JUDGMENT OF THE GENERAL COURT (First Chamber)

28 September 2010 (*)

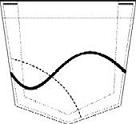

(Community trade mark – Application for Community figurative mark representing two curves on a pocket – Absolute ground for refusal – Lack of distinctive character – Article 7(1)(b) of Regulation (EC) No 207/2009 )

In Case T‑388/09,

Rosenruist – Gestão e serviços, Lda, established in Funchal (Portugal), represented by S. Rizzo and S. González Malabia, lawyers,

applicant,

v

Office for Harmonisation in the Internal Market (Trade Marks and Designs) (OHIM), represented by A. Folliard-Monguiral, acting as Agent,

defendant,

ACTION brought against the decision of the Second Board of Appeal of OHIM of 18 June 2009 (Case R 237/2009-2) concerning an application for registration as a Community trade mark of a figurative sign representing two curves on a pocket,

THE GENERAL COURT (First Chamber),

composed of I. Wiszniewska-Białecka (Rapporteur), President, F. Dehousse and H. Kanninen, Judges,

Registrar: E. Coulon,

having regard to the application lodged at the Court Registry on 2 October 2009,

having regard to the response lodged at the Court Registry on 15 December 2009,

having regard to the fact that no application for a hearing was submitted by the parties within the period of one month from notification of closure of the written procedure, and having therefore decided, acting upon a report of the Judge-Rapporteur, to rule on the action without an oral procedure pursuant to Article 135a of the Rules of Procedure of the Court,

gives the following

Judgment

Background to the dispute

1 On 9 May 2008 the applicant, Rosenruist – Gestão e serviços, Lda, filed an application for registration of a Community trade mark with the Office for Harmonisation in the Internal Market (Trade Marks and Designs) (OHIM) pursuant to Council Regulation (EC) No 40/94 of 20 December 1993 on the Community trade mark (OJ 1994 L 11, p. 1), as amended (replaced by Council Regulation (EC) No 207/2009 of 26 February 2009 on the Community trade mark (OJ 2009 L 78, p. 1)).

2 The trade mark in respect of which registration was sought is the figurative sign reproduced below:

3 The description of the mark given in the application for registration reads: ‘Two Curves Crossed in One Point Design inserted in a Pocket; the mark consists of a decorative stitching made of Two Curves Crossed in One Point Design Inserted in a Pocket; one of the curves is characterised by an arched form, dr[a]wn with a fine stroke, while the second one is characterised by a sinusoidal form, dr[a]wn with a thick stroke; the unevenly broken lines represent the perimeter of the pocket to which applicant makes no claim and which serves only to indicate the position of the mark on the pocket’.

4 The goods for which registration was sought are in Classes 18 and 25 of the Nice Agreement Concerning the International Classification of Goods and Services for the Purposes of the Registration of Marks of 15 June 1957, as revised and amended, and correspond, for each of those classes, to the following description:

– Class 18: ‘Bags, pouches, purses, wallets, valises, trunks, make-up bags and empty vanity cases, document holders, umbrellas, handbags’;

– Class 25: ‘Dresses, skirts, trousers, shirts, jackets, overcoats, raincoats, coats and pullovers, jerkins, hats, scarves, foulards, hosiery (clothing), neckerchieves, gloves (clothing), belts for clothing, shoes, boots, sandals, clogs, slippers’.

5 By decision of 17 December 2008, the examiner refused registration for all the goods on the ground that the mark in question was devoid of any distinctive character within the meaning of Article 7(1)(b) of Regulation No 40/94 (now Article 7(1)(b) of Regulation No 207/2009).

6 On 13 February 2009 the applicant filed a notice of appeal before OHIM against that decision, pursuant to Articles 57 to 62 of Regulation No 40/94 (now Articles 58 to 64 of Regulation No 207/2009).

7 By decision of 18 June 2009 (‘the contested decision’), the Second Board of Appeal of OHIM dismissed the appeal. The Board of Appeal held that, since the goods in question were goods which either covered or protected the human body or which were fashion accessory or travel goods that met basic fashion needs, the relevant public was composed of average consumers in the European Union who were reasonably well informed and reasonably observant and circumspect. Taking into account the description of the trade mark applied for, the Board of Appeal considered that that mark was a ‘position mark’ consisting of a stitched pattern that had a specific position on a pocket. It considered the stitched pattern to be a mere variation of a common feature of goods covered by the mark in question that would not enable the average consumer to recognise the origin of those goods. It concluded that the trade mark applied for was devoid of any distinctive character within the meaning of Article 7(1)(b) of Regulation No 207/2009.

Forms of order sought

8 The applicant claims the Court should:

– annul the contested decision and direct OHIM to register the mark in question for all the goods designated;

– order OHIM to pay the costs.

9 OHIM contends that the Court should:

– dismiss the application;

– order the applicant to pay the costs.

Law

10 In support of its action, the applicant submits a single plea in law alleging infringement of Article 7(1)(b) of Regulation No 207/2009. The applicant, unlike the Board of Appeal, considers that the sign in question will not be perceived by the relevant public as an exclusively decorative element or a mere variation of a common feature of the goods in question, but as an original sign which has the minimum degree of distinctive character sufficient to function as a trade mark.

11 OHIM disputes the applicant’s arguments.

12 According to Article 7(1)(b) of Regulation No 207/2009, trade marks which are devoid of any distinctive character are not to be registered. According to settled case-law, the marks referred to in Article 7(1)(b) of Regulation No 207/2009 are those which are regarded as incapable of performing the essential function of a trade mark, namely that of identifying the commercial origin of the goods or services at issue, thus enabling the consumer who acquired the goods or services covered by the mark to repeat the experience if it proves to be positive, or to avoid it if it proves to be negative, on the occasion of a subsequent acquisition (Case T‑34/00 Eurocool Logistik v OHIM (EUROCOOL) [2002] ECR II-683, paragraph 37, and Case T‑139/08 The Smiley Company v OHIM (Representation of half a smiley smile) [2009] ECR II‑0000, paragraph 14).

13 The distinctive character of a mark must be assessed, first, by reference to the goods or services in respect of which registration or the protection of the mark has been applied for and, second, by reference to the perception of the relevant public, which consists of average consumers of those goods or services (Joined Cases C‑456/01 P and C‑457/01 P Henkel v OHIM [2004] ECR I‑5089, paragraph 35, and Representation of half a smiley smile, paragraph 12 above, paragraph 15).

14 A minimum degree of distinctive character is, however, sufficient to render the absolute ground for refusal set out in Article 7(1)(b) of Regulation No 207/2009 inapplicable (Case T-337/99 Henkel v OHIM (Round red and white tablet) [2001] ECR II-2597, paragraph 44, and Representation of half a smiley smile, paragraph 12 above, paragraph 16).

15 In the present case, the applicant does not dispute the assessment of the Board of Appeal according to which, since the goods in question are goods in Classes 18 and 25 which either cover or protect the human body or which are fashion accessory or travel goods that meet basic fashion needs, the relevant public is composed of average consumers throughout the European Union who are reasonably well informed and reasonably observant and circumspect.

16 By contrast, the applicant disputes the Board of Appeal’s assessment regarding the distinctive character of the mark in question.

17 It is apparent from the description of the mark in question given in paragraph 3 above that it consists of two crossed curves which are stitched (topstitched) on a pocket in a precise position. The Board of Appeal therefore rightly considered, without being contradicted by the applicant, that the mark in question was a ‘position mark’ consisting of a stitched pattern that had a specific position on a pocket.

18 The Board of Appeal took the view that a stitched pocket was a usual and commonplace feature of many fashion goods, in particular those in Classes 18 and 25. The average consumer would perceive the stitching merely to be decorative features rather than an indication of the origin of the goods. The Board of Appeal stated that the stitched pattern covered by the application for registration was a mere variation of a common feature found on pockets of clothing and on the other fashion goods covered by the trade mark in question. It added that even if it were correct that it was unusual to see a pocket on some of the goods in question, the consumer would pay scant attention to the stitched pattern on the pocket when purchasing such goods. The Board of Appeal considered that the mark in question would not trigger a ‘visual stimulus’ enabling the average consumer to recognise the origin of those goods ‘unless he or she [had] been previously educated to do so through intensive use’.

19 That analysis by the Board of Appeal must be endorsed. It should be noted that in the fashion sector patterns stitched on pockets are commonplace. Topstitched lines are typical decoration for pockets in general and in particular for pockets of clothing in Class 25. Furthermore, a number of fashion goods in Class 18 also usually have pockets with decorative stitching. Consumers are therefore used to seeing patterns stitched on pockets of clothing or fashion goods. They will therefore perceive them as a decorative element and not as an indication of the commercial origin of those goods.

20 Since the mark in question represents two crossed curves stitched on a pocket, one of which is a fine, arched form while the other is a thicker, sinusoid form, it constitutes a simple pattern, as the applicant accepts. The mark does not contain any element that is eye-catching and will attract the attention of consumers. As OHIM states, the description of the mark in question specifically refers to ‘decorative stitching’.

21 Since the applicant itself gives a number of examples of stitched patterns on pockets that may be described as curved lines that cross each other, it must be concluded that the mark in question does not have any unique, original or unusual character.

22 It is true that it could be maintained that whether or not a mark may serve a decorative or ornamental purpose is irrelevant for the purposes of assessing its distinctive character. A sign which fulfils functions other than that of a trade mark in the traditional sense of the term is only distinctive for the purposes of Article 7(1)(b) of Regulation No 207/209, however, if it may be perceived immediately as an indication of the commercial origin of the goods or services in question, so as to enable the relevant public to distinguish, without any possibility of confusion, the goods or services of the owner of the mark from those of a different commercial origin (see Representation of half a smiley smile, paragraph 12 above, paragraph 30, and case-law cited).

23 Moreover, a finding that a mark has distinctive character within the meaning of Article 7(1)(b) of Regulation No 207/2009 is not subject to a finding of a specific level of creativity on the part of the applicant for the trade mark. None the less the trade mark should enable the relevant public to identify the origin of the goods or services it covers and to distinguish them from those of other undertakings (Case C-329/02 P SAT.1 v OHIM [2004] ECR I-8317, paragraph 41, and Representation of half a smiley smile, paragraph 12 above, paragraph 27).

24 It is always necessary therefore for the sign in question, even if it may serve a decorative purpose and need not meet a specific level of creativity, to have a minimum degree of distinctive character.

25 In order to have the minimum degree of distinctiveness required under Article 7(1)(b) of Regulation No 207/2009, the mark concerned must simply appear prima facie capable of enabling the relevant public to identify the origin of the goods or services covered by the Community trade mark application and to distinguish them, without any possibility of confusion, from those of a different origin (Case T‑441/05 IVGImmobilien v OHIM (I) [2007] ECR II‑1937, paragraph 55).

26 That is not, however, the position in the present case. The mark in question does not have any characteristic element, nor any memorable or eye-catching features likely to confer a minimum degree of distinctive character and enabling the consumer to perceive it otherwise than as a typical decoration of a pocket for goods in Classes 18 and 25. As OHIM points out, it does not depart significantly from the standard presentation of pockets and will therefore be perceived simply as decoration. The Board of Appeal was therefore right to consider that the mark in question constituted a mere variation of topstitching commonly found on pockets of clothing and other fashion goods covered by the trade mark in question.

27 The mark in question must accordingly be considered to be a simple, commonplace pattern with an exclusively decorative function, which has no aspect that would enable the relevant public to identify the commercial origin of the goods described in the trade mark application or to distinguish them from others with a different origin.

28 That conclusion is not affected by the arguments put forward by the applicant.

29 First, as regards the applicant’s argument that the Board of Appeal did not examine whether the mark in question had a minimum degree of distinctive character in relation to each of the relevant goods, it should be noted that where the same ground of refusal is given for a category or group of goods or services, the competent authority may confine itself to general reasoning for all of the goods or services concerned (judgment of 15 October 2008 in Case T‑297/07 TridonicAtco v OHIM (Intelligent Voltage Guard), not published in the ECR, paragraph 22). In the present case, the goods in question are clothing in Class 25 and fashion goods in Class 18. Although the contested decision does not contain a differentiated assessment for each of the goods in question, nevertheless the Board of Appeal conducted an analysis of the relevant public’s perception of the mark applied for, on the one hand, in respect of the relevant category of clothing and, on the other hand, in respect of the relevant category of fashion goods. It considered that the relevant public would perceive the mark in question in the same way on all the clothing and all the fashion goods concerned. The Board of Appeal therefore provided general reasoning for both the categories of goods in question when assessing the distinctive character of the mark and the applicant’s argument in that regard cannot be accepted.

30 Second, it is necessary to reject the applicant’s argument that the mark in question has a specific appearance and cannot be considered to be altogether banal, since the sign in question is entirely arbitrary and, although simple, it is elegant and eye-catching and hence capable of attracting the attention of consumers and impressing itself on their consciousness; it sufficiently diverges from any common symmetrical lines or geometric pattern and conveys the idea of movement. In fact, such elements only make a mark distinctive in so far as it is immediately perceived by the relevant public as an indication of the commercial origin of the applicant’s goods, thus enabling the relevant public to distinguish, without any possibility of confusion, the applicant’s goods from those of a different commercial origin (see, to that effect, Case T 320/03 Citicorp v OHIM (LIVE RICHLY) [2005] ECRII‑3411, paragraph 84). The fact that the mark in question may be perceived as elegant or may convey the idea of movement, and hence be memorable, nevertheless does not mean that it is distinctive.

31 Equally unconvincing is, third, the applicant’s argument that the relevant public would not perceive a stitched pattern on a pocket as mere decoration, since, in the fashion sector, it is accustomed to distinguishing the origin of different goods not only by word marks but also by ‘position marks’ and it is particularly sensitive to graphical signs and stylised elements, such as stitch devices, which are frequently used as trade marks in the fashion world.

32 Assessment of the distinctive character of the mark in question consists in ascertaining whether it is, per se, capable of being perceived, by the relevant public as an indication which makes it possible for it to identify the commercial origin of the goods in question without any possibility of confusion with those of a different origin. Accordingly, the mere fact that other marks, although equally simple, have been regarded as being so capable and, therefore, as not being devoid of any distinctive character, is not conclusive for the purpose of establishing whether the mark at issue also has the minimum degree of distinctive character necessary for registration (see to that effect, Representation of half a smiley smile, paragraph 12 above, paragraph 34).

33 Moreover, the argument that the consumer is used to recognising stitch devices as an indication of the commercial origin of goods is also irrelevant, since the fact that such signs are recognised as marks by consumers does not necessarily mean that they have intrinsic distinctive character. It is in fact possible for a mark to acquire distinctive character through use over time.

34 Fourth, as regards the applicant’s argument that the fact that there are on the market simple and stylised logos on the pockets of clothing is not an obstacle to registration of this kind of mark, it should be noted that the Board of Appeal considered the stitched pattern covered by the application for registration to be a mere variation of a common feature found on pockets of clothing and on other fashion goods covered by the trade mark in question. Contrary to what the applicant maintains, the Board of Appeal did not consider that the mere fact that there are on the market stitched patterns on the pockets of clothing constitutes an obstacle to registration of the mark in question. The Board of Appeal found that, since the mark in question had no originality as compared with stitching usually present on the goods in question, that mark would not particularly catch the attention of consumers, who would perceive it as mere decoration. The Board of Appeal did not therefore refrain from examining whether the mark in question possessed a minimum degree of distinctive character.

35 It follows that the applicant is wrong in maintaining that the Board of Appeal did not analyse why the mark in question was devoid of any distinctive character and, without any real assessment of the actual circumstances of the case, merely made general assumptions. It is thus necessary to reject also the applicant’s argument that the contested decision does not refer to the mark in question, but more generally to the lack of distinctive character of any kind of ‘stitching signs’.

36 Fifth, it is necessary to reject the applicant’s argument that the Board of Appeal, in stating that the mark in question would not trigger a ‘visual stimulus’ enabling the average consumer to recognise the origin of the goods in question ‘unless he or she has been previously educated to do so through intensive use’, applied more stringent criteria for assessing distinctive character to figurative marks than to other marks. That argument stems in fact from a misreading of the contested decision, since the Board of Appeal did not infer that the mark in question lacked distinctive character from lack of use. It is apparent from the contested decision that, having examined the mark in question, the Board of Appeal found that that mark had no intrinsic distinctive character. It then stated that the mark in question would not therefore enable the average consumer to recognise the origin of those goods unless it could be shown that the existence of distinctive character had been acquired through use.

37 Sixth, as regards the argument that the burden of proof with respect to lack of distinctiveness was borne by OHIM, which did not produce a single example of use of the sign in question or of a similar sign on the marketplace, on the one hand, it must be pointed out that if an applicant claims that a trade mark applied for is distinctive, despite OHIM’s analysis, it is for that applicant to provide specific and substantiated information to show that the trade mark applied for has an intrinsic distinctive character (Case C‑238/06 P Develey v OHIM [2007] ECR I‑9375, paragraph 50). On the other hand, although the fact that a mark is capable of being commonly used in trade for the presentation of the goods or services in question is a relevant criterion in relation to Article 7(1)(c) of Regulation No 207/2009, that criterion is not the yardstick by which Article 7(1)(b) of that regulation must be applied (see Case T‑471/07 Wella v OHIM (TAME IT) [2009] ECR I‑0000, paragraph 34, and case-law cited). It follows that, in order to find that the mark in question was devoid of any distinctive character within the meaning of Article 7(1)(b) of Regulation No 207/2009, the Board of Appeal did not in any event have to refer to such examples.

38 Seventh, it is necessary to reject the applicant’s argument that the fact that in its previous decision-making practice OHIM has allowed registration of Community trade marks which consist of quite simple signs on a pocket that are similar to the mark in question, on the one hand, shows that that type of mark has been recognised as having intrinsic distinctive character and, on the other hand, makes it impossible to define what standards OHIM applies in assessing whether or not a trade mark is distinctive.

39 According to settled case-law, the minimum degree of distinctiveness required for the purposes of registration or protection in the European Union must be assessed in the light of the circumstances of each case. Decisions concerning registration or the protection of a sign as a Community trade mark which the Boards of Appeal are called on to take under Regulation No 207/2009 are adopted in the exercise of circumscribed powers. Accordingly, the legality of the decisions of Boards of Appeal must be assessed solely on the basis of that regulation, as interpreted by the European Union judicature, and not on the basis of a previous decision-making practice of those boards (Case C-37/03 P BioID v OHIM [2005] ECR I‑7975, paragraph 47, and Representation of half a smiley smile, paragraph 12 above, paragraph 36). Consequently, the fact that simple signs on a pocket have been registered by OHIM as Community trade marks is not relevant for the purposes of assessing whether or not the mark in question is devoid of any distinctive character within the meaning of Article 7(1)(b) of Regulation No 207/2009.

40 Lastly, the applicant’s argument that OHIM should have taken into account, in the procedure for registration of the mark in question, the fact that a large number of national authorities have taken a position in favour of the distinctive character of that mark must be rejected as inadmissible. The same applies with regard to the evidence produced in support of that argument, namely national registrations for a figurative sign composed of two curves and constituting part of the mark in question.

41 According to settled case-law, the Community trade mark regime is an autonomous system which applies independently of any national system. Accordingly, whether or not a sign is registrable as a Community trade mark must be assessed by reference to the relevant European Union legislation only, with the result that neither OHIM nor, as the case may be, the European Union Court is bound by decisions in other Member States finding the same sign to be registrable as a trade mark (Case T‑36/01 Glaverbel v OHIM (Glass-sheet surface) [2002] ECR II‑3887, paragraph 34; orders of 28 April 2009 in Case T‑283/07 Tailor v OHIM(Representation of a right pocket), not published in the ECR, paragraph 24, and Case T‑282/07 Tailor v OHIM (Representation of a left pocket), not published in the ECR, paragraph 24).

42 It follows from all the above that the Board of Appeal was correct in holding that the mark in question was devoid of a minimum degree of distinctive character and that it could not be registered to designate the goods in question, pursuant to Article 7(1)(b) of Regulation No 207/2009.

43 Accordingly, the single plea in law, alleging infringement of Article 7(1)(b) of Regulation No 207/2009, must be dismissed as unfounded, as must the action in its entirety.

Costs

44 Under Article 87(2) of the Rules of Procedure of the Court, the unsuccessful party is to be ordered to pay the costs if they have been applied for in the successful party’s pleadings. Since the applicant has been unsuccessful, it must be ordered to pay the costs, in accordance with the forms of order sought by OHIM.

On those grounds,

THE GENERAL COURT (First Chamber)

hereby:

1. Dismisses the action;

2. Orders Rosenruist – Gestão e serviços, Lda to pay the costs.

Wiszniewska-Białecka | Dehousse | Kanninen |

Delivered in open court in Luxembourg on 28 September 2010.

[Signatures]