JUDGMENT OF THE COURT OF FIRST INSTANCE (Fourth Chamber)

23 May 2007 (*)

(Community trade mark – Applications for three-dimensional trade marks – Square white tablets with coloured floral design – Absolute ground for refusal – Article 7(1)(b) of Regulation (EC) No 40/94 – Absence of distinctive character)

In Joined Cases T‑241/05, T‑262/05 to T‑264/05, T‑346/05, T‑347/05, T‑29/06 to T‑31/06,

The Procter & Gamble Company, established in Cincinnati, Ohio (United States), represented by G. Kuipers, lawyer,

applicant,

v

Office for Harmonisation in the Internal Market (Trade Marks and Designs) (OHIM), represented initially by D. Schennen, and subsequently by G. Schneider, acting as Agents,

defendant,

NINE ACTIONS brought against the decisions of the First Board of Appeal of OHIM of 14 April 2005 (Case R 843/2004-1), of 3 May 2005 (Case R 845/2004-1), of 4 May 2005 (Case R 849/2004-1), of 1 June 2005 (Case R 1184/2004-1), of 6 July 2005 (Cases R 1188/2004-1 and R 1182/2004-1), of 16 November 2005 (Case R 1183/2004-1), of 21 November 2005 (Case R 1072/2004-1) and of 22 November 2005 (Case R 1071/2004-1), concerning applications to register three-dimensional trade marks,

THE COURT OF FIRST INSTANCE OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES (Fourth Chamber),

composed of H. Legal, President, V. Vadapalas and N. Wahl, Judges,

Registrar: C. Kantza, Administrator,

having regard to the applications lodged at the Registry of the Court of First Instance on 29 June 2005 (Case T‑241/05), 18 July 2005 (Cases T‑262/05 to T‑264/05), 12 September 2005 (Cases T‑346/05 and T‑347/05) and 24 January 2006 (Cases T‑29/06 to T‑31/06),

having regard to the responses lodged at the Registry of the Court of First Instance on 30 September 2005 (Cases T‑241/05 and T‑262/05 to T‑264/05), 26 October 2005 (Cases T‑346/05 and T‑347/05) and 18 May 2006 (Cases T‑29/06 to T‑31/06),

having regard to the joinder of the cases decided on 24 October 2006,

further to the hearing on 13 December 2006,

gives the following

Judgment

Background to the dispute

1 On 31 May 2000, the applicant submitted nine applications for Community trade marks to the Office for Harmonisation in the Internal Market (Trade Marks and Designs) (OHIM) under Council Regulation (EC) No 40/94 of 20 December 1993 on the Community trade mark (OJ 1994 L 11, p. 1), as amended.

2 The marks for which registration was sought, as set out below, are three-dimensional shapes:

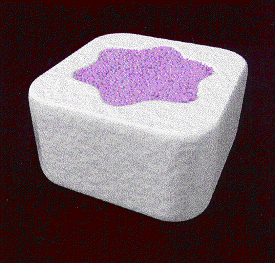

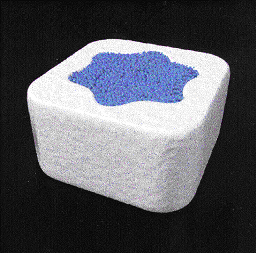

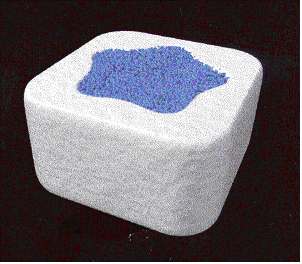

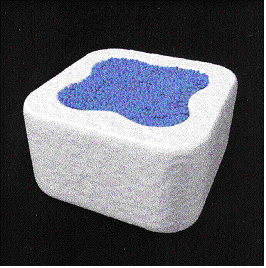

– square white tablet with a lilac six-petalled floral design (Case T‑241/05):

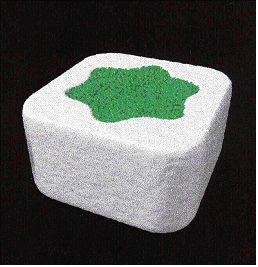

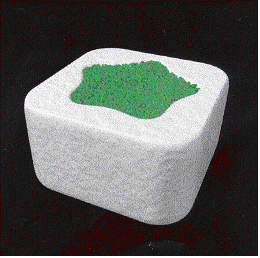

– square white tablet with a green six-petalled floral design (Case T‑262/05):

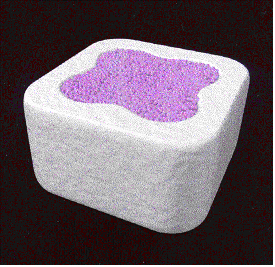

– square white tablet with a lilac four-petalled floral design (Case T‑263/05):

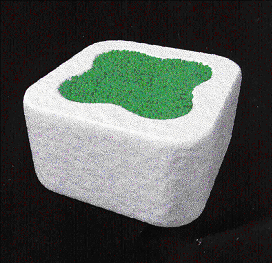

– square white tablet with a green four-petalled floral design (Case T‑264/05):

– square white tablet with a blue six-petalled floral design (Case T‑346/05):

– square white tablet with a green five-petalled floral design (Case T‑347/05):

– square white tablet with a blue five-petalled floral design (Case T‑29/06):

– square white tablet with a blue four-petalled floral design (Case T‑30/06):

– square white tablet with a lilac five-petalled floral design (Case T‑31/06):

.

.

3 The goods for which registration is sought come within Class 3 of the Nice Agreement Concerning the International Classification of Goods and Services for the Purposes of the Registration of Marks of 15 June 1957, as revised and amended, and correspond to the following description for all of the applications: ‘Washing and bleaching preparations and other substances for laundry use; cleaning, polishing, scouring and abrasive preparations; preparations for the washing, cleaning and care of dishes; soaps’.

4 By nine decisions taken between 28 July and 8 November 2004, the OHIM examiner dismissed the applications for registration pursuant to Article 7(1)(b) of Regulation No 40/94.

5 The applicant filed nine notices of appeal with OHIM against those decisions, pursuant to Articles 57 to 62 of Regulation No 40/94.

6 By nine decisions of 14 April 2005 (Case T-241/05), 3 May 2005 (Case T-263/05), 4 May 2005 (Case T-264/05), 1 June 2005 (Case T-262/05), 6 July 2005 (Cases T-346/05 and T-347/05), 16 November 2005 (Case T-31/06), 21 November 2005 (Case T-30/06) and 22 November 2005 (Case T-29/06) (together, ‘the decision contested’), the First Board of Appeal of OHIM dismissed those appeals, taking the view that the marks applied for were devoid of any distinctive character within the meaning of Article 7(1)(b) of Regulation No 40/94.

Forms of order sought by the parties

7 The applicant claims that the Court should:

– annul the contested decision;

– order OHIM to pay the costs.

8 OHIM contends that the Court should:

– dismiss the applications;

– order the applicant to pay the costs.

Law

Arguments of the parties

9 In each case, the applicant raises a single plea relating to the infringement of Article 7(1)(b) of Regulation No 40/94.

10 As regards the relevant consuming public, the applicant claims that the goods in question are aimed at consumers doing their daily shopping and who are therefore more circumspect. In addition, the tablets are amongst the most expensive goods in the category of detergent products sold in supermarkets, with the result that a high level of attention is given to their shape and design by the consumer.

11 In addition, manufacturers on the market concerned, which is highly competitive, have considerable incentive to distinguish the appearance of their goods in relation to those of their competitors in order to attract consumers’ attention, as demonstrated by the large number of applications for the registration of shapes of detergent tablets as marks. The examples of television advertising, annexed to the applications in Cases T-29/06 to T-31/06, confirm the argument that the tablets are used by manufacturers for purposes of distinguishing their goods. Those arguments show that consumers are fully capable of perceiving the tablet as an indication of commercial origin. This point is confirmed by the wide range of detergent tablets available on the market.

12 In the context of assessing the habits of the consumer concerned, the Board of Appeal was wrong to take account of the fact that the goods concerned are generally sold in packaging bearing a number of verbal or figurative features. The circumstances relating to the envisaged use of the marks applied for cannot have any bearing on the assessment of distinctiveness (Case T-355/00 DaimlerChrysler v OHIM (TELE AID) [2002] ECR II-1939, paragraph 42). By way of example, if the tablets are sold in packaging, they may none the less be depicted on the packaging, sold in transparent packaging or in packaging having the same shape as the mark applied for. A model of the tablet could be attached to the packaging of the product.

13 In addition, even if the Board of Appeal could have taken into account the circumstances of the contemplated use of the marks applied for, it should also have had regard to other factors, such as the price of the product, which is higher than that of washing liquid or powder, and the way in which the tablet is presented in advertising.

14 So far as concerns the marks applied for, the Board of Appeal failed to take into account all their specific features, namely:

– the thick rectangular, almost cube-like, shape of the tablet, containing two square sides with rounded edges;

– the presence of two very distinct colours, white and, depending on the tablet, lilac, green or blue;

– the layout of the colours, one of those colours being used in a design in the centre of the tablet, and not in different layers;

– the shape of design on the tablet.

15 By those elements, the marks applied for can be distinguished clearly from the detergent tablets available on the market. In support of that argument, the applicant produced representations of tablets marketed at the time when the applications for the marks in question were lodged.

16 The Board of Appeal was wrong to take the view that those elements were common for the goods claimed, dictated by practical considerations, and that they did not change significantly the appearance of the tablets. In particular, it failed to appreciate the fact that the specific feature of the tablet is its cubic form, distinguished from flatter rectangular shapes of tablet on the market, as well as its two separate colours, laid out in a unique way to attract attention. It failed to demonstrate the existence, on the date of the applications for the marks, of a tablet having comparable elements.

17 In addition to those features, the marks applied for comprise a design at the centre of the tablet which constitutes an additional and distinctive feature within the meaning of the judgments of the Court in Case T-128/00 Procter & Gamble v OHIM (Square tablet with inlay) [2001] ECR II-2785, paragraph 60, and Case T-129/00 Procter & Gamble v OHIM (Rectangular tablet with inlay) [2001] ECR II-2793, paragraph 60. In the light of that feature, the marks applied for cannot be regarded as consisting exclusively of the shape and colours of the product in question, in the absence of any graphic element.

18 The designs in question represent a floral pattern, or star with four, five or six petals. There is no tablet on the market comprising a design of a distinct form or shape. The Board of Appeal distorted that element by considering it to be comparable to a basic geometric form, such as the rectangular inlay and the triangular inlay examined in the Square tablet with inlay and Rectangular tablet with inlay judgments.

19 In addition, by taking the view that the marks presented for registration did not comprise ‘a special, extraordinary or unusual design’, the Board of Appeal required far more distinctive character than the minimum degree of distinctiveness required for the registration of a trade mark.

20 The marks applied for could have been considered distinctive on the basis of those designs alone, which are comparable to a logo or a sign. In that regard the applicant relies on the registration by OHIM of figurative marks consisting of a floral image (No 692897) and even simple geometric forms (Nos 2359776, 1868165, 3422631 and 1648120).

21 Moreover, the six-petalled design resembles the applicant’s ARIEL logo, which is registered as a Community trade mark (No 814780). The four-petalled design is comparable to another Community figurative mark belonging to the applicant (No 715904).

22 The Board of Appeal also failed to take into account the impression of each of the marks applied for as a whole, by describing it as the combination of two basic geometric shapes. No tablet on the market has the same combination of shape, colours and layout as those presented for registration; they also comprise a design.

23 The applicant notes that OHIM has registered signs comprising a rectangular tablet with an s-shaped design (No 1860170) and two round tablets containing, respectively, a ‘yin-yang’ design (No 1207455) and a figure resembling a drop of water (No 1207869).

24 It also cites the registration of a number of relevant marks by the Benelux Trade Marks Office.

25 Finally, the applicant criticises the fact that account was taken of the requirement of keeping basic geometric forms available, contained in seven contested decisions. It maintains that the same consideration is at the root of the reasoning of two decisions which do not expressly refer to it, namely the decisions contested in Cases T-346/05 and T-347/05. The consideration in question is incorrect in the present case in the light of the large number of possible combinations of tablet shapes, colours and designs. In addition, it is not relevant in the assessment of a sign’s distinctive character (Case C-329/02 P SAT.1 v OHIM [2004] ECR I-8317, paragraph 36).

26 OHIM contends that the contested decisions are a correct application of Community case-law in this area.

27 As regards the relevant public, the Board of Appeal correctly considered that it is the average consumer. That consumer makes his choice on the basis of the producer, then on the type of preparation, but has no reason to carry out a thorough examination of the tablet.

28 In order to ascertain how the washing tablets will be perceived by that average consumer, the signs in question must be assessed also in the light of the normal marketing practices for those products, such as the fact that they are sold in packaging. The possibility of selling the tablets in packaging in the same shape as the marks applied for or of using the tablet as a badge attached to the packaging is irrelevant, since such a representation will be perceived by the average consumer as no more than describing or displaying the goods contained in the packaging. The marks applied for cannot therefore be confused with a three-dimensional trade mark which is unrelated to the product concerned.

29 With regard to the assessment of the marks applied for, the applicant does not dispute the fact that they represent the goods concerned, namely washing preparations pressed into tablet form. In those circumstances, without additional elements individualising the tablets in question, the average consumer would perceive them as a possible and usual form of the goods themselves rather than as an indication of their commercial origin.

30 In the present cases, the tablets in question display just another combination of various elements already found to be non-distinctive, namely the rectangular shape with bevelled edges, the existence of various layers in different colours and the existence of inlays (Case T-336/99 Henkel v OHIM (Rectangular green and white tablet) [2001] ECR II-2589, and Rectangular tablet with inlay).

31 The shape of the tablets at issue, rectangular or cube-like, is a basic shape which is obvious for washing tablets and is usual on the market. The geometric relationship of the various edges of the cube and the bevelling are simply irrelevant variations of that shape.

32 The use of different colours, indicating to the consumer the presence of different active ingredients, fulfils a functional purpose. Moreover, in the present cases, the colours are basic colours such as green, blue and lilac.

33 The addition of an inlay in the middle of the tablet is an obvious combination of different active ingredients. The main function of the inlay is to indicate the presence of another active ingredient. It follows from the case-law that using a triangular shape for such an inlay does not confer distinctiveness on the mark (Rectangular tablet with inlay, paragraphs 59 and 60). The four, five or six petals of the inlays in question constitute a geometric shape as basic as a triangular shape.

34 Even if the shape at issue is to be interpreted as a floral design, which would require careful attention on the part of the consumer, it would only be perceived as something decorative. Furthermore, in relation to cleaning preparations, a floral shape evokes freshness, cleanliness and a pleasant smell. It is therefore an immaterial variation of an inlay in a washing tablet, rather than a distinctive design.

35 The existence of figurative Community trade marks with a shape such as that of the inlay at issue does not affect that finding. The relevant public will not perceive in the same way figurative marks independent of the shape of the goods concerned, as put forward by the applicant, and the elements of three-dimensional marks consisting of the appearance of the goods, as referred to in the present cases.

36 The elements of the marks applied for, considered alone or in combination, are not so striking and distinct that they would be perceived as something other than just another combination of basic and banal colours and shapes, that is, as just another washing tablet.

37 The earlier decisions of OHIM concerning other tablets cannot reasonably be relied on by the applicant (Case T-106/00 Streamserve v OHIM (STREAMSERVE) [2002] ECR II-723, paragraph 67). Moreover, by allowing the registration of tablets with the stylised letter ‘s’ and the ‘yin-yang’ design, OHIM took the view that those elements would not be perceived as functional elements representing a different active ingredient.

38 The fact that the marks in question were registered in Benelux cannot bind OHIM. Moreover, those registrations were obtained before the first judgments of the Court of First Instance on washing tablets were delivered.

39 In respect, finally, of the submissions relating to the requirement of availability, the Board of Appeal applied the case-law of the Court of Justice concerning colours to basic geometric shapes (Case C-104/01 Libertel [2003] ECR I-3793). Furthermore, since those submissions were used only as additional arguments, their alleged irrelevance cannot result in the annulment of the contested decisions.

Findings of the Court

40 Under Article 7(1)(b) of Regulation No 40/94 ‘trade marks which are devoid of any distinctive character’ may not be registered.

41 For a trade mark to possess distinctive character within the meaning of that article, it must serve to identify the product in respect of which registration is applied for as originating from a particular undertaking, and thus to distinguish that product from those of other undertakings. That distinctive character must be assessed, first, by reference to the products or services in respect of which registration has been applied for and, second, by reference to the perception of the relevant public (see Joined Cases C-473/01 P and C-474/01 P Procter & Gamble v OHIM [2004] ECR I-5173, paragraphs 32 and 33, and the case-law cited).

42 In the present cases, it should be pointed out that each trade mark applied for comprises the shape, colours and design of the product for which registration of the mark is sought, namely, a square white washing tablet with a colour design in the middle of the upper face.

43 According to established case-law, the criteria for assessing the distinctive character of three-dimensional trade marks consisting of the appearance of the product itself are no different from those applicable to other categories of trade mark. Nevertheless, when those criteria are applied, account must be taken of the fact that the perception of the average consumer is not necessarily the same in relation to a three-dimensional mark consisting of the appearance of the product itself as it is in relation to a word or figurative mark consisting of a sign which is independent of the appearance of the products it denotes. Average consumers are not in the habit of making assumptions about the origin of products on the basis of their shape or the shape of their packaging in the absence of any graphic or word element and it could therefore prove more difficult to establish distinctiveness in relation to such a three-dimensional mark than in relation to a word or figurative mark (Procter & Gamble v OHIM, paragraph 36, and Case C‑24/05 P Storck v OHIM [2006] ECR I-5677, paragraphs 24 and 25, and the case-law cited).

44 In those circumstances, only a mark which departs significantly from the norm or customs of the sector and thereby fulfils its essential function of indicating origin is not devoid of any distinctive character for the purposes of Article 7(1)(b) of Regulation No 40/94 (see Storck v OHIM, paragraph 26 and the case-law cited).

45 In the light of those considerations, it is appropriate to examine, first of all, the applicant’s arguments as to the level of attention of the consumer concerned in respect of the appearance of washing tablets and, subsequently, those as to the assessment of each of the marks applied for.

46 The level of attention of the consumer concerned

47 With regard to the consumer concerned in the present cases, the Board of Appeal pointed out that the goods in question are everyday consumer goods directed at all consumers.

48 That view cannot be called into question by the applicant’s argument, which is not substantiated by any precise factual evidence, that those goods, while being everyday consumer goods, are bought by a limited section of the public consisting of consumers who shop on a daily basis.

49 The distinctive character of the mark applied for must therefore be assessed by reference to the assumed expectation of an average consumer who is reasonably well informed and reasonably observant and circumspect (see, to that effect, Square tablet with inlay, paragraph 52, and Rectangular tablet with inlay, paragraph 52, confirmed by Procter & Gamble v OHIM, paragraphs 33 and 35).

50 The average consumer’s level of attention is likely to vary according to the category of goods or services in question (Case C-342/97 Lloyd Schuhfabrik Meyer [1999] ECR I-3819, paragraph 26). In that regard, the Court has already held that the level of attention given by the average consumer to the shape and pattern of washing-machine and dishwasher tablets, being everyday consumer goods, is not high (Square tablet with inlay, paragraph 53, and Rectangular tablet with inlay, paragraph 53).

51 In the present cases, the Board of Appeal pointed out that the level of attention given by the average consumer to the appearance of the goods in question is not high (paragraph 23 of the decision contested in Case T-241/05 and the corresponding paragraphs in the other contested decisions).

52 That view cannot be invalidated by the applicant’s argument based on the price differences between the washing product sold in the form of tablets and that sold in liquid or powder form, or between washing tablets and other everyday consumer products. In fact, the applicant does not provide reasons as to why, although the washing product concerned is an everyday consumer product, the price of that product warrants a different conclusion as to the level of attention paid by the average consumer.

53 Moreover, in the context of assessing the habits of the consumer concerned, the normal marketing practices of the product in question should also be taken into account (see, to that effect, Case T-194/01 Unilever v OHIM (Ovoid tablet) [2003] ECR II-383, paragraph 48). Contrary to what the applicant argues, taking account of the marketing practices prevailing on the market concerned does not depart from the case-law that a particular marketing concept contemplated by the applicant for a mark, which thus depends on the choice of the undertaking concerned and may be changed after registration, is a factor which cannot therefore have any bearing on the assessment of the sign’s registrability (TELE AID, paragraph 42).

54 In the present cases, the Board of Appeal could therefore lawfully take into consideration the fact that the washing tablets are usually sold in packaging bearing the product’s name and on which there are often word marks or figurative marks or other figurative features which may include a depiction of the product (paragraph 24 of the decision contested in Case T-241/05 and the corresponding paragraphs in the other contested decisions).

55 It is clear from the case-law that, generally, the average consumer’s level of attention to the appearance of the products marketed in this way is not high. In such circumstances, it is for the trade mark applicant to show, on the basis of specific and substantiated evidence, that consumers’ habits on the relevant market are different (Ovoid tablet, paragraph 48).

56 Accordingly, it is necessary to examine whether the applicant has demonstrated, on the basis of specific and substantiated evidence, that consumers on the market concerned habitually perceive the appearance of the washing tablet as an indication of its trade origin.

57 First of all, the applicant’s argument based on the interest of the producers concerned in distinguishing the appearance of their products, illustrated by the variety of tablets on the market and by the number of applications lodged for three-dimensional marks in this sector, is not in itself a sufficient ground for concluding that the get-up of those products is normally perceived by the consumer concerned as an indication of their trade origin (see, to that effect, Ovoid tablet, paragraph 50).

58 As regards, next, the applicant’s argument that the tablets can be attached to the packaging, sold in transparent packaging or in packaging in the same shape as the tablet, it should be observed that the applicant is not arguing that it is usual to use these forms of presentation of the goods on the market concerned. That argument does not therefore make it possible to account for consumer habits.

59 Furthermore, as regards the applicant’s argument that the tablets can be depicted on the packaging, it must be observed that this packaging usually comprises a large number of verbal and figurative elements, in particular the name of the product and verbal or figurative marks. That observation is confirmed by examples of packaging of washing-machine and dishwasher tablets presented by the applicant before the Board of Appeal and the Court. In those circumstances, and without excluding the possibility that several marks may appear on the packaging at the same time, the fact that the product is depicted on the packaging does not establish that the consumer pays particular attention to its appearance as being an indication of origin.

60 Finally, in response to the criticism that the Board of Appeal failed to take into consideration certain factors, such as the price of the product and the manner in which the product is presented in advertising, first of all, it should be borne in mind that the applicant does not state how a difference in the price of everyday consumer products can have a bearing on the level of attention paid by the average consumer concerned (see paragraph 51 above).

61 Secondly, the Board of Appeal cannot be accused of failing to analyse the advertisements used in the sector concerned, in view of the fact that the applicant, as it confirmed at the hearing, did not rely on those factors before OHIM. It should be observed that, in the present cases, it is for the trade mark applicant to show that the level of attention paid by the average consumer to the appearance of the product in question on the market concerned is high (see paragraph 54 above).

62 In any event, it cannot be inferred from the examples of advertisements annexed to the applications in Cases T‑29/06 to T‑31/06 that the consumer concerned perceives the images of tablets appearing in the television advertisements otherwise than as showing the product’s features, such as the fact that the detergent in solid form is easy to use and that the tablet contains several coloured ingredients. That is all the more true since the average consumer displays a lower level of attention where he perceives the goods and the marks relating to them in circumstances unconnected with the act of purchase (see, to that effect, Case C-361/04 P Ruiz-Picasso and Others v OHIM [2006] ECR I-643, paragraph 41, and Storck v OHIM, paragraph 72).

63 In the light of those considerations, and without it being necessary to rule on the admissibility of a part of the evidence in question which was not produced before the Board of Appeal, it must be held that the evidence presented by the applicant is not sufficient to establish that the consumer concerned pays particular attention to the appearance of the washing tablet or that he is accustomed to perceiving it as an indication of its commercial origin.

64 Accordingly, the finding of the Board of Appeal that the level of attention paid by the average consumer to the shape and design of the washing tablet is not high must be upheld.

The marks applied for

65 In relation to the assessment of the distinctiveness of each mark applied for, it is necessary to examine whether, as regards the overall impression made by the combination of its shape, colours and design, each mark can be perceived by the consumer concerned as an indication of its commercial origin.

66 That assessment is not incompatible with an examination of each of the product’s individual features in turn (Square tablet with inlay, paragraph 54, and Rectangular tablet with inlay, paragraph 54, confirmed in Procter & Gamble v OHIM, paragraphs 44 and 45).

67 As regards, first of all, the shape of the tablets concerned, it must be observed, as is clear in particular from the examples of tablets presented by the applicant, that the rectangular forms are normally used for detergent tablets. In addition, the simple geometric shapes, such as the square or rectangle, are the obvious ones for a product intended for use in washing machines or dishwashers (Square tablet with inlay, paragraph 56, and Rectangular tablet with inlay, paragraph 56). However, the shape in question, square or cubic with slightly rounded edges, and identical for each tablet concerned, is not so different as to be easily distinguished from the usual shapes of washing preparation tablets.

68 The Board of Appeal was therefore able to take the view, without erring in its assessment, that the shape of the tablets concerned is an obvious one for the product in question.

69 As to the presence of two distinct colours in the washing preparation tablet, the public concerned is used to seeing different colour features in detergent preparations. In addition, since the advertising carried out by the manufacturers of detergents tends to highlight the fact that the colour features indicate the presence of various active ingredients, the consumer concerned sees the presence of coloured elements as a suggestion that the product has certain qualities, and not as an indication of its origin (Case T-337/99 Henkel v OHIM (Red and white round tablet) [2001] ECR II-2597, paragraph 51, and Case T-118/00 Procter & Gamble v OHIM (Square tablet, white with green speckles and pale green) [2001] ECR II-2731, paragraph 61).

70 In the present case, the fact of using two colours in the tablets concerned, namely white, and, depending on the tablet, blue, green or lilac, does not differ from the usual presentation of the products in question. In particular, the applicant does not state in what way those colours are striking for washing preparations.

71 In addition, it does not in any way follow from the contested decisions that the Board of Appeal failed to take into account the presence of two colours. Although that aspect of the tablet is expressly referred to only in the decisions contested in Cases T‑346/05 (paragraph 23) and T‑347/05 (paragraph 24), it should be observed that each contested decision provides a description of the mark applied for, including a reference to the colours, in the first paragraphs of the reasons. In addition, it is clear from the contested decision that the Board of Appeal itself adopted the findings of the examiner, cited in the account of the facts, which deal expressly with the colours.

72 In relation to the colour designs on one face of the tablet, it must be observed that the Court has held that adding an inlay to the upper face of a washing preparation tablet is an obvious way of combining various active ingredients (see, to that effect, Square tablet with inlay, paragraphs 59 and 60, and Rectangular tablet with inlay, paragraphs 59 and 60).

73 Given that the consumer concerned is used to the fact that the colour features indicate the presence of various active ingredients in the tablet (see paragraph 68 above), the point set out in the previous paragraph also applies to the addition of a colour inlay. That point is confirmed, moreover, by examples of packaging of tablets submitted by the applicant to the Court which refer expressly to the fact that the colour inlay, whether round or oval, indicates the presence of a different active ingredient.

74 In the present cases, the Board of Appeal pointed out that the addition of a design to the upper face of each tablet, described as ‘a [rectangular, pentagonal or hexagonal] figure in the shape of a floral [four, five or six] petalled design’ or an ‘unusual [octagonal] shape with rounded corners’ or a ‘five-petalled figure’ design does not confer distinctiveness. The Board of Appeal stated that the addition of an inlay is one of the obvious solutions for combining the various active ingredients and that the combination of the shape and design of the tablet in question consists of the combination of ‘two basic geometric shapes’, or ‘a basic geometric shape and an unusual inlay’, being the most obvious variants of the presentation of the product (paragraphs 28 and 29 of the decision contested in Case T-241/05 and the corresponding paragraphs of the other contested decisions).

75 In that regard, contrary to what the applicant maintains, it does not follow from those findings that the Board of Appeal distorted any of the designs in question by comparing it to a basic geometric shape. The Court has already accepted that an irregular shape may be described as a variant of the basic geometric shape in so far as the differences in relation to that basic shape are not easily perceptible (see, to that effect, Ovoid tablet, paragraphs 55 to 57). In the present context, the Board of Appeal was therefore entitled to compare the symmetrical design of the tablets in question representing a floral four-, five- or six-petalled figure with a variant of a rectangular, pentagonal or hexagonal geometric shape, without distorting that feature.

76 However, given the simplicity of the designs in question and the fact of their being only very slightly different from basic geometric shapes, which are most appropriate for the addition of an active ingredient in the middle of the washing tablet, the Board of Appeal was entitled to find, without erring in its assessment, that each design in question would be perceived as an inlay indicating the presence of another active ingredient.

77 It is therefore not appropriate to uphold the applicant’s argument that the colour design of each tablet concerned cannot be confused with any aspect of the product in question, or the argument that the design contains a feature liable to have a significant effect on the perception of the mark applied for.

78 Finally, the Board of Appeal acted correctly in law in ruling, when assessing the overall impression made by each mark applied for, that the combination of the shape, colours and design in respect of each tablet is a variation of the normal presentation of the product concerned which is not suitable for identifying that product as coming from a specific undertaking and distinguishing it from those of other undertakings, and that the average consumer concerned will perceive each mark applied for only as a form of washing detergent and not as an indication of trade origin (paragraphs 30 to 33 of the decision contested in Case T-241/05 and the corresponding paragraphs of the other contested decisions).

79 It must be held that the addition of a symmetrical sign in the middle of a tablet, such as that represented by each of the designs in question, does not change the tablet’s appearance in any significant way. The combination of the square white shape of the tablets in question with a coloured design, that is, the floral four-, five- or six-petalled images at issue, does not differ significantly from the presentation of the washing tablet which comes readily to mind, in which the various active ingredients are laid out decoratively.

80 In the light of the foregoing, the applicant is not justified in maintaining that the Board of Appeal failed to take into account the overall impression of each mark applied for or that it disregarded the fact that a sign can fulfil several functions at the same time.

81 In addition, in so far as the applicant criticises the wording of the grounds for the decision contested in regard to the assessment of the overall impression of each tablet concerned, it must be observed that it does not follow from those decisions that the Board of Appeal’s assessment was erroneously or excessively demanding. Although the Board of Appeal referred, for example, to the absence of a ‘name, logo or sign’ on the tablet and the fact that there was nothing ‘special, extraordinary or unusual’ about its design, it in fact based its findings on the lack of any feature of the tablet’s presentation capable of influencing the average consumer’s perception and on the absence of a design capable of being noticed and remembered by that consumer (paragraph 31 of the decision contested in Case T-241/05 and the corresponding paragraphs of the other contested decisions).

82 In addition, it must be borne in mind that the absence of distinctiveness in a mark cannot be affected by how many similar shapes are on the market (Case T-335/99 Henkel v OHIM (Red and white rectangular tablet) [2001] ECR II‑2581, paragraph 57, upheld in Joined Cases C-456/01 P and C-457/01 P Henkel v OHIM [2004] ECR I-5089, paragraph 62), or by the absence on the market of shapes identical to those for which registration is sought (see, to that effect, Case T-15/05 De Waele v OHIM (Shape of a sausage) [2006] ECR II-1511, paragraph 40).

83 Therefore, in the present cases, the Board of Appeal was correct to take the view that each mark sought is a variant of the features which come readily to mind in respect of the goods in question, even if a similar combination is not on the market. In any event, the applicant’s argument that there are no tablets containing a colour design on the market cannot therefore succeed.

84 The absence of distinctiveness also cannot be challenged on the ground that the Board of Appeal did not provide specific examples of washing tablets used in trade. Such a finding may be lawfully based on matters of common knowledge arising from practical experience generally acquired from the marketing of general consumer goods, without specific examples having to be provided (see, to that effect, Case T-402/02 Storck v OHIM (Shape of a sweet wrapper) [2004] ECR II-3849, paragraph 58).

85 As regards the arguments relating to the earlier registrations made by OHIM, it should be borne in mind that, according to established case-law, the lawfulness of the decisions of the Board of Appeal must be assessed solely on the basis of Regulation No 40/94 and not on the basis of any decision-making practice prior to those decisions (see Case C-173/04 P Deutsche SiSi-Werke v OHIM [2006] ECR I-551, paragraph 48 and the case-law cited).

86 In any event, in the present cases, the earlier registrations relied on by the applicant do not make it possible to establish the distinctiveness of the marks applied for.

87 First of all, as regards the registrations as Community marks of basic geometric shapes and floral images, it should be borne in mind that the average consumer’s perception is not the same in relation to a figurative sign which is independent of the appearance of the products it denotes as it is in relation to the features of a three-dimensional sign which coincides with the appearance of the product (see paragraph 43 above). Secondly, the alleged resemblance between the six-petalled sign of certain marks applied for (Cases T‑241/05, T‑262/05 and T‑346/05) and the Ariel logo is not easily perceptible. Thirdly, in respect of the three-dimensional Community marks having the shape of tablets containing features resembling a letter ‘s’, a ‘yin-yang’ symbol and a drop of water, it must be observed that those figures contain features which are not comparable to those of the marks applied for.

88 In relation to the registration of certain relevant marks by the Benelux Trade Marks Office, it is settled case-law that the registrations already made in the Member States are factors which may be taken into consideration, without being given decisive weight, in the registration of a Community trade mark (see, to that effect, Red and white round tablet, paragraph 58, and the case-law cited). However, the applicant does not put forward any argument which, in this case, could be derived from the decision of the Benelux Trade Marks Office.

89 Finally, as regards the criticism which the applicant levels at the findings relating to the need to keep basic geometric forms available, contained in seven of the nine contested decisions (see, by way of illustration, paragraphs 35 to 39 of the decision contested in Case T‑241/05), it must be observed that that argument, while being undoubtedly unfounded in law, is mentioned explicitly in the decisions only for the sake of completeness and therefore cannot justify annulment of those decisions.

90 It follows that the argument based on those inappropriate references must be rejected as irrelevant.

91 In the light of the foregoing, it must be held that the Board of Appeal established to the requisite legal standard that each of the marks applied for fails, as regards the overall impression produced by the combination of the shape, colours and design of the tablets in question, to enable the average consumer concerned to identify the trade origin of the goods in question when he makes his selection at the time of purchase.

92 Accordingly, the actions must be dismissed as unfounded.

Costs

93 Under Article 87(2) of the Rules of Procedure of the Court, the unsuccessful party is to be ordered to pay the costs if they have been applied for in the successful party’s pleadings. Since the applicant has been unsuccessful, it must be ordered to pay the costs, in accordance with the forms of order sought by OHIM.

On those grounds,

THE COURT OF FIRST INSTANCE (Fourth Chamber)

hereby:

1. Dismisses the actions;

2. Orders the applicant to pay the costs.

Delivered in open court in Luxembourg on 23 May 2007.