JUDGMENT OF THE GENERAL COURT (Sixth Chamber)

16 January 2014 (*)

(Community trade mark – Opposition proceedings – Application for the Community figurative mark FOREVER – Earlier national figurative mark 4 EVER – Relative ground for refusal – Likelihood of confusion – Similarity of the signs – Article 8(1)(b) of Regulation (EC) No 207/2009 – Genuine use of the earlier mark – Article 42(2) and (3) of Regulation No 207/2009)

In Case T‑528/11,

Aloe Vera of America, Inc., established in Dallas, Texas (United States), represented by R. Niebel and F. Kerl, lawyers,

applicant,

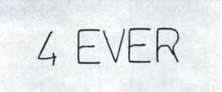

v

Office for Harmonisation in the Internal Market (Trade Marks and Designs) (OHIM), represented by J. Crespo Carrillo, acting as Agent,

defendant,

the other party to the proceedings before the Board of Appeal of OHIM, intervener before the General Court, being

Detimos – Gestão Imobiliária, SA, established in Carregado (Portugal), represented by V. Caires Soares, lawyer,

ACTION brought against the decision of the Fourth Board of Appeal of OHIM of 8 August 2011 (Case R 742/2010‑4), relating to opposition proceedings between Diviril – Distribuidora de Viveres do Ribatejo, Lda and Aloe Vera of America, Inc.,

THE GENERAL COURT (Sixth Chamber),

composed of S. Frimodt Nielsen, President, F. Dehousse and A. Collins (Rapporteur), Judges,

Registrar: E. Coulon,

having regard to the application lodged at the Court Registry on 6 October 2011,

having regard to the response of OHIM lodged at the Court Registry on 31 January 2012,

having regard to the response of the intervener lodged at the Court Registry on 27 January 2012,

having regard to the change in the composition of the Chambers of the Court,

having regard to the fact that no application for a hearing was submitted by the parties within the period of one month from notification of closure of the written procedure, and having therefore decided, acting upon a report of the Judge‑Rapporteur, to rule on the action without an oral procedure pursuant to Article 135a of the Rules of Procedure of the General Court,

gives the following

Judgment

Background to the dispute

1 On 22 December 2006, the applicant, Aloe Vera of America, Inc., filed an application for registration of a Community trade mark with the Office for Harmonisation in the Internal Market (Trade Marks and Designs) (OHIM) pursuant to Council Regulation (EC) No 40/94 of 20 December 1993 on the Community trade mark (OJ 1994 L 11, p. 1), as amended (replaced by Council Regulation (EC) No 207/2009 of 26 February 2009 on the Community trade mark (OJ 2009 L 78, p. 1)).

2 Registration as a mark was sought for the following figurative sign:

3 The goods in respect of which registration was sought are in, inter alia, Class 32 of the Nice Agreement concerning the International Classification of Goods and Services for the Purpose of the Registration of Marks of 15 June 1957, as revised and amended, and correspond to the following description: ‘Aloe vera juice, aloe vera gel drinks and aloe vera pulp; aloe vera juice mixed with fruit juice(s); and bottled spring water’.

4 The Community trade mark application was published in Community Trade Marks Bulletin No 30/2007 of 2 July 2007.

5 On 28 September 2007, Diviril – Distribuidora de Viveres do Ribatejo, Lda filed a notice of opposition pursuant to Article 42 of Regulation No 40/94 (now Article 41 of Regulation No 207/2009) against registration of the mark applied for in respect of the goods referred to in paragraph 3 above.

6 The opposition was based on the earlier Portuguese figurative mark reproduced below, which was filed on 27 January 1994, registered on 11 April 1995 under the number 297697 and renewed on 9 August 2005 in respect of ‘Juices, lime lemon juices – exclusively for exportation’ in Class 32 of the Nice Agreement:

7 The grounds relied on in support of the opposition were those set out in Article 8(1)(a) of Regulation No 40/94 (now Article 8(1)(a) of Regulation No 207/2009) and Article 8(1)(b) of Regulation No 40/94 (now Article 8(1)(b) of Regulation No 207/2009).

8 On 19 October 2007, the earlier mark was transferred to the intervener, Detimos – Gestão Imobiliária, SA, which is the successor in title to Diviril.

9 On 20 April 2009, the applicant requested the intervener to furnish proof of genuine use of the earlier mark.

10 By letter of 19 May 2009, OHIM requested that the intervener provide that proof within a period of two months, that is to say by 20 July 2009 at the latest.

11 In reply to that letter, the intervener submitted a series of invoices on 12 June 2009.

12 By decision of 22 April 2010, the Opposition Division upheld the opposition and rejected the application for registration of the Community trade mark.

13 On 30 April 2010, the applicant filed a notice of appeal with OHIM, under Articles 58 to 64 of Regulation No 207/2009, against the decision of the Opposition Division.

14 By decision of 8 August 2011 (‘the contested decision’), the Fourth Board of Appeal of OHIM dismissed the appeal. First, it found that the relevant public consisted of average Portuguese consumers. Second, it found that the intervener had proved sufficiently that the earlier mark had been put to genuine use in Portugal in the course of the relevant period of five years. Third, it found that the goods concerned were in part identical and in part similar. Fourth, it pointed out that there was a low degree of visual similarity between the marks at issue and that those marks were phonetically identical for that part of the relevant public which had a certain knowledge of the English language and similar to an average degree for the remainder of the relevant public. As regards the conceptual comparison, it found that the marks at issue were identical for that part of the relevant public which was familiar with English and neutral for the remainder of the relevant public. Fifth, in the context of the global assessment it concluded, having, inter alia, pointed out that the earlier mark had a normal distinctive character, that there was a likelihood of confusion within the meaning of Article 8(1)(b) of Regulation No 207/2009.

Forms of order sought

15 The applicant claims that the Court should:

– annul the contested decision;

– order OHIM and the intervener to pay the costs.

16 OHIM contends that the Court should:

– dismiss the action;

– order the applicant to pay the costs.

17 The intervener contends that the Court should:

– dismiss the action;

– order the applicant to pay the costs which the intervener incurred in all the proceedings.

Substance

18 In support of its action, the applicant relies on two pleas in law alleging, first, infringement of Article 42(2) and (3) of Regulation No 207/2009 and, second, infringement of Article 8(1)(b) of that regulation.

The first plea: infringement of Article 42(2) and (3) of Regulation No 207/2009

19 The applicant claims, in contrast to the Board of Appeal’s assessment, that the invoices submitted by the intervener in the course of the administrative procedure were insufficient for the purpose of furnishing proof of genuine use of the earlier mark within the meaning of Article 42(2) and (3) of Regulation No 207/2009.

20 OHIM and the intervener agree with the assessment of the Board of Appeal.

21 It should be noted that, pursuant to Article 42(2) and (3) of Regulation No 207/2009, an applicant for a Community trade mark, against which an opposition is filed, may require proof that the earlier national mark, relied on in support of that opposition, has been put to genuine use during the five years preceding the date of publication of the application.

22 Furthermore, under Rule 22(3) of Commission Regulation (EC) No 2868/95 of 13 December 1995 implementing Regulation No 40/94 (OJ 1995 L 303, p. 1), as amended, proof of use must relate to the place, time, extent and nature of use of the earlier mark.

23 In accordance with settled case-law, it is apparent from the abovementioned provisions, and also taking into account recital 10 in the preamble to Regulation No 207/2009, that the ratio legis of the provision requiring that the earlier mark must have been put to genuine use if it is to be capable of being used in opposition to a trade mark application is to restrict the number of conflicts between two marks, where there is no good commercial justification resulting from a function actually performed by the mark on the market. However, the purpose of those provisions is not to assess commercial success or to review the economic strategy of an undertaking, nor are they intended to restrict trade-mark protection to the case where large-scale commercial use has been made of the marks (see, to that effect, Case T‑203/02 Sunrider v OHIM – Espadafor Caba (VITAFRUIT) [2004] ECR II‑2811, paragraphs 36 to 38 and the case-law cited).

24 There is genuine use of a trade mark where the mark is used in accordance with its essential function, which is to guarantee the identity of the origin of the goods or services for which it is registered, in order to create or preserve an outlet for those goods or services; genuine use does not include token use for the sole purpose of preserving the rights conferred by the mark (see, by analogy, Case C‑40/01 Ansul [2003] ECR I‑2439, paragraph 43). Furthermore, the condition relating to genuine use of the trade mark requires that the mark, as protected in the relevant territory, be used publicly and outwardly (VITAFRUIT, cited in paragraph 23 above, paragraph 39; see also, to that effect and by analogy, Ansul, paragraph 37).

25 When assessing whether use of the trade mark is genuine, regard must be had to all the facts and circumstances relevant to establishing whether the commercial exploitation of the mark is real, particularly the use regarded as warranted in the economic sector concerned as a means of maintaining or creating a share in the market for the goods or services protected by the mark, the nature of those goods or services, the characteristics of the market and the scale and frequency of use of the mark (VITAFRUIT, cited in paragraph 23 above, paragraph 40; see also, by analogy, Ansul, cited in paragraph 24 above, paragraph 43).

26 As to the extent of the use to which the earlier trade mark has been put, account must be taken, in particular, of the commercial volume of the overall use, as well as of the length of the period during which the mark was used and the frequency of use (VITAFRUIT, cited in paragraph 23 above, paragraph 41, and Case T‑334/01 MFE Marienfelde v OHIM – Vétoquinol (HIPOVITON) [2004] ECR II‑2787, paragraph 35).

27 To examine whether an earlier trade mark has been put to genuine use in a particular case, a global assessment must be carried out, which takes into account all the relevant factors of that case. That assessment entails a degree of interdependence between the factors taken into account. Thus, the fact that the commercial volume achieved under the mark was not high may be offset by a high intensity or some settled period of use of that mark or vice versa (VITAFRUIT, cited in paragraph 23 above, paragraph 42, and HIPOVITON, cited in paragraph 26 above, paragraph 36).

28 The turnover and the volume of sales of the goods under the earlier trade mark cannot be assessed in absolute terms but must be looked at in relation to other relevant factors, such as the volume of business, production or marketing capacity or the degree of diversification of the undertaking using the trade mark and the characteristics of the goods or services on the relevant market. As a result, use of the earlier mark need not always be quantitatively significant in order to be deemed genuine (VITAFRUIT, cited in paragraph 23 above, paragraph 42, and HIPOVITON, cited in paragraph 26 above, paragraph 36). Even minimal use can therefore be sufficient to be classified as genuine, provided that it is justified, in the economic sector concerned, to maintain or create market share for the goods or services protected by the mark. It follows that it is not possible to determine a priori, and in the abstract, what quantitative threshold should be chosen in order to determine whether use is genuine or not. A de minimis rule, which would not allow OHIM or, on appeal, the General Court, to appraise all the circumstances of the dispute before it, cannot therefore be laid down (Case C‑416/04 P Sunrider v OHIM [2006] ECR I‑4237, paragraph 72).

29 Furthermore, genuine use of a trade mark cannot be proved by means of probabilities or suppositions, but must be demonstrated by solid and objective evidence of actual and sufficient use of the trade mark on the market concerned (Case T‑39/01 Kabushiki Kaisha Fernandes v OHIM – Harrison (HIWATT) [2002] ECR II‑5233, paragraph 47, and Case T‑356/02 Vitakraft-Werke Wührmann v OHIM – Krafft (VITAKRAFT) [2004] ECR II‑3445, paragraph 28).

30 Lastly, it must be noted that, under point (a) of the second subparagraph of Article 15(1) of Regulation No 207/2009 in conjunction with Article 43(2) and (3) of that regulation, proof of genuine use of an earlier national or Community trade mark which forms the basis of an opposition against a Community trade mark application also includes proof of use of the earlier mark in a form differing in elements which do not alter the distinctive character of that mark in the form in which it was registered (see Case T‑29/04 Castellblanch v OHIM – Champagne Roederer (CRISTAL CASTELLBLANCH) [2005] ECR II‑5309, paragraph 30 and the case-law cited).

31 It is in the light of those considerations that it must be examined whether the Board of Appeal was right to find, in paragraphs 18 to 25 of the contested decision, that the intervener had sufficiently proved that the earlier mark had been put to genuine use in Portugal during the five‑year period referred to in Article 42(2) and (3) of Regulation No 207/2009, which, in the present case, ran from 2 July 2002 to 1 July 2007 (‘the relevant period’).

32 In reply to OHIM’s letter of 19 May 2009 (see paragraph 10 above), the intervener submitted 27 invoices issued by Diviril Comercio – Comercialização de produtos alimentares, Lda, a Portuguese company linked to Diviril, to the Opposition Division.

33 Of those 27 invoices, 12 relate to the relevant period and show that the earlier mark was put to use between 30 March 2005 and 8 June 2007, namely for a period of about 26 months (‘the 12 invoices’).

34 The goods covered by the 12 invoices are, inter alia, called ‘4Ever Lima Limão’, ‘4Ever Laranja’ or ‘4Ever Ananás’ and are sold in 1.5 litre bottles, which makes it possible to conclude that they are fruit juices, that is to say goods in respect of which the earlier mark is registered and on which the opposition was based. Those invoices also refer to sales, in 1.5 litre bottles, of beverages called ‘4Ever Gasosa’ and ‘4Ever Cola’.

35 It is true, as the applicant rightly points out, that on the 12 invoices the element ‘4ever’ is written in ordinary characters and is not therefore an exact reproduction of the earlier mark. However, the differences in relation to that mark are only very slight, as the figurative aspect of the earlier mark is quite banal inasmuch as the number 4 and the word ‘ever’ appear in rather ordinary characters, with the exception of the letter ‘r’, which is slightly stylized, and inasmuch as that mark does not include a colour, a logo or a striking graphic element. As was rightly stated in paragraph 24 of the contested decision, the abovementioned differences do not therefore in any way alter the distinctive character of the earlier mark in the form in which it was registered and do not adversely affect the function of identification which it fulfils. Consequently, contrary to what the applicant claims, the intervener cannot be criticised for not providing any additional evidence containing the ‘exact representation’ of the earlier mark.

36 It is also apparent from the 12 invoices, which are written in Portuguese, that the deliveries of the bottles of fruit juice were intended for 7 customers located in various places in Portugal. There is therefore no doubt that those goods were intended for the Portuguese market, which is the relevant market.

37 Furthermore, those invoices establish that the value of the fruit juices marketed under the earlier mark, between 30 March 2005 and 8 June 2007, to customers in Portugal, amounted to EUR 2 604, exclusive of value added tax, corresponding to the sale of 4 968 bottles. If the beverages called ‘4Ever Gasosa’ and ‘4Ever Cola’ are included, the number of bottles sold increases to 8 628 and the turnover, exclusive of value added tax, increases to EUR 3 856.

38 As OHIM correctly points out in paragraph 22 of the contested decision, although those figures are rather low, the invoices submitted suggest that the goods to which they refer were marketed relatively regularly throughout a period of approximately 26 months, a period which is neither particularly short nor particularly close to the publication of the Community trade mark application filed by the applicant (see, to that effect, VITAFRUIT, cited in paragraph 23 above, paragraph 48).

39 The sales in question constitute use which objectively is such as to create or preserve an outlet for the goods concerned and which entails a volume of sales which, in relation to the period and frequency of use, is not so low that it may be concluded that the use is merely token, minimal or notional for the sole purpose of preserving the rights conferred by the mark (see, to that effect, VITAFRUIT, cited in paragraph 23 above, paragraph 49). In that regard, account must be taken inter alia of the fact that the territory of Portugal is relatively small in size and population.

40 The same is true of the fact that the 12 invoices were made out to only seven customers. It is sufficient that the trade mark is used publicly and outwardly and not solely within the undertaking which owns the earlier trade mark or within a distribution network owned or controlled by that undertaking (VITAFRUIT, cited in paragraph 23 above, paragraph 50).

41 Consequently, although the extent of use to which the earlier mark was put is relatively limited, the Board of Appeal did not err in concluding, in the contested decision, that the evidence submitted by the applicant was sufficient for a finding of genuine use.

42 Contrary to what the applicant claims, the Board of Appeal did not rely on ‘mere assumptions and probabilities’ in arriving at that conclusion. The Opposition Division and the Board of Appeal relied, in that regard, on the 12 invoices and on considerations which are fully in accordance with the case-law, in particular the judgment in VITAFRUIT, cited in paragraph 23 above, which was confirmed by the judgment in Sunrider v OHIM, cited in paragraph 28 above. In VITAFRUIT, cited in paragraph 23 above, the General Court held that the delivery, confirmed by about 10 invoices, to a single customer in Spain of 3 516 bottles of concentrated fruit juices, representing sales of approximately EUR 4 800, in the course of a period of 11 and a half months constituted genuine use of the earlier trade mark concerned.

43 In that context, the applicant cannot derive an argument from the fact that, in paragraph 22 of the contested decision, the Board of Appeal stated that ‘it [could] not be assumed that the invoices furnished [were] all of the invoices for sales in the relevant five year period’ and that ‘[i]n the case of proof of use consisting of invoices, opponents usually furnish only samples of the invoices issued’. As OHIM quite rightly points out, these are just common sense considerations since the proprietor of an earlier mark cannot be required to furnish evidence of each transaction carried out under that mark in the relevant five-year period referred to in Article 42(2) of Regulation No 207/2009. What is important, if it relies on invoices as evidence, is that it submits a quantity of examples which makes it possible to discount any possibility of merely token use of that mark and, consequently, is sufficient to prove that it has been genuinely used. Furthermore, it must be pointed out that, in the present case, in the observations which it submitted to the Board of Appeal on 17 March 2011, the intervener expressly stated that the 12 invoices were samples.

44 In the light of all of the foregoing considerations, the first plea must be rejected as unfounded.

The second plea: infringement of Article 8(1)(b) of Regulation No 207/2009

45 The applicant submits, in essence, that the Board of Appeal was not justified in taking the pronunciation of the marks at issue by English-speaking consumers into consideration for the purposes of the phonetic comparison and that it did not correctly identify the conceptual and visual differences between those marks. Consequently, the Board of Appeal erroneously found that there was a likelihood of confusion in the present case.

46 Article 8(1)(b) of Regulation No 207/2009 provides that, upon opposition by the proprietor of an earlier trade mark, the trade mark applied for must not be registered if because of its identity with, or similarity to, an earlier trade mark and the identity or similarity of the goods or services covered by the trade marks, there exists a likelihood of confusion on the part of the public in the territory in which the earlier trade mark is protected. The likelihood of confusion includes the likelihood of association with the earlier trade mark.

47 Furthermore, under Article 8(2)(a)(ii) of Regulation No 207/2009, ‘earlier trade marks’ means trade marks registered in a Member State with a date of application for registration which is earlier than the date of application for registration of the Community trade mark.

48 According to settled case-law, the risk that the public might believe that the goods or services in question come from the same undertaking or from economically-linked undertakings constitutes a likelihood of confusion. According to the same case-law, the likelihood of confusion must be assessed globally, according to the perception which the relevant public has of the signs and the goods or services in question, account being taken of all factors relevant to the circumstances of the case, including the interdependence between the similarity of the signs and that of the goods or services covered (see Case T‑162/01 Laboratorios RTB v OHIM – Giorgio Beverly Hills (GIORGIO BEVERLY HILLS) [2003] ECR II‑2821, paragraphs 30 to 33 and the case-law cited).

49 For the purposes of applying Article 8(1)(b) of Regulation No 207/2009, a likelihood of confusion presupposes both that the two marks are identical or similar and that the goods or services which they cover are identical or similar. Those conditions are cumulative (see Case T‑316/07 Commercy v OHIM – easyGroup IP Licensing (easyHotel) [2009] ECR II‑43, paragraph 42 and the case-law cited).

50 It is in the light of those considerations that it must be examined whether the Board of Appeal was right to find that there was a likelihood of confusion between the earlier mark and the mark applied for.

The relevant public and its level of attentiveness

51 The Board of Appeal was right to find, in paragraphs 17 and 32 of the contested decision, respectively, that the relevant public consisted of average Portuguese consumers and that the level of attentiveness of that public was average. The applicant expressly concurs with those findings in its written pleadings.

The comparison of the goods

52 In paragraphs 26 to 28 of the contested decision, the Board of Appeal correctly found, without being contradicted by the applicant, that the goods concerned were in part identical and in part similar.

The comparison of the signs

53 The global assessment of the likelihood of confusion, in relation to the visual, phonetic or conceptual similarity of the signs in question, must be based on the overall impression given by the signs, bearing in mind, in particular, their distinctive and dominant components. The perception of the marks by the average consumer of the goods or services in question plays a decisive role in the global appreciation of such likelihood of confusion. In this regard, the average consumer normally perceives a mark as a whole and does not engage in an analysis of its various details (see Case C‑334/05 P OHIM v Shaker [2007] ECR I‑4529, paragraph 35 and case-law cited).

54 Assessment of the similarity between two marks means more than taking just one component of a composite trade mark and comparing it with another mark. On the contrary, the comparison must be made by examining each of the marks in question as a whole, which does not mean that the overall impression conveyed to the relevant public by a composite trade mark may not, in certain circumstances, be dominated by one or more of its components (see OHIM v Shaker, cited in paragraph 53 above, paragraph 41 and the case-law cited). It is only if all the other components of the mark are negligible that the assessment of the similarity can be carried out solely on the basis of the dominant element (OHIM v Shaker, cited in paragraph 53 above, paragraph 42, and judgment of 20 September 2007 in Case C‑193/06 P Nestlé v OHIM, not published in the ECR, paragraph 42). That could be the case, in particular, where that component is capable on its own of dominating the image of that mark which members of the relevant public keep in their minds, so that all the other components are negligible in the overall impression created by that mark (Nestlé v OHIM, paragraph 43).

– The visual comparison

55 The Board of Appeal found, in paragraph 29 of the contested decision, that there was a low degree of visual similarity between the marks at issue.

56 The applicant claims that there is no visual similarity between the marks at issue. It submits, first, that there is only a low degree of visual similarity between the earlier mark and the word element of the mark applied for. Second, the figurative element of the mark applied for is individual and original. Third, the distinctiveness of the figurative element of the mark applied for, which represents a bird of prey, is as great as that of the word element of the same mark, such that the latter cannot be regarded as dominant.

57 OHIM and the intervener dispute the applicant’s arguments.

58 It must be stated that the marks at issue have in common the letters ‘e’, ‘v’, ‘e’ and ‘r’, which appear in that order and constitute almost all of the earlier mark and the second part of the word element of the mark applied for. There are therefore elements of visual similarity between those marks, as the applicant, moreover, expressly acknowledges.

59 The marks at issue are differentiated by the fonts used to represent their respective word elements, the slightly stylised shape of the letter ‘r’ in the earlier mark, the presence of the number ‘4’ at the beginning of the earlier mark, the representation of a bird of prey in the upper part of the mark applied for and the presence, at the beginning of the word element of the mark applied for, of the letters ‘f’, ‘o’ and ‘r’, thus forming with the other letters of the word element the English word ‘forever’.

60 Those differences, although they are clearly not ancillary, are not, however, so significant as to cancel out the slight visual similarity between the marks at issue resulting from the elements referred to in paragraph 58 above.

61 That finding cannot be called in question by the arguments which the applicant bases on the figurative element of the mark applied for (see paragraph 56 above). First, as the intervener rightly points out, that figurative element, namely the relatively banal representation of a bird of prey, is not as original and striking as the applicant suggests. Second, in the case of a mark consisting of both word and figurative elements, the word elements must generally be regarded as more distinctive than the figurative elements, or even as dominant, in particular since members of the relevant public will keep the word element in their minds to identify the mark concerned, the figurative elements being perceived more as decorative elements (see, to that effect, judgment of 15 November 2011 in Case T‑434/10 Hrbek v OHIM – Outdoor Group (ALPINE PRO SPORTSWEAR & EQUIPMENT), not published in the ECR, paragraphs 55 and 56; judgment of 31 January 2012 in Case T‑205/10 Cervecería Modelo v OHIM – Plataforma Continental (LA VICTORIA DE MEXICO), not published in the ECR, paragraphs 38 and 46; and judgment of 2 February 2012 in Case T‑596/10 Almunia Textil v OHIM – FIBA-Europe (EuroBasket), not published in the ECR, paragraph 36).

62 In the light of those considerations and in view of the fact that the average consumer will, as a general rule, place his trust in the imperfect picture of the marks that he has kept in his mind (see, to that effect, Case C‑342/97 Lloyd Schuhfabrik Meyer [1999] ECR I‑3819, paragraph 26), the Board of Appeal’s assessment concerning the existence of a low degree of visual similarity between the marks at issue must be confirmed.

– The phonetic comparison

63 In paragraph 30 of the contested decision, the Board of Appeal stated the following:

‘A part of the public, that part having a certain knowledge of English will pronounce the two marks identically. Just that part of the Portuguese public not familiar with English will pronounce the two marks differently, as CU/A/TRO/E/VER and FO/RE/VER. In the first case the marks are aurally identical; in the second case, simply similar to a medium degree.’

64 The applicant disputes that analysis by submitting that, if an opposition is based solely on a national trade mark, the likelihood of confusion has to be assessed in relation to the linguistic rules and the rules of pronunciation of the language of the target public, namely that of the Member State in which that mark is protected. It takes the view that, in the present case, only the understanding of the marks by Portuguese-speaking consumers may therefore be taken into account. It points out that it is far from certain that the average Portuguese consumer will recognise the combination of the number 4 and the word ‘ever’ as being derived from English rather than as a fanciful word. In any event, that consumer will not necessarily pronounce the earlier mark according to English rules of pronunciation. Furthermore, it will still be necessary to establish that a majority of the relevant public is able to pronounce the word in question correctly. The applicant also disputes that the marks at issue are ‘similar to a medium degree’ for the part of the relevant public which is not familiar with the English language and which will therefore pronounce the earlier mark as ‘quatroever’.

65 OHIM and the intervener reject the applicant’s arguments.

66 It must be pointed out that, although it is correct that the likelihood of confusion must be assessed in relation to the public in the territory in which the earlier mark was registered, in the present case Portuguese territory, the fact none the less remains that, in the course of that exercise, the particular characteristics and knowledge of that public must be taken into consideration.

67 In this respect, with regard to the present case, as the intervener rightly states, the view in particular cannot be taken that the average Portuguese consumer will understand only trade marks written in Portuguese or will automatically assume that trade marks consisting of numbers and of words written in English should be understood and pronounced as if they were Portuguese.

68 More generally, it is incorrect to claim, as the applicant does, that ‘English is not generally spoken and understood by the Portuguese customers’. A knowledge of that language, admittedly to varying degrees, is relatively widespread in Portugal. Although it cannot be claimed that the majority of the Portuguese public speaks English fluently, it may, however, reasonably be presumed that a significant part of that public has at the very least a basic knowledge of that language which enables it to understand and to pronounce English words as basic and everyday as ‘forever’ or to pronounce numbers below 10 in English (see, to that effect, judgment of 28 October 2009 in Case T‑273/08 X‑Technology R & D Swiss v OHIM – Ipko-Amcor (First-On-Skin), not published in the ECR, paragraph 37; judgment of 5 October 2011 in Case T‑118/09 La Sonrisa de Carmen and Bloom Clothes v OHIM – Heldmann (BLOOMCLOTHES), not published in the ECR, paragraph 38; and judgment of 6 June 2013 in Case T‑411/12 Celtipharm v OHIM – Alliance Healthcare France (PHARMASTREET), not published in the ECR, paragraph 34).

69 Furthermore, it may also reasonably be presumed, having regard, in particular, to the very widespread use of the language known as ‘SMS language’ in the course of communication on the Internet by means of instant messaging or electronic mail, in Internet forums and blogs or even in online games, that the number 4, if it is associated with an English word, will itself generally be read in English and understood as referring to the English preposition ‘for’ (see, to that effect, judgment of 7 May 2009 in Case T‑414/05 NHL Enterprises v OHIM – Glory & Pompea (LA KINGS), not published in the ECR, paragraph 31). As the intervener rightly points out, a Portuguese trade mark which includes a number will generally be read in Portuguese only when that number is accompanied by one or more Portuguese words as is the case, for example, with the Portuguese trade mark Companhia das 4 Patas. The word ‘ever’ in the earlier mark is not part of the vocabulary of the Portuguese language.

70 It follows that the Board of Appeal was right to find that the part of the relevant public which has some knowledge of the English language, knowledge which, for the reasons set out in paragraphs 68 and 69 above, does not necessarily have to be extensive, will read and pronounce the earlier mark in the same way as the mark applied for in so far as the latter uses the English word ‘forever’.

71 It is true that the part of the relevant public referred to above may not pronounce the word ‘forever’ in exactly the same way as persons whose mother tongue is English. However, the applicant cannot derive an argument from that finding since that word cannot be regarded as requiring an in-depth knowledge of or a particular aptitude for English in order to be capable of being pronounced intelligibly.

72 Lastly, it must be held that, in the light of the fact that the marks at issue share the same ending ‘ever’, the Board of Appeal did not err in finding that those marks were phonetically similar to an average degree for the part of the relevant public with no knowledge of the English language.

– The conceptual comparison

73 In paragraph 31 of the contested decision, the Board of Appeal stated the following:

‘… the conceptual comparison depends on the part of the public considered: the part of the public familiar with English will see the same idea of “without end, eternal” in the two marks (thus conceptually identical), whilst the part not familiar with English will not associate the marks conceptually’.

74 The applicant claims that the average Portuguese consumer will not perceive any conceptual similarity between the marks at issue. It submits, first, that neither of those marks will have any meaning for Portuguese consumers who do not speak English. Second, even Portuguese consumers who have a sufficient knowledge of English will regard the marks at issue as completely dissimilar since they will not perceive any connection between the term ‘forever’ in the mark applied for and the number 4. Third, account must be taken of the fact that the figurative element of the mark applied for, which represents a bird of prey, forms part of the conceptual meaning of that mark on account of its size and of the clear message which it conveys and has no equivalent in the earlier mark.

75 OHIM and the intervener dispute the applicant’s arguments.

76 First, as regards the part of the relevant public which has no knowledge of the English language, it is sufficient to state that the applicant shares the assessment, which is, moreover, well founded, of the Board of Appeal that the marks at issue are conceptually neutral.

77 Second, the part of the relevant public which has a sufficient knowledge of the English language will perceive clearly a link between, first, the English word ‘forever’ and, second, the combination of the number 4 – which, for the reasons set out in paragraphs 68 and 69 above, it will associate with the English preposition ‘for’ – with the English word ‘ever’, a combination which refers to the same word ‘forever’.

78 That finding cannot be called in question by the applicant’s argument relating to the representation of a bird of prey contained in the mark applied for. As OHIM rightly submits, that representation does not introduce any particularly specific or striking concept of its own or add to, clarify or alter the meaning of the English word ‘forever’.

79 It follows from the foregoing that the Board of Appeal did not err in assessing the similarities between the mark applied for and the earlier mark.

The likelihood of confusion

80 A global assessment of the likelihood of confusion implies some interdependence between the factors taken into account, and in particular between the similarity of the trade marks and the similarity of the goods or services concerned. Accordingly, a lesser degree of similarity between those goods or services may be offset by a greater degree of similarity between the marks, and vice versa (Case C‑39/97 Canon [1998] ECR I‑5507, paragraph 17, and Joined Cases T‑81/03, T‑82/03 and T‑103/03 Mast-Jägermeister v OHIM – Licorera Zacapaneca (VENADO with frame and others) [2006] ECR II‑5409, paragraph 74).

81 In paragraph 32 of the contested decision, the Board of Appeal, after pointing out that the distinctive character of the earlier mark was normal, reiterating the conclusions it had reached as regards the comparison of the marks at issue (see paragraphs 55, 63 and 73 above), stating that the level of attentiveness of the relevant public was average and reiterating that the goods concerned were in part identical and in part similar, found that there was a likelihood of confusion between those marks assessed as a whole.

82 The applicant disputes that finding by referring to the alleged differences which it has identified between the marks at issue.

83 OHIM and the intervener share the Board of Appeal’s analysis.

84 It must be borne in mind that the Board of Appeal correctly stated that the goods at issue were in part identical and in part similar, that there was a low degree of visual similarity between the marks at issue, that, phonetically, those marks were identical for that part of the relevant public with some knowledge of English and similar to an average degree for that part of the relevant public with no such knowledge, and that, conceptually, those marks were identical for that part of the relevant public with some knowledge of English and neutral for that part of the relevant public with no such knowledge. Having regard to the fact, which, moreover, the applicant does not dispute, that the distinctive character of the earlier mark is normal, to the average level of attentiveness of the relevant public and to the cumulative nature of the conditions relating to the similarity of the goods and services and to the similarity of the marks, it must be held, in the context of a global assessment, that the Board of Appeal was right to find that there was a likelihood of confusion between the marks at issue.

85 In view of the foregoing the second plea must be rejected and the action must be dismissed in its entirety.

Costs

86 Under Article 87(2) of the Rules of Procedure of the General Court, the unsuccessful party is to be ordered to pay the costs if they have been applied for in the successful party’s pleadings.

87 Since the applicant has been unsuccessful, it must be ordered to pay the costs, in accordance with the forms of order sought by OHIM and the intervener.

88 In addition, the intervener has contended that the applicant should be ordered to pay the costs which it incurred in the proceedings before OHIM.

89 In that regard, it should be borne in mind that, under Article 136(2) of the Rules of Procedure, ‘[c]osts necessarily incurred by the parties for the purposes of the proceedings before the Board of Appeal … shall be regarded as recoverable costs’. It follows that costs incurred in relation to opposition proceedings before the Opposition Division cannot be regarded as recoverable costs (see, to that effect, Case T‑147/03 Devinlec v OHIM – TIME ART (QUANTUM) [2006] ECR II‑11, paragraph 115, and judgment of 16 January 2008 in Case T‑112/06 Inter-Ikea v OHIM – Waibel (idea), not published in the ECR, paragraph 88).

90 Consequently, the intervener’s head of claim to the effect that the applicant should be ordered to pay the costs incurred before the Opposition Division must be rejected.

91 In those circumstances, the applicant must be ordered, in addition to bearing its own costs and paying those of OHIM, to pay the costs of the intervener, with the exception of the costs incurred by the latter in the proceedings before the Opposition Division.

On those grounds,

THE GENERAL COURT (Sixth Chamber)

hereby:

1. Dismisses the action;

2. Orders Aloe Vera of America, Inc. to pay the costs, including those incurred by Detimos – Gestão Imobiliária, SA in the course of the proceedings before the Board of Appeal of the Office for Harmonisation in the Internal Market (Trade Marks and Designs) (OHIM).

Frimodt Nielsen | Dehousse | Collins |

Delivered in open court in Luxembourg on 16 January 2014.

[Signatures]