JUDGMENT OF THE GENERAL COURT (Seventh Chamber)

25 September 2014 (*)

(Community trade mark — Invalidity proceedings — Three-dimensional Community trade mark — Shape of two packaged goblets — Absolute ground for refusal — Lack of distinctive character — Lack of distinctive character acquired through use — Article 7(1)(b) and 7(3) of Regulation (EC) No 207/2009)

In Case T‑474/12,

Giorgio Giorgis, residing in Milan (Italy), represented by I. Prado and A. Tornato, lawyers,

applicant,

v

Office for Harmonisation in the Internal Market (Trade Marks and Designs) (OHIM), represented by I. Harrington, acting as Agent,

defendant,

the other party to the proceedings before the Board of Appeal of OHIM, intervener before the General Court, being

Comigel SAS, established in Saint-Julien-lès-Metz (France), represented by S. Guerlain, J. Armengaud and C. Mateu, lawyers,

ACTION brought against the decision of the First Board of Appeal of OHIM of 26 July 2012 (Case R 1301/2011-1) concerning invalidity proceedings between Comigel SAS and Mr Giorgio Giorgis,

THE GENERAL COURT (Seventh Chamber),

composed of M. van der Woude, President, I. Wiszniewska-Białecka (Rapporteur) and I. Ulloa Rubio, Judges,

Registrar: E. Coulon,

having regard to the application lodged at the Court Registry on 31 October 2012,

having regard to the response of OHIM lodged at the Court Registry on 7 February 2013,

having regard to the response of the intervener lodged at the Court Registry on 5 February 2013,

having regard to the reply lodged at the Court Registry on 24 May 2013,

having regard to the fact that no application for a hearing was submitted by the parties within the period of one month from notification of closure of the written procedure, and having therefore decided, acting upon a report of the JudgeRapporteur, to give a ruling without an oral procedure, pursuant to Article 135a of the Rules of Procedure of the General Court,

gives the following

Judgment

Background to the dispute

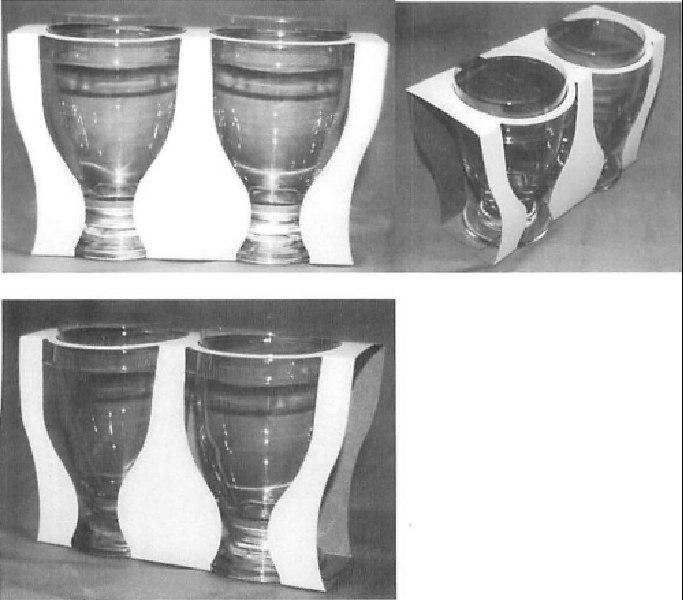

1 On 11 November 2009, the applicant, Mr Giorgio Giorgis, was granted registration of the three-dimensional Community trade mark reproduced below (‘the contested mark’), under No 8132681, by the Office for Harmonisation in the Internal Market (Trade Marks and Designs) (OHIM) pursuant to Council Regulation (EC) No 207/2009 of 26 February 2009 on the Community trade mark (OJ 2009 L 78, p. 1):

2 The goods in respect of which that mark was registered are in Class 30 of the Nice Agreement concerning the International Classification of Goods and Services for the Purposes of the Registration of Marks of 15 June 1957, as revised and amended, and correspond to the following description: ‘Ice, flavoured ices, mixed sorbets, ice sorbets, ice creams, ice-cream drinks, ice-cream goods, ice-cream desserts, semi-frozen desserts, desserts, frozen yoghurt, pastry’.

3 On 19 January 2010, the intervener, Comigel SAS, filed an application for a declaration that the contested mark was invalid on the basis of Article 52(1)(a) of Regulation No 207/2009, read in conjunction with Article 7(1)(b) and (d) of that regulation.

4 By decision of 21 April 2011, the Cancellation Division of OHIM granted the application for a declaration of invalidity and declared the contested mark to be invalid for all the goods in question on the basis of Article 7(1)(b) of Regulation No 207/2009, read in conjunction with Article 52(1)(a) of that regulation. In addition, it rejected the applicant’s argument that the contested mark had acquired distinctive character through use in accordance with Article 7(3) of Regulation No 207/2009.

5 On 16 June 2011, the applicant filed a notice of appeal with OHIM against the decision of the Cancellation Division.

6 By decision of 26 July 2012 (‘the contested decision’), the First Board of Appeal of OHIM dismissed the appeal. It confirmed the conclusions of the Cancellation Division that, first, the contested mark was devoid of any distinctive character within the meaning of Article 7(1)(b) of Regulation No 207/2009 and, secondly, the applicant had failed to demonstrate that the contested mark had acquired distinctive character through use, for the purposes of Article 7(3) and Article 52(2) of that regulation.

Forms of order sought

7 The applicant claims that the Court should:

– annul the contested decision;

– order OHIM to pay the costs.

8 OHIM and the intervener contend that the Court should:

– dismiss the action;

– order the applicant to pay the costs.

Law

9 In support of his action, the applicant raises two pleas in law, alleging, respectively, infringement of Article 7(1)(b) of Regulation No 207/2009 and infringement of Article 7(3) of that regulation.

First plea in law, alleging infringement of Article 7(1)(b) of Regulation No 207/2009

10 The applicant alleges that the Board of Appeal assessed the distinctive character of the contested mark incorrectly and thereby infringed Article 7(1)(b) of Regulation No 207/2009.

11 Under Article 52(l)(a) of Regulation No 207/2009, a Community trade mark is to be declared invalid on application to OHIM in the case where that mark has been registered contrary to the provisions of Article 7 of that regulation. In this regard, Article 7(1)(b) of Regulation No 207/2009 provides that trade marks which are devoid of any distinctive character are not to be registered.

12 According to settled case-law, in order for a trade mark to possess distinctive character for the purposes of Article 7(1)(b) of Regulation No 207/2009, it must serve to identify the goods in respect of which registration is sought as originating from a particular undertaking, and thus to distinguish those goods from those of other undertakings (see Joined Cases C‑344/10 P and C‑345/10 P Freixenet v OHIM [2011] ECR I‑10205, paragraph 42 and the case-law cited).

13 The distinctive character of a trade mark must be assessed, first, by reference to the goods or services in respect of which registration has been sought and, second, by reference to the relevant public’s perception of the mark, the relevant public consisting of average consumers of those goods or services, who are reasonably well informed and reasonably observant and circumspect (see Joined Cases C‑456/01 P and C‑457/01 P Henkel v OHIM [2004] ECR I‑5089, paragraph 35 and the case-law cited).

14 In the present case, the Board of Appeal found that the goods in question are food products that are generally pre-packed at the time they reach commercial outlets and that, in the case of goods that are marketed pre-packed, the level of attention of consumers as to the appearance of the goods is not particularly high.

15 The applicant alleges that the Board of Appeal assessed the relevant public’s level of attention incorrectly. He argues that the average consumer of ice creams displays a high level of attention, given that his choice is made on the basis of various factors, such as the flavour of the ice cream, the way in which it is consumed, the various kinds of ice creams and the possible presence of certain ingredients.

16 In this connection, suffice it to observe that the goods covered by the contested mark are everyday consumer food products, which are aimed at all consumers. Accordingly, the distinctive character of the contested mark is to be assessed by taking into account the presumed expectation of the average consumer, who is reasonably well informed and reasonably observant and circumspect (see, to that effect, Case T‑129/04 Develey v OHIM (Shape of a plastic bottle) [2006] ECR II‑811, paragraph 46 and the case-law cited, and judgment of 12 December 2013 in Case T‑156/12 Sweet Tec v OHIM (Oval shape), not published in the ECR, paragraph 14).

17 Contrary to what the applicant claims, the fact that the average consumer chooses an ice cream on the basis of his tastes and preferences is not such as to confer on him a high level of attention. Ice creams are inexpensive, everyday consumer goods, generally sold in supermarkets, the purchase of which is not preceded by a lengthy period of reflection, and in respect of which there are no grounds for taking the view that the consumer will display a high level of attention at the time of purchase. Furthermore, the fact that the consumer chooses goods on the basis of his tastes is obvious in the case of mass-consumption food products, in respect of which, according to the case-law cited in paragraph 16 above, the consumer’s level of attention is not regarded as being high.

18 The Board of Appeal therefore acted correctly in holding that the relevant public is made up of the average consumer, who is reasonably well informed and reasonably observant and circumspect, in any country of the European Union, and who does not display a particularly high level of attention.

19 According to settled case-law, the criteria for assessing the distinctive character of a three-dimensional trade mark consisting of the appearance of the product itself are no different from those applicable to other categories of trade mark. However, when those criteria are applied, the perception of the relevant public is not necessarily the same in relation to a three-dimensional mark consisting of the appearance of the product itself as it is in relation to a word or figurative mark consisting of a sign which is independent of the appearance of the products which it designates. Average consumers are not in the habit of making assumptions about the origin of products on the basis of their shape or the shape of their packaging in the absence of any graphic or word element, and it could therefore prove more difficult to establish distinctive character in relation to such a three-dimensional mark than in relation to a word or figurative mark (see Freixenet v OHIM, cited in paragraph 12 above, paragraphs 45 and 46 and the case-law cited).

20 In those circumstances, only a mark which departs significantly from the norm or customs of the sector, and is thereby liable to fulfil its essential function of indicating origin, is not devoid of any distinctive character for the purposes of Article 7(1)(b) of Regulation No 207/2009 (see Freixenet v OHIM, cited in paragraph 12 above, paragraph 47 and the case-law cited).

21 With regard, in particular, to three-dimensional trade marks consisting of the packaging of goods, which are packaged in trade for reasons linked to the very nature of the product, the Court of Justice has held that they must enable average consumers of the goods in question, who are reasonably well informed and reasonably observant and circumspect, to distinguish the product concerned from those of other undertakings without conducting an analytical or comparative examination and without paying particular attention (Case C‑173/04 P Deutsche SiSi-Werke v OHIM [2006] ECR I‑551, paragraph 29).

22 In order to assess whether or not a trade mark has distinctive character, the overall impression which that mark makes must be considered. This does not mean, however, that one may not first examine each of the individual features of the get-up of that mark in turn. It may be useful, in the course of the overall assessment, to examine each of the components of which the trade mark concerned is composed (see Case C‑238/06 P Develey v OHIM [2007] ECR I‑9375, paragraph 82 and the case-law cited).

23 The first point to be noted is that, in the present case, the goods in question are desserts, ice creams, sorbets and yoghurts, and that the contested mark consists of the shape of two glass goblet-shaped transparent containers and the shape of a cardboard casing with openings at the top and on the sides and which follows the contours of the containers. The contested mark consists of the three-dimensional shape of the packaging of the goods in question.

24 The applicant alleges, in the first place, that the Board of Appeal identified the norm and customs of the sector concerned incorrectly. He submits that, for the purposes of its assessment of the distinctive character of the contested mark, the Board of Appeal ought to have taken into account the norm and customs of packaging in the sector of goods in Class 30. He claims that it restricted the norm and customs to be taken into consideration for the purposes of its analysis to those of the sector of packaging conveying ‘an image of quality and being handmade’.

25 That argument is based on an incorrect reading of the contested decision.

26 In the contested decision, the Board of Appeal observed that when, as in the present case, the contested mark consists of the three-dimensional shape of the packaging of the goods in question, the relevant norm or customs may be those which apply in the sector of the packaging of goods of the same type and which are intended for the same consumers as the goods in question.

27 The Board of Appeal then proceeded to examine separately the two elements of which the contested mark is composed, that is, the glass containers and the cardboard casing. In its assessment of the distinctive character of the glass containers, it stated that those types of container are used in the market for selling desserts, ice creams, sorbets and yoghurts and that they are used to convey to consumers the message that the goods in question are of high quality and handmade, which the applicant does not dispute. The Board of Appeal found that the shape of the containers in the contested mark did not depart substantially from that of the cups present on the market for the marketing of desserts, ice creams, sorbets and yoghurts, which was corroborated by the evidence provided by the intervener showing containers that differed only slightly from those of the contested mark. It inferred from this that that element of the contested mark was not distinctive for the goods in question.

28 The Board of Appeal then dismissed the examples provided by the applicant that referred to other types of container used on the market for the marketing of those goods, while observing that ‘their shape has not the same purpose of conveying to consumers an image of quality and being handmade’.

29 It is apparent from this that the Board of Appeal took into account the customs in the sector of the packaging of goods similar to the goods in question and intended for the same consumers as those of the goods in question, and found that packaging in the form of glass containers formed part of those customs, in particular in order to convey an image of quality. The fact that the Board of Appeal dismissed as irrelevant the evidence provided by the applicant concerning other shapes of container used to market ice creams does not contradict its finding that containers made of glass are also used on that market.

30 Contrary to what the applicant claims, it does not follow from the contested decision that the Board of Appeal restricted the norm and customs of the sector to be taken into consideration to the sector of quality and handmade goods alone.

31 The applicant submits, in the second place, that, as a consequence of identifying the norm and customs of the sector incorrectly, the Board of Appeal erred in its assessment of the distinctive character of the contested mark. He claims that the Board of Appeal took into account, as the point of comparison for the purpose of assessing the distinctive character of the contested mark, the concept of ‘packaging of goblets in a cardboard outer casing with cut-out openings’, instead of taking into account all types of packaging used in the sector of the goods in question. The Board of Appeal, he argues, therefore held incorrectly that the shapes of the cardboard casings with cut-out openings were commonly used in the sector of the goods in question. The applicant submits that the cardboard casing of the contested mark has different characteristics and is different in shape from those in the material provided as evidence by the intervener.

32 In the contested decision, in assessing the distinctive character of the second element of which the contested mark is composed, that is, the cardboard casing with openings at the top and on the sides, the Board of Appeal found that those characteristics were present in most of the cardboard casings provided as evidence by the intervener. It took the view that the shapes of cardboard casings with openings at the top and on the sides were common in the sector of the goods in question, in particular in order to show the product or any relevant information concerning the product. Taking into account the norm and customs of the sector of the goods in question (desserts, ice creams, sorbets and yoghurts), the Board of Appeal concluded that the shape of the cardboard casing of the contested mark was ornamental only, did not depart significantly from the customs of the sector and did not have distinctive character.

33 It should be observed that the Board of Appeal took as a basis the evidence provided by the intervener, which showed that, in the sector of the goods in question, packaging consisting of a cardboard casing with openings was commonly used, and it was entitled to infer from this that the contested mark did not depart significantly from the customs of the sector concerned.

34 The fact, as the applicant claims, that the shape of the cardboard casing of the contested mark departs in certain respects from the cardboard casings present on the market cannot call into question the Board of Appeal’s assessment in that regard. The various cardboard casings used in the sector of the goods in question, differing as to the location of their openings or as to their shapes, must be regarded as mere variants of the shapes of packaging used in that sector. The differences between the cardboard casings present on the market reflect, inter alia, practical considerations (such as adaptation to the size of the containers) or purely decorative ones. The Board of Appeal acted correctly in holding that the characteristics of the shape of the cardboard casing of the contested mark were not such as to result in its departing significantly from the customs of the sector of the goods in question.

35 The applicant submits, in the third place, that the Board of Appeal erred in the identification of the contested mark, by taking the contested mark to consist of ‘packaging of two goblets in a cardboard casing with cut-out openings’, which did not correspond to the contested mark as it was registered. He claims that the contested mark ought to have been considered as a whole, with its own characteristics. The Board of Appeal ought to have analysed the distinctive character of the combination of the particular shapes constituting the contested mark and not only that of the sum of its elements.

36 First of all, the applicant’s argument that the Board of Appeal identified the contested mark incorrectly must be rejected. The description of the contested mark set out in the contested decision, namely, ‘two glass goblet-shaped transparent containers in a cardboard outer casing open at the top and on the sides’ corresponds to the image of that mark as set out in the application for registration and as represented in paragraph 1 above. The fact that the applicant has his own description of the contested mark (namely, ‘two glass goblets placed side by side in a cardboard outer completely opened in correspondence of the top of the goblets and partially opened in correspondence of the front of the goblets, with peculiar shaped sides which follow and recall the shapes of the goblets, forming a particular cruet-shaped figure in the middle of these latter’), which does not appear in either the application for registration or in the certificate of registration, is not sufficient for it to be held that the Board of Appeal was in error.

37 Next, as regards the applicant’s argument that the Board of Appeal did not assess the contested mark as a whole, it must be pointed out that, in the contested decision, having found that the two elements constituting that mark did not depart substantially from those used in the sector of the goods in question and were devoid of any distinctive character, the Board of Appeal carried out an analysis of the overall impression produced by the shape of the packaging registered under the contested mark. It took the view that the contested mark’s own features were not sufficient to make it an unusual design on the market for desserts, ice creams, sorbets and yoghurts that could clearly be recognised as different from the forms available. It found that the examples provided by the intervener showed certain shapes of packaging that were very similar to the shape of the contested mark. The Board of Appeal took the view that the use of two containers held together by cardboard packaging was one of the most common ways of presenting the products to consumers. It concluded that, taken as a whole, the contested mark closely resembled the shapes that the goods in question were most likely to take and that, consequently, it had to be regarded as being devoid of any distinctive character.

38 It follows that the applicant cannot argue that the Board of Appeal did not carry out an overall assessment of the distinctive character of the contested mark, that it did not take account of its characteristics, and that it found merely that the sum of each of the elements of the contested mark lacked distinctive character.

39 The applicant also claims that the Board of Appeal was wrong to hold in the contested decision that the contested mark corresponded to a shape of packaging that is widely used on the market in order to market the goods in question, whereas the examples provided by him showed that the packaging that was the most commonly used in that sector was completely different from that of the contested mark.

40 In this connection, suffice it to point out that the fact that there are other types of packaging on the market for the goods in question is not inconsistent with the Board of Appeal’s finding that there are also shapes of packaging that are very similar to that of the contested mark and which are not unusual. In accordance with the case-law cited in paragraph 20 above, for a finding that a trade mark does not have distinctive character, it is sufficient that the mark does not depart significantly from the norm or customs of the sector and it is not necessary to show that that mark is the form of packaging that is the most common on the market.

41 The applicant claims, in the fourth place, that the Board of Appeal assessed the distinctive character of the contested mark too restrictively.

42 First, he claims that the case-law applied by the Board of Appeal, according to which, in order to have distinctive character for the purposes of Article 7(1)(b) of Regulation No 207/2009, a three-dimensional trade mark must depart significantly from the norm or customs of the sector, is not applicable where, as in the present case, the average consumer displays a high level of attention and where the contested mark does not consist of the shape of the goods but of their packaging.

43 That argument cannot succeed. Suffice it to recall that, as is apparent from paragraph 18 above, the Board of Appeal acted correctly in law in holding that the relevant public did not display a particularly high level of attention in relation to the goods in question. Furthermore, in the present case, the shape of the packaging must be regarded as equivalent to the shape of the goods in question.

44 Secondly, the applicant alleges that, in assessing the distinctive character of the contested mark, the Board of Appeal applied a stricter criterion than that required by the case-law. It required that the contested mark must ‘differ substantially’ from the basic shapes of the goods in question, whereas the case-law requires merely that it assess whether the contested mark ‘departs significantly’ from the norm and customs of the sector.

45 Suffice it to point out that, contrary to what the applicant claims, the requirement of a ‘substantial difference’ is not the criterion according to which the Board of Appeal assessed the distinctive character of the contested mark. In the contested decision, it is only after concluding that the contested mark did not have distinctive character that the Board of Appeal, citing the judgment in Case T‑15/05 De Waele v OHIM (Shape of a sausage) [2006] ECR II‑1511, used the expression ‘differ substantially’ in order to respond to the applicant’s argument concerning the novelty and originality of the shape of the contested mark.

46 The applicant also submits that, given that the Court acknowledged, in its judgment in Case T‑305/02 Nestlé Waters France v OHIM (Shape of a bottle) [2003] ECR II‑5207, that a three-dimensional mark in the shape of a bottle, registration of which was sought in respect of non-alcoholic beverages in Class 32, had a minimum degree of distinctive character for the purposes of Article 7(1)(b) of Regulation No 207/2009, the same approach ought to be applied in the present case, concerning a very similar sector, namely, that of goods in Class 30. In this connection, suffice it to recall that the distinctive character of a trade mark must be assessed by reference to the goods or services in respect of which registration has been sought and by reference to the relevant public’s perception of the mark, and that the Board of Appeal has to examine whether that mark departs significantly from the norm or customs of the sector of the goods in question. Therefore, the approach adopted by the Court in a judgment concerning a mark different from the contested mark, registration of which was sought in respect of goods different from those in the present case and in a different sector, is not relevant for the purposes of assessing the distinctive character of the contested mark in the present case.

47 It follows from the foregoing that the applicant has not shown that the Board of Appeal erred in taking the view that the contested mark was devoid of any distinctive character within the meaning of Article 7(1)(b) of Regulation No 207/2009.

48 The first plea in law must therefore be rejected.

Second plea in law, alleging infringement of Article 7(3) of Regulation No 207/2009

49 The applicant claims that the Board of Appeal misapplied Article 7(3) of Regulation No 207/2009 in taking the view that the evidence that he had provided was not sufficient to show that the contested mark had become distinctive through the use made of it.

50 Pursuant to Article 7(3) of Regulation No 207/2009, the absolute ground for refusal referred to in Article 7(1)(b) of that regulation does not prevent registration of a mark if that mark has become distinctive in relation to the goods for which registration is requested in consequence of the use which has been made of it.

51 Article 52(2) of Regulation No 207/2009 provides, inter alia, that, where the Community trade mark has been registered contrary to the provisions of Article 7(1)(b) of that regulation, it may nevertheless not be declared invalid if, in consequence of the use which has been made of it, it has after registration acquired distinctive character in relation to the goods or services for which it is registered.

52 It is apparent from the case-law that the acquisition of distinctive character through use of a mark requires that at least a significant proportion of the relevant public identifies the goods or services concerned as originating from a particular undertaking because of the mark (see Case T‑262/04 BIC v OHIM (Shape of a lighter) [2005] ECR II‑5959, paragraph 61 and the case-law cited).

53 In the present case, the Board of Appeal observed that, as the contested mark was a three-dimensional mark, the relevant territory was that of the European Union. It took the view that the evidence provided by the applicant was not sufficient to demonstrate that the contested mark had acquired distinctive character for the purposes of Article 7(3) and Article 52(2) of Regulation No 207/2009. It found, first, that that evidence, taken as a whole, related to only eight Member States of the European Union and that it therefore did not demonstrate that distinctive character had been acquired in a substantial part of the European Union. The Board of Appeal found, secondly, that the applicant had not proved that the contested mark had been perceived as a designation of the origin of the goods, on account of the fact that the shape of the packaging had always been used in conjunction with the sign LA GELATERIA DI PIAZZA NAVONA printed on that packaging.

54 In the first place, the applicant merely asserts that the use of the contested mark in conjunction with the sign LA GELATERIA DI PIAZZA NAVONA printed on the packaging demonstrates that the relevant consumer perceives, besides the graphic representation, the three-dimensional shape as an indication of the origin of the goods in question. Suffice it to state that that mere assertion cannot call into question the Board of Appeal’s conclusion that that evidence was not sufficient to show use of the contested mark as a trade mark and that it had, therefore, to be rejected.

55 In any event, it is necessary to point out that, admittedly, according to the case-law, a three-dimensional mark may acquire distinctive character through use even if it is used in conjunction with a word mark or a figurative mark. Such is the case where the mark consists of the shape of the product or its packaging and where the product and its packaging systematically bear a word mark under which they are marketed. Such distinctive character may be acquired, inter alia, after the normal process of familiarising the public concerned has taken place (see judgment of 29 January 2013 in Case T‑25/11 Germans Boada v OHIM (Manual tile-cutting machine), not published in the ECR, paragraph 83 and the case-law cited).

56 However, the identification by the relevant class of persons of the product as originating from a particular undertaking must be made as a result of the use of the mark as a trade mark. The expression ‘use of the mark as a trade mark’ must be understood as referring to use of the mark for the purposes of the identification by the relevant class of persons of the product or service as originating from a particular undertaking. Therefore, not every use of the mark amounts necessarily to use as a trade mark (Manual tile-cutting machine, cited in paragraph 55 above, paragraph 85).

57 In the circumstances of the present case, it would only have been if the applicant had specifically substantiated the assertion that the shape of the packaging of the goods in question was particularly retained by the relevant consumers in their memory as an indication of its commercial origin, that it might, perhaps, have been possible to see from the evidence presented initial support for the proposition, that is, that the particular appearance of the three-dimensional shape of the packaging of the goods in question constituting the contested mark made it possible to differentiate it from those of other manufacturers. Suffice it to observe that the applicant has not put forward any argument to that effect.

58 In the second place, with regard to the applicant’s argument that the Board of Appeal did not take into account the fact that the evidence which he had provided covered a substantial portion of consumers in the European Union, that argument must be rejected as ineffective in so far as the applicant has not shown that the Board of Appeal erred in holding that that evidence did not demonstrate that the contested mark has been used as a trade mark.

59 It follows that the second plea in law must be rejected and, therefore, that the action must be dismissed in its entirety.

Costs

60 Under Article 87(2) of the Rules of Procedure of the General Court, the unsuccessful party is to be ordered to pay the costs if they have been applied for in the successful party’s pleadings. Since the applicant has been unsuccessful, he must be ordered to pay the costs, in accordance with the forms of order sought by OHIM and the intervener.

On those grounds,

THE GENERAL COURT (Seventh Chamber)

hereby:

1. Dismisses the action;

2. Orders Mr Giorgio Giorgis to pay the costs.

Van der Woude | Wiszniewska-Białecka | Ulloa Rubio |

Delivered in open court in Luxembourg on 25 September 2014.

[Signatures]