JUDGMENT OF THE GENERAL COURT (Sixth Chamber)

21 November 2013 (*)

(Community design – Invalidity proceedings – Registered Community design representing a corkscrew – Earlier national design – Ground for invalidity – Lack of individual character – Overall impression not different – Informed user – Degree of freedom of the designer – Articles 4, 6 and 25(1)(b) of Regulation (EC) No 6/2002)

In Case T‑337/12,

El Hogar Perfecto del Siglo XXI, SL, established in Madrid (Spain), represented by C. Ruiz Gallegos and E. Veiga Conde, lawyers,

applicant,

v

Office for Harmonisation in the Internal Market (Trade Marks and Designs) (OHIM), represented by Ó. Mondéjar Ortuño, acting as Agent,

defendant,

the other party to the proceedings before the Board of Appeal of OHIM, intervener before the General Court, being

Wenf International Advisers Ltd, established in Tortola, British Virgin Islands (United Kingdom), represented by J.L. Rivas Zurdo, E. Seijo Veiguela and I. Munilla Muñoz, lawyers,

ACTION brought against the decision of the Third Board of Appeal of OHIM of 1 June 2012 (Case R 89/2011‑3) in relation to invalidity proceedings between Wenf International Advisers Ltd and El Hogar Perfecto del Siglo XXI, SL,

THE GENERAL COURT (Sixth Chamber),

composed of H. Kanninen, President, G. Berardis (Rapporteur) and C. Wetter, Judges,

Registrar: E. Coulon,

having regard to the application lodged at the Court Registry on 30 July 2012,

having regard to the response of OHIM lodged at the Court Registry on 30 October 2012,

having regard to the response of the intervener lodged at the Court Registry on 26 October 2012,

having regard to the fact that no application for a hearing was submitted by the parties within the period of one month from notification of closure of the written procedure, and having therefore decided, acting upon a report of the Judge-Rapporteur and pursuant to Article 135a of the Rules of Procedure of the General Court, to give a ruling without an oral procedure,

gives the following

Judgment

Background to the dispute

1 On 22 November 2007, the applicant – El Hogar Perfecto del Siglo XXI, SL – filed an application for registration of a Community design with the Office for Harmonisation in the Internal Market (Trade Marks and Designs) (OHIM) pursuant to Council Regulation (EC) No 6/2002 of 12 December 2001 on Community designs (OJ 2002 L 3, p. 1).

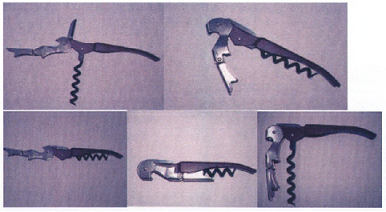

2 The design in respect of which registration was sought is represented as follows:

3 The contested design is intended to be applied to ‘corkscrews’ in Class 07-06 of the Locarno Agreement of 8 October 1968 Establishing an International Classification for Industrial Designs, as amended.

4 On the same day as that application was filed, the contested design was registered under No 000830831-0001 and published in Community Designs Bulletin No 2007/191 of 14 December 2007.

5 On 16 April 2009, the intervener – Wenf International Advisers Ltd – applied to OHIM for a declaration that the contested design was invalid. The ground relied on in support of the application was that referred to in Article 25(1)(b) of Regulation No 6/2002 which provides that a Community design must be declared invalid if it does not meet the requirements under Articles 4 to 9 of that regulation. In the application for a declaration of invalidity, the intervener submitted that the contested design was not new and that it lacked individual character for the purposes of Article 4 of Regulation No 6/2002, read in conjunction with Articles 5 and 6 of that regulation.

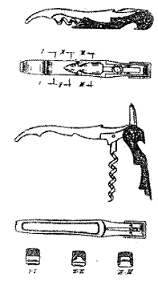

6 In support of its application for a declaration of invalidity, the intervener relied on the design registered in Spain on 7 September 1994, under No 131750, which was made available to the public through its publication in the Boletín Oficial de la Propiedad Industrial (Spanish Intellectual Property Bulletin) on 16 October 1994 and was to be applied to ‘bottle openers’. The earlier design is represented as follows:

7 On 12 November 2010, the Cancellation Division of OHIM upheld the application for a declaration of invalidity on the ground that the contested design lacked individual character. The Cancellation Division stated that the overall impression produced by the contested design was no different to that produced by the earlier design, in the light of the many similarities between them, such as the appearance of the curved handle, the element made up of two plates fixed together with a pin in an identical position, and the small blade located in an identical position. The Cancellation Division also stated that those similarities fell to be assessed in the same way, whether the devices were open or closed. Lastly, the Cancellation Division found that the designer had enjoyed a high degree of freedom, since – as emerged from the documents before OHIM – the device could have been designed on the basis of many different approaches.

8 On 11 January 2011, the applicant filed a notice of appeal with OHIM, under Articles 55 to 60 of Regulation No 6/2002, against the decision of the Cancellation Division.

9 By decision of 1 June 2012 (‘the contested decision’), the Third Board of Appeal of OHIM dismissed the appeal. After rejecting the applicant’s argument that the intervener had acted in bad faith, the Board of Appeal examined the individual character of the contested design. This led the Board of Appeal to identify the informed user of the design as being both a private individual and a professional who uses the products covered by that design – ‘corkscrews’ – and to find that the designer had enjoyed a high degree of freedom. Although such devices must, as a matter of necessity, have certain functional parts, they may, according to the Board of Appeal, be designed and put together in a number of ways. The Board of Appeal found that the two designs at issue have non-functional elements in common – that is to say, the design of the handle and the positioning of the small blade – and, as a result, they do not produce a different overall impression on the informed user. As regards, more specifically, the similarity of the handles, the Board of Appeal stated that, on the one hand, the shape of the handle had a significant impact on the overall appearance of a corkscrew, since it was the largest element enclosing, in whole or in part, the other elements, and, on the other hand, it played a decisive role in the overall impression produced by such goods when the device was closed. In that connection, the Board of Appeal stated that, in the two designs at issue, the handle had been designed in such a way as to leave visible the same parts of the spiral screw and lever when the corkscrew was closed. The difference between the handles of the designs at issue – that is to say, the design of the inner surface – is not sufficient, therefore, to alter the overall impression produced by those designs on the informed user.

Forms of order sought

10 The applicant claims that the Court should:

– annul the contested decision;

– order OHIM and the intervener to pay the costs.

11 OHIM and the intervener contend that the Court should:

– dismiss the action;

– order the applicant to pay the costs.

Law

12 The applicant puts forward two pleas in law in support of its action, alleging: (i) infringement of Articles 4 and 6(1) of Regulation No 6/2002, read in conjunction with Article 25(1)(b) of that regulation, so far as concerns the concept of ‘informed user’, for the purposes of assessing the individual character of the contested design; and (ii) infringement of Articles 4 and 6(2) of Regulation No 6/2002, read in conjunction with Article 25(1)(b) of that regulation, so far as concerns the degree of freedom enjoyed by the designer in developing the contested design, for the purposes of assessing its individual character.

13 As both those pleas in law imply that the Board of Appeal made errors when assessing the individual character of the contested design, the Court considers it appropriate to examine them together.

14 The applicant claims, in essence, that the Board of Appeal erred in its assessment of the individual character of the contested design. More specifically, it submits that the Board of Appeal erred in its assessment of the concept of ‘informed user’ – which influenced its assessment of the overall impression produced by the contested design on the informed user – and the degree of freedom enjoyed by the designer. According to the applicant, the differences between the contested design and the earlier design are of such a kind that the overall impression produced on the informed user is different and the contested design is not therefore devoid of individual character.

15 OHIM and the intervener dispute the applicant’s arguments.

16 Article 25(1)(b) of Regulation No 6/2002 provides that a Community design may be declared invalid if it does not meet the requirements under Articles 4 to 9 of that regulation.

17 Under Article 4 of Regulation No 6/2002, a design is to be protected by a Community design to the extent that it is new and has individual character.

18 Under Article 6(1)(b) of Regulation No 6/2002, a registered Community design is to be considered to have individual character if the overall impression it produces on the informed user differs from the overall impression produced on such a user by any design which has been made available to the public before the date of filing the application for registration or, if a priority is claimed, the date of priority.

19 Article 6(2) of Regulation No 6/2002 states that, in assessing individual character, the degree of freedom of the designer in developing the design is to be taken into consideration.

20 For the purposes of examining the individual character of the contested design, it is therefore necessary to establish whether the Board of Appeal erred in its successive findings regarding the informed user of that design and the freedom enjoyed by the designer in developing the design, and then in its comparison of the overall impressions produced on the informed user by the designs at issue.

The informed user

21 It follows from the case‑law that the concept of ‘informed user’ must be understood as lying somewhere between that of the average consumer, applicable in trade mark matters, who need not have any specific knowledge and who, as a rule, makes no direct comparison between the trade marks at issue, and the sectoral expert, who is an expert with detailed technical expertise (Case C‑281/10 P PepsiCo v Grupo Promer Mon Graphic [2011] ECR I‑10153, paragraph 53).

22 Thus, although the informed user is not the reasonably well-informed and reasonably observant and circumspect average consumer who normally perceives a design as a whole and does not proceed to analyse its various details, nor is he an expert or specialist capable of observing in detail the minimal differences that may exist between the designs at issue (PepsiCo v Grupo Promer Mon Graphic, paragraph 21 above, paragraph 59).

23 The status of ‘user’ implies that the person concerned uses the product covered by the design in accordance with the purpose for which that product is intended (Case T‑153/08 Shenzhen Taiden v OHIM – Bosch Security Systems (Communications equipment) [2010] ECR II‑2517, paragraph 46). The qualifier ‘informed’ suggests, in addition, that, without being a designer or a technical expert, the user knows the various designs which exist in the sector concerned, possesses a certain degree of knowledge with regard to the features which those designs normally include, and, as a result of his interest in the products concerned, shows a relatively high degree of attention when he uses them (PepsiCo v Grupo Promer Mon Graphic, paragraph 21 above, paragraph 59, and Communications equipment, paragraph 47).

24 Accordingly, the concept of the informed user may be understood as referring, not to a user of average attention, but to a user who is particularly observant, either because of his personal experience or because of his extensive knowledge of the sector in question (PepsiCo v Grupo Promer Mon Graphic, paragraph 21 above, paragraph 53; the judgment of 25 April 2013 in Case T‑80/10 Bell & Ross v OHIM – KIN (Wristwatch case), not published in the ECR, paragraph 103).

25 However, that factor does not imply that the informed user is able to distinguish, beyond the experience gained by using the product concerned, the aspects of the appearance of the product which are dictated by the product’s technical function from those which are arbitrary. In consequence, an informed user is a person who has some awareness of the existing designs in the sector concerned, but without knowing which aspects of the product in question are dictated by technical function (Wristwatch case, paragraph 24 above, paragraph 104, and the judgment of 9 September 2011 in Case T‑11/08 Kwang Yang Motor v OHIM – Honda Giken Kogyo (Internal combustion engine), not published in the ECR, paragraph 26).

26 In the present case, the Board of Appeal first of all pointed out, in paragraph 16 of the contested decision, that the ‘sector in question relates to corkscrews, that is to say, devices which remove the cork from a bottle of wine’. It is clear from paragraph 19 of the contested decision, describing the functional elements of those devices, that – contrary to the assertions made by the applicant – the Board of Appeal delimited the sector in question as relating only to lever-action corkscrews. The Board of Appeal went on to state, in paragraph 17 of the contested decision, that the informed user could be ‘both a private individual who uses those devices at home and a professional (waiter, sommelier) who uses them in a restaurant’. According to the Board of Appeal, such a user is informed, in the sense that ‘he is knowledgeable about wine and related accessories to make the most of that knowledge and, without being a designer, possesses a certain degree of knowledge, as a result of his interest and partiality [to wine], on what the market offers in terms of wine-bottle openers’. In other words, according to the Board of Appeal, that person, without being an expert in industrial design, is aware of what the market offers and the basic features of the product.

27 Contrary to the assertions made by the applicant, that definition of ‘informed user’ is correct and consistent with the principles of case‑law set out in paragraphs 21 to 25 above. According to that case‑law, the informed user knows the various designs which exist in the sector concerned, possesses a certain degree of knowledge with regard to the features which those designs normally include, and, as a result of his interest in the products concerned, shows a relatively high degree of attention when he uses them, with the result that the concept of the informed user can be understood as referring to a user who is particularly observant, either because of his personal experience or because of his extensive knowledge of the sector in question.

28 In that regard, it must also be pointed out that, not only has the applicant failed to substantiate its claims that the informed user is exclusively a ‘person who works with wine and/or in the supply thereof’ and that a private individual would rarely use a lever-action corkscrew of the kind at issue, since such lever-action corkscrews are not sold in retail shops, but it has even failed to establish that limiting the concept of ‘informed user’ to cover only professionals would put in question the definition of ‘informed user’ decided upon by the Board of Appeal in the second sentence of paragraph 17 of the contested decision.

29 Moreover, even if – as the applicant claims – the contested design could be regarded as a promotional item that wine producers, after personalising the visible surface of the handle, offer as a gift, the definition of ‘informed user’ does not change, since it covers – as the Board of Appeal found – both the professional who acquires such items in order to distribute them to the final users and those final users themselves (see, to that effect, Case T‑68/10 Sphere Time v OHIM – Punch (Watch attached to a lanyard) [2011] ECR II‑2275, paragraph 53).

30 The Board of Appeal did not therefore err in finding that the informed user of the design in question is both the private individual and the professional who uses the products covered by that design.

The degree of freedom of the designer

31 It should be borne in mind that, in the assessment of the individual character of the design, its visible features and accordingly the overall impression on the informed user of that design, the designer’s degree of freedom in developing the design at issue must be taken into account (see Internal combustion engine, paragraph 25 above, paragraph 31 and the case‑law cited).

32 According to the case‑law, the designer’s degree of freedom in developing his design is established, inter alia, by the constraints of the features imposed by the technical function of the product or an element thereof, or by statutory requirements applicable to the product. Those constraints result in a standardisation of certain features, which will thus be common to the designs applied to the product concerned (see Internal combustion engine, paragraph 25 above, paragraph 32 and the case‑law cited).

33 As a consequence, the greater the designer’s freedom in developing a design, the less likely it is that minor differences between the designs at issue will be sufficient to produce a different overall impression on the informed user. Conversely, the more restricted the designer’s freedom in developing a design, the more likely minor differences between the designs at issue will be sufficient to produce a different overall impression on the informed user. Accordingly, if the designer enjoys a high degree of freedom in developing a design, this reinforces the conclusion that the designs which do not have significant differences produce the same overall impression on the informed user (see Internal combustion engine, paragraph 25 above, paragraph 33 and the case‑law cited).

34 In the present case, the Board of Appeal found in paragraph 19 of the contested decision that, although there are some elements essential to a corkscrew if it is to fulfil its purpose, the designer’s degree of freedom in relation to such a product is high. The fact that it is necessary for a corkscrew to have parts such as a helical screw intended to enter and embed itself in the cork, a handle to control the device, one or two levers to push against the neck of the bottle, and a small blade to cut the foil covering the cork, does not preclude those parts from being designed and incorporated in different ways, but with no loss of functionality. By way of example, the Board of Appeal added that the small blade could be positioned at either end of the device and that the handle could take a variety of different forms and vary in length and thickness, without the corkscrew’s functionality or ease of use being affected.

35 The applicant disputes that finding. It maintains that the structural characteristics of corkscrews of that type have already been defined and imposed by their purpose and by the needs of those for whom they are intended, that is to say, according to the applicant, professionals in the hotel and catering business and wine producers. More specifically, of the four features required because of a corkscrew’s technical function – the helical screw, the two levers, the handle and the small blade – only the handle and the small blade can be designed differently. Moreover, so far as the blade is concerned, the applicant argues that to position it anywhere else on the handle of the type of corkscrew in question would ultimately make it ineffective, unsuitable for its purpose and dangerous. The designer’s degree of freedom in relation to a double lever corkscrew is thus limited.

36 In that regard, it must be noted that it is true that some features of a lever-action corkscrew are essential and necessary for all corkscrews of that type in order to fulfil their purpose. However, as OHIM and the intervener have correctly observed, the constraints of functionality relating to the presence of certain features on a lever-action corkscrew are not liable to affect its form or overall appearance significantly (see, to that effect, Wristwatch case, paragraph 24 above, paragraph 118), since the only technical constraints that must be adhered to are the dimensions of the lever – whether a single or double lever – the existence of notches at one end of it, and the position of the screw and its distance from the lever. In particular, the handle, which, as the Board of Appeal correctly observed, is the central and biggest element of the corkscrew, may take various forms and vary in size, and the position of the small blade may differ.

37 It is apparent from the documents before OHIM forwarded to the Court that there are designs for lever-action corkscrews with varying shapes and configurations that differ from those used in the contested design. By way of example, the Court observes, first of all, that differences may be noted with regard to the dimensions and shape of the handle, which may be straight or curved, rounded or oblong, and with regard to the visible part of the other features of a corkscrew which may be included in the handle. There are also differences with regard to the presence and position of a bottle-opener or a small blade. In that regard, the applicant has not adduced any evidence substantiating its assertion that altering the position of the small blade on the handle would make it unsuitable for its purpose and even dangerous.

38 It follows that the design and shape of the handle and the position of the abovementioned features are not dictated by requirements of functionality. The general appearance of the corkscrew is not therefore determined by the existence of technical constraints and may vary considerably.

39 The Board of Appeal was therefore correct to find, in essence, in paragraph 19 of the contested decision, that the designer’s degree of freedom with regard to a corkscrew is high.

Comparison of the overall impressions produced by the designs at issue on the informed user

40 According to the Board of Appeal, the overall impression produced by the contested design on the informed user is no different from that produced by the earlier design on account, in essence, of similarities of shape, position and relative size of the various features of the corkscrew.

41 The Board of Appeal found, in essence, that the overall impression produced on the informed user was principally determined by the appearance of the handle, and by the position of certain features of the corkscrew. The Board of Appeal added that, in the light of the characteristics of that type of corkscrew – the essential characteristic being that it can be folded away and put in a pocket – the design and shape of the handle plays a decisive role in the overall impression produced.

42 The applicant challenges the Board of Appeal’s assessment. First of all, the applicant alleges that the Board of Appeal made an error of assessment in examining the designs at issue only when closed and not in an open or ready-to-use position. Next, the applicant claims that, when using the device, differences between the handle, blade, helical screw and the two levers can be identified. The applicant thus submits a detailed analysis of the designs at issue, maintaining that the characteristics of those designs are not identical and that, therefore, the overall impressions that they produce – if examined open – are different.

43 In the first place, it must be noted that the complaint that the Board of Appeal was wrong to examine the general external appearance of the designs at issue only when closed is based on a misreading of the contested decision. It is apparent from the contested decision that it was only in order to support the view that there are no significant differences in the designs of the handles of the designs at issue, which leave the same parts of the screw and lever visible when they are folded, that the Board of Appeal referred, in passing, in paragraphs 21(a) to 24 of the contested decision, to the product in question when closed. Moreover, it is clear from paragraph 5 of the contested decision that the Cancellation Division found that the many similarities between the two designs at issue may be assessed in the same way irrespective of whether the devices are open or closed. That conclusion was not disputed by the applicant before the Board of Appeal. In accordance with the case‑law, when the Board of Appeal confirms a lower-level decision of OHIM in its entirety, the decision of the Cancellation Division, together with its statement of reasons, forms part of the context in which the contested decision was adopted, a context which is known to the applicant and which enables the Court to exercise in full its jurisdiction to review legality as regards the question whether the assessment of individual character of the design at issue was well founded (see, to that effect, the judgment of 6 October 2011 in Case T‑246/10 Industrias Francisco Ivars v OHIM – Motive (Mechanical speed reducer), not published in the ECR, paragraph 20, and the judgment of 22 May 2012 in Case T‑179/11 Sports Eybl & Sports Experts v OHIM – Seven (SEVEN SUMMITS), not published in the ECR, paragraph 50). Therefore, contrary to what the applicant maintains, in its assessment of the similarities between the designs at issue, the Board of Appeal, like the Cancellation Division, took account of the device in both the open and closed positions.

44 In that regard, it is to be noted, first of all, that the length of the handle of the contested design is only slightly shorter than that of the handle of the earlier design, and that no significant difference can be found to exist in relation to the overall dimensions, or the proportions and arrangement of the various features on the handles, of the designs at issue, irrespective of whether they are open or closed. Moreover, a direct comparison, as suggested by the applicant, of samples of actual products included in the documents before OHIM forwarded to the Court does not call that finding into question.

45 In addition, if, as the applicant claims, account should be taken solely of the overall impressions produced by the two designs on the informed user when he is using the product at issue, that is to say, when the product is open, it should be observed that, during its use, which begins when the corkscrew is opened up, it remains in the user’s grasp. For the purposes of the assessment of the overall impression produced by the designs at issue, it is therefore appropriate to consider that the informed user will, when using the corkscrews corresponding to the designs at issue for their intended purpose, see a small part of the corkscrew – in essence, the double lever and integrated bottle-opener, the small blade and the helical screw. However, in such a situation, the details of the products represented by the designs at issue, to which the applicant refers, will be hidden from the user’s view because of the way corkscrews must be used in practice and, for that reason, will not have any great impact on how those designs are perceived by the informed user (see, to that effect, Wristwatch case, paragraph 24 above, paragraphs 133 and 134).

46 Accordingly, having regard to the fact that, as the case‑law has made clear, the assessment must concern the overall impression produced by a design on the informed user, thus including the manner in which the product represented by that design is used (see, to that effect, Communications Equipment, paragraph 23 above, paragraph 66, and Watch attached to a lanyard, paragraph 29 above, paragraph 78), the Board of Appeal cannot be criticised, in view of the characteristics of lever-action corkscrews which are designed specifically to fold up, for having also taken account of the impression produced by the designs at issue on the informed user when the corkscrews in question are closed. In addition, it is apparent from the documents before OHIM forwarded to the Court that, within the industrial sector concerned, the products at issue are mainly, and sometimes exclusively, represented in the closed position which is, as a general rule, the basic position of lever-action corkscrews. Moreover, it is when a corkscrew is in that position that it is possible to discern the overall shape of the design representing it.

47 In the second place, it should be noted that the differences between the designs at issue, to which the applicant draws attention and which entail an examination of the products represented by them in the opened-up position, are either irrelevant or insignificant. The same is true as regards the functional elements mentioned by the applicant, which are not sufficiently striking to have any influence on the overall impression produced by those designs.

48 First, as regards the handle, it is true, as the Board of Appeal also observed in paragraph 24 of the contested decision, that there is a difference between the designs at issue with regard inter alia to the design of the inner surface which, in the earlier design, has small dents whereas, in the contested design, it is smooth. However, that difference is not particularly pronounced since (i) the curve of the handle of the product represented by the contested design and that of the device represented by the earlier design are very similar, even if the first is less marked, and (ii) the arrangement of the different features around the handle is the same in both of the designs at issue, as is the part that remains visible when the handle is closed. The Court therefore finds that the slightly different design of the handle of the contested design cannot, as the Board of Appeal correctly stated, offset the similarities found and is thus not sufficient to confer individual character on the design.

49 Second, so far as concerns the small blade, contrary to what the applicant claims, the Court finds, first of all, that a comparison of the designs at issue does not show that the small blade of the earlier mark is, in essence, smaller or less visible than the blade of the contested design or that it has a different shape from that of the contested design. Next, with regard to the cutting edge of the blade, it suffices to note that it is not clear from the images of the earlier design whether the blade is smooth or, in any event, not serrated. However, if, as the applicant suggests, samples of actual products included in the documents before OHIM forwarded to the Court are examined, it is apparent that the small blade on the earlier design is not at all smooth but, like the blade on the contested design, has a serrated cutting edge. In any event, no significant difference between the blades of the products represented by the designs at issue can be observed.

50 Third, as regards the helical screws of the products represented by the designs at issue, the applicant claims that there is, on the one hand, a difference in colour between them and, on the other, that they are made of or coated with different materials. According to the applicant, those differences are also apparent from a comparison of samples of actual products included in the documents before OHIM forwarded to the Court. In that regard, the fact that the screw of the contested design is represented in black, whereas the screw of the earlier design is represented in white, is not significant, given that no colour has been claimed for the contested design (see, to that effect, Watch attached to a lanyard, paragraph 29 above, paragraph 82). In any event, it must be observed that, contrary to what the applicant claims, it is apparent from a comparison of samples of actual products that the colour of the screw is black in both the product corresponding to the contested design and the product corresponding to the earlier design. The same is true of the materials which the two screws are alleged to be made of or coated in.

51 Fourth, so far as the double lever is concerned, the Court finds that the differences invoked by the applicant with regard to the finish of the two support notches are not apparent from a comparison of the pictures of the designs at issue. In any event, they are so imperceptible that only a very detailed and thorough technical examination of the two actual products – which would not correspond, as stated in paragraph 22 above, to the examination undertaken by the informed user – would detect them, if indeed there are any. With regard to the difference between the surface of the two levers, which is smooth in the contested design and grooved in the earlier design, it must be noted that the absence of grooves in the contested design is not likely to have a significant effect on the overall impression produced on the informed user and is not sufficient, in itself, to confer individual character on that design.

52 Fifth, as regards the disadvantages or operational difficulties associated with the handle, small blade, screw and double lever of the earlier design which are allegedly resolved by the contested design, it must be stated that, even if they were established, such disadvantages or operational difficulties are not relevant for the purpose of proving the individual character of the contested design. The individual character of a design is to be assessed, in accordance with Article 6 of Regulation No 6/2002, by comparing the overall impressions produced by the designs at issue on the informed user and by taking into consideration the degree of freedom of the designer. The criterion relied on by the applicant, relating to the disadvantages and various operational difficulties of the earlier design which have allegedly been resolved in the contested design, is therefore not among those which may be taken into account for the purposes of assessing the individual character of a design. Moreover, as is apparent from Articles 1 and 3 of Regulation No 6/2002, the law on designs seeks to protect the appearance of a product and not its methods of use or operation. Lastly, and in any event, it must be observed that the applicant has, on the one hand, not substantiated its arguments and, on the other, that conclusions relating to the use or operation of the products represented by the designs at issue cannot in the present case be drawn from a straightforward comparison of those designs.

53 The other differences relied on by the applicant so far as concerns certain characteristics of the operative part of the handle, the small blade, the bottle-opener, the area where the spiral is fixed, and the ‘opening’ area are insignificant in the overall impression produced by the designs at issue. Those differences are not sufficiently pronounced to distinguish the two devices in the perception of the informed user, who, as was stated in paragraph 22 above, will not go beyond a certain level of examination and detail.

54 The Board of Appeal did not therefore err in finding, in paragraph 26 of the contested decision, that the contested design and the earlier design do not produce different overall impressions on the informed user and that the contested design lacked individual character within the meaning of Article 6 of Regulation No 6/2002.

55 In the light of all the above considerations, the action must be dismissed in its entirety.

Costs

56 Under Article 87(2) of the Rules of Procedure of the General Court, the unsuccessful party is to be ordered to pay the costs if they have been applied for in the successful party’s pleadings.

57 Since the applicant has been unsuccessful, it must be ordered to pay the costs, in accordance with the forms of order sought by OHIM and the intervener.

On those grounds,

THE GENERAL COURT (Sixth Chamber)

hereby:

1. Dismisses the action;

2. Orders El Hogar Perfecto del Siglo XXI, SL to pay the costs.

Delivered in open court in Luxembourg on 21 November 2013.

[Signatures]