755, paragraph 235; HFB and Others v Commission, paragraph 62 above, paragraph 312, and LR AF 1998 v Commission, paragraph 139 above, paragraph 200).

141 By contrast, where it has indicated the elements of fact and of law on which it would base its calculation of the fines, the Commission is under no obligation to explain the way in which it would use each of those elements in determining the level of the fine. To give indications as regards the level of the fines envisaged, before the undertakings have been invited to submit their observations on the allegations against them, would be to anticipate the Commission’s decision and would thus be inappropriate (see LR AF 1998 v Commission, paragraph 139 above, paragraph 206 and the case-law cited).

142 It is in the light of the case-law set out above that SGL’s pleas in law must be examined.

143 First of all, it should be noted in this regard that SGL does not claim that the Decision contains complaints as to its unlawful participation in the cartels in question which, although not found in the statement of objections, were made against it in Article 1 of the Decision.

144 The Commission clearly stated in paragraphs 402 to 411 of the statement of objections that it was going to impose on the undertakings concerned fines which would take account, first, of the gravity, duration, nature and specific effects of the infringement and the size of the relevant geographic market, second, of any aggravating or attenuating circumstances in respect of each undertaking and, third, of the need to set fines at an appropriate level to ensure a sufficient dissuasive effect.

145 Thus, the Commission indicated the principal elements of fact and law capable of giving rise to the imposition of a fine on SGL and stated that it would determine that fine in particular on the basis of the gravity and duration of the infringement.

146 Respect for SGL’s rights of defence did not require the Commission to indicate more precisely in the statement of objections the way in which it would use each of those elements in setting the fine.

147 That finding is reinforced by the fact that, when SGL became aware of the statement of objections in May 2002, it was aware of the Guidelines, published by the Commission in 1998 and which had already been held by the Court of First Instance on 20 March 2002 (LR AF 1998 v Commission, paragraph 139 above, paragraphs 231 to 237) not to exceed the legal limits of penalties as defined by Article 15(2) of Regulation No 17. It therefore had to expect that the calculation of any fine would take account of the matters set out in detail in the guidelines that were expressly intended to ‘ensure the transparency and impartiality’ of the calculation of the fines (see the first paragraph of the Guidelines).

148 As regards SGL’s pleas in law, the Court notes that the statement of objections alleged that SGL and LCL played the role of leader or instigator in the cartel (paragraph 410). That same allegation was taken into account in respect of SGL as an aggravating circumstance in the Decision (paragraphs 485 to 488). Contrary to SGL’s argument, it cannot therefore be regarded as a new complaint against it.

149 Neither has SGL succeeded in demonstrating that the failure to take LCL into account as the second ringleader of the cartel could influence the calculation of its own fine. There is nothing in the Decision to suggest that SGL’s liability as ringleader of the cartel was increased by the attribution to it of part of the joint leadership role originally attributed by the Commission to LCL.

150 In any event it is not in dispute that in its reply to the statement of objections SGL did not challenge the Commission’s provisional assessment that SGL and LCL should be regarded as ringleaders of the cartel. Since SGL was previously implicated in at least one other completed cartel investigation, it was aware that the statement of objections was purely provisional in that each undertaking to which it was addressed had an opportunity to submit its observations and influence the Commission’s preliminary findings and that this might induce it to amend its assessment and abandon in the final decision one or other of the complaints which it had initially intended to uphold against that undertaking.

151 SGL could not therefore reasonably rule out that LCL would challenge its provisional classification as ringleader and that the Commission would uphold that finding. Since it did not simultaneously deny that it was a ringleader, the applicant had therefore to expect that the Commission might find in the Decision that there was only one leader of the cartel, namely SGL, and increase its basic amount by 50%, as it had already done in paragraph 356 of Commission Decision 2001/418/EC of 7 June 2000 relating to a proceeding pursuant to Article 81 of the EC Treaty and Article 53 of the EEA Agreement (Case COMP/36.545/F3 — Amino Acids) (OJ 2001 L 152, p. 24, ‘the Lysine decision’).

152 As for the reference year used in the Decision for the purposes of calculating fines, that is the last whole calendar year of the infringement, SGL has not stated how its rights of the defence could have been infringed by the fact that the Decision adopted the relevant figures for 1997, whereas the statement of objections used the 1998 figures. Both the 1997 and 1998 figures were provided by SGL itself before the statement of objections was drawn up. The applicant was therefore able to make any comment it considered useful in respect of those figures.

153 In any event, SGL could expect that the reference year finally adopted might differ from that provisionally indicated in the statement of objections as the choice of that year depended on the precise duration of the infringement. That duration was finally established, on the basis of the replies to the statement of objections, only in the Decision.

154 Lastly, the allegation that the Commission entrusted SGL’s ‘German file’ to officials who did not have sufficient command of German is a pure supposition unsupported by any reliable evidence. In any event, whilst it is true that the Decision does not take account of the applicant’s observations on the allegedly inaccurate figures in the statement of objections and reproduced in that form in the Decision, that omission still does not infringe SGL’s rights of defence. If the Court found that the Commission, contrary to SGL’s observations, had relied on accurate figures, the Commission would have been right to discount those observations. On the other hand, if SGL succeeded in showing that the figures were indeed inaccurate, the Decision would be vitiated by a substantive error and would have to be annulled in that respect.

155 It follows from the foregoing that all of the pleas in law alleging an infringement of the rights of the defence must be rejected.

3. The pleas in law alleging an infringement of the Guidelines, the unlawfulness of the Guidelines and a failure to state reasons in that regard

a) The legal framework within which the fines were imposed on the applicants and the applicability of the Guidelines (T-91/03)

156 Article 15(2) of Regulation No 17 states that ‘the Commission may by decision impose on undertakings … fines of from [EUR] 1 000 to 1 000 000 …, or a sum in excess thereof but not exceeding 10% of the turnover in the preceding business year of each of the undertakings participating in the infringement where, either intentionally or negligently … they infringe Article [81](1) … of the Treaty’. That provision also states that ‘in fixing the amount of the fine, regard shall be had both to the gravity and to the duration of the infringement’.