JUDGMENT OF THE GENERAL COURT (Fourth Chamber)

7 February 2012 (*)

(Community trade mark — Invalidity proceedings — Community figurative mark representing elephants in a rectangle — Earlier international and national figurative marks representing an elephant and earlier national word mark elefanten — Relative ground of refusal — Likelihood of confusion — Similarity of the signs — Article 8(1)(b) of Regulation (EC) No 207/2009 — Distinctive character of the earlier marks)

In Case T‑424/10,

Dosenbach-Ochsner AG Schuhe und Sport, established in Dietikon (Switzerland), represented by O. Rauscher, lawyer,

applicant,

v

Office for Harmonisation in the Internal Market (Trade Marks and Designs) (OHIM), represented by G. Mannucci, acting as Agent,

defendant,

the other party to the proceedings before the Board of Appeal of OHIM, intervener before the General Court, being

Sisma SpA, established in Mantova (Italy), represented by F. Caricato, lawyer,

intervener,

ACTION against the decision of the Fourth Board of Appeal of OHIM of 15 July 2010 (Case R 1638/2008‑4) concerning invalidity proceedings between Dosenbach-Ochsner AG Schuhe und Sport and Sisma SpA,

THE GENERAL COURT (Fourth Chamber),

composed of I. Pelikánová (Rapporteur), President, K. Jürimäe and M. van der Woude, Judges,

Registrar: E. Coulon,

having regard to the application lodged at the Registry of the General Court on 18 September 2010,

having regard to the response of OHIM lodged at the Registry of the Court on 23 February 2011,

having regard to the response of the intervener lodged at the Registry of the Court on 4 February 2011,

having regard to the decision of 28 April 2011 refusing leave to lodge a reply,

having regard to the fact that no application for a hearing was submitted by the parties within the period of one month from notification of closure of the written procedure, and having therefore decided, acting upon a report of the Judge‑Rapporteur, to give a ruling without an oral procedure, pursuant to Article 135a of the Rules of Procedure of the General Court,

gives the following

Judgment

Background to the dispute

1 The intervener, Sisma SpA, is the proprietor of the Community figurative mark registered under No 4279295 (‘the contested mark’), in respect of which an application for registration was filed with the Office for Harmonisation in the Internal Market (Trade Marks and Designs) (OHIM) on 9 February 2005 pursuant to Council Regulation (EC) No 40/94 of 20 December 1993 on the Community trade mark (OJ 1994 L 11, p. 1), as amended (replaced by Council Regulation (EC) No 207/2009 of 26 February 2009 on the Community trade mark (OJ 2009 L 78, p. 1)). The contested mark was registered on 30 November 2006 for, inter alia, goods in Classes 24 and 25 of the Nice Agreement of 15 June 1957 concerning the International Classification of Goods and Services for the Purposes of the Registration of Marks, as revised and amended, and corresponding, for each of those classes, to the following description:

– Class 24: ‘Textiles; elastic woven material; adhesive fabric for application by heat; fabric of imitation animal skins; woollen fabric; blankets; travelling rugs; table covers; textile articles; wallpaper of textile; handkerchiefs of textile; flags; serviettes of textile and non-woven textile fabrics; table mats of textile; table napkins of textile; synthetic fabrics for baby-changing’;

– Class 25: ‘Clothing for gentlemen, ladies and children in general, including clothing in leather; shirts; blouses; skirts; suits; jackets; trousers; shorts; jerseys; t-shirts; pyjamas; stockings; singlets; corsets; suspenders; underpants; brassieres; slips; hats; headscarves; ties; raincoats; overcoats; coats; swimming costumes; tracksuits; anoraks; ski pants; belts; fur coats; mufflers; gloves; dressing gowns; footwear in general, including slippers, shoes, sports shoes, boots and sandals; babies’ napkins of textile; babies’ bibs’.

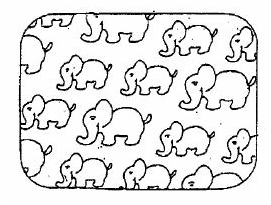

2 The contested mark is the following figurative sign:

3 On 20 February 2007 the applicant, Dosenbach-Ochsner AG Schuhe und Sport, filed with OHIM an application for a declaration of invalidity of the contested mark under Article 52(1)(a) of Regulation No 40/94 (now Article 53(1)(a) of Regulation No 207/2009).

4 The application for a declaration of invalidity related to the registration of the contested mark for the goods listed in paragraph 1 above. It was based on the existence of a likelihood of confusion within the meaning of Article 8(1)(b) of Regulation No 40/94 (now Article 8(1)(b) of Regulation No 207/2009) between that mark and the following earlier marks:

– the German word mark elefanten, applied for on 14 March 1987 and registered on 24 January 1989 under No 1133678, for goods in Class 25 and corresponding to the following description: ‘shoes’;

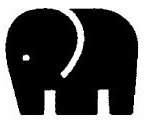

– the international figurative mark reproduced below, covering in particular the Czech Republic, registered on 29 May 1999, under No 715019, for goods in Class 25 and corresponding to the following description: ‘shoes and footwear’:

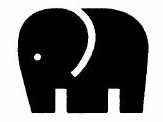

– the German figurative mark, reproduced below, applied for on 9 November 2000 and registered on 22 January 2001, under No 30082400, for, inter alia, ‘children’s blankets, children’s bedsheets, children’s face towels, children’s sleeping bags, textile bags and textile carriers for children’ in Class 24 and ‘children’s clothing, children’s headwear; children’s belts’ in Class 25:

5 By decision of 9 September 2008, the Cancellation Division of OHIM dismissed the application for a declaration of invalidity on the ground that there was no likelihood of confusion between the contested mark and the earlier marks. On 12 November 2008, the applicant filed a notice of appeal against the Cancellation Division’s decision.

6 By decision of 15 July 2010 (‘the contested decision’), the Fourth Board of Appeal of OHIM dismissed the appeal.

7 First, the Board of Appeal held, in paragraph 16 of the contested decision, that the relevant public was composed of average consumers, reasonably well‑informed and reasonably observant and circumspect, in Germany and in the Czech Republic.

8 Second, the Board of Appeal agreed, in paragraph 17 of the contested decision, with the Cancellation Division’s assessment that some of the goods covered by both the contested mark and the earlier marks were identical or similar, while others were different.

9 Third, the Board of Appeal took the view, in paragraphs 20 to 24 of the contested decision, that the contested mark was not visually similar to the earlier marks, taking into account in particular the differences between the representations of the figure of an elephant in the contested mark and in the earlier figurative marks.

10 Fourth, the Board of Appeal found, in paragraphs 25 to 27 of the contested decision, that the marks at issue were not phonetically similar, given that, first, figurative marks, including the contested mark, are not pronounced, and that, second, the oral descriptions of the marks concerned did not correspond.

11 Fifth, the Board of Appeal found, in paragraph 28 of the contested decision, that there was conceptual similarity resulting from the reference to an elephant in each of the marks concerned.

12 Sixth, in the context of the overall assessment of whether there was a likelihood of confusion, the Board of Appeal found, in paragraphs 30 to 39 of the contested decision, first, that the applicant had not claimed that the earlier marks had a particular distinctive character and, second, that, owing to the way in which the goods covered by the contested mark were marketed, greater importance had to be attached to a visual comparison. In those circumstances, the Board of Appeal concluded that the conceptual similarity found was not sufficient to create a likelihood of confusion between the contested mark and the earlier marks.

Forms of order sought

13 The applicant claims that the Court should:

– annul the contested decision;

– order OHIM to pay the costs.

14 OHIM contends that the Court should:

– dismiss the application;

– order the applicant to pay the costs.

15 The intervener contends, in essence, that the Court should:

– dismiss the application;

– order the applicant to pay the costs, including those relating to the proceedings before OHIM.

Law

16 The applicant raises a single plea alleging breach of Article 8(1)(b) of Regulation No 207/2009. Its claims, in essence, that the Board of Appeal committed errors of law and errors of assessment of the facts in concluding that there was no likelihood of confusion between the contested mark and the earlier marks.

17 Pursuant to Article 53(1)(a) of Regulation No 207/2009, a Community trade mark is to be declared invalid on application to OHIM where there is an earlier trade mark within the meaning of Article 8(2) of that regulation and, inter alia, the conditions set out in Article 8(1)(b) are fulfilled. Under that latter provision, upon opposition by the proprietor of an earlier trade mark, the trade mark applied for is not to be registered if, because of its identity with, or similarity to, the earlier trade mark and the identity or similarity of the goods or services covered by the trade marks, there exists a likelihood of confusion on the part of the public in the territory in which the earlier trade mark is protected. The likelihood of confusion includes the likelihood of association with the earlier trade mark. Moreover, under Article 8(2)(a)(ii) and (iii) of Regulation No 207/2009, the term ‘earlier trade marks’ is to be understood as meaning trade marks registered in a Member State and trade marks registered under international arrangements which have effect in a Member State, with a date of application for registration which is earlier than the date of application for registration of the Community trade mark.

18 According to settled case‑law, the risk that the public might believe that the goods or services in question come from the same undertaking or from economically‑linked undertakings constitutes a likelihood of confusion. According to that same line of case‑law, the likelihood of confusion must be assessed globally, according to the relevant public’s perception of the signs and goods or services concerned and taking into account all factors relevant to the circumstances of the case, in particular the interdependence between the similarity of the signs and that of the goods or services designated (see Case T‑162/01 Laboratorios RTB v OHIM — Giorgio Beverly Hills (GIORGIO BEVERLY HILLS) [2003] ECR II‑2821, paragraphs 30 to 33 and the case‑law cited).

19 In the present case, the applicant disputes neither the definition of the relevant public accepted by the Board of Appeal, as set out in paragraph 7 above, nor the examination of the similarity of the goods, referred to in paragraph 8 above. In so far as those findings are, moreover, not vitiated by any error, they must be taken into consideration in the examination of the present action.

20 By contrast, the applicant challenges, first, the assessment of the similarity of the signs, second, the failure to take into consideration the enhanced distinctiveness of the earlier marks and, third, the global assessment of whether there was a likelihood of confusion, taking into account in particular the relationship between the different elements of the comparison of the signs at issue.

21 OHIM and the intervener dispute the merits of the applicant’s arguments.

Comparison of the signs

22 The global assessment of the likelihood of confusion, in relation to the visual, phonetic or conceptual similarity of the signs in question, must be based on the overall impression given by the signs at issue, bearing in mind, inter alia, their distinctive and dominant elements. The perception of the marks by the average consumer of the goods or services in question plays a decisive role in the global assessment of that likelihood of confusion. In that regard, the average consumer normally perceives a mark as a whole and does not proceed to analyse its various details (see Case C‑334/05 P OHIM v Shaker [2007] ECR I‑4529, paragraph 35 and the case‑law cited).

23 Furthermore, according to settled case‑law, two marks are similar when, from the point of view of the relevant public, they are at least partially identical as regards one or more relevant aspects (Case T‑6/01 Matratzen Concord v OHIM — Hukla Germany (MATRATZEN) [2002] ECR II‑4335, paragraph 30, and judgment of 26 January 2006 in Case T‑317/03 Volkswagen v OHIM — Nacional Motor (Variant), not published in the ECR, paragraph 46).

24 In the present case, the applicant challenges the Board of Appeal’s findings with regard to the visual, phonetic and conceptual comparison of the marks concerned.

Visual comparison

25 In paragraphs 20 to 22 of the contested decision, the Board of Appeal found that the earlier marks comprised, on the one hand, the term ‘elefanten’ and, on the other hand, the stylised representation of a stocky Asian elephant, with very short legs, represented in profile. The contested mark, for its part, consisted of a rectangular label with rounded corners containing a number of African elephants of different sizes, represented in profile, with trunks slightly raised and organised in diagonal lines.

26 On the basis of those findings, the Board of Appeal concluded in paragraphs 22 and 24 of the contested decision that the marks concerned were visually different, notwithstanding the fact that the elephants in profile, with a single eye drawn, were represented in both the contested mark and the earlier figurative marks.

27 The applicant challenges the soundness of that conclusion as regards the comparison of the contested mark with the earlier figurative marks.

28 First, it submits that the Board of Appeal wrongly relied on differences relating to elements of the marks at issue which would not be perceived as distinctive by the relevant public.

29 In that regard, the applicant rightly argues that the rounded rectangle surrounding the representation of the elephants in the contested mark will be perceived as merely delimiting the mark in space. However, it does not follow that that element has no influence with regard to the overall visual impression created by the mark. The rectangle concerned determines the contours of the sign at issue, as evidenced by the fact that its lines ‘cut’ the representation of several elephants, which for that reason appear only partially in that sign.

30 By contrast, as the applicant points out, the relevant public will not be led by its examination to consider the precise layout of the different representations of elephants in the contested mark or the differences between an Asian elephant and an African elephant. Consequently, the facts that, first, the contested mark contains diagonal lines of elephants and, second, the elephants represented in that mark are possibly not of the same type as those represented in the earlier figurative marks are immaterial to the relevant public’s perception of the marks at issue.

31 Secondly, according to the applicant, the Board of Appeal failed to take into consideration significant similarities. Both the contested mark and the earlier figurative marks, it submits, contain a naive representation of a young elephant, of stocky build and with very short legs sketched in the form of two rectangles.

32 It should be noted, however, as the Board of Appeal found in paragraphs 22 and 24 of the contested decision, that, although both the contested mark and the earlier figurative marks contain stylised representations of an elephant seen in profile, those representations none the less differ in significant respects.

33 Whereas the figure of an elephant represented in the contested mark has a rather child‑like nature, the earlier figurative marks have an abstract and clear‑cut design, with a minimalist outline. Likewise, the contested mark is composed of white elephants with a black outline, whereas the earlier figurative marks consist of a black elephant with a white outline.

34 Third, contrary to what the applicant claims, the fact that the contested mark contains a representation of several elephants is not immaterial in the perception of the relevant public and, therefore, in the overall visual impression created by that mark. As the Board of Appeal observed in paragraph 21 of the contested decision, the contested mark, as regards its overall visual perception, is characterised by the representation of several elephants in a rectangular label with rounded corners. Consequently, the representation of multiple elephants is an inherent part of that mark.

35 In so far as the applicant relies, in that regard, on the case‑law of the German courts, it must be pointed out that the Community trade mark regime is an autonomous system with its own set of objectives and rules peculiar to it, and it applies independently of any national system. Accordingly, OHIM and, if relevant, the European Union Courts are not bound by decisions given in the Member States (see Case T‑106/00 Streamserve v OHIM (STREAMSERVE) [2002] ECR II‑723, paragraph 47 and the case‑law cited), which constitute only one factor which may be taken into consideration, without being given decisive weight, in invalidity proceedings relating to a Community trade mark (see, by analogy, Case T‑337/99 Henkel v OHIM (Red and white round tablet) [2001] ECR II‑2597, paragraph 58 and the case‑law cited).

36 However, the decisions relied on by the applicant concern the multiple repetition of a word element in a mark, whereas the element concerned in the present case is figurative. Given that the multiple repetition of those two types of element does not, as a general rule, have the same impact on the overall impression created by a mark, it must be held that the decisions of the German courts on which the applicant relies cannot be transposed to the present case and cannot therefore be taken into consideration by the Court.

37 The applicant also submits, in that respect, that it is free to reproduce the earlier figurative marks several times and in different sizes on its products. It refers, in that regard, to practices in the fashion sector and, in particular, to the ‘monogram products’ of certain luxury brands.

38 However, that argument goes beyond the comparison of the contested mark with the earlier marks, since it concerns the use of those marks. Moreover, as follows from paragraph 29 above, the contested mark does not consist of a representation of an indeterminate number of elephants, but of a defined area which includes the complete or partial representation of several elephants.

39 In any event, the applicant does not substantiate its arguments on practices in the fashion sector. Nor does it explain the relevance of the example of ‘monogram products’, given that the marks concerned in the present case do not have the appearance of monograms.

40 Since none of the applicant’s arguments relating to the representation of several elephants in the contested mark can be accepted, it must be held that that element tends to differentiate visually the contested mark from the earlier figurative marks, which contains only one representation of that animal.

41 In the light of all the foregoing, it must be held that the Board of Appeal did not err in concluding, in paragraph 24 of the contested decision, that, taken together, the contested mark and the earlier figurative marks were visually different.

Phonetic comparison

42 First of all, it should be noted that the applicant is correct in submitting that there is inconsistency in the reasoning of the contested decision with regard to phonetic similarity. Paragraph 25 of the contested decision, according to which figurative marks are not pronounced, cannot, prima facie, be reconciled with paragraph 26 of the decision, according to which, in any event, the oral description of the contested mark differs from that of the earlier marks.

43 Furthermore, contrary to what OHIM essentially submits, the argument in paragraph 26 of the contested decision does not appear to have been set out purely for the sake of completeness. In paragraph 37 of the contested decision, which deals with the global assessment of whether there was a likelihood of confusion, the Board of Appeal expressly referred to the phonetic differences which had been found to exist between the marks concerned.

44 Consequently, it must be held that the contested decision is vitiated by contradictory reasoning as regards the assessment of phonetic similarity.

45 The fact none the less remains that, contrary to what the applicant submits, a phonetic comparison is not relevant in the examination of the similarity of a figurative mark without word elements with another mark (see, to that effect, Joined Cases T‑5/08 to T‑7/08 Nestlé v OHMI — Master Beverage Industries (Golden Eagle and Golden Eagle Deluxe) [2010] ECR II‑1177, paragraph 67).

46 A figurative mark without word elements cannot, by definition, be pronounced. At the very most, its visual or conceptual content can be described orally. Such a description, however, necessarily coincides with either the visual perception or the conceptual perception of the mark in question. Consequently, it is not necessary to examine separately the phonetic perception of a figurative mark lacking word elements and to compare it with the phonetic perception of other marks.

47 In those circumstances, and given that the contested mark is a figurative mark lacking word elements, it cannot be concluded there is either a phonetic similarity or a phonetic dissimilarity between that mark and the earlier marks.

Conceptual comparison

48 In paragraph 28 of the contested decision, the Board of Appeal found, first, that the earlier word mark meant ‘elephants’ in German, the language of the territory in which it was registered. Second, according to the Board of Appeal, the figurative marks concerned referred very clearly to the concept of ‘elephant’. However, in so far as the earlier marks feature only one single elephant, whereas the contested mark includes several elephants, of different sizes, arranged in a particular way and contained within a rectangular label with rounded corners, the Board of Appeal concluded that they were conceptually similar rather than identical.

49 The applicant submits that there is a higher degree of conceptual similarity than was found by the Board of Appeal. It claims, in particular, that there is conceptual identity between the contested mark and the earlier word mark.

50 With regard, in that context, to the conceptual perception of the contested mark, it was found, in paragraph 30 above, that the fact that the contested mark featured diagonal lines of elephants was immaterial to the relevant public’s perception. Consequently, the relevant public will not perceive any particular arrangement in the series of elephants represented in the contested mark. Next, it follows from paragraph 29 above that the rectangle with rounded corners surrounding the representation of the elephants in the contested mark will be perceived as delimiting the mark in space. On that basis, no particular conceptual content will be attributed to that element. Finally, given that the average consumer must, as a general rule, place his trust in the imperfect picture of the marks that he has kept in his mind (see, to that effect, Case C‑342/97 Lloyd Schuhfabrik Meyer [1999] ECR I‑3819, paragraph 26), the conceptual perception of the contested mark will not be affected by the presence of elephants of different sizes.

51 In those circumstances, it must be held that the relevant public will perceive the contested mark as referring, on a conceptual level, simply to elephants. The applicant is therefore correct in its contention that there is conceptual identity between the contested mark and the earlier word mark.

52 With regard to the conceptual comparison between the contested mark and the earlier figurative marks, it is common ground that those earlier marks will be perceived as referring to the concept of ‘elephant’. Given the proximity between the concept of ‘elephant’ and that of ‘elephants’ it must be concluded, as the Board of Appeal did, that there is conceptual similarity between the contested mark and the earlier figurative marks.

53 In conclusion, it must be held that the contested decision is vitiated by errors in the assessment of phonetic similarity and conceptual similarity.

54 However, the impact of those errors on the correctness of the Board of Appeal’s finding that there was no likelihood of confusion and, consequently, on the soundness of the operative part of the contested decision can be assessed only at the stage of the global examination of all the relevant factors. For the purposes of that examination, it must be held that the marks concerned are visually different, that their phonetic comparison is irrelevant and that, conceptually, the contested mark is identical to the earlier word mark and similar to the earlier figurative marks.

Failure to take into consideration the enhanced distinctiveness of the earlier marks

55 In paragraph 30 of the contested decision, the Board of Appeal found that the applicant had not expressly claimed, before the Cancellation Division, that the earlier marks had acquired enhanced distinctiveness through their intensive use. The submissions and evidence put forward by the applicant before the Cancellation Division related solely to the issue of genuine use of those marks, raised by the intervener. Consequently, the Board of Appeal did not examine whether the earlier marks had acquired enhanced distinctiveness by virtue of their use. It found, in paragraph 31 of the contested decision, that they had an average degree of distinctiveness.

56 The applicant denies that it did not claim that the earlier marks had enhanced distinctiveness. It refers, in that regard, to the submissions which it put before the Cancellation Division on 11 October 2007.

57 Page 11 of those submissions, in their translation into the language of the proceedings before OHIM, as put before the Cancellation Division on 7 November 2007, includes the following passage:

‘3. Contrary to the view taken by the opponent, the [earlier marks] also do not have weak distinctive character. On the contrary: because of their intensive and lengthy use shown previously on the German market, they have above-average distinctive character.’

58 It follows from that passage that the applicant expressly relied on the enhanced distinctiveness of the earlier marks acquired through their earlier use. Therefore, both the Cancellation Division, pursuant to Article 74(1) of Regulation No 40/94, in force on the date of its decision, and the Board of Appeal, pursuant to Article 76(1) of Regulation No 207/2009, were required to examine the merits of that claim in their decisions.

59 The arguments raised by OHIM are not such as to call that finding into question.

60 Thus, first, OHIM submits that the applicant did not argue that the earlier marks had acquired enhanced distinctiveness either in the standard application form for a declaration of invalidity, submitted on 20 February 2007, or in the submissions accompanying that form.

61 However, the standard form does not contain a section dealing with the distinctiveness of the earlier marks, but only a section dealing with their possible reputation, which was not claimed in the present case.

62 Moreover, it follows from neither Regulation No 40/94 nor Regulation No 207/2009 that, in order to be admissible, the claim that the earlier mark has acquired enhanced distinctiveness must be made when the application for a declaration of invalidity is submitted.

63 Second, according to OHIM, the passage cited in paragraph 57 above is an isolated and brief assertion, submitted in response to the submissions of the intervener in the context of the discussion on the issue of proof of genuine use of the earlier marks.

64 However, while the passage in question is brief, its meaning is sufficiently clear and precise.

65 Moreover, it cannot be argued that the applicant’s claim was made in the context of the discussion on proof of genuine use of the earlier marks. That issue was dealt with in points I and II of the applicant’s submissions of 11 October 2007, whereas the passage cited in paragraph 57 above is taken from point III of that document, dealing with other arguments put forward by the intervener. As OHIM itself acknowledges, those arguments included the issue of the distinctiveness of the earlier marks.

66 Third, OHIM submits that the applicant failed to adduce specific evidence to substantiate the alleged enhanced distinctiveness of the earlier marks. Moreover, according to OHIM, the evidence set out in the annex to the applicant’s submissions of 11 October 2007 sought to prove genuine use of the earlier marks.

67 In that regard, it follows from a contextual reading of the passage cited in paragraph 57 above that the applicant referred, in order to substantiate the claim that the earlier marks had acquired enhanced distinctiveness, to all the evidence which it had put forward to prove genuine use of those marks.

68 Moreover, that evidence, namely publicity material featuring the earlier marks and formal statements relating to the volume of sales of goods bearing the marks, was relevant, prima facie, not only in regard to genuine use of the earlier marks, but also in regard to their possible distinctiveness acquired through use.

69 In those circumstances, it must be held that the applicant identified the evidence on which it relied with sufficient precision to allow OHIM to examine the merits of its claims and to allow the intervener to put forward its submissions in that regard.

70 In the light of all of the foregoing, it must be concluded that the Board of Appeal erred in finding that the applicant had not expressly claimed that the earlier marks had acquired enhanced distinctiveness through their use. The Board of Appeal therefore also erred in not examining the merits of the applicant’s claims on that point.

71 That error means that the Board of Appeal failed to examine a potentially relevant factor in the global assessment of whether there was a likelihood of confusion between the contested mark and the earlier marks (see, to that effect, Case C‑251/95 SABEL [1997] ECR I‑6191, paragraph 24; Case C‑39/97 Canon [1998] ECR I‑5507, paragraph 18; and Lloyd Schuhfabrik Meyer, paragraph 20).

72 In those circumstances, the Court does not have all the elements necessary to determine the soundness of the global assessment as to whether there was a likelihood of confusion, as carried out by the Board of Appeal in the contested decision.

73 Consequently, the single plea must be upheld and the contested decision consequently annulled, without there being any need to examine the arguments relating to that assessment, in particular so far as concerns the relationship between the different elements derived from the comparison of the signs at issue.

Costs

74 Under Article 87(2) of the Rules of Procedure of the General Court, the unsuccessful party is to be ordered to pay the costs if they have been applied for in the successful party’s pleadings.

75 In the present case, OHIM and the intervener have been unsuccessful. Consequently, OHIM must be ordered to bear its own costs and also to pay the costs of the applicant, in accordance with the form of order sought by the latter.

76 The intervener must be ordered to bear its own costs.

On those grounds,

THE GENERAL COURT (Fourth Chamber)

hereby:

1. Annuls the decision of the Fourth Board of Appeal of the Office for Harmonisation in the Internal Market (Trade Marks and Designs) (OHIM) of 15 July 2010 (Case R 1638/2008-4);

2. Orders OHIM to bear its own costs and to pay the costs of Dosenbach-Ochsner AG Schuhe und Sport;

3. Orders Sisma SpA to bear its own costs.

Pelikánová | Jürimäe | Van der Woude |

Delivered in open court in Luxembourg on 7 February 2012.

[Signatures]