JUDGMENT OF THE GENERAL COURT (Seventh Chamber)

17 December 2015 (*)

(State aid — Shipbuilding — Tax provisions applicable to certain agreements put in place for the financing and acquisition of vessels — Decision declaring the aid incompatible in part with the internal market and ordering its partial recovery — Actions for annulment — Individual concern — Admissibility — Advantage — Selectivity — Effect on trade between Member States — Adverse effect on competition — Obligation to state reasons)

In Joined Cases T‑515/13 and T‑719/13,

Kingdom of Spain, represented initially by N. Díaz Abad, and subsequently by M. Sampol Pucurull, Abogados del Estado,

applicant in Case T‑515/13,

Lico Leasing, SA, established in Madrid (Spain),

Pequeños y Medianos Astilleros Sociedad de Reconversión, SA, established in Madrid,

represented by M. Merola and A. Sánchez, lawyers,

applicants in Case T‑719/13,

v

European Commission, represented by V. Di Bucci, M. Afonso, É. Gippini Fournier and P. Němečková, acting as Agents,

defendant,

APPLICATION for annulment of Commission Decision 2014/200/EU of 27 July 2013 on the aid scheme SA.21233 C/11 (ex NN/11, ex CP 137/06) implemented by Spain — Tax scheme applicable to certain finance lease agreements also known as the Spanish Tax Lease System (OJ 2014 L 114, p. 1),

THE GENERAL COURT (Seventh Chamber),

composed of M. van der Woude (Rapporteur), President, I. Wiszniewska-Białecka and I. Ulloa Rubio, Judges,

Registrar: J. Palacio González, Principal Administrator,

having regard to the written procedure and further to the hearings on 9 and 10 June 2015,

gives the following

Judgment

Background to the dispute

I – Administrative procedure

1 The European Commission received, from May 2006, several complaints against what is known as ‘the Spanish Tax Lease System’ (‘the STL system’). In particular, two national federations of shipyards and one individual shipyard complained that the system enabled shipping companies to buy ships built by Spanish shipyards at a 20%-30% rebate (‘the rebate’), resulting in the loss of shipbuilding contracts for their members. On 13 July 2010, the shipbuilding associations of seven European countries signed a petition against the STL system. At least one shipping company supported those complaints.

2 Following numerous requests for information sent by the Commission to the Spanish authorities and two meetings between those parties, the Commission initiated the formal examination procedure under Article 108(2) TFEU, by Decision C(2011) 4494 final of 29 June 2011 (OJ 2011 C 276, p. 5) (‘the decision to initiate the procedure’).

II – Contested decision

3 On 17 July 2013, the Commission adopted Decision 2014/200/EU on the aid scheme SA.21233 C/11 (ex NN/11, ex CP 137/06) implemented by Spain — Tax scheme applicable to certain finance lease agreements also known as the Spanish Tax Lease System (OJ 2014 L 114, p. 1; ‘the contested decision’). By that decision, the Commission considered that certain tax measures constituting the STL system ‘constitute[d] State aid’ within the meaning of Article 107(1) TFEU, unlawfully put into effect by the Kingdom of Spain since 1 January 2002 in breach of Article 108(3) TFEU (Article 1 of the contested decision). Those measures were considered to be incompatible in part with the internal market (Article 2 of the contested decision). Recovery was ordered, on certain conditions, solely from the investors who had benefited from the advantages in question, without the possibility for those investors to transfer the burden of recovery to other persons (Article 4(1) of the contested decision).

A – Description of the STL system

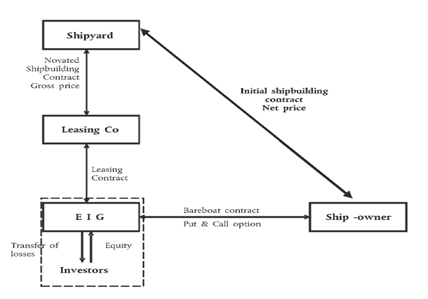

4 In recital 8 of the contested decision, the Commission stated that the STL system was used in transactions involving the building by shipyards (sellers) and the acquisition by maritime shipping companies (buyers) of sea-going vessels and the financing of those transactions by means of an ad hoc legal and financial structure.

5 The Commission explained that ‘the STL system [was] based on an ad hoc legal and financial structure organised by a bank and interposed between the shipping company and the shipyard …, a complex network of contracts between the different parties and the application of several Spanish tax measures’ (recital 9 of the contested decision).

6 The Commission also observed that ‘buyers [were] shipping companies from all over Europe and beyond’ and that ‘all but one of the transactions (a contract for EUR 6 148 969) [had] involved Spanish shipyards’ (recital 10 of the contested decision).

1. Legal and financial structure of the STL system

7 It is apparent from recitals 9 and 10 of the decision to initiate the procedure, to which, in essence, recital 14 of the contested decision refers, that the STL system involves, for each ship construction order, a number of players, namely a shipping company, a shipyard, a bank, a leasing company, an Economic Interest Grouping formed by the bank (‘the EIG’) and investors who purchase shares in the EIG.

8 The Commission provided the following explanation in recital 12 of the contested decision:

‘The STL structure is a tax planning scheme generally organised by a bank in order to generate tax benefits for investors in a tax transparent EIG and transfer part of these tax benefits to the shipping company in the form of a rebate on the price of the vessel. The rest of the benefits are kept by the investors in the EIG as remuneration for their investment. In addition to the EIG, an STL operation also involves other intermediaries, such as a bank and a leasing company (see chart below).’

9 In the context of the STL, the players referred to in paragraph 7 above sign a number of contracts, which will be explained below. The interested parties also sign a framework agreement which sets out in detail the organisation and functioning of the STL (recital 9(h) of the decision to initiate the procedure).

a) Initial shipbuilding contract

10 The shipping company which intends to purchase a vessel and to take advantage of the rebate agrees with a shipyard on the ship to be built and on a purchase price which incorporates the rebate (‘the net price’). The initial shipbuilding contract provides for payment of the net price to the shipyard by regular instalments. The shipyard asks a bank to organise the STL structure and arrangements (recital 9(a) of the decision to initiate the procedure).

b) New shipbuilding contract (novation)

11 The bank brings in a leasing company, which, through a novation agreement, takes the place of the shipping company and enters into a new contract with the shipyard for the purchase of a vessel for a price not including the rebate (‘the gross price’). A novation allows one obligation to be replaced by another obligation or a party to the contract to be replaced by another party. This new contract provides for payment to the shipyard of a regular instalment in addition to the instalments provided for in the initial shipbuilding contract, which corresponds to the rebate (the difference between the gross and the net prices) (recital 9(c) of the decision to initiate the procedure).

c) Formation of an EIG by the bank and call for investors

12 It is apparent from recital 9(b) of the decision to initiate the procedure that the bank ‘sets up an [EIG] and sells shares to interested investors’, that ‘typically, these investors are big Spanish taxpayers who invest in the EIG with a view to reducing their tax base’ and that, ‘in general, these investors do not carry out any shipping activities’. The Commission stated, in recital 28 of the contested decision, that, ‘since the EIGs involved in STL operations are regarded as an investment vehicle by their members — rather than as a way of carrying out an activity jointly — this Decision refers to them as investors’.

d) Leasing contract

13 The leasing company referred to in paragraph 11 above leases the vessel to the EIG, with an option to buy, for a period of three or four years on the basis of the gross price. The EIG commits in advance to exercise the option to buy the vessel at the end of that period. The contract provides for payment of very high lease instalments to the leasing company, which gives rise to significant losses for the EIGs. Conversely, the option exercise price is small (recital 9(d) of the decision to initiate the procedure). In practice, the EIG leases the vessel under the leasing contract from the date on which its construction starts (recital 10 of the decision to initiate the procedure).

e) Bareboat charter with option to purchase

14 It follows from recital 9(e) of the decision to initiate the procedure that the EIG, in turn, leases the vessel ‘over a short period’ to the shipping company under a bareboat charter. A bareboat charter is an arrangement for the chartering of a ship which includes neither crew nor provisions, for which the charterer is responsible. The shipping company undertakes at the outset to buy the vessel from the EIG at the end of the charter period, on the basis of the net price. Unlike the leasing agreement described in paragraph 13 above, the price of the lease payments provided for in the bareboat charter is low. Conversely, the price to exercise the purchase option is high. In practice, the bareboat charter is executed once construction of the vessel has been completed. The date for the exercise of the purchase option is set for ‘a few weeks’ after the date of purchase of the vessel by the EIG from the leasing company, referred to in paragraph 13 above (recital 10 of the decision to initiate the procedure).

15 It is therefore apparent from the legal and financial structure of the STL system, as described in the decision to initiate the procedure and the contested decision, that the bank interposes, in the context of the sale of a vessel by a shipyard to a shipping company, two intermediaries, namely a leasing company and an EIG. The EIG undertakes, in the context of a leasing agreement, to purchase the vessel at a gross price, which is passed on to the shipping company by the leasing company. Conversely, when it resells the vessel to the shipping company, in the context of a bareboat contract with an option to purchase, it receives only the net price, which takes into account the rebate granted to the shipping company at the outset.

2. Tax structure of the STL

16 According to the Commission, ‘the purpose of the STL scheme … is first to generate the benefits of certain tax measures in favour of the EIG and the investors participating in it, which will then pass on part of those benefits to the shipping company that acquires a new vessel’ (recital 15 of the contested decision).

17 It is apparent from recitals 15 to 20 of the contested decision and recitals 12 to 19 of the decision to initiate the procedure, to which recital 18 of the contested decision refers, that ‘the EIG collects the tax benefits in two stages’ (recital 16 of the contested decision).

18 In fact, ‘in the first stage, early [measure 2, examined in paragraph 25 below] and accelerated depreciation [measure 1, examined in paragraph 24 below] of the leased vessel is applied within the “normal” corporate income tax system[, which] generates heavy tax losses for the EIG[;] because of the EIG’s tax transparency [measure 3, examined in paragraph 27 below], these tax losses are deductible from the investors’ own revenues pro rata to their shares in the EIG’ (recital 16 of the contested decision).

19 The Commission explained, in recital 17 of the contested decision, that, ‘in normal circumstances, the tax savings made by this early and accelerated depreciation of the cost of the vessel should be offset later on by increased tax payments either when the vessel is completely depreciated and no more depreciation costs can be deducted or when the vessel is sold and a capital gain results from the sale’. However, the tax savings in question were not offset in the context of the STL system.

20 In fact, ‘in the second stage, the tax savings resulting from the initial losses transferred to the investors are then safeguarded as a result of the EIG’s switchover to the tonnage tax system of income taxation [which allows] full exemption of the capital gains resulting from the sale of the vessel … to the shipping company [measures 4 and 5, examined in paragraphs 27 to 29 below]’. This sale takes place when the vessel has been depreciated by the EIG and shortly after the switch to the special tonnage tax system (recital 18 of the contested decision).

21 According to the Commission, ‘the combined effect of the tax measures used in the STL enables the EIG and its investors to achieve a tax gain of approximately 30% of the initial gross price of the vessel[;] part of this tax gain — initially collected by the EIG/its investors — is kept by the investors (10%-15%) and part of it is passed on to the shipping company (85%-90%), which in the end becomes the owner of the vessel, with a 20% to 30% reduction in the initial gross price of the vessel’ (recital 19 of the contested decision).

22 It is apparent from recital 20 of the contested decision that ‘STL operations combine different individual — yet interrelated — tax measures in order to generate a tax benefit’. Those measures are provided for in a number of provisions of Real Decreto Legislativo 4/2004, por el que se aprueba el texto refundido de la Ley del Impuesto sobre Sociedades (Royal Legislative Decree 4/2004 approving the consolidated version of the Law on Corporation Tax), of 5 March 2004 (BOE No 61, of 11 March 2004, p. 10951, ‘the TRLIS’) and of Real Decreto 1777/2004, por el que se aprueba el Reglamento del Impuesto sobre Sociedades (Royal Decree 1777/2004 approving the Regulation on Corporation Tax), of 30 July 2004 (BOE No 189, of 6 August 2004, p. 37072, ‘the RIS’).

23 The process involves the following five measures, described in recitals 21 to 42 of the contested decision.

a) Measure 1: Accelerated depreciation of leased assets (Article 115(6) TRLIS)

24 Article 115(6) TRLIS allows accelerated depreciation of a leased asset by making the payments under a leasing contract relating to that asset deductible (recitals 21 to 23 of the contested decision).

b) Measure 2: Discretionary application of early depreciation of leased assets (Article 48(4) and Article 115(11) TRLIS and Article 49 RIS)

25 Under Article 115(6) TRLIS, the accelerated depreciation of the leased asset starts on the date on which the asset becomes operational, that is to say, not before the asset is delivered to and starts being used by the lessee. However, pursuant to Article 115(11) TRLIS, the Ministry of Economic Affairs may, upon formal request by the lessee, determine an earlier starting date for depreciation. Article 115(11) TRLIS imposes two general conditions for early depreciation. The specific conditions applicable to EIGs are set out in Article 48(4) TRLIS. The details of the authorisation procedure provided for in Article 115(11) TRLIS are set out in Article 49 RIS (recitals 24 to 26 of the contested decision).

c) Measure 3: EIGs

26 The Commission observed, in recital 27 of the contested decision, that ‘Spanish EIGs have a separate legal personality from that of their members’ and that, ‘as a result, EIGs can file an application both for the early depreciation measure and for the alternative tonnage taxation scheme provided for by Articles 124 to 128 TRLIS … if they meet the eligibility requirements under Spanish law, even if none of their members is a shipping company’. The Commission points out in that regard, in recital 28 of the contested decision, that ‘however, from a tax perspective, EIGs are transparent with respect to their Spanish resident shareholders’ and that ‘in other words, for tax purposes, profits (or losses) made by EIGs are directly attributed to their Spanish resident members on a pro rata basis’. The Commission adds, in recital 29 of the contested decision, that ‘EIGs’ tax transparency means that the substantial losses incurred by the EIG through early and accelerated depreciation can be passed on directly to the investors, who can offset these losses against profits of their own and reduce the tax due’.

d) Measure 4: Tonnage tax system (Articles 124 to 128 TRLIS)

27 The Commission observed, in recitals 30 and 31 of the contested decision, that the tonnage tax system provided for in Articles 124 to 128 TRLIS had been authorised in 2002 as State aid compatible with the internal market on the basis of the Community Guidelines on State aid to maritime transport of 5 July 1997 (OJ 1997 C 205, p. 5), amended on 17 January 2004 (OJ 2004 C 13, p. 3) (‘the Maritime Guidelines’) (Commission Decision C(2002) 582 final of 27 February 2002 concerning State aid N 736/2001 implemented by Spain — Scheme for the tonnage based taxation of shipping companies (OJ 2004 C 38, p. 4)).

28 It follows from recitals 30, 37 and 38 of the contested decision that, on the basis of the tonnage tax system, undertakings entered in one of the registers of shipping companies which have obtained authorisation from the tax administration to that end are taxed not on the basis of their profits and losses but on the basis of tonnage. That means that the proceeds of the sale of a vessel previously bought new by an undertaking already benefiting from the tonnage tax system are not subject to tax. However, there is an exception to that rule. On the basis of a special procedure provided for in Article 125(2) TRLIS, the capital gains realised from the sale of a vessel already acquired at the time of entry into the tonnage tax system or of a ‘used’ vessel acquired when the undertaking already benefits from the special regime, are taxed at the time of sale. Thus, ‘under normal application of the Spanish TT system, as approved by the Commission, potential capital gains are taxed on entry into the TT system and it is assumed that the taxation of capital gains, even though it is delayed, takes place later on when the vessel is sold or dismantled’ (recital 39 of the contested decision).

e) Measure 5: Article 50(3) RIS

29 The Commission observed, in recital 41 of the contested decision, that, ‘by way of exception from the rule set out in Article 125(2) TRLIS [see paragraph 28 above], Article 50(3) RIS states that when vessels are acquired through a call option as part of a leasing contract previously approved by the tax authorities, those vessels are deemed to be new — not used’ within the meaning of Article 125(2) TRLIS, without taking into consideration whether they have already been depreciated. On that basis, any capital gains realised from that sale are not taxed under the special procedure laid down in Article 125(2) TRLIS.

30 According to the information available to the Commission, ‘this exception was only applied to specific leasing contracts approved by the tax authorities in the context of applications for early depreciation pursuant to Article 115(11) TRLIS [measure 2, see paragraph 25 above], [that is to say] in relation to leased newly built sea-going vessels acquired through STL operations, and — with one exception — from Spanish shipyards’ (recital 41 of the contested decision).

31 Therefore, according to the Commission, ‘in the case of the authorised STL transactions, … the EIGs can … join the TT system without settling the hidden tax liability resulting from the early and accelerated depreciation either upon entry into the TT system or subsequently when the vessel is sold or dismantled’ (recital 40 of the contested decision).

32 It therefore follows from the fiscal structure of the STL, as described in recitals 15 to 42 of the contested decision, that measures 1 and 2 allow first of all the accelerated and early depreciation of the vessel from the start of its construction, so that losses are generated for the EIGs. Because of the fiscal transparency of the EIGs (measure 3), those losses are attributed for tax purposes to the investors, which enables them to reduce their taxable basis in the context of their activities. Measures 4 and 5 have the effect that the capital gains realised on the sale of the vessel by the EIG to the shipping company are not subject to tax, so that the investors are able to retain the benefit of the tax losses. However, as stated in paragraph 15 above, that sale is made on the basis of the net price (including the rebate granted to the shipping company) instead of the gross price (passed on to the shipyard).

B – Assessment by the Commission

1. Examination of the STL as a scheme/examination of the various measures

33 In recitals 113 to 122 of the contested decision (Section 5.2), the Commission defined the scope of its assessment of the STL.

34 According to the Commission, ‘the fact that the STL system is composed of various measures that are not all enshrined in the Spanish tax legislation is not sufficient to prevent the Commission from describing and assessing it as a system[;] indeed, … [it] considers that the different tax measures used in the STL operations were linked together de jure or de facto’ (recital 116 of the contested decision). For those reasons, the Commission ‘considers that it is necessary to describe the [STL] as a system of connected tax measures and to assess their effects in their reciprocal context, taking into account, in particular, the de facto relationships introduced — or approved — by the State’ (recital 119 of the contested decision).

35 The Commission stated that, ‘in any case, [it did] not rely exclusively on a global approach’ and that, ‘in parallel to a global approach, [it had] also analysed the individual measures that [made] up the STL’. The Commission considered that ‘the two approaches [were] complementary and [led] to consistent conclusions’. It observed that ‘individual assessment [was] necessary to determine which part of the economic advantages generated by the STL system result[ed] from general measures and which from selective measures’ and that ‘individual assessment also allow[ed] [it] to determine, where necessary, which part of the aid [was] compatible with the internal market and which part should be recovered’ (recital 120 of the contested decision).

36 The Commission also observed that ‘economic operators [were] free to structure their asset financing operations as they wish[ed] and use for that purpose the general tax measures which they consider[ed] the most suitable’. However, according to the Commission, ‘inasmuch as these operations entail[ed] the application of selective tax measures, which [were] subject to State aid control, the undertakings involved in these transactions [were] potential recipients of State aid[;] on the one hand, the fact that several sectors or categories of undertakings [were] identified as potential recipients [was] not an indication that the STL system [was] a general measure[;] on the other hand, the fact that the system [was] used to finance the acquisition, bareboat chartering and resale of sea-going vessels [could] be seen as a clear indication that the measure [was] selective from a sectoral point of view’ (recital 122 of the contested decision).

2. Existence of aid within the meaning of Article 107(1) TFEU

a) Undertakings within the meaning of Article 107 TFEU

37 The Commission observed, in recital 126 of the contested decision, that all parties involved in STL operations were undertakings within the meaning of Article 107(1) TFEU, since their activities consisted in offering goods and services in a market. As regards, more precisely, the EIGs, they ‘charter[ed] out and [sold] vessels’. As regards the investors, they ‘offer[ed] goods and services on a wide range of markets, except if they [were] individuals not exercising any economic activity, in which case they [were] not covered by this Decision’.

b) Existence of a selective advantage

38 In recitals 127 to 163 of the contested decision (Section 5.3.2), the Commission examined whether or not there was a selective advantage.

39 As regards measure 1 (accelerated depreciation), the Commission considered that ‘as such [it did] not confer a selective advantage on the EIGs in STL operations’ (recital 131 of the contested decision). In fact, the advantage conferred by that measure was applicable, without limitation, to all assets, including those constructed in other Member States, and to all undertakings subject to income tax in Spain. The Commission observed that there was no indication that recipients of the measure were de facto concentrated in certain sectors or types of production. Last, the conditions of application of the measure were clear, objective and neutral and their application by the tax administration did not require prior authorisation (recitals 128 to 130 of the contested decision).

40 As regards measure 2 (discretionary application of early depreciation), the Commission observed that that possibility conferred an economic advantage (recital 132 of the contested decision) and that it was an exception to the general rule and subject to discretionary authorisation by the Spanish authorities. According to the Commission, the criteria set out in Article 115(11) TRLIS were vague and required interpretation from the tax administration. In addition, the Kingdom of Spain had not convincingly explained why all the conditions imposed by Article 48(4) TRLIS and Article 49 RIS were necessary to avoid abuses. Nor had the Kingdom of Spain demonstrated why prior authorisation was necessary (recital 133 of the contested decision). Furthermore, no evidence was provided establishing that authorisations had been granted in circumstances other than ‘in the case of acquisitions of vessels that had switched from the normal corporate taxation regime to the TT system and the subsequent transfer of ownership of the vessel to the shipping company through the exercise of an option in the context of a bareboat charter’ (recital 134 of the contested decision). The Commission observed that the requests submitted for the benefit of that measure described in detail the whole STL organisation and provided all the relevant contracts (recital 135 of the contested decision). The Commission also considered that the authorisation procedure, in particular Article 49 RIS, conferred important discretionary powers on the tax administration. In particular, the administration was allowed to require any additional information it might deem relevant for the assessment (recital 136 of the contested decision). In those circumstances, the Commission concluded that the discretionary application of early depreciation ‘confer[red] a selective advantage on the EIGs involved in STL operations and on their investors’ (recital 139 of the contested decision).

41 As regards measure 3 (EIG), the Commission considered that ‘the tax transparent status of EIGs enshrined in Articles 48 and 49 TRLIS merely enable[d] different operators to join and finance any investment or carry out any economic activity’ and that, ‘as a consequence, that measure [did] not confer any selective advantage on the EIGs or their members’ (recital 140 of the contested decision).

42 As regards measure 4 (tonnage tax system), the Commission observed that it allowed ‘the deferral … of the settlement of hidden tax liabilities’, which conferred ‘an additional selective economic advantage on the companies that switch to the TT system, as against those that stay[ed] within the general tax system’ (recital 143 of the contested decision). The tonnage tax system, as authorised by the Commission (see paragraph 27 above), did not extend to the tax treatment of revenues obtained from bareboat chartering and the resale of vessels, but only to the revenues obtained from shipping activities. The application of the tonnage tax system to revenues obtained from bareboat chartering would therefore constitute new aid and not existing aid that would have been approved in advance by the Commission (recital 144 of the contested decision, which refers to Section 5.4 of the contested decision).

43 As regards measure 5 (Article 50(3) RIS), the Commission observed that ‘the economic advantage conferred by [that provision was] selective because it [was] not available to all assets[;] it [was] not even available to all vessels subject to the TT scheme and to Article 125(2) TRLIS[;] in fact, this advantage [was] only available on condition that the vessel [was] acquired through a financial leasing contract previously authorised by the tax administration [under Article 115(11) TRLIS (measure 2)]’. However, ‘these authorisations were granted in the context of substantial discretionary powers exercised by the tax administration and in practice only in relation to newly built sea-going vessels’ (recital 146 of the contested decision). According to the Commission, ‘this additional selective advantage — be it by reference to the general tax scheme or even by reference to the normal application of the alternative TT system and Article 125(2) TRLIS as authorised by the Commission — cannot be justified by the nature and general scheme of the Spanish tax system’ (recital 148 of the contested decision). The Commission concluded that measure 5 ‘confer[red] a selective advantage on undertakings that acquire[d] vessels through financial leasing contracts previously authorised by the tax administration and, in particular, on the EIGs or their investors involved in STL operations’ (recital 154 of the contested decision).

44 As regards the STL as a whole, and the identification of the beneficiaries, the Commission first of all stated, in recital 155 of the contested decision, that ‘the amount of the economic advantage resulting from the STL … correspond[ed] to the advantage that the EIG would not have achieved in the same financing operation by the sole application of general measures’. The Commission explained that, ‘in practice, this advantage correspond[ed] to the sum of the advantages reaped by the EIG by applying the abovementioned selective measures, namely: the interest saved on the amounts of tax payment deferred by virtue of early depreciation (Articles 115(11) and 48(4) TRLIS and Article 49 RIS); the amount of tax avoided or interest saved on tax deferred by virtue of the TT scheme (Article 128 TRLIS), given that the EIG was not eligible for the TT scheme; [and] the amount of tax avoided on the capital gain made on the sale of the vessel by virtue of Article 50(3) RIS’.

45 The Commission provided the following explanation, in recital 156 of the contested decision:

‘Looking at the STL as a whole, the advantage is selective because it was subject to the discretionary powers conferred on the tax administration by the compulsory prior authorisation procedure and by the imprecise wording of the conditions applicable to early depreciation. Since other measures applicable only to maritime transport activities eligible under the Maritime Guidelines — in particular Article 50(3) TRLIS — are dependent on that prior authorisation, the whole STL system is selective. As a result, the tax administration would only authorise STL operations to finance sea-going vessels (sectoral selectivity). As confirmed by the statistics provided by [the Kingdom of] Spain, all the 273 STL operations organised until June 2010 concern sea-going vessels.’

46 The Commission added, in recital 157 of the contested decision, that ‘in that respect, the fact that all shipping companies, including companies established in other Member States, potentially have access to STL financing operations [did] not alter the conclusion that the scheme favours certain activities, namely the acquisition of sea-going vessels through leasing contracts, in particular with a view to their bareboat chartering and subsequent resale’.

47 Although the Commission stated that ‘all but one of the vessels admitted to STL [had been] built in Spanish shipyards’, it did not consider that a selective advantage within the meaning of Article 107(1) TFEU was conferred on those shipyards. In that regard, the Commission noted that there was no ‘evidence that applications related to the acquisition of non-Spanish vessels were rejected’ and that, ‘by a binding notice in response to a question by a prospective investor, dated 1 December 2008, the Spanish tax administration expressly confirmed that STL applie[d] to ships built in other Member States of the [European Union]’ (recitals 159 and 160 of the contested decision).

48 The Commission considered that ‘the advantage accrue[d] to the EIG and, by transparency, to its investors[;] indeed, the EIG [was] the legal entity that applie[d] all the tax measures and, where applicable, file[d] requests for authorisations with the tax administration[;] for instance, it [was] not disputed that requests for the application of early depreciation or TT [had been] filed on behalf of the EIG[;] from a tax perspective, the EIG [was] a tax-transparent entity and its taxable revenues or deductible expenses [were] automatically transferred to the investors’ (recital 161 of the contested decision).

49 The Commission also pointed out, in recital 162 of the contested decision, that ‘in an STL operation, in economic terms, a substantial part of the tax advantage collected by the EIG is transferred to the shipping company through a price rebate’. The Commission stated, however, that ‘the question of the imputability to the State of this advantage [would] be discussed in the next section’.

50 Last, the Commission observed that ‘whereas other participants in STL transactions such as shipyards, leasing companies and other intermediaries benefit[ed] from an indirect effect of that advantage, [it] consider[ed] that the advantage initially collected by the EIG and its investors [was] not transferred to them’ (recital 163 of the contested decision).

c) Transfer of State resources and imputability to the State

51 According to the Commission, ‘in the context of STL operations, the State initially transfers its resources to the EIG by financing the selective advantages[;] by way of tax transparency, the EIG then transfers the State resources to its investors’ (recital 166 of the contested decision).

52 As regards imputability, the Commission concluded that the selective advantages were ‘clearly imputable to the Spanish State since they [were] of benefit to the EIGs and their investors’. However, ‘this [was] not the case with the advantages enjoyed by the shipping companies and a fortiori the indirect advantages flowing to the shipyards and the intermediaries’. Indeed, ‘the applicable rules [did] not oblige the EIGs to transfer part of the tax advantage to the shipping companies and, even less so, to the shipyards or to the intermediaries’ (recitals 169 and 170 of the contested decision).

d) Distortion of competition and effect on trade

53 According to the Commission, ‘this advantage threatens to distort competition and to affect trade between Member States[;] when aid granted by a Member State strengthens the position of an undertaking compared with other undertakings competing in intra-EU trade, the latter [undertakings] must be regarded as affected by that aid[;] it is sufficient that the recipient of the aid competes with other undertakings on markets open to competition and to trade between Member States’ (recital 171 of the contested decision).

54 The Commission made the following observation in recital 172 of the contested decision: ‘In the case at hand, the investors, [that is to say] the members of the EIGs, are active in different sectors of the economy, in particular in sectors open to intra-EU trade. In addition, via the operations benefiting from STL they are active through the EIGs in the markets for bareboat chartering and the acquisition and sale of sea-going vessels, which are open to intra-EU trade. The advantages flowing from the STL strengthen their position in their respective markets, thereby distorting or threatening to distort competition’. The Commission concluded, in recital 173 of the contested decision, that ‘the economic advantage received by the EIGs and their investors benefiting from the measures under scrutiny [was] therefore liable to affect trade between the Member States and distort competition in the internal market’.

3. Compatibility with the internal market

55 The Commission considered, in recitals 194 to 199 of the contested decision, that neither its decision on the tonnage tax scheme (see paragraph 27 above) nor the Maritime Guidelines applied to the activities of the EIGs, which were ‘financial intermediaries’ (recital 197 of the contested decision).

56 However, the Commission observed that ‘the EIGs involved in STL operations and their investors act[ed] as intermediaries which channel[led] to other recipients (shipping companies) an advantage that pursue[d] an objective of common interest’ (recital 200 of the contested decision) and that, accordingly, ‘the aid retained by the EIG or its investors would be found compatible in the same proportion’ (recital 201 of the contested decision).

57 The Commission observed that ‘the shipping companies [did] not benefit from State aid within the meaning of Article 107(1) TFEU’. However, it made clear that, ‘in order to identify the amount of compatible aid at the level of the EIGs — as intermediaries channelling to shipping companies an advantage that pursues an objective of common interest — [it] consider[ed] that the Maritime Guidelines should be applied mutatis mutandis to the advantage transferred by the EIG to the shipping company in order to determine: (1) the amount of the aid initially received by the EIG and transferred to the shipping company that would have been compatible if the amount transferred constituted State aid to the shipping company; (2) the proportion of that compatible advantage in the total advantage transferred to the shipping company; and (3) the amount of aid that should be deemed compatible as remuneration of the EIGs for their intermediation’ (recital 203 of the contested decision).

4. Recovery

a) General principles of EU law

58 The Commission examined, in recitals 211 to 276 of the contested decision and in accordance with Article 14 of Council Regulation (EC) No 659/1999 of 22 March 1999 laying down detailed rules for the application of Article [108 TFEU] (OJ 1999 L 83, p. 1), whether recovery of the aid would be contrary to a general principle of EU law. In that regard, the Commission considered that, while the principles of equal treatment and protection of legitimate expectations did not stand in the way of recovery of the aid (recitals 213 to 245 of the contested decision), respect for the principle of legal certainty precluded ‘the recovery of aid resulting from STL operations in respect of which the aid was granted between the entry into force of the STL in 2002 and 30 April 2007’, the date of publication in the Official Journal of the European Union of Commission Decision 2007/256/EC of 20 December 2006 on the aid scheme implemented by France under Article 39 CA of the General Tax Code — State aid C 46/2004 (ex NN 65/2004) (OJ 2007 L 112, p. 41) (recitals 246 to 262 of the contested decision).

b) Determination of the amounts to be recovered

59 The Commission set out, in recitals 263 to 269 of the contested decision, a method for determining the amounts of incompatible aid to be recovered, based on four steps, namely, first, calculation of the total tax advantage generated by the operation; second, calculation of the tax advantage generated by the general tax measures (measures 1 and 3) applied to the operation (that should be deducted); third, calculation of the tax advantage equivalent to State aid; and, fourth, calculation of amount of compatible aid, in accordance with the principles set out in recitals 202 to 210 of the contested decision.

c) Contractual clauses

60 Last, the Commission established, in recitals 270 to 276 of the contested decision, the existence of certain clauses in contracts between the investors, the shipping companies and the shipyards, under which the shipyards would be required to compensate the other parties if the expected tax advantages could not be obtained. In that regard, the Commission recalled that the main objective pursued in recovering State aid was to eliminate the distortion of competition caused by the competitive advantage afforded by the unlawful aid and thus to restore the situation prior to payment of the aid. In recital 273 of the contested decision, the Commission stated that, ‘in order to achieve that result, [it] must have the power to order that recovery takes place from the actual recipients, so that [recovery] can fulfil the function of re-establishing the competitive situation in the market(s) where the distortion has occurred’. The Commission pointed out that that objective may be frustrated if the actual recipients of the aid could alter the impact of recovery decisions by means of contractual clauses. It follows, according to the Commission, that ‘contractual clauses sheltering the recipients of the aid from recovery of illegal and incompatible aid, by transferring the legal and economic risks of such recovery to other persons, are contrary to the very essence of the system of State aid control established by the Treaty’ and that ‘therefore, private parties cannot depart from [those rules] by contractual stipulations’ (recital 275 of the contested decision).

C – Operative part of the contested decision

61 The operative part of the contested decision is worded as follows:

‘Article 1

The measures resulting from Article 115(11) TRLIS (early depreciation of leased assets), from the application of the tonnage tax scheme to non-eligible undertakings, vessels or activities and from Article 50(3) RIS constitute State aid to the EIGs and their investors, unlawfully put into effect by [the Kingdom of] Spain since 1 January 2002 in breach of Article 108(3) [TFEU].

Article 2

The State aid measures referred to in Article 1 are incompatible with the internal market, except to the extent that the aid corresponds to a remuneration in conformity with the market for the intermediation of financial investors and that it is channelled to maritime transport companies eligible under the Maritime Guidelines in compliance with the conditions imposed in those Guidelines.

Article 3

[The Kingdom of] Spain shall put an end to the aid scheme referred to in Article 1 to the extent that it is incompatible with the common market.

Article 4

1. [The Kingdom of] Spain shall recover the incompatible aid granted under the scheme referred to in Article 1 from the EIG investors that have benefited from it, without the possibility for such recipients to transfer the burden of recovery to other persons. However, no recovery shall take place in respect of aid granted as part of financing operations in respect of which the competent national authorities have undertaken to grant the benefit of the measures by a legally binding act adopted before 30 April 2007.

…

Article 5

1. Recovery of the aid granted under the scheme referred to in Article 1 shall be immediate and effective.

2. [The Kingdom of] Spain shall ensure that this Decision is implemented within four months of the date of its notification.

Article 6

1. Within two months of notification of this Decision, [the Kingdom of] Spain shall submit the following information:

…

2. [The Kingdom of] Spain shall keep the Commission informed of the progress of the national measures taken to implement this Decision until recovery of the aid granted under the scheme referred to in Article 1 has been completed.

…’

Procedure and forms of order sought

62 By application lodged at the Court Registry on 25 September 2013, the Kingdom of Spain brought an action, registered as Case T‑515/13.

63 By application lodged at the Court Registry on 30 December 2013, Lico Leasing, SA (‘Lico’) and Pequeños y Medianos Astilleros Sociedad de Reconversión, SA (‘PYMAR’) brought an action, registered as Case T‑719/13.

64 In addition, other actions were brought by other applicants against the contested decision.

65 On 26 May 2014, the Court asked the Kingdom of Spain and the Commission whether it was appropriate to stay proceedings in Case T‑515/13, pursuant to Article 77(d) of the Rules of Procedure of the General Court of 2 May 1991, pending the close of the written stage of the proceedings in the other cases brought before the Court against the contested decision referred to in paragraphs 63 and 64 above. In its observations, the Kingdom of Spain objected to such a stay. The Commission did not raise any objections.

66 By order of 17 July 2014, the Court (Seventh Chamber) dismissed an application by the European Community Shipowners’ Associations to intervene in Case T‑719/13 in support of the form of order sought by the Commission.

67 On 17 February 2015, in the context of measures of organisation of procedure in Case T‑719/13, the Court put a question to Lico and PYMAR and asked them to produce certain documents. Lico and PYMAR answered the question and lodged the requested documents within the prescribed period.

68 On 26 February 2015, on a proposal from the Judge-Rapporteur, the Court (Seventh Chamber) decided to open the oral phase of the procedure in Case T‑515/13.

69 On 3 March 2015, in the context of measures of organisation of procedure in Case T‑515/13, the Court put two questions to the parties, to be answered orally at the hearing.

70 On 23 April 2015, on a proposal from the Judge-Rapporteur, the Court (Seventh Chamber) decided to open the oral phase of the procedure in Case T‑719/13.

71 On 28 April 2015, in the context of measures of organisation of procedure in Cases T‑515/13 and T‑719/13, the Court put a written question to the parties, concerning the inferences to be drawn in these cases from the judgments of 7 November 2014 in Autogrill España v Commission (T‑219/10, ECR, EU:T:2014:939) and Banco Santander and Santusa v Commission (T‑399/11, ECR, EU:T:2014:938), in particular as regards the analysis of selectivity made in the contested decision. The parties in both cases answered the question within the prescribed period.

72 The parties in Cases T‑515/13 and T‑719/13 presented oral argument and answered the questions put to them by the Court at the hearings on 9 and 10 June 2015 respectively.

73 At the hearings in Cases T‑515/13 and T‑719/13, the parties were asked by the Court to comment on whether the proceedings in those cases should be stayed, pursuant to Article 77(d) of the Rules of Procedure of 2 May 1991, pending delivery of the decision of the Court of Justice disposing of the proceedings in Case C‑20/15 P Commission v Autogrill España and in Case C‑21/05 P Commission v Banco Santander and Santusa. Although the parties did not object to such a stay of proceedings, they observed that it was not appropriate and that the Court could adjudicate in the context of the present cases on the basis of the existing case-law, without awaiting the decision of the Court of Justice.

74 By orders of 6 October 2015, the Court (Seventh Chamber) reopened the oral phase of the procedure in Cases T‑515/13 and T‑719/13 in order to ask the parties to comment on the possible joinder of the two cases for the purposes of the final judgment. The parties submitted their observations within the prescribed period.

75 By order adopted today, the President of the Seventh Chamber of the Court joined Cases T‑515/13 and T‑719/13 for the purposes of the final judgment, in application of Article 68 of the Rules of Procedure of the General Court.

76 In Case T‑515/13, the Kingdom of Spain claims that the Court should:

– annul the contested decision;

– order the Commission to pay the costs.

77 In Case T‑515/13, the Commission contends that the Court should:

– dismiss the action;

– order the Kingdom of Spain to pay the costs.

78 In Case T‑719/13, Lico and PYMAR claim that the Court should:

– annul the contested decision on the ground that the STL system was incorrectly classified as a State aid scheme which favours the EIGs and their investors, and on the ground of defective reasoning;

– in the alternative, annul the order for recovery of the aid granted through the STL system, because it is contrary to the general principles of the EU legal order;

– in the further alternative, annul the order for recovery as regards the calculation of the amount of incompatible aid to be recovered in so far as it prevents the Kingdom of Spain from determining the formula for calculating that amount in accordance with the general principles applicable to the recovery of State aid;

– order the Commission to pay the costs.

79 In Case T‑719/13, the Commission contends that the Court should:

– dismiss the action;

– order Lico and PYMAR to pay the costs.

Law

I – Admissibility of the action in Case T‑719/13

80 It is apparent from the application in Case T‑719/13 that Lico is a financial institution which invested in a number of EIGs that participated in the STL system. It claims that it brought its action in its capacity as actual beneficiary of aid that must be recovered on the basis of the contested decision. PYMAR is a company which cooperates with small and medium shipyards in order to enable them to achieve their industrial objectives in an appropriate manner. In order to substantiate its capacity to bring an action before the Court, it observes that, as a result of the contested decision, investors refuse to continue to invest in the shipbuilding sector. Furthermore, in spite of the invalidity of the clauses which required the shipyards to compensate investors in the event that the tax advantages at issue were recovered (see paragraph 60 above), the investors are attempting to rely on those clauses in judicial proceedings at national level. Last, both Lico and PYMAR participated in the formal examination procedure leading to the adoption of the contested decision, which in their submission also shows that they have locus standi.

81 Although it did not formally raise a plea of inadmissibility, the Commission expressed reservations as to the locus standi of both Lico and PYMAR.

82 As regards Lico, the Commission maintained that no evidence had been adduced that it had been individually affected. The documents supplied did not show conclusively that that entity received State aid that must be recovered under the STL. In particular, Lico did not produce the administrative authorisations necessary for the application of early depreciation, although they constituted the ‘act conferring the first tax advantage’, the date of which is relevant for the purpose of determining whether the aid must be recovered or whether it is covered by the period in respect of which the Commission did not order recovery, in accordance with the principle of legal certainty. At the hearing, the Commission further submitted that Lico ought also to have adduced evidence that it had in fact obtained taxable profits during the tax years in question. Otherwise, the tax advantages resulting from the STL (losses that could reduce Lico’s taxable base in the context of its activities) did not add anything. However, the Commission stated at the hearing that it did not require Lico to supply a copy of the recovery orders, as the recovery procedure initiated by the Spanish authorities had not yet been completed on that date.

83 As regards PYMAR, the Commission observes that it did not benefit from the STL and that the supposed loss of opportunities cannot be regarded as flowing directly from the contested decision. In addition, PYMAR has no interest in bringing an action against the contested decision, since that decision is favourable to it.

84 The Court considers it appropriate to examine first of all the admissibility of the action as regards Lico.

85 Under the fourth paragraph of Article 263 TFEU, ‘any natural or legal person may, under the conditions laid down in the first and second paragraphs, institute proceedings against an act addressed to that person or which is of direct and individual concern to them, and against a regulatory act which is of direct concern to them and does not entail implementing measures’.

86 In the present case, the contested decision is addressed solely to the Kingdom of Spain. Thus, in accordance with the fourth paragraph of Article 263 TFEU, Lico is entitled to bring proceedings before the Court only if the contested decision is of direct and individual concern to it, as that decision entails implementing measures within the meaning of that provision (see, to that effect, judgment of 19 December 2013 in Telefónica v Commission, C‑274/12 P, ECR, EU:C:2013:852, paragraphs 35 and 36).

87 In accordance with settled case-law, the actual beneficiaries of individual aid granted under an aid scheme of which the Commission has ordered recovery are, by that fact, individually concerned within the meaning of the fourth paragraph of Article 263 TFEU (see judgment of 9 June 2011 in Comitato ‘Venezia vuole vivere’ and Others v Commission, C‑71/09 P, C‑73/09 P and C‑76/09 P, ECR, EU:C:2011:368, paragraph 53 and the case-law cited).

88 In the present case, the fact that the contested decision was of individual concern to Lico has been sufficiently demonstrated by the material produced before the Court. That material included copies of tax notifications from the tax administration stating that an investigation had been initiated in order to determine ‘the amount of aid to be recovered pursuant to the [contested] decision’ and, as required by the Commission in its defence, copies of the authorisations granting the benefit of early depreciation to the EIGs in which Lico had purchased shares. The Commission does not dispute that, by virtue of the principle of tax transparency, it is the members of those EIGs — and, accordingly, Lico — that benefited from the economic advantage authorised by the tax administration. It should be noted that all of those authorisations were granted after 30 April 2007, the date after which recovery is ordered in the contested decision, in accordance with Article 4(1) of that decision. The material in question therefore shows that Lico is an actual beneficiary of individual aid granted under the STL recovery of which the Commission ordered. It is thus unnecessary for Lico to adduce, in addition, evidence that it had actually made taxable profits during the tax years in question. As the Commission has recognised in its pleadings, authorisation of early depreciation is ‘the act conferring the first tax advantage’.

89 As to whether Lico is directly concerned, in so far as Article 4(1) of the contested decision obliges the Kingdom of Spain to take the measures necessary to recover the incompatible aid, from which Lico benefited, Lico must be held to be directly concerned by the contested decision (see, to that effect, judgment of 4 March 2009 in Associazione italiana del risparmio gestito and Fineco Asset Management v Commission, T‑445/05, ECR, EU:T:2009:50, paragraph 52 and the case-law cited).

90 As it has been established that the contested decision was of direct and individual concern to Lico and as its interest in bringing an action against that decision is not in doubt, the action in Case T‑719/13 must be declared admissible, without there being any need to determine whether PYMAR also satisfies the conditions of admissibility laid down in the fourth paragraph of Article 263 TFEU (see judgments of 24 March 1993 in CIRFS and Others v Commission, C‑313/90, ECR, EU:C:1993:111, paragraphs 30 and 31, and 26 October 1999 in Burrill and Noriega Guerra v Commission, T‑51/98, ECR-SC, EU:T:1999:271, paragraphs 19 to 21 and the case-law cited).

II – Substance

A – The scope of the first head of claim of Lico and PYMAR in Case T‑719/13

91 It should be observed that, by their first head of claim, supported by their first plea, Lico and PYMAR ask the Court to ‘annul the contested decision on the ground that the STL system was incorrectly classified as a State aid scheme which favours the EIGs and their investors, and on the ground of defective reasoning’.

92 However, it should be observed that Article 1 of the contested decision, which deals with the classification as State aid within the meaning of Article 107(1) TFEU, does not refer to the STL system as such, or classify it as ‘a State aid scheme’. That article is worded as follows: ‘The measures resulting from Article 115(11) TRLIS (early depreciation of leased assets), from the application of the tonnage tax scheme to non-eligible undertakings, vessels or activities and from Article 50(3) RIS constitute State aid to the EIGs and their investors, unlawfully put into effect by [the Kingdom of] Spain since 1 January 2002 in breach of Article 108(3) [TFEU]’. Article 4(1) of the contested decision, which orders recovery, refers to ‘the incompatible aid granted under the scheme referred to in Article 1’.

93 At the hearing, Lico and PYMAR explained that, by their first head of claim, they sought annulment of Article 1 in its entirety and that the three measures referred to in that provision had been mentioned in the application. The Commission claimed at the hearing that the first plea in the application did not refer to those three measures.

94 In that regard, it should be borne in mind that the operative part of an act is indissociably linked to the statement of reasons for it and when it has to be interpreted account must be taken of the reasons that led to its adoption (judgments of 15 May 1997 in TWD v Commission, C‑355/95 P, ECR, EU:C:1997:241, paragraph 21, and 29 April 2004 in Italy v Commission, C‑298/00 P, ECR, EU:C:2004:240, paragraph 97).

95 In the present case, as pointed out in paragraphs 33 to 35 above, the Commission deemed it necessary to describe the STL system, in recitals 116 to 122 of the contested decision, as a ‘system’ of tax measures that were linked together and to assess their effects in their reciprocal context, having regard, in particular, to the de facto relationships introduced by the State or with its approval. However, the Commission did not rely exclusively on a general approach. It also analysed individually the five measures that make up the STL, in order to ‘determine which part of the economic advantages generated by the STL system results from general measures and which from selective measures’ within the meaning of Article 107(1) TFEU. According to the Commission, ‘the two approaches are complementary and lead to consistent conclusions’ (recital 120 of the contested decision).

96 Following its individual examination of the measures going to make up the STL system, the Commission concluded, in recital 155 of the contested decision, that ‘the amount of the economic advantage resulting from the STL as a whole’ corresponded in ‘practice’ to ‘the sum of the advantages reaped by the EIG by applying the [three] abovementioned selective measures’, namely early depreciation (measure 2) and the application to the EIGs’ bareboat charter activities of the tonnage tax scheme (measure 4), as clarified by Article 50(3) RIS (measure 5).

97 It follows that the Commission concluded, in essence, that the STL system was a ‘system’ composed of five tax measures, three of which satisfied the conditions of Article 107(1) TFEU. That submission was also made by Lico and PYMAR in their application, where they referred to the wording of the contested decision.

98 Thus, when Lico and PYMAR ask the Court, in their first head of claim, supported by their first plea, to annul the contested decision ‘on the ground that the STL system was incorrectly classified as a State aid scheme’, they are necessarily also referring to the components of that system, referred to in Article 1 of the contested decision.

B – The pleas put forward in Cases T‑515/13 and T‑719/13

99 In support of its action in Case T‑515/13, the Kingdom of Spain puts forward, in essence, four pleas.

100 The first plea alleges infringement of Article 107(1) TFEU.

101 The second, third and fourth pleas are raised in the alternative and apply in the event that the Court should find the existence of unlawful State aid. They allege breach of several general principles of EU law in that the Commission ordered partial recovery of the aid alleged to have been granted. These pleas allege breach, respectively, of the principles of equal treatment, protection of legitimate expectations and legal certainty.

102 In support of their action in Case T‑719/13, Lico and PYMAR raise three pleas.

103 The first plea, put forward in support of their first head of claim, alleges infringement of Article 107(1) TFEU and Article 296 TFEU.

104 The second plea, put forward in the alternative, in support of their second head of claim, alleges breach of the principles of protection of legitimate expectations and legal certainty, as regards the obligation to recover the aid.

105 The third plea, also put forward in the alternative, in support of their third head of claim, disputes the method of calculating the aid defined by the Commission in the contested decision (see paragraph 59 above), which in their submission does not respect the general principles applicable to the recovery of aid. In particular, Lico and PYMAR submit that that calculation method, as described in the contested decision, might be interpreted as requiring investors to repay an amount corresponding to the total of the tax advantage which they received owing to the reduction of the tax, without taking account of the fact that they passed the main part of that advantage on to the shipping companies (see paragraph 21 above).

106 It is appropriate to examine together the first pleas put forward by the Kingdom of Spain, Lico and PYMAR in the two cases, relating to the classification of State aid within the meaning of Article 107(1) TFEU.

1. First plea, relating to the classification of State aid within the meaning of Article 107(1) TFEU

107 The Kingdom of Spain, Lico and PYMAR claim that the Commission infringed Article 107(1) TFEU, in so far as the conditions relating to selectivity, the risk of distortion of competition and the effect on trade are not satisfied. Although they do not formally claim that there has been an infringement of Article 296 TFEU on this point, Lico and PYMAR take issue in their application with the illogical and inconsistent reasoning as regards respect for those conditions. Furthermore, they allege that the Commission does not explain how the measure might have an effect on the designated markets and merely concludes that that effect is produced without demonstrating that it is. Without referring to Article 296 TFEU, the Kingdom of Spain also observes in the reply that the reasoning on which the contested decision is based is defective as regards proof that an advantage was conferred on the investors in the EIG and inconsistent as regards the test for distortion of competition.

108 In addition, the Kingdom of Spain, Lico and PYMAR observe that the conditions relating to selectivity, the risk of distortion of competition and the effect on trade should have been established solely with respect to the advantages obtained by the investors. In that regard, the Kingdom of Spain emphasises that the investors are the only entities referred to by the recovery order imposed by Article 4(1) of the contested decision. Thus, the only aid for the purposes of Article 107(1) TFEU identified by the Commission is the alleged advantage conferred on those investors. Lico and PYMAR further maintain that the selective advantage identified by the Commission consists essentially in a tax advantage. However, in application of the principle of tax transparency, the EIGs, as such, obtained no advantage, not even a tax advantage, because that advantage was transferred in full to their members. In answer to a question from the Court (see paragraph 71 above), the Kingdom of Spain pointed out that neither the status of EIG nor the principle of tax transparency had been called into question by the Commission in recital 140 of the contested decision.

109 In the context of Case T‑515/13, the Kingdom of Spain adds certain specific arguments.

110 First, contrary to the Commission’s assertions in recitals 116 to 119 of the contested decision, the STL is not a ‘system’ that exists as such in the applicable legislation. According to the Kingdom of Spain, what is known as the STL system is merely a set of legal acts carried out by taxpayers, who merely benefit, in the context of a tax optimisation strategy, from a combination of individual tax measures. The STL, as such, cannot therefore be imputed to the State.

111 Second, the Kingdom of Spain observes that early depreciation does not involve a reduction of tax and therefore does not confer a tax advantage.

112 Third, the Kingdom of Spain disputes the Commission’s finding that the tonnage tax system, as approved by the Commission (see paragraph 27 above), did not cover the activities of EIGs formed for the purposes of the STL system.

113 Last, the Kingdom of Spain claims that Article 50(3) RIS does not constitute an exception to that system, as approved.

114 The Court considers it appropriate to examine first of all the arguments common to both cases, mentioned in paragraphs 107 and 108 above, concerning the Commission’s analysis in relation to selectivity, the risk of distortion of competition and the effect on trade between Member States. In the context of that examination, it is appropriate, as the Kingdom of Spain, Lico and PYMAR suggest, to identify at the outset the beneficiaries of the economic advantages, within the meaning of Article 107(1) TFEU, arising from the measures at issue.

a) Identification of the beneficiaries of the economic advantages

115 The Commission stated in Article 1 of the contested decision that three of the five tax measures which in its view make up the STL system constituted State aid ‘to the EIGs and their investors’. The measures in question are early depreciation (measure 2) and the application of the tonnage tax scheme (measure 4), as clarified in Article 50(3) RIS (measure 5). Article 4(1) of the contested decision provides, however, that the Kingdom of Spain is to recover the incompatible aid granted under the scheme referred to in Article 1 ‘from the EIG investors that have benefited from it, without the possibility for such recipients to transfer the burden of recovery to other persons’.

116 In that regard, it must be stated that, while the EIGs benefited from the three tax measures referred to in Article 1 of the contested decision, it was the members of the EIGs that benefited from the economic advantages arising from those three measures. As is clear from recital 140 of the contested decision (see paragraph 41 above), the principle of tax transparency applicable to the EIGs is not called into question by the Commission in this instance. On the basis of that principle, the tax advantages conferred on the EIGs set up for the purposes of the STL system can benefit only their members, whom the Commission describes as mere ‘investors’ (see paragraph 12 above). The investors, moreover, are the only entities referred to in the recovery order imposed in Article 4(1) of the contested decision.

117 In the absence of an economic advantage in favour of the EIGs, the Commission was therefore wrong to conclude, in Article 1 of the contested decision, that they had benefited from State aid within the meaning of Article 107(1) TFEU.

118 Since it is the investors, and not the EIGs, that benefited from the tax and economic advantages resulting from the STL system, it is appropriate to examine, on the basis of the parties’ arguments, whether the advantages obtained by the investors are selective, are liable to distort competition and affect trade between Member States and whether the contested decision contains a sufficient statement of reasons concerning the analysis of those criteria.

b) The condition relating to selectivity

119 As stated in paragraph 97 above, the Commission concluded, in essence, in the contested decision that the STL system was a ‘system’ composed of five tax measures, three of which satisfied all the conditions laid down in Article 107(1) TFEU, including the criterion relating to selectivity.

120 As recalled in paragraphs 39 to 46 above, the Commission analysed the selective nature of each of the tax measures which in its view go to make up the STL system, examining them individually in recitals 128 to 154 of the contested decision and then analysing globally the selectivity of the STL system as a ‘system’, in recitals 155 to 157 of the contested decision. The Commission states, in recital 120 of the contested decision, that the individual analysis of the measures making up the STL system and their global examination as a ‘system’ are ‘complementary and lead to consistent conclusions’ (see paragraph 35 above).

121 As regards the individual analysis carried out by the Commission, measure 2 (early depreciation) was classified as ‘selective’ because the grant of that advantage depends on authorisation granted by the tax administration on the basis of a discretionary power. The exercise of that discretionary power led the tax administration to grant those authorisations only in the case of acquisitions of sea-going vessels in the context of the STL system and not in other circumstances (recitals 132 to 139 of the contested decision). Measure 4 (application of the tonnage tax system to EIGs set up for the purposes of the STL system) and measure 5 (Article 50(3) RIS) are selective, because they favoured certain activities, namely bareboat chartering (recitals 141 to 144 of the contested decision) and the acquisition of vessels through leasing contracts previously authorised by the tax administration and the resale of those vessels (recitals 145 to 154 of the contested decision).

122 As regards the global analysis carried out by the Commission, it is appropriate to refer to recital 156 of the contested decision, which is worded as follows: ‘Looking at the STL as a whole, the advantage is selective because it was subject to the discretionary powers conferred on the tax administration by the compulsory prior authorisation procedure and by the imprecise wording of the conditions applicable to early depreciation. Since other measures applicable only to maritime transport activities eligible under the Maritime Guidelines — in particular Article 50(3) RIS — are dependent on that prior authorisation, the whole STL system is selective. As a result, the tax administration would only authorise STL operations to finance sea-going vessels (sectoral selectivity). As confirmed by the statistics provided by Spain, all the 273 STL operations organised until June 2010 concern sea-going vessels’. The Commission therefore concluded that the advantage arising from the STL as a whole could be regarded as selective on the basis of the discretionary power identified in the context of the individual analysis of the selectivity of measure 2.

123 Furthermore, the Commission maintained, in recital 157 of the contested decision, that ‘the scheme favours certain activities, namely the acquisition of sea-going vessels through leasing contracts, in particular with a view to their bareboat chartering and subsequent resale’. Those activities correspond to the activities which, according to the contested decision, are carried out by the EIGs set up for the purposes of the STL and benefit from the application of measures 2, 4 and 5. According to the individual analysis referred to in paragraph 121 above, each of those measures confers, de jure and de facto, a selective advantage on the undertakings carrying out those activities (recitals 132 to 139 and 141 to 154 of the contested decision).

124 It thus follows from the contested decision that the measures going to make up the STL, taken individually and as a whole as a ‘system’, are selective for two reasons. First, the STL as a ‘system’ is selective on the ground that the tax administration, on the basis of a discretionary power, authorises the benefit of the advantages at issue only to ‘STL activities to finance sea-going vessels (sectoral selectivity)’, operations in which the investors participate. Second, the selectivity of the STL also arises from the selective nature of the three component tax measures, taken individually. Those measures favoured, de jure and de facto, only certain activities.

125 As already indicated in paragraph 118 above, it is appropriate to examine, in the light of the arguments of the Kingdom of Spain, Lico and PYMAR, whether those two reasons are capable of establishing that the tax and economic advantages from which the investors benefited were selective and whether the decision is sufficiently reasoned.

126 Before examining those questions, it is appropriate to clarify the scope of the arguments put forward by the Kingdom of Spain, Lico and PYMAR in answer to certain arguments raised by the Commission. In Case T‑515/13, the Commission claimed that the Kingdom of Spain had not disputed in its application the global analysis of selectivity carried out in recitals 155 to 163 of the contested decision. In the Commission’s submission, the action could not succeed unless the Kingdom of Spain succeeded in showing that those measures, considered individually and as a whole, do not constitute State aid; and as the Commission’s global analysis was not called into question by the Kingdom of Spain, the latter’s arguments relating to the individual analysis of the measures, are ineffective. At the hearing in Case T‑719/13, the Commission claimed that Lico and PYMAR had not disputed the individual analysis of measures 2, 4 and 5 in the context of their first plea.

127 In that regard, it must be stated that, at the beginning of its application, the Kingdom of Spain puts forward certain general arguments disputing the Commission’s analysis in relation to selectivity as a whole. Those arguments were further developed by the Kingdom of Spain in answer to a written question from the Court (see paragraph 71 above) and at the hearing in Case T‑515/13. Furthermore, the Kingdom of Spain disputes in its application the discretionary power identified by the Commission in the context of the individual analysis of selectivity of measure 2. Since the Commission relies on that discretionary power in order to establish, in recital 156 of the contested decision, the selectivity of the STL as a whole, the arguments formulated by the Kingdom of Spain are also capable of calling that analysis into question.

128 As regards Lico and PYMAR, the Commission was wrong to claim at the hearing that they had not disputed the individual analysis of measures 2, 4 and 5. In fact, as already indicated (see paragraph 98 above), when Lico and PYMAR deny that the STL constitutes a ‘State aid scheme’, they are also referring to the components of the STL, referred to in Article 1 of the contested decision. It should also be observed that the arguments put forward by Lico and PYMAR in connection with selectivity challenge the Commission’s findings in recitals 156 and 157 of the contested decision. As indicated in paragraphs 122 and 123 above, the findings made by the Commission in those recitals are based on the individual analysis of measures 2, 4 and 5.

129 It follows that the Commission’s arguments concerning the limited scope of the arguments put forward by the Kingdom of Spain, Lico and PYMAR are unfounded.

Authorisations granted by the tax administration, on the basis of a discretionary power, solely to STL transactions for the financing of sea-going vessels

130 The Kingdom of Spain, Lico and PYMAR observe that the possibility of participating in the STL structures and, accordingly, of obtaining the advantages at issue were open to any investor in all sectors of the economy, without any precondition or restriction. The advantages obtained by the investors cannot therefore be considered to be selective, in particular in the light of the judgments in Autogrill España v Commission, cited in paragraph 71 above (EU:T:2014:939), and Banco Santander and Santusa v Commission, cited in paragraph 71 above (EU:T:2014:938).

131 Furthermore, the Kingdom of Spain, Lico and PYMAR deny that the tax administration had any discretionary power in the context of the authorisation procedure laid down for early depreciation (measure 2). Lico and PYMAR further maintain that, in the context of that authorisation procedure, the control exercised by the administration never related to the investors. At the hearing, the Kingdom of Spain also claimed that the sole purpose of the administrative authorisation was to ascertain that the asset to which early depreciation could apply satisfied the criteria of the applicable legislation, which has no connection with the desire to select, de facto or de jure, certain undertakings.

132 In its defence in Case T‑719/13, the Commission contends that the measure at issue is selective vis-à-vis investors, because only undertakings which make a certain type of investment through an EIG benefit from it, while undertakings which make similar investments in the context of other operations cannot benefit from it. It submits that such an analysis is consistent with the case-law (judgments of 15 July 2004 in Spain v Commission, C‑501/00, ECR, EU:C:2004:438, paragraph 120; 15 December 2005 in Italy v Commission, C‑66/02, ECR, EU:C:2005:768, paragraphs 97 and 98; and in Associazione italiana del risparmio gestito and Fineco Asset Management v Commission, cited in paragraph 89 above, EU:T:2009:50, paragraph 156).

133 In answer to a written question from the Court in Cases T‑515/13 and T‑719/13 (see paragraph 71 above), the Commission claimed that the approach taken in the contested decision was not a new approach. The case-law has taken the same approach in various cases relating to tax advantages reserved for undertakings making a certain type of investment. In that regard, the Commission refers to the judgment in Spain v Commission, cited in paragraph 133 above (EU:C:2004:438), and to the judgment of 6 March 2002 in Diputación Foral de Álava and Others v Commission (T‑92/00 and T‑103/00, ECR, EU:T:2002:61).