JUDGMENT OF THE GENERAL COURT (First Chamber)

14 June 2012 (*)

(Community trade mark – Application for Community mark representing seven squares of different colours – Sign of which a Community trade mark may consist – Article 4 of Regulation (EC) No 207/2009)

In Case T‑293/10,

Seven Towns Ltd, established in London (United Kingdom), represented by E. Schäfer, lawyer,

applicant,

v

Office for Harmonisation in the Internal Market (Trade Marks and Designs) (OHIM), represented by D. Botis, acting as Agent,

defendant,

ACTION brought against the decision of the First Board of Appeal of OHIM of 29 April 2010 (Case R 1475/2009-1), concerning an application for registration of a sign representing seven squares of different colours as a Community mark,

THE GENERAL COURT (First Chamber),

composed of J. Azizi, President, F. Dehousse and S. Frimodt Nielsen (Rapporteur), Judges,

Registrar: S. Spyropoulos, Administrator,

having regard to the application lodged at the Registry of the General Court on 6 July 2010,

having regard to the response lodged at the Court Registry on 15 November 2010,

having regard to the reply lodged at the Court Registry on 22 February 2011,

having regard to the rejoinder lodged at the Court Registry on 15 June 2011,

having regard to the designation of another judge to complete the Chamber as one of its members was prevented from attending,

further to the hearing on 20 March 2012,

gives the following

Judgment

Background to the dispute

1 On 17 January 2007, the applicant, Seven Towns Ltd, filed an application for registration of a Community trade mark at the Office for Harmonisation in the Internal Market (Trade Marks and Designs) (OHIM), under Council Regulation (EC) No 40/94 of 20 December 1993 on the Community trade mark (OJ 1994 L 11, p. 1), as amended (replaced by Council Regulation (EC) No 207/2009 of 26 February 2009 on the Community trade mark (OJ 2009 L 78, p. 1)).

2 The mark in respect of which registration was applied for is, according to the information provided by the applicant, a ‘colour mark per se’.

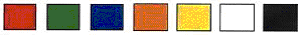

3 The applicant provided the following information under the heading ‘Indication of colours’:

1. Red (PMS 200C)

2. Green (PMS 347C)

3. Blue (PMS 293C)

4. Orange (PMS 021C)

5. Yellow (PMS 012C)

6. White (white)

7. Black (black)

4 The applicant also provided the following description:

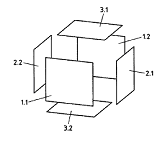

‘Six surfaces being geometrically arranged in three pairs of parallel surfaces, with each pair being arranged perpendicularly to the other two pairs characterised by: (i) any two adjacent surfaces having different colours and (ii) each such surface having a grid structure formed by black borders dividing the surface into nine equal segments.’

5 The goods in respect of which registration was applied for are in Class 28 of the Nice Agreement of 15 June 1957 concerning the International Classification of Goods and Services for the Purposes of the Registration of Marks, as revised and amended, and correspond to the following description: ‘Toys, games, playthings and jigsaw puzzles, three dimensional puzzles, electronic games; hand-held electronic games’.

6 By letter of 13 April 2007, the examiner informed the applicant that examination of the application had been successfully completed and that the application would shortly be published in the Community Trade Marks Bulletin. That letter also stated that OHIM reserved the right to reopen the examination procedure if new aspects arose.

7 By letter of 30 July 2007, the examiner informed the applicant that its application would be published in Community Trade Marks Bulletin No 38/2007 of 30 July 2007, as it subsequently was.

8 By letter of 9 August 2007, the examiner informed the applicant that OHIM had corrected the indication of the nature of the mark applied for from ‘colour’ mark to ‘figurative’ mark, as it was apparent from the representation of the mark attached to the application that the mark applied for was a figurative mark in colours and not a colour mark per se. Also in that letter, the examiner informed the applicant that the description of the mark attached to the application did not correspond to the representation of the mark applied for and that OHIM’s intention was therefore to delete the description, unless the applicant wished to submit a new one.

9 By fax of the same day sent to OHIM, the applicant objected to the approach proposed by the examiner, arguing that OHIM could no longer make such modifications after the publication of the application. In the absence of a reaction, the applicant sent OHIM reminders on 15 April, 27 June and 16 September 2008. On 5 June 2009, the applicant also wrote to OHIM’s complaints department and, on 11 August 2009, to the director of the trade marks department at OHIM.

10 By letter to the applicant of 10 September 2009, the examiner repeated its objection made on 9 August 2007 which was based on the discrepancy between the graphic representation and the description of the mark applied for. In that letter, the examiner also observed that the sign at issue does not represent a combination of colours per se, but a juxtaposition of coloured squares characterised by a particular size, form and order and that, on that ground, the mark must be deemed to be a figurative mark and not a colour mark. The examiner referred, in that regard, to OHIM’s Manual of Trade Mark Practice which states that the representation of a colour mark per se must consist of a representation of the colour(s) without contour. The examiner also stated that, according to case-law, a colour per se implies that it is not spatially delimited.

11 On 24 September 2009, the applicant again stressed its desire to register a colour mark per se and stated that, in its view, the sign complies with Article 4 of Regulation No 207/2009.

12 By decision of 2 November 2009, the examiner rejected the application on the ground that the representation of the mark applied for did not satisfy the requirements set out in Article 4 of Regulation No 207/2009.

13 On 30 November 2009, the applicant filed a notice of appeal against that decision with OHIM, pursuant to Articles 58 to 64 of Regulation No 207/2009.

14 By decision of 29 April 2010 (Case R 1475/2009-1) (‘the contested decision’), the First Board of Appeal of OHIM annulled the examiner’s decision on the ground that he had infringed essential procedural requirements, and rejected the mark applied for under Article 4 of Regulation No 207/2009. The principal reasons for that decision will be set out below.

Forms of order sought

15 The applicant claims that the Court should:

– annul the contested decision;

– order OHIM to pay the costs.

16 OHIM contends that the Court should:

– dismiss the action;

– order the applicant to pay the costs.

Law

17 In support of its action, the applicant puts forward three pleas in law.

18 First, the applicant claims that, as too much time had elapsed between the examiner’s letters of 13 April 2007 and 10 September 2009, OHIM no longer had the right to reopen the examination procedure and the Board of Appeal could not therefore examine the substantive issues.

19 Second, the applicant submits that, by rejecting the application for registration on the basis of a completely new argument, rather than remitting the matter to the OHIM examiner, the Board of Appeal curtailed the applicant’s right to be heard.

20 Third, the applicant claims that the contested decision infringes Article 4 of Regulation No 207/2009 in so far as the Board of Appeal invented a test which had no proper legal basis and which, moreover, it misapplied and that the application complies with all formal requirements of Regulation No 207/2009 and Commission Regulation (EC) No 2868/95 of 13 December 1995 implementing Regulation No 40/94 (OJ 1995 L 303, p. 1).

The first plea in law, based on the time taken by the examiner to assess the application for registration

21 The applicant claims that, if OHIM wishes to revoke a prior decision and reopen the examination stage, it must follow the procedure provided for in Article 80(1) and (2) of Regulation No 207/2009 which allows for the revocation of a decision which contains a procedural error within six months from the date the decision was taken, and in Rule 53a of Regulation No 2868/95 which requires OHIM to inform the party affected of the error so that the affected party may submit observations.

22 However, in the present case, it is first of all apparent from the examiner’s letter of 13 April 2007 that the examination stage for the application for registration had been completed by that date. That indication was confirmed by the examiner’s letter of 30 July 2007 which also stated that the application had been accepted for publication. Those two letters constitute formal notification of the fact that OHIM failed to find any absolute ground for refusal which would prevent the application from proceeding to the next stage of the registration procedure, that is to say publication and the opposition period. OHIM is bound by those statements unless new information is brought to its notice.

23 Moreover, the examiner’s letter of 9 August 2007 may not be considered to be a re-opening of the examination procedure. That letter did not state that OHIM intended to revoke, as defined in Article 80 of Regulation No 207/2009, the decisions previously adopted in its letters of 13 April and 30 July 2007 in order to re‑open the examination procedure. The rectification of the application for registration of the mark from ‘colour per se’ to ‘figurative’, as indicated in the letter of 9 August 2007, is also unlawful.

24 It was only by the letter of 10 September 2009 that the applicant learned of the examiner’s objections concerning the application for registration. OHIM had remained inactive for too long. While OHIM may rectify the errors as part of an ordered procedure, such discretion should not be exercised for an indeterminate period. At such a late stage, that is to say more than two years after the closure of the examination procedure and the issuance of a notice of publication, the Board of Appeal could not examine the substantive issues, previously examined under the examination procedure which was formally completed by the letters of 13 April and 30 July 2007, and should have considered that the examination procedure could no longer be validly re-opened.

25 In response to that line of argument, the Court notes at the outset that, in recitals 12 and 13 of the contested decision, the Board of Appeal decided to annul the examiner’s decision of 2 November 2009 against which the applicant had brought an appeal. The Board of Appeal’s reasoning in that regard is as follows:

‘(12) The applicant is right to criticise the manner in which the application was dealt with by [OHIM]. The facts speak for themselves. [OHIM] published the application for a colour mark in [Community Trade Marks Bulletin] No 38/2007 on 30 July 2007, but then decided of its own motion to reclassify the mark [as a figurative mark] on 8 August 2007 [and to delete the description of the mark], which had not previously attracted any objection. The applicant immediately objected but was met with silence on the part of [OHIM], which, despite a number of reminders, took no further action until 10 September 2009. In the letter of that date the examiner confirmed that the application would be accepted if the applicant amended the type of mark from “colour per se” to “figurative”. The application was finally refused on 2 November 2009 on the basis of Article 4 [of Regulation No 207/2009]. That provision had not, however, been mentioned by the examiner in the previous correspondence. The letter of 10 September 2009 had referred to [OHIM’s] Manual of Trade Mark Practice and to the Libertel judgement but had not mentioned Article 4 [of Regulation No 207/2009].

(13) The applicant rightly points out that if [OHIM] thought it necessary to revoke the decision to publish the application it should have followed the procedure laid down in Article 80 [of Regulation No 207/2009]. The failure to follow that procedure and the refusal of the application under Article 4 [of Regulation No 207/2009] without previously inviting the applicant to comment on the correct application of Article 4 constitute serious procedural violations which justify the annulment of the contested decision…’

26 In the present case, the examination by the Court thus concerns the legality of the contested decision adopted by the Board of Appeal, which the applicant seeks to have annulled, and not the legality of the examiner’s decision which had previously been annulled by the Board of Appeal. This was acknowledged by the parties at the hearing.

27 In that respect, the applicant stated that its argument must be understood as meaning that, at the stage when the Board of Appeal ruled on the matter, it had no alternative but to follow the procedure set out in Article 80(1) and (2) of Regulation No 207/2009, according to which:

‘(1) Where the Office has made an entry in the Register or taken a decision which contains an obvious procedural error attributable to the Office, it shall ensure that the entry is cancelled or the decision is revoked. Where there is only one party to the proceedings and the entry or the act affects its rights, cancellation or revocation shall be determined even if the error was not evident to the party.

(2) Cancellation or revocation as referred to in paragraph 1 shall be determined, ex officio or at the request of one of the parties to the proceedings, by the department which made the entry or took the decision. Cancellation or revocation shall be determined within six months from the date on which the entry was made in the Register or the decision was taken, after consultation with the parties to the proceedings and any proprietor of rights to the Community trade mark in question that are entered in the Register.’

28 Therefore, it claims, since the Board of Appeal did not formally revoke the ‘decisions previously adopted in [the examiner’s] letters of 13 April and 30 July 2007’, it was not able to rule on the application for registration. As more than six months has passed since the ‘decisions’ were taken, OHIM cannot revoke them and the Board of Appeal should have found that at such a late stage, that is to say more than two years after the closure of the examination procedure carried out by the examiner and the issuance of a notice of publication, the examination procedure could no longer be validly re-opened (see paragraph 24 above).

29 The applicant’s argument is thus based on the claim that it is not possible for the Board of Appeal to rule on the procedural and substantive issues relating to the application for registration of the mark applied for in view of the duration of the examination procedure before the examiner and the different stances adopted in that regard. In such a situation, the applicant claims that it has therefore, in a sense, an acquired right to registration of its mark.

30 However, it must be found that there is no such right.

31 From a legal point of view, the applicant has not put forward any relevant legal basis in support of its claim that the Board of Appeal could no longer give a ruling in the contested decision on whether the sign applied for is capable of constituting a Community trade mark within the meaning of Article 4 of Regulation No 207/2009.

32 On the contrary, Article 7 of that regulation expressly states that signs which do not conform to the requirements of Article 4 are not to be registered. It is an absolute ground for refusal and can be assessed at any time during the registration procedure provided that the applicant’s right to be heard is respected, an issue which will be examined in the context of the second plea in law.

33 Moreover, it must be observed that publication of a trade mark application is no guarantee that the mark concerned will be registered. It is clear from Article 39(2) of Regulation No 207/2009 that, following its publication, the trade mark application may still be refused under Article 37 of the regulation, which provides for an examination as to absolute grounds for refusal (see, to that effect, Case T‑289/02 Telepharmacy Solutions v OHIM (TELEPHARMACY SOLUTIONS) [2004] ECR II‑2851, paragraph 60).

34 From a factual point of view, the applicant cannot therefore rely on the stance adopted by the examiner in the letters of 13 April and 30 July 2007 to support the claim that they are, in actual fact, decisions which may be amended only following completion of the revocation procedure provided for in Article 80(1) and (2) of Regulation No 207/2009. Those letters only inform the applicant of the state of progress of the examination procedure of the application for registration and do not establish an acquired right to registration for the applicant. The only decisive measure in that regard is that which was adopted at the end of the examination procedure, that is to say, in the present case, the examiner’s decision of 2 November 2009 which was annulled following an appeal brought by the applicant.

35 Accordingly, when the examiner informed the applicant, on 13 April 2007, that examination of its application had been successfully completed, this did not prevent OHIM, that is to say the examiner or ultimately the Board of Appeal, from deciding at a later date, and even more than six months from that notification, that there is an absolute ground for refusal in respect of the sign for which registration is sought, which means that registration must be refused.

36 Likewise, as was stated in paragraph 33 above, the fact that the examiner informed the applicant, on 13 April and again on 30 July 2007, that the application for registration was going to be published in the Community Trade Marks Bulletin was not a guarantee that the mark would be registered.

37 In that regard, and in any event, it must be noted that there is no sound evidence that, in the present case, the publication of the application for registration in the Community Trade Marks Bulletin had been or should have been revoked pursuant to the procedure under Article 80(1) and (2) of Regulation No 207/2009 invoked by the applicant. The unfortunate phrase in the examiner’s letter of 9 August 2007, by which the examiner informed the applicant that ‘[OHIM] has corrected the indication of the nature of the mark from “colour” to “figurative” ‘never had any effect. The publication of the application for registration in Community Trade Marks Bulletin No 38/2007 of 30 July 2007 states that the mark applied for is a colour mark. That publication was never amended in that regard, as the parties were able to confirm at the hearing. Moreover, the examiner subsequently withdrew it. In his letter of 10 September 2009, the examiner also informed the applicant, in place of what he envisaged in his letter of 9 August 2007, that there was a possibility of amending the type of mark from ‘colour per se’ to a ‘figurative mark’, which, according to the examiner, would imply an automatic acceptance of the application. The examiner’s announcement that OHIM had corrected, of its own motion, the indication at issue, thus ultimately became only a possibility of making an amendment, which OHIM itself may not have believed that it was entitled to do of its own motion. Likewise, in the examiner’s decision of 2 November 2009, he informed the applicant that his assessment was made in respect of the trade mark as applied for without making any changes in that regard. It is also clear from the contested decision that the Board of Appeal ruled on the application lodged by the applicant and published in the Community Trade Marks Bulletin, which indeed indicates that the mark applied for is a colour mark per se.

38 Nor may the applicant plead the principle of legitimate expectations to claim that the mark applied for should have been registered given the length of the examination procedure before the examiner, and the various positions adopted on 13 April and 30 July 2007. In accordance with settled case-law, the right to rely on that principle extends to any person with regard to whom an institution of the European Union has given rise to justified hopes. Moreover, a person may not plead infringement of the principle unless he has been given precise assurances by the administration (judgment of 24 November 2005 in Case C‑506/03 Germany v Commission, not published in the ECR, paragraph 58). In the present case, even if it were held that the positions adopted constituted precise assurances that gave rise to justified hopes on the part of the applicant, that could only be that the mark applied for would be published – which it was – but not that it would be registered upon completion of the examination procedure. There is nothing in the case-file to indicate that OHIM gave such assurances in that regard, in particular so far as concerns whether the sign referred to in the application for registration was capable of constituting a Community mark within the meaning of Article 4 of Regulation No 207/2009.

39 Consequently, however regrettable the excessive delay between the examiner’s letter of 13 April 2007 and that of 10 September 2009 may be, the time taken for the examiner to rule on an absolute ground for refusal based on Article 4 of Regulation No 207/2009 is not such as to prevent the Board of Appeal from dismissing the application for a Community mark on that basis.

40 In the light of the foregoing, the first plea in law must be rejected.

The second plea in law, based on the absence of remittal to the examiner and infringement of the right to be heard

41 The applicant claims that the grounds on which the Board of Appeal based the contested decision are different to the issues raised in the examiner’s letter of 9 August 2007. The Board of Appeal therefore adopted its decision on completely new grounds without giving the applicant any opportunity to comment. In the present case, the Board of Appeal should have applied Article 64(1) of Regulation No 207/2009 and remitted the case to the examiner. That would have enabled the applicant to submit its observations on whether, upon consulting the Community trade mark register, a reasonably observant person would be able to understand precisely what the mark consists of, without expending a huge amount of intellectual energy and imagination.

42 In that regard, the Court notes first of all that, in the contested decision, the Board of Appeal decided, given the amount of time that had already elapsed, to deal with the substance of the case directly rather than remitting it to the examiner (see recital 14 of the contested decision). That decision is consistent with Article 64(1) of Regulation No 207/2009 which provides that: ‘Following the examination as to the allowability of the appeal, the Board of Appeal shall decide on the appeal’ and ‘may either exercise any power within the competence of the department which was responsible for the decision appealed or remit the case to that department for further prosecution’. That provision therefore enables the Board of Appeal to exercise the functions of the examiner who adopted the decision at issue, as it did in the present case.

43 In such a situation, it is however for the Board of Appeal to ensure that the conditions set out in Article 37(3) of Regulation No 207/2009 and in Article 75 of that regulation have been respected. Under the first provision, the application for registration may not be refused until the applicant has been allowed the opportunity of submitting its observations. The second provision provides that decisions of OHIM must state the reasons on which they are based and must be based only on reasons or evidence on which the parties concerned have had an opportunity to present their comments. In that regard, it must be noted that the contested decision concludes that the application for registration must be rejected because it does not satisfy the requirements set out in Article 4 of Regulation No 207/2009, which constitutes an absolute ground for refusal of registration.

44 It is apparent from both the applicant’s reply of 24 September 2009 to the examiner and its appeal brought on 30 November 2009 against the examiner’s decision that the applicant was able to submit its observations on why the sign applied for was capable of constituting a Community mark in accordance with the requirements set out in Article 4 of Regulation No 207/2009. Those observations are largely the same as those submitted in the present action and concern, in essence, the question of how it is possible to describe a colour mark by referring to several colours.

45 It must also be noted that, following the examiner’s decision of 2 November 2009, the applicant was aware that OHIM considered that the way in which the sign was represented was neither precise, nor intelligible. That decision thus states that the sign applied for is not sufficiently clear, precise, easily accessible and intelligible in the light of what is required by Article 4 of Regulation No 207/2009. That conclusion is comparable to that reached by the Board of Appeal in the contested decision.

46 The applicant cannot therefore claim that it did not have the opportunity in the present case to comment on the absolute ground for refusal contemplated by OHIM as a reason for refusing registration of the mark applied for. Furthermore, and in any event, the Board of Appeal cannot be required to inform the parties in advance of how it intends to apply the law (Case T‑198/00 Hershey Foods v OHIM (Kiss Device with plume) [2002] ECR II‑2567, paragraphs 23 and 24; Case T‑16/02 Audi v OHIM (TDI) [2003] ECR II‑5167, paragraph 75; and Case T‑303/03 Lidl Stiftung v OHIM – REWE-Zentral (Salvita) [2005] ECR II‑1917, paragraph 62).

47 In the present case, in the light of the circumstances referred to in paragraphs 43 to 45 above, the Board of Appeal satisfied the procedural requirements incumbent upon it in the present case.

48 In the light of the foregoing, the second plea in law must be rejected.

The third plea in law, alleging infringement of Article 4 of Regulation No 207/2009

49 The applicant claims that its application satisfied the requirements set out in Article 4 of Regulation No 207/2009, as interpreted by the case-law. Under that provision, ‘a Community trade mark may consist of any signs capable of being represented graphically, particularly words, including personal names, designs, letters, numerals, the shape of goods or of their packaging, provided that such signs are capable of distinguishing the goods or services of one undertaking from those of other undertakings’.

50 Consequently, in order to constitute a mark, a sign must be able to be represented graphically, particularly by means of images, lines or characters, and the representation must be clear, precise, self-contained, easily accessible, intelligible, durable and objective (Case C‑273/00 Sieckmann [2002] ECR I‑11737, paragraph 55). Accordingly, a graphic representation consisting of two or more colours, designated in the abstract and without contours, must be systematically arranged by associating the colours concerned in a predetermined and uniform way (Case C‑49/02 Heidelberger Bauchemie [2004] ECR I‑6129, paragraph 33).

51 In the present case, the applicant submits that the Board of Appeal adopted a misconceived test in the contested decision, where it states, in recital 17, that the test ‘is whether a reasonably observant person with normal levels of perception and intelligence would, upon consulting the Community trade mark register, be able to understand precisely what the mark consists of, without expending a huge amount of intellectual energy and imagination’. According to the applicant, it is obvious that the description of a colour mark per se is abstract. That such a description must be self-contained, complete and coherent is also obvious. Applying additional criteria is inappropriate. The criteria ‘normal levels of perception and intelligence’ or ‘huge amount of intellectual energy and imagination’ are not legal terms. Those criteria are without a sufficiently precise meaning and the outcome of their application is unpredictable.

52 Moreover, the applicant claims that the aforementioned test was wrongly applied by the Board of Appeal, as is shown by the following demonstration:

‘…

Six surfaces being geometrically arranged in three pairs of parallel surfaces, with each pair being arranged perpendicularly to the other two pairs

characterised by

(i) any two adjacent surfaces having different colours and

(ii) each such surface having a grid structure formed by black borders dividing the surface into nine equal segments

…’

53 According to the applicant, any person with basic notions of geometry should understand that a surface having a grid structure formed by black borders dividing the surface into nine equal segments is a 3x3 square surface. Three pairs of square surfaces are six square surfaces, etc. Moreover, it is clearly stated how the colour black is arranged in relation to the other ‘real’ colours. Thus the description is self-contained, complete and coherent in the sense of being clear, precise and intelligible. Even with hindsight it is more than difficult to come up with a description of the colour mark per se which is less abstract, more concise or much easier to understand than the description at hand. Moreover, if one sees the Community colour mark per se applied on the product as according to the description, it would be perfectly simple to match the description with what one sees.

54 In response to that line of argument, the Court must note that, in the contested decision, the Board of Appeal decided to reject the applicant’s application for registration on the ground that it did not satisfy the requirements set out in Article 4 of Regulation No 207/2009 (see recitals 15 to 19 of the contested decision).

55 As regards the analysis of the sign applied for under Article 4 of Regulation No 207/2009, the Board of Appeal stated, in recital 15 of the contested decision, that, in accordance with settled case-law, the principal purpose of the requirements laid down in Article 4 of Regulation No 207/2009 is to ensure that the trade mark register contains clear, precise and easily accessible information about the signs that are protected through registration, so that other traders are able to find out what signs are protected and adjust their conduct accordingly.

56 In recital 16 of the contested decision, the Board of Appeal stated that the graphic representation of a sign must be clear, concise, self-contained, easily accessible, intelligible, durable and objective, that, in the case of a colour mark per se, a sample of the colour together with a verbal description of the colour and an internationally recognised code may constitute a proper graphic representation, and that, where the mark applied for consists of two or more colours, designated in the abstract and without contours, the graphic representation must be systematically arranged by associating the colours in a predetermined and uniform way.

57 In applying those principles to the facts of the present case, the Board of Appeal held, in recital 17 of the contested decision, that the sign applied for does not comply with the requirements set out in Article 4 of Regulation No 207/2009, on the ground that a ‘reasonably observant person with normal levels of perception and intelligence’ would, ‘upon consulting the Community trade mark register’, be unable ‘to understand precisely what the mark consists of, without expending a huge amount of intellectual energy and imagination’. According to the Board of Appeal, persons who consulted the register and saw the information set out in paragraphs 2 to 4 above would be unlikely to understand with the necessary degree of certainty what sign the applicant wishes to protect. Those persons would infer from the designation ‘colour mark’ that protection is claimed for a colour or combination of colours per se. They would see from the applicant’s ‘indication of colours’ that seven colours (including black and white) are involved. For the Board of Appeal, ‘it is highly likely that [persons who consulted the register and saw the information set out in paragraphs 2 to 4 above] would, like the examiner, be confused and see a contradiction between the reference to six surfaces and the claim of seven colours’ and that ‘most people would be left scratching their heads and wondering what exactly this strange and mysterious trade mark was’.

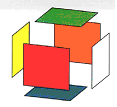

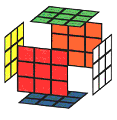

58 Moreover, the Board of Appeal observed that it is highly unlikely that anyone would infer from the information set out in paragraphs 2 to 4 above that the trade mark application had anything to do with the world-famous puzzle known as Rubik’s cube, in respect of which the applicant is the proprietor of a Community three-dimensional trade mark which was published with a description that is substantially the same as the description set out in paragraph 4 above. Consequently, while the Board of Appeal may conclude that the trade mark applied for in the present case is related to Rubik’s cube and that the aforementioned description is intended to describe the systematic arrangement of colours used on Rubik’s cube, the Board of Appeal indicates that it is only able to reach that conclusion as a result of the aforementioned additional information, that is to say after being given some very strong clues about the true nature of the mark applied for. Without those clues and solely on the basis of the information set out in paragraphs 2 to 4 above, the Board of Appeal is of the opinion that ‘a reasonably observant person would not realise that the colour mark applied for in the present case relates to the colour scheme used on the classic version of Rubik’s cube’, which enables it to conclude that ‘[t]he applicant has failed to provide a graphic representation that is clear, concise, easily accessible and intelligible’.

59 Before addressing the applicant’s criticisms of the actual result of the examination set out in the contested decision, it must be noted that the Board of Appeal’s statement in recital 17 of that decision, according to which the examination was undertaken from the point of view of a ‘reasonably observant person with normal levels of perception and intelligence’, must be read by reference to the previous statement, in recital 15, that the category of persons concerned refers in particular to ‘other traders’ who must be able to know the precise scope of the protection granted to the marks already in the register. The entry of the mark in a public register has the aim of making it accessible to the competent authorities and to the public, particularly to economic operators (Heidelberger Bauchemie, cited above in paragraph 50, at paragraph 28), and the persons concerned must therefore be able to find out what signs are protected and adjust their conduct accordingly. As no reason has been put forward in the present case to justify particular characteristics of the consumers or traders concerned, the Board of Appeal’s reference, in recital 17 of the contested decision, to ‘normal levels of perception and intelligence’ is to be interpreted as meaning that the persons concerned are average consumers and traders.

60 So far as concerns the result of the examination carried out in the light of the perception of those persons, it must be held that the Board of Appeal’s conclusion that that category of persons must ‘be able to understand precisely what the mark consists of, without expending a huge amount of intellectual energy and imagination’ merely reflects the requirements of the case-law that in order to constitute a trade mark a sign must be capable of being represented graphically, particularly by means of images, lines or characters, and the representation must be clear, precise, self-contained, easily accessible, intelligible, durable and objective (Sieckmann, cited above in paragraph 50, at paragraph 55). In order to fulfil its role as a registered trade mark, a sign must always be perceived unambiguously and uniformly, so that the function of mark as an indication of origin is guaranteed (Heidelberger Bauchemie, cited above in paragraph 50, at paragraph 31).

61 Consequently, the examination carried out by the Board of Appeal in the contested decision is not unlawful or legally inadequate as the applicant claims (see paragraph 51 above).

62 As regards the application of the aforementioned principles to the facts of the present case, the Board of Appeal was right to find that the applicant has failed to provide in its application for registration a graphic representation of the mark applied for that is clear, concise, easily accessible and intelligible.

63 Thus, as indicated in recital 16 of the contested decision, the mode of representation of coloured squares is clearly incompatible with the requirements concerning colour marks per se in so far as all the squares (except the black square) have a black border, that is to say that they do not consist of colours designated in the abstract and without contours (Heidelberger Bauchemie, cited above in paragraph 50, at paragraph 33). In the present case, the squares have a border in a different colour (see paragraph 3 above), which contradicts their qualification in the application as colours per se. That contradiction is enhanced by the fact that the colour black appears both in the borders of the square and on its own. It is not possible to understand whether the colour should be understood solely as a border or whether it is also claimed as a colour per se. Moreover, if the subsequent reference to six surfaces must be understood as referring to the first of those approaches, the qualification of black as a colour per se is incorrect, in so far as its sole function is to form a black border around the other colours, that is to say a concrete geometric form which is inherently figurative and therefore incompatible with the concept of colour per se.

64 Furthermore, the Board of Appeal was also right to state, in recital 17 of the contested decision, that, with regard to the description of the mark applied for, it is necessary to expend a ‘huge amount of intellectual energy and imagination’ in order to understand with the necessary degree of certainty what sign the applicant wishes to protect as a colour mark on account of a combination of colours per se. Even by combining the information in paragraphs 2 to 4 above and leaving aside the aforementioned problem, it is still possible not to arrive at a cube, as the applicant claims, but quite simply a rectangular parallelepiped, which also meets the description provided. It is only if it is stated that all of the faces are squares that it is clearly a cube; the applicant does not give that additional detail in its description.

65 Furthermore, as the Board of Appeal observed in recitals 18 and 19 of the contested decision, the problem linked to the graphic description of the sign applied for is accentuated by the fact that a comparable description to that given in the present case has been used by the applicant in the case of another mark of which it is the proprietor and which is claimed to be ‘three-dimensional’. Logically, it is difficult to understand how the same description may be applied to both a mark with a coloured form and to a colour mark per se. The thing for which the applicant seeks protection, according to its own representation and description, is nothing more than a certain number of coloured squares with black borders, arranged in a particular way and applied to a specific product.

66 In the light of those factors, a sign as so defined is not a colour mark per se but a three-dimensional mark, or figurative mark, which corresponds to the external appearance of a particular object with a specific form, that is to say a cube covered in squares with a particular arrangement of colours. Even if the description had been clear and easily intelligible – which it was not in the present case – it would in any event have contained an inherent contradiction so far as concerns the true nature of the sign at issue.

67 Consequently, the reason the application for registration of the mark is inadmissible in the present case is not so much the failure to represent one of the individual elements of the sign in accordance with Rule 3 of Regulation No 2868/95, as the wrong, unclear and contradictory way in which those elements have been referred to and combined, as well as the incompatibility of that combination with the concept of a colour mark per se. The Board of Appeal was therefore right to find that the overall description of the mark was ambiguous and contradictory.

68 In the light of the foregoing, the third plea in law must be rejected.

69 Accordingly, the action must be dismissed in its entirety.

Costs

70 Under Article 87(2) of the Rules of Procedure of the Court, the unsuccessful party is to be ordered to pay the costs if they have been applied for in the successful party’s pleadings. Under Article 87(3) of the Rules of Procedure, the Court may order that, where the circumstances are exceptional, each of the parties should bear its own costs.

71 Given the failure of OHIM to respond between 9 August 2007, the date on which the applicant responded by fax to the examiner’s letter of 9 August 2007, and 10 September 2009, the date on which the examiner sent a new letter to the applicant, and taking account of the numerous requests made by the applicant during that period for OHIM to respond, the Court finds that it is appropriate in the present case to rule that, even though the applicant has been unsuccessful and OHIM has sought an order that the applicant pay the costs, each party should bear its own costs.

On those grounds,

THE GENERAL COURT (First Chamber)

hereby:

1. Dismisses the action;

2. Orders each party to bear its own costs.

Azizi | Dehousse | Frimodt Nielsen |

Delivered in open court in Luxembourg on 14 June 2012.

[Signatures]