JUDGMENT OF THE GENERAL COURT (Seventh Chamber)

27 June 2013 (*)

(Community design – Invalidity proceedings – Registered Community design representing an instrument for writing – Earlier national figurative and three-dimensional trade marks – Ground for invalidity – Use in the Community design of an earlier sign the holder of which has the right to prohibit such use – Article 25(1)(e) of Regulation (EC) No 6/2002 – Decision taken following the annulment by the General Court of an earlier decision)

In Case T‑608/11,

Beifa Group Co. Ltd, established in Ningbo (China), represented by R. Davis, Barrister, N. Cordell, Solicitor, and B. Longstaff, Barrister,

applicant,

v

Office for Harmonisation in the Internal Market (Trade Marks and Designs) (OHIM), represented by A. Folliard-Monguiral, acting as Agent,

defendant,

the other party to the proceedings before the Board of Appeal of OHIM, intervener before the General Court, being

Schwan-Stabilo Schwanhäußer GmbH & Co. KG, established in Heroldsberg (Germany), represented by H. Gauß and U. Blumenröder, lawyers,

ACTION brought against the decision of the Third Board of Appeal of OHIM of 9 August 2011 (Case R 1838/2010‑3) relating to invalidity proceedings between Schwan-Stabilo Schwanhäußer GmbH & Co. KG and Ningbo Beifa Group Co., Ltd,

THE GENERAL COURT (Seventh Chamber),

composed of A. Dittrich (President), I. Wiszniewska-Białecka and M. Prek (Rapporteur), Judges,

Registrar: T. Weiler, Administrator,

having regard to the application lodged at the Registry of the General Court on 30 November 2011,

having regard to the response of OHIM lodged at the Registry of the Court on 30 March 2012,

having regard to the response of the intervener lodged at the Registry of the Court on 21 March 2012,

further to the hearing on 21 February 2013, in which the applicant did not take part,

gives the following

Judgment

Background to the dispute

1 On 27 May 2005, the applicant, Beifa Group Co. Ltd, formerly Ningbo Beifa Group Co., Ltd, filed an application for registration of a Community design with the Office for Harmonisation in the Internal Market (Trade Marks and Designs) (OHIM), pursuant to Council Regulation (EC) No 6/2002 of 12 December 2001 on Community designs (OJ 2002 L 3, p. 1).

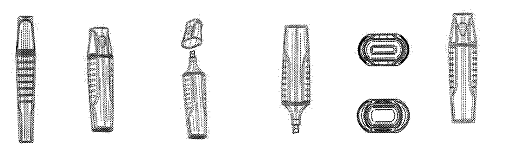

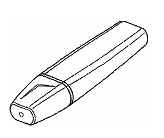

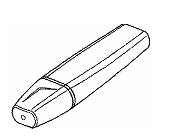

2 That application covered the design below (‘the design in dispute’):

3 In its application for registration, the applicant claimed a right of priority for the design in dispute, in accordance with Articles 41 to 43 of Regulation No 6/2002, on the basis of an earlier application for registration of the same design which had been lodged with the competent Chinese authority on 5 February 2005.

4 In accordance with Article 36(2) of Regulation No 6/2002, the application indicated ‘instruments for writing’ as goods in which the design in dispute was intended to be incorporated or to which it was intended to be applied.

5 The design in dispute was registered as Community design No 352315 0007 and published in Community Designs Bulletin No 68/2005 of 26 July 2005.

6 On 23 March 2006, the intervener, Schwan-Stabilo Schwanhäußer GmbH & Co. KG, acting pursuant to Article 52 of Regulation No 6/2002, submitted to OHIM an application for a declaration that the design in dispute was invalid, in which it claimed that the grounds for invalidity listed in Article 25(1)(b) and (e) of Regulation No 6/2002 precluded the design in dispute from being maintained.

7 The application for a declaration of invalidity was based on, inter alia, the following marks of the intervener:

– the figurative mark, registered in Germany on 14 December 2000 under No 300454708 for, inter alia, ‘instruments for writing’ in Class 16 of the Nice Agreement of 15 June 1957 concerning the International Classification of Goods and Services for the Purposes of the Registration of Marks, as revised and amended, (‘the earlier figurative mark’), reproduced below:

– the three-dimensional mark, registered in Germany on 21 August 1995 under No 2911311 for, inter alia, ‘instruments for writing’ in Class 16 of the Nice Agreement (‘the earlier three-dimensional mark’), reproduced below:

8 By decision of 24 August 2006, the Invalidity Division of OHIM upheld the intervener’s application for a declaration of invalidity and, accordingly, declared the design in dispute to be invalid on the ground specified in Article 25(1)(e) of Regulation No 6/2002.

9 In substance, the Invalidity Division found that the earlier mark was used in the design in dispute, in that a sign with all the characteristic features of the three-dimensional shape of the earlier figurative mark, and in consequence similar to that mark, was incorporated in the design in dispute. Since the goods covered by the design in dispute were identical to those covered by the earlier figurative mark, there was – in the view of the Invalidity Division – a likelihood of confusion on the part of the relevant public, which gave the intervener the right, under Paragraph 14(2)(2) of the Gesetz über den Schutz von Marken und sonstigen Kennzeichen (German Law on the protection of trade marks and other distinctive signs) of 25 October 1994 (BGBl. I, 1994, p. 3082; ‘the Markengesetz’)), to prohibit the use of the sign used in the design in dispute.

10 On 19 October 2006, the applicant appealed under Articles 55 to 60 of Regulation No 6/2002 against the decision of the Invalidity Division.

11 By decision of 31 January 2008 (‘the 2008 decision’), the Third Board of Appeal of OHIM dismissed the applicant’s appeal.

12 By application lodged at the Registry of the General Court on 21 April 2008, the applicant brought an action against the 2008 decision, which was registered as Case T‑148/08.

13 By its judgment of 12 May 2010 in Case T‑148/08 Beifa Group v OHIM – Schwan-Stabilo Schwanhäußer (Instrument for writing) [2010] ECR II‑1681 (‘the Instrument for writing judgment’), the General Court annulled the 2008 decision.

14 In paragraph 59 of the Instrument for writing judgment, it was held that ‘the Board of Appeal did not err in law by interpreting Article 25(1)(e) of Regulation No 6/2002 as meaning that the proprietor of a distinctive sign may rely on that provision for the purposes of applying for a declaration of invalidity in respect of a subsequent Community design, where use is made in that design of a sign similar to its own.’

15 In paragraph 77 of the Instrument for writing judgment, it was pointed out that ‘[e]ven assuming that the pleadings setting out the grounds on which [the applicant] relied before the Board of Appeal could be construed as containing a request for proof of genuine use of the earlier mark, a request of that kind, made for the first time before the Board of Appeal, is inadmissible and cannot be taken into consideration and examined by the Board of Appeal.’

16 In paragraphs 113, 114 and 116 of the Instrument for writing judgment, the Court stated that ‘the only mark taken into consideration by the various adjudicating bodies within OHIM, when considering the application for a declaration of invalidity, was the earlier [figurative] mark’. However, the Court noted that ‘the Cancellation Division compared [the contested] design with a three-dimensional mark which was not identified in its decision’ and that ‘[t]hat error … was in no way rectified by the Board of Appeal’.

17 Consequently, in paragraph 117 of the Instrument for writing judgment, the Court held that ‘since, in the contested decision, the Board of Appeal based its conclusion as to the likelihood of confusion between the design in dispute and the earlier [figurative] mark on the comparison of that design with a sign other than the earlier [figurative] mark, [namely the earlier three-dimensional mark], it erred in law and the contested decision must be annulled.’

18 In that regard, in paragraphs 121, 122 and 124 of the Instrument for writing judgment, the Court stated that ‘[a] three-dimensional mark, however, is not necessarily perceived by the relevant public in the same way as a figurative mark’ and that, even if ‘[t]he possibility cannot be ruled out, of course, that where two three-dimensional objects are similar, a comparison of one of those objects with an image of the other might also lead to a finding that they are similar … , it [was not for] the Court itself to be the first to undertake a comparison of the design in dispute with the earlier [figurative] mark, since no such comparison was made either by the Cancellation Division or by the Board of Appeal’.

19 The Court also observed, in paragraph 131 of the Instrument for writing judgment, that, ‘[as] regards the arguments put forward by Stabilo – the first relating to the fact that Stabilo is the proprietor of an unregistered three-dimensional mark bearing a similarity to the design in dispute; the second relating to [Paragraph] 14(2)(3) of the Markengesetz; the third relating to the additional protection arising from the provisions of German law against unfair competition; and the fourth relating to the ground for invalidity specified in Article 25(1)(b) of Regulation No 6/2002 – [it was sufficient] to point out that … the Board of Appeal did not find it necessary to consider the merits of those issues, which … the Court cannot itself be the first to examine.’

20 Finally, the Court found in paragraph 133 of the Instrument for writing judgment that ‘[the applicant’s] interests [were] sufficiently safeguarded by annulment of the contested decision, without there being any need to refer the case back to the Cancellation Division’ and rejected the applicant’s second head of claim.

21 By decision of 28 September 2010, the Presidium of the Boards of Appeal of OHIM reallocated the case to the Third Board of Appeal. The case was assigned the reference number R 1838/2010-3.

22 By decision of 9 August 2011 (‘the contested decision’), notified to the applicant on 20 September 2011, the Third Board of Appeal again dismissed the applicant’s appeal and ordered it to pay the costs.

23 In the contested decision, the Board of Appeal limited its examination of Article 25(1)(e) of Regulation No 6/2002 to the earlier three-dimensional mark (paragraph 20 of the contested decision). In essence, first, the Board of Appeal held that, in accordance with the Instrument for writing judgment, the intervener was not required to submit proof of genuine use of that mark because the applicant had failed to file the corresponding request before the Invalidity Division (paragraph 24 of the contested decision).

24 The Board of Appeal considered that, despite the existence of certain differences between the contested design and the earlier three-dimensional mark, the characteristic features of that mark could be discerned in the contested design. Accordingly, it found that use had been made of the earlier three-dimensional mark in the contested design, within the terms of Article 25(1)(e) of Regulation No 6/2002 (paragraphs 28 to 30 of the contested decision).

25 The Board of Appeal held that, taking into account the similarity of the contested design and the earlier three-dimensional mark and the identity of the products in which that design was intended to be incorporated and the goods covered by that mark, there was a likelihood of confusion within the meaning of Paragraph 14(2)(2) of the Markengesetz, without it being necessary to examine the enhanced distinctiveness of the earlier three-dimensional mark. Consequently, it declared the contested design to be invalid (paragraphs 48, 49 and 51 of the contested decision).

26 Secondly, the Board of Appeal declared the contested design to be invalid also on the ground of lack of individual character, in accordance with Article 25(1)(b) of Regulation No 6/2002 (paragraph 65 of the contested decision).

Forms of order sought

27 The applicant claims that the Court should:

– annul the contested decision;

– order OHIM to pay the costs.

28 OHIM and the intervener contend that the Court should:

– dismiss the action;

– order the applicant to pay the costs.

Law

29 The applicant puts forward seven pleas in law in support of its action, alleging, respectively, infringement of Article 61(6) of Regulation No 6/2002 (first plea in law), infringement of Article 62 of that regulation (second and third pleas in law), misinterpretation of Article 25(1)(e) of the same regulation (fourth plea in law), an error of law vitiating the rejection of the request for proof of genuine use of the earlier mark (fifth plea in law), incorrect application of Article 25(1)(e) of Regulation No 6/2002 (sixth plea in law) and incorrect application of Article 25(1)(b) of the same regulation (seventh plea in law).

The first plea in law, alleging infringement of Article 61(6) of Regulation No 6/2002

30 The applicant claims that the re-examination ab initio by the Third Board of Appeal, which led to the contested decision, was not a ‘necessary’ measure for compliance with the Instrument for writing judgment, within the meaning of Article 61(6) of Regulation No 6/2002. According to the applicant, it would have sufficed to annul the decision of the Invalidity Division which found the contested design to be invalid. In the alternative, if measures were necessary, its examination should have been limited to the arguments in relation to the earlier figurative mark.

31 The present plea in law cannot be upheld.

32 According to settled case-law, a judgment annulling a measure takes effect ex tunc and thus has the effect of retroactively eliminating the annulled measure from the legal system (see, by analogy, Case T‑402/07 Kaul v OHIM – Bayer (ARCOL) [2009] ECR II‑737, paragraph 21 and the case-law cited).

33 According to the same case-law, in order to comply with a judgment annulling a measure and to implement it fully, the institution that is the author of the measure is required to have regard not only to the operative part of the judgment but also to the grounds constituting its essential basis, in so far as they are necessary to determine the exact meaning of what is stated in the operative part. It is those grounds which, on the one hand, identify the precise provision held to be illegal and, on the other, indicate the specific reasons which underlie the finding of illegality contained in the operative part and which the institution concerned must take into account when replacing the annulled measure (see, by analogy, ARCOL, paragraph 22 and the case-law cited).

34 In the present case, following annulment of the 2008 decision, the appeal brought by the applicant before the Board of Appeal again became pending. In order to comply with its obligation under Article 61(6) of Regulation No 6/2002 to take the measures necessary to comply with the Instrument for writing judgment, OHIM had to ensure that the appeal led to a new decision of a Board of Appeal. That was indeed what occurred, as the case was reallocated to the Board of Appeal, which adopted the contested decision (see, to that effect and by analogy, ARCOL, paragraph 23).

35 In the Instrument for writing judgment, the Court held that, in the 2008 decision, the Board of Appeal based its conclusion as to the likelihood of confusion between the contested design and the earlier figurative mark on the comparison of that design with a sign other than the earlier figurative mark (namely, the earlier three-dimensional mark) and that it therefore erred in law (paragraph 117). Consequently, the Court annulled the 2008 decision.

36 Therefore, the Third Board of Appeal was required to carry out a fresh examination of the applicant’s appeal against the decision of the Invalidity Division and, in particular, of the grounds for invalidity referred to in Article 25(1) of Regulation No 6/2002 and relied on by the intervener. Following that examination, it could reach its own conclusion, independent of the position adopted in the 2008 decision.

37 It follows from Article 60(1) of Regulation No 6/2002 that, through the effect of the appeal before it, the Board of Appeal is called upon to carry out a new, full examination of the merits of the application for invalidity, in terms of both law and fact (Case C‑29/05 P OHIM v Kaul [2007] ECR I‑2213, paragraph 57). This means that the Board of Appeal may base its decision on any of the grounds for invalidity referred to in Article 25(1) of Regulation No 6/2002 and on any of the earlier trade marks relied on by the applicant for invalidity, without being bound by the content of the decision of the Invalidity Division and without having to provide specific reasons in that regard. In the present case, it is not disputed that the earlier three-dimensional mark and the ground for invalidity referred to in Article 25(1)(b) of that regulation were relied on by the intervener during the procedure before the Invalidity Division. The Board of Appeal was, therefore, entitled to base its decision on the comparison between the contested design and that trade mark and on the examination of the novelty and individual character of that design.

38 In that regard, it should be pointed out that, contrary to what is claimed by the applicant, the Court did not hold, in paragraph 133 of the Instrument for writing judgment, that it was not necessary to re-examine the other grounds for invalidity relied on by the intervener and not examined by the Board of Appeal in the 2008 decision. In that paragraph, the Court, on the contrary, rejected the applicant’s second head of claim, seeking that the case be remitted to the Invalidity Division in order for those other grounds of invalidity to be examined. In that context, it held, in accordance with the principles referred to above, that the interests of the applicant were sufficiently safeguarded by annulment of the 2008 decision, without there being need to refer the case back to the Invalidity Division.

39 The Board of Appeal was also not bound, on that point, by the operative part and reasoning of the Instrument for writing judgment, since, in that judgment, the Court did not in any way express a view on those other grounds for invalidity and found solely that these were questions which the Board of Appeal had held not to be necessary to examine in detail and which the Court could not itself examine for the first time.

40 It follows from the foregoing that the Third Board of Appeal did not infringe Article 61(6) of Regulation No 6/2002.

The second plea in law, alleging infringement of the right to be heard (Article 62 of Regulation No 6/2002)

41 According to the applicant, the principle set out in Article 62 of Regulation No 6/2002 was infringed, as the contested decision was based on ‘new’ matters with respect to which the applicant had not been able to express a view, namely the earlier three-dimensional mark and the ground for invalidity referred to in Article 25(1)(b) of Regulation No 6/2002 and alleging a lack of novelty and individual character of the contested design, as those questions had not been ruled upon previously at all.

42 According to Article 62 of Regulation No 6/2002, decisions of OHIM are to be based only on reasons or evidence on which the parties concerned have had an opportunity to present their comments. The general principle of protection of the right to defend oneself is enshrined in the law of Community designs by that provision. According to that general principle of European Union law, a person whose interests are significantly affected by a decision addressed to that person and taken by a public authority must be given the opportunity to make his point of view known. The right to be heard extends to all the matters of fact or of law which form the basis of the decision, but not to the final position which the authority intends to adopt (see, by analogy, ARCOL, paragraph 55, and Case T‑262/09 Safariland v OHIM – DEF-TEC Defense Technology (FIRST DEFENSE AEROSOL PEPPER PROJECTOR) [2011] ECR II‑1629, paragraphs 79 and 80 and the case-law cited).

43 In the present case, following the annulment of the 2008 decision by the Court, the case was referred back to the Third Board of Appeal, which was called upon, following re-examination of the case, to rule on the appeal brought by the applicant against the decision of the Invalidity Division.

44 In the first place, by the contested decision, the Third Board of Appeal dismissed the applicant’s action on the grounds, firstly, that there was a likelihood of confusion between the contested design and the earlier three-dimensional mark and, secondly, that the contested design lacked individual character.

45 It follows from the case-file that, in the course of the proceedings which led to the adoption of the 2008 decision, the applicant had the opportunity to submit its observations relating to all aspects of the application for a declaration of invalidity, including the comparison between the contested design and the earlier three-dimensional mark and the novelty and individual character of that design. A summary of those observations submitted in response to the application for a declaration of invalidity is set out in paragraph 6 of the contested decision. The applicant also submitted observations on the earlier three-dimensional mark in its action before the Board of Appeal.

46 In that regard, it has been held that it follows from the continuity of functions between the departments of OHIM that, within the scope of Article 63(1) in fine of Regulation No 6/2002, the Board of Appeal is required to base its decision on all the matters of fact and of law which the party concerned introduced either in the proceedings before the department which heard the application at first instance or, subject only to Article 63(2), in the appeal. The extent of the examination which the Board of Appeal is required to conduct in respect of the decision which forms the subject-matter of the action is not, in principle, determined by the grounds relied on by the party which has brought the appeal (see, by analogy, Case T‑308/01 Henkel v OHIM – LHS (UK) (KLEENCARE) [2003] ECR II‑3253, paragraphs 29 and 32).

47 To the extent to which it is common ground that the intervener put forward the two grounds for invalidity during the proceedings before the Invalidity Division, it must be held that these were included in the case-file put before the Third Board of Appeal. The latter, therefore, did not decide on the basis of any new matters.

48 The applicant claims that the Board of Appeal requested the parties to express their views on two specific points of law, although the contested decision is based on other points, including one with respect to which only the intervener expressed a view.

49 In that regard, it is apparent from the case-file that, on 9 December 2010, the Chairperson of the Third Board of Appeal requested the parties to submit their observations concerning the consequences of the Instrument for writing judgment for the re-examination of the case, including the relevance and existence of a likelihood of confusion for the purposes of German law concerning the earlier figurative mark. They were also requested to submit their observations on Paragraph 34(1) of the Markengesetz.

50 It must therefore be held that, contrary to what is claimed by the applicant, the latter was not requested to make observations exclusively, but ‘inter alia’, about the earlier figurative mark. Moreover, the Board of Appeal pointed out in that communication that, in accordance with Article 10 of Commission Regulation (EC) No 216/96 of 5 February 1996 laying down the rules of procedure of the Boards of Appeal of OHIM (OJ 1996 L 28, p. 11), as amended by Commission Regulation (EC) No 2082/2004 of 6 December 2004 (OJ 2004 L 360, p. 8), that communication could not be interpreted as capable of binding the Board of Appeal. In contrast to what is claimed by the applicant, that communication could not have given the parties any legitimate expectation concerning the ‘[necessary] measures’ which should have been adopted by the Board of Appeal.

51 Furthermore, it should be borne in mind that the second sentence of Article 62 of Regulation No 6/2002 in no way requires that, following resumption of the proceedings before OHIM after a decision of the Board of Appeal has been annulled by the Court, the parties again be invited to submit observations on points of law and fact on which they have already had ample opportunity to express their views in the course of the written procedure previously conducted, given that the file, as then constituted, has been taken over by the Board of Appeal (see, by analogy, FIRST DEFENSE AEROSOL PEPPER PROJECTOR, paragraph 84 and the case-law cited). Contrary to what the applicant claims, that provision also does not require that the parties be informed of the factual or legal elements on the basis of which the new decision will be taken.

52 Finally, it does not in any way follow from the contested decision that the Third Board of Appeal, when it adopted that decision, relied on matters of law or of fact which differed from those available to the Board of Appeal when it adopted the 2008 decision and on which the applicant had been able to submit observations.

53 In the second place, the applicant also cannot claim that the Board of Appeal infringed its right to be heard by not allowing it to submit observations on the referral of the case to the Third Board of Appeal following the Instrument for writing judgment, or on the decision not to remit it to the Invalidity Division.

54 The referral was carried out pursuant to Article 1d of Regulation No 216/96. That article provides, in relation to the referral of a case following a ruling of the Courts of the European Union, that if the measures necessary to comply with a judgment of those Courts annulling all or part of a decision of a Board of Appeal or of the Grand Board of OHIM include re-examination by the Boards of Appeal of the case which was the subject of that decision, the Presidium is to decide whether the case is to be referred to the Board which adopted that decision, or to another Board, or to the Grand Board of OHIM.

55 That provision does not, however, provide for the possibility of a referral back to the lower adjudicating body, or for any right of the parties to be heard in that regard. It is a purely procedural decision and does not require the examination of any matter of fact or law in order to be taken. Furthermore, the applicant does not adduce any evidence capable of showing that such a referral would significantly affect its interests.

56 In particular, concerning the fact that the case was not remitted to the Invalidity Division, and as was pointed out in paragraph 37 above, it follows from Article 60(1) of Regulation No 6/2002 that, through the effect of the appeal before it, the Board of Appeal is called upon to carry out a new, full examination of the merits of the application for invalidity, in terms of both law and fact, and to rule on that action. In so doing, it may either exercise any power within the competence of the body which took the contested decision, that is to say, give a decision itself on the application for a declaration of invalidity, or refer the case back to that body in order to be pursued further. Contrary to what is claimed by the applicant, neither Article 60(1) nor the second sentence of Article 62 of Regulation No 6/2002 requires that, following the resumption of the proceedings before OHIM, after annulment of a decision of the Board of Appeal by the General Court, the parties be invited to comment on that matter.

57 The applicant also claims to have been adversely affected, since it was deprived of the legitimate opportunity to challenge the use of the earlier trade marks because of the failure to remit the case back to the Invalidity Division.

58 In that regard, suffice it to point out that, as is apparent from the case-law referred to above and as the Court noted in paragraphs 67 and 68 of its Instrument for writing judgment, a request for proof of genuine use of the earlier sign by the proprietor of a Community design in respect of which an application for a declaration of invalidity has been brought on the basis of the earlier sign must be submitted to OHIM expressly and in due time, that is to say, within the period of time granted by the Invalidity Division to the proprietor of the Community design at issue for submitting its observations in response to the application for a declaration that the design is invalid and cannot be made for the first time before the Board of Appeal or subsequently, in the context of the resumption of the proceedings before OHIM, after a decision of the Board of Appeal has been annulled by the Court.

59 In such a context, it is unacceptable that a department of OHIM could be put in the position of having to rule on a dispute which is different from the dispute initially brought before the Invalidity Division, that is to say, a dispute the scope of which has been extended through the introduction of the preliminary issue of genuine use of the earlier sign, relied on in support of the application for a declaration of invalidity (see, to that effect, the Instrument for writing judgment, paragraph 71).

60 In paragraphs 76 and 77 of the Instrument for writing judgment, the Court already found that the applicant had referred to the issue of proof of genuine use of the earlier figurative mark for the first time in the pleadings setting out the grounds for its appeal before the Board of Appeal. The Court accordingly held that, even assuming that those pleadings could be construed as containing a request for proof of genuine use of the earlier figurative mark, a request of that kind, made for the first time before the Board of Appeal, was inadmissible and could not be taken into consideration and examined by the Board of Appeal.

61 Moreover, the applicant confirms that it made a request for proof of use of the intervener’s earlier marks for the first time before the Board of Appeal.

62 The applicant proceeds on the mistaken premise that a remittal of the case to the Invalidity Division would give it the possibility to restart the proceedings from the beginning, to re-establish its case-file and thus to rectify the omissions confirmed in the course of the first proceedings. However, such a finding would amount to stating that, in the case where the Court annuls a decision of the Board of Appeal, the parties are given the opportunity to bring new proceedings in the context of which OHIM would be put in a position of having to rule on a dispute the scope of which would be different from that submitted on the first occasion (see the Instrument for writing judgment, paragraph 71; see also paragraph 59 above). The applicant’s argument must for that reason be rejected.

63 In the light of the foregoing, the second plea in law must be rejected.

The third plea in law, alleging infringement of Article 62 of Regulation No 6/2002

64 In paragraphs 30, 43 and 63 of the contested decision, the Board of Appeal took the view that the differences referred to between the Community design and the earlier three-dimensional mark consisted of small surface interruptions which are common for writing instruments as a means of enhancing their grip and that, consequently, the public will pay less attention to the particular design of the highlighters’ surface and more attention to their overall shape.

65 The applicant claims that that finding by the Board of Appeal was not supported by any evidence and that, therefore, it did not have the opportunity to express a view or adduce evidence on that point.

66 That argument cannot establish any infringement of Article 62 of Regulation No 6/2002.

67 It should be borne in mind that the obligation to state reasons has two purposes: to allow interested parties to know the justification for the measure taken so as to enable them to protect their rights and to enable the Courts of the European Union to exercise their power to review the legality of the decision (judgment in Joined Cases T‑83/11 and T‑84/11 Antrax It v OHIM – THC (radiators for heating) [2012] ECR II‑0000, paragraph 98). However, the Boards of Appeal cannot be required to provide an account that follows exhaustively and one by one all the lines of reasoning articulated by the parties before them. The reasoning may, therefore, be implicit, on condition that it enables the persons concerned to know the reasons for the Board of Appeal’s decision and provides the competent Court with sufficient material for it to exercise its power of review (Case T‑304/06 Reber v OHIM – Chocoladefabriken Lindt & Sprüngli (Mozart) [2008] ECR II‑1927, paragraph 55, and judgment of 11 October 2011 in Case T‑87/10 Chestnut Medical Technologies v OHIM (PIPELINE), not published in the ECR, paragraph 41).

68 Moreover, it is apparent from settled case-law that the obligation to state reasons is an essential procedural requirement, as distinct from the question whether the reasons given are correct, which goes to the substantive legality of the contested measure (see Joined Cases T‑239/04 and T‑323/04 Italy v Commission [2007] ECR II‑3265, paragraph 117 and the case-law cited). The fact that a statement of reasons may be incorrect does not mean that it is non-existent (see judgment of 12 September 2012 in Case T‑295/11 Duscholux Ibérica v OHIM – Duschprodukter i Skandinavien (duschy), not published in the ECR, paragraph 41 and the case-law cited).

69 The Board of Appeal’s findings which are contested by the applicant go to the substantive legality of the contested decision and do not relate to the obligation to state reasons.

70 Furthermore, in the context of the present plea in law, the applicant does not claim that the Board of Appeal based the contested decision on evidence in respect of which the applicant was not able to express a view, but that the contested findings were not supported by any evidence.

71 However, that argument cannot support a finding that there was an error on the part of the Board of Appeal.

72 In that regard, it should be recalled that, according to Article 63 of Regulation No 6/2002, ‘in proceedings relating to a declaration of invalidity, [OHIM] shall be restricted in [its] examination to the facts, evidence and arguments provided by the parties and the relief sought’.

73 In the present case, it is apparent from the case-file that the differences between the contested design and the earlier trade marks were mentioned and were the subject of respective assessments by the two parties.

74 In the passages of the contested decision referred to in paragraph 64 above, the Board of Appeal did not introduce new facts, whether well-known or not, but undertook an assessment of the similarity between the contested design and the earlier three-dimensional mark and an assessment of the novelty and individual character of that design on the basis of the facts presented to it. Consequently, the Board of Appeal, in undertaking that analysis, did not go beyond the bounds of the dispute between the parties.

75 Furthermore, contrary to what the applicant claims, the Board of Appeal did not hold that only the basic shape of the writing instrument mattered and that the details could be ignored. On the contrary, it is precisely because of those differences that the Board of Appeal concluded that the contested design and the earlier three-dimensional mark were similar and not identical. Likewise, during the examination of the novelty and individual character of the contested design, the Board of Appeal held that the differences highlighted by the applicant could not be described as immaterial, but that they were not sufficient to affect the overall impression that the designs concerned had on the informed user (paragraph 62 of the contested decision).

76 It is also necessary to reject the applicant’s argument that those findings of the Board of Appeal are contrary to the observations of the intervener, which considered that the consumer will view the frets and garnishments on the Community design as garnishments. First, the applicant does not show how such a finding is contrary to Article 62 of Regulation No 6/2002. Secondly, that argument must be rejected even on the assumption that the applicant intends thereby to invoke infringement of Article 63 of that regulation. The intervener clearly based its application for a declaration of invalidity on its earlier trade marks. On that basis, the Board of Appeal was required to compare those trade marks with the contested design. During that procedure, however, it was not bound, under that provision, by the intervener’s appraisal of the contested design.

77 Finally, the applicant’s claim that ‘the finding and the approach’ taken by the Board of Appeal are wholly inconsistent with OHIM’s general practice as to the registration of designs in the field of writing instruments cannot be upheld. The procedure for the registration of Community designs established by Regulation No 6/2002 consists of an essentially formal, expeditious check, which, as indicated in recital 18 of the preamble to that regulation, does not require any substantive examination as to compliance with the requirements for protection prior to registration (Case C‑488/10 Celaya Emparanza y Galdos Internacional [2012] ECR I‑0000, paragraphs 41 and 43). Furthermore, the applicant refers solely to registrations of different designs of the intervener with respect to which the issue of a likelihood of confusion is not relevant.

78 The third plea in law is consequently unfounded.

The fourth plea in law, alleging misinterpretation of Article 25(1)(e) of Regulation No 6/2002

79 In the context of the present plea in law, the applicant puts forward the same arguments as in the context of the first plea in law in the case which gave rise to the Instrument for writing judgment (paragraphs 46 to 59).

80 The applicant thus claims that it is apparent from the very wording of Article 25(1)(e) of Regulation No 6/2002 that, contrary to the findings of the Board of Appeal, that provision cannot be relied upon by the proprietor of a distinctive sign where the sign used in a subsequent design is not the sign in question, but only a similar sign. That interpretation of the provision in question is, it submits, confirmed not only by the fact that a Community design relates solely to the appearance of a product and is not specific to any particular goods, but also by OHIM’s earlier decision-making practice.

81 Those arguments cannot be accepted.

82 As the Court held, in particular, in paragraphs 52 and 59 of the Instrument for writing judgment, a literal interpretation of Article 25(1)(e) of Regulation No 6/2002 does not necessarily preclude the application of that provision in the case where use is made, in a subsequent Community design, not of a sign which is identical to that relied upon in support of the application for a declaration of invalidity, but of a sign which is similar. Consequently, the Board of Appeal did not err in law in interpreting Article 25(1)(e) of Regulation No 6/2002 as meaning that the proprietor of a distinctive sign may rely on that provision for the purposes of applying for a declaration of invalidity in respect of a subsequent Community design in the case where use is made in that design of a sign similar to its own. The Board of Appeal set out that finding in the contested decision (paragraph 22).

83 More particularly, it is necessary to reject the applicant’s criticism that, contrary to the finding in paragraph 53 of the Instrument for writing judgment, the way in which Article 25(1)(e) of Regulation No 6/2002 is construed in the 2008 decision and confirmed by the Court, is not the only way of ensuring effective protection of the rights of the proprietor of an earlier mark, since both the current legislation on Community trade marks and Article 25(1)(b) of Regulation No 6/2002 already ensure such protection. It should be borne in mind that the provisions in Article 25(1)(b) and in Article 25(1)(e) of Regulation No 6/2002 provide for two separate grounds for invalidity. With regard to the legislation on trade marks, the applicant does not adduce evidence in support of its claim.

84 The fourth plea in law must consequently be rejected without it being necessary to rule on the plea of inadmissibility raised by OHIM at the hearing.

The fifth plea in law, alleging an error of law vitiating the rejection of the request for proof of genuine use of the earlier mark

85 In the context of the present plea, too, the applicant’s arguments correspond to those put forward in support of the second plea in law in the case giving rise to the Instrument for writing judgment. The applicant submits that it follows from Article 25(1)(e) of Regulation No 6/2002, read in conjunction with Paragraph 25 of the Markengesetz, that, where the proprietor of a German trade mark applies for a declaration of invalidity in respect of a Community design on the ground that use is made of the mark in the design in question, that proprietor must, if challenged on the point, demonstrate that it has made genuine use of the mark. Consequently, the Board of Appeal ought to have examined the applicant’s request made before it for proof of use of the earlier mark.

86 Those arguments cannot be accepted.

87 As the Court held, in particular, in paragraphs 72 and 77 of the Instrument for writing judgment, the applicant had the right to submit a request before the Invalidity Division that the intervener be required adduce proof of genuine use of the earlier mark at issue; however, the applicant referred to the issue of proof of genuine use of that mark for the first time in the pleadings setting out the grounds for its appeal before the Board of Appeal. Even assuming that those pleadings could be construed as containing a request for proof of genuine use of the earlier mark at issue, a request of that kind, made for the first time before the Board of Appeal, is inadmissible and cannot be taken into consideration and examined by the Board of Appeal. The Board of Appeal set out that finding in the contested decision (paragraph 24).

88 In the present case, the applicant claims, furthermore, that the request for proof of genuine use, submitted before the Board of Appeal, was not submitted under Article 43(2) and (3) of Council Regulation (EC) No 40/94 of 20 December 1993 on the Community trade mark (OJ 1994 L 11, p. 1), as amended (now Article 42(2) and (3) of Council Regulation (EC) No 207/2009 of 26 February 2009 on the Community trade mark (OJ 2009 L 78, p. 1) and that the case-law relating to that article should not apply. In the applicant’s opinion, its request ought to have been examined as a late filed argument under general principles.

89 That issue has also already been examined in the Instrument for writing judgment, in which it was held that, since no specific provision is made in Regulation No 6/2002 concerning the procedure for requesting proof of genuine use of the earlier sign, to be followed by the proprietor of the Community design in respect of which an application for a declaration of invalidity has been brought on the basis of the earlier sign, that request had to be submitted to OHIM expressly and in due time, that is to say, in principle, within the period of time granted by the Invalidity Division to the proprietor of the Community design for submitting its observations in response to that application (Instrument for writing judgment, paragraph 67). That finding must also be applied in the present case.

90 As the Court noted in paragraphs 69 and 71 of the Instrument for writing judgment, the case-law based on Article 42(2) and (3) of Regulation No 207/2009 applies also, by analogy, to requests for proof of genuine use made in the context of invalidity proceedings in accordance with Article 25(1)(e) of Regulation No 6/2002, because in this context, too, it is unacceptable that the Board of Appeal could be put in the position of having to rule on a dispute which is different from the dispute brought before the Invalidity Division, that is to say, a dispute the scope of which has been extended through the addition of the preliminary issue of genuine use of the earlier sign relied on in support of the application for a declaration of invalidity.

91 Consequently, the fifth plea in law must be rejected without it being necessary to rule on the plea of inadmissibility raised by OHIM at the hearing.

The sixth plea in law, alleging incorrect application of Article 25(1)(e) of Regulation No 6/2002

92 First, according to the applicant, the Board of Appeal failed to examine the extent to which the contested Community design and the earlier three-dimensional mark were similar. However, the examination of the degree of similarity is, it argues, essential to the global assessment of the likelihood of confusion.

93 This argument of the applicant is factually incorrect and must be rejected. In paragraph 41 of the contested decision, the Board of Appeal held that the products in which the contested design was intended to be incorporated were identical to those covered by the earlier three-dimensional mark (see also paragraph 47 of the contested decision).

94 Furthermore, in paragraph 43 of the contested decision, the Board of Appeal found that the differences between the contested Community design and the earlier three-dimensional mark essentially concerned the surface of the highlighter pen, but did not alter its overall shape. In its opinion, the public pays less attention to the particular design of the highlighter’s surface and more attention to its overall shape. The Board of Appeal concluded that the earlier three-dimensional mark and the contested Community design were therefore similar.

95 Consequently, it must be held that the Board of Appeal found a sufficiently high degree of similarity in order to be able validly to hold that there was a likelihood of confusion between the earlier three-dimensional mark and the contested Community design.

96 Furthermore, it follows from settled case-law that the global assessment of the likelihood of confusion implies some interdependence between the factors taken into account, in particular between the similarity of the trade marks and that of the goods or services covered. Accordingly, a lesser degree of similarity between the goods or services designated may be offset by a greater degree of similarity between the marks and vice versa (see, by analogy, judgment of 22 September 2011 in Case T‑174/10 ara v OHIM — Allrounder (A with two triangular motifs), not published in the ECR, paragraph 33 and the case-law cited). It follows from the contested decision, read as a whole, that the Board of Appeal had not taken the view that the degree of similarity between the earlier three-dimensional mark and the contested Community design was weak.

97 Secondly, the applicant claims that the Board of Appeal disregarded the substantial surface differences existing on the contested design and that it focused almost entirely on the fact that the overall shape was essentially similar.

98 In this regard, it is apparent from settled case-law that the question whether a likelihood of confusion exists on the part of the public must be assessed globally, taking account of all factors relevant to the circumstances of the case (see, by analogy, Case C‑251/95 SABEL [1997] ECR I‑6191, paragraph 22; Case C‑342/97 Lloyd Schuhfabrik Meyer [1999] ECR I‑3819, paragraph 18; and Case C‑120/04 Medion [2005] ECR I‑8551, paragraph 27).

99 The global assessment of the likelihood of confusion, in terms of the visual, aural or conceptual similarity of the signs at issue, must be based on the overall impression given by those signs, account being taken, in particular, of their distinctive and dominant components. The perception of the signs in the mind of the average consumer of the goods or services in question plays a decisive role in the global assessment of that likelihood of confusion. In this regard, the average consumer normally perceives a mark or other distinctive sign as a whole and does not proceed to analyse its various details (see, to that effect and by analogy, SABEL, paragraph 23; Lloyd Schuhfabrik Meyer, paragraph 25; and Medion, paragraph 28).

100 In the present case, and as has been noted in paragraph 94 above, the Board of Appeal held that, visually, ‘the differences between the contested [Community design] and the trade mark [were] insufficient to prevent features of the trade mark from being discernible in the contested [design]. They essentially concern[ed] the surface of the highlighter pen but [did] not alter its overall shape. [The Board of Appeal] held that small surface interruptions [were] common for writing instruments as a means to enhance their grip. Consequently, [it held that] the public [paid] less attention to the particular design of the highlighter’s surface and more attention to its overall shape. The earlier [three-dimensional] mark and the contested [design were] therefore considered similar’ (paragraph 43 of the contested decision).

101 It must be concluded that the Board of Appeal assessed the contested design in global terms and that it found that the relevant public would perceive the surface features of that design as a means to enhance the grip of the product. As has been observed in paragraph 75 above, it is precisely because of those surface differences that the Board of Appeal concluded that the contested design and the earlier three-dimensional mark were similar and not identical. Likewise, in the assessment of the novelty and distinctive character of the contested design, the Board of Appeal held that the differences highlighted by the applicant could not be described as insignificant, but that they were not sufficient to influence the overall impression that the designs concerned had on the informed user. It follows that the Board of Appeal did indeed take account the differences concerned, but that it took the view that they would not affect the general perception. Consequently, the contested decision is not vitiated by illegality in that regard.

102 Third, the applicant claims that the Board of Appeal reversed the burden of proof, since, in accordance with the case-law, it is for the intervener to establish the existence of a risk of confusion and not for the applicant to show that there was no likelihood of confusion. The applicant argues, however, that the double negative in paragraph 48 of the contested decision shows clearly that the burden of proof was reversed.

103 That argument must be rejected. In paragraph 48, the Board of Appeal examined solely the specific question of the distinctive character of the earlier three-dimensional mark and held in that regard that, ‘[t]aking into account the similarity of the contested [design] and the earlier [three-dimensional] mark and the identity of the products in which the design is intended to be incorporated and the earlier mark’s goods, even a low degree of distinctiveness of the earlier trade mark would not suffice to exclude a likelihood of confusion’. It therefore found positively that there was a likelihood of confusion independently of the degree of the distinctive character of the earlier three-dimensional mark. It concluded, in paragraph 49 of the contested decision, that it was therefore not necessary to examine that distinctive character in order to be able to find that there was a likelihood of confusion.

104 In the light of the foregoing, the sixth plea in law must be rejected.

The seventh plea in law, alleging incorrect application of Article 25(1)(b) of Regulation No 6/2002

105 The applicant claims that, in the context of the examination of the novelty and individual character of the contested design, the Board of Appeal incorrectly assessed the characteristics of the informed user, and the method and way in which the examination of the overall impression should be carried out.

106 It follows from the case-law that, in an action for annulment, a plea in law is held to be ineffective which, even in the event that it were well founded, would be inappropriate to lead to the annulment sought by an applicant (see, to that effect, Case C‑46/98 P EFMA v Council [2000] ECR I‑7079, paragraph 38; see also, to that effect, the Opinion of Advocate General Mengozzi in Case C‑401/09 P Evropaïki Dynamiki v ECB [2011] ECR I‑4911, point 87).

107 In the present case, even if it is assumed that the present plea in law is well founded, the applicant cannot, in any event, secure annulment of the contested decision, as the first six pleas in law relating to the first ground for invalidity have been rejected. Since the Board of Appeal declared the contested design to be invalid on the grounds referred to in Article 25(1)(e) and in Article 25(1)(b) of Regulation No 6/2002, the first ground continues to substantiate the operative part of that decision. Consequently, the seventh plea in law must be rejected as ineffective.

108 It follows from all of the foregoing that the action must be dismissed in its entirety.

Costs

109 Under Article 87(2) of the Rules of Procedure of the General Court, the unsuccessful party is to be ordered to pay the costs if they have been applied for in the successful party’s pleadings.

110 Since the applicant has been unsuccessful, it must be ordered to pay the costs, in accordance with the forms of order sought by OHIM and the intervener.

On those grounds,

THE GENERAL COURT (Seventh Chamber)

hereby:

1. Dismisses the action;

2. Orders Beifa Group Co. Ltd to pay the costs.

Dittrich | Wiszniewska-Białecka | Prek |

Delivered in open court in Luxembourg on 27 June 2013.

[Signatures]