JUDGMENT OF THE GENERAL COURT (Seventh Chamber)

4 February 2014 (*)

(Community design – Invalidity proceedings – Registered Community design representing a cuboid armchair – Earlier design – Ground for invalidity – Individual character – Different overall impression – Article 6 and Article 25(1)(b) of Regulation (EC) No 6/2002)

In Case T‑339/12,

Gandia Blasco, SA, established in Valencia (Spain), represented by I. Sempere Massa, lawyer,

applicant,

v

Office for Harmonisation in the Internal Market (Trade Marks and Designs) (OHIM), represented by A. Folliard-Monguiral, acting as Agent,

defendant,

the other party to the proceedings before the Board of Appeal of OHIM, intervener before the General Court, being

Sachi Premium-Outdoor Furniture, Lda, established in Estarreja (Portugal), represented by M. Oehen Mendes and M. Paes, lawyers,

ACTION brought against the decision of the Third Board of Appeal of OHIM of 25 May 2012 (Case R 970/2011‑3) in relation to invalidity proceedings between Gianda Blasco, SA and Sachi Premium-Outdoor Furniture, Lda,

THE GENERAL COURT (Seventh Chamber),

composed of M. Van der Woude, President, I. Wiszniewska-Białecka (Rapporteur) and I. Ulloa Rubio, Judges,

Registrar: E. Coulon,

having regard to the application lodged at the Court Registry on 30 July 2012,

having regard to OHIM’s response lodged at the Court Registry on 21 November 2012,

having regard to the intervener’s response lodged at the Court Registry on 16 November 2012,

having regard to the fact that no application for a hearing was submitted by the parties within the period of one month of notification of closure of the written procedure, and having therefore decided, acting upon a report of the Judge‑Rapporteur and pursuant to Article 135a of the Rules of Procedure of the General Court, to give a ruling without an oral procedure,

gives the following

Judgment

Background to the dispute

1 The intervener, Sachi Premium-Outdoor Furniture, Lda, is the holder of the Community design filed with the Office for Harmonisation in the Internal Market (Trade Marks and Designs) (OHIM) on 14 May 2009, registered on that same day under No 1512633‑0001 (‘the contested design’) and published in the Community Designs Bulletin No 116/2009 of 18 June 2009.

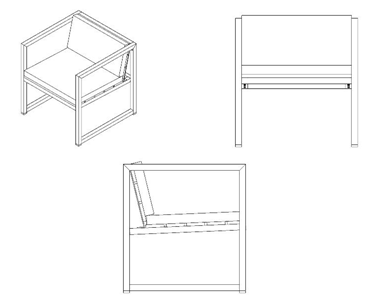

2 The contested design, intended to be applied to ‘armchairs, loungers’, is represented as follows:

3 On 1 April 2010, the applicant, Gandia Blasco, SA, applied to OHIM for a declaration that the contested design was invalid, based on Articles 4 to 9 of Council Regulation (EC) No 6/2002 of 12 December 2001 on Community designs (OJ 2002 L 3, p. 1).

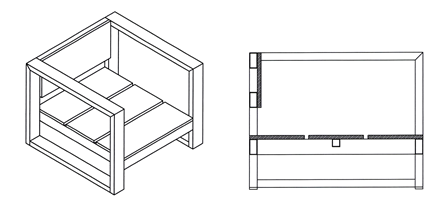

4 In support of its application for a declaration of invalidity, the applicant relied on the Community design registered on 9 December 2003 under No 52113‑0001 (‘the earlier design’) for ‘armchairs’, represented as follows:

5 By decision of 28 February 2011, the Invalidity Division rejected the application for a declaration of invalidity on the ground that the contested design was new and had individual character within the meaning of Article 25(1)(b) of Regulation No 6/2002, read in conjunction with Articles 5 and 6 of that regulation.

6 On 6 May 2011, the applicant filed a notice of appeal pursuant to Articles 55 to 60 of Regulation No 6/2002 against the decision of the Invalidity Division.

7 By decision of 25 May 2012, the Third Board of Appeal of OHIM dismissed the appeal. The Board of Appeal took the view that the differences between the designs at issue were sufficient to infer that they produced different overall impressions on the informed user. It concluded therefrom that the overall impression [produced by] the earlier design was not such as to deprive the contested design of its individual character under Article 6 of Regulation No 6/2002.

Forms of order sought

8 The applicant claims that the Court should:

– annul the decision of the Third Board of Appeal of OHIM of 25 May 2012 and declare the contested design invalid;

– make an order as to costs.

9 OHIM and the intervener contend that the Court should:

– dismiss the action;

– order the applicant to pay the costs.

Law

10 The applicant puts forward, in essence, a single plea in law based on infringement of Article 6 of Regulation No 6/2002.

11 The applicant claims that the contested design is devoid of individual character. The overall impression produced on the informed user by the contested design does not differ from the overall impression produced by the earlier design, since their main features are similar to a very high degree.

12 Under Article 6(1)(b) of Regulation No 6/2002, individual character falls to be assessed, in the case of a registered Community design, in the light of the overall impression produced on the informed user, which must be different from that produced by any design made available to the public before the date of filing of the application for registration or, if a priority is claimed, before the date of priority. Article 6(2) of Regulation No 6/2002 states that, for the purposes of that assessment, the designer’s degree of freedom in developing the design is to be taken into consideration.

13 As regards the concept of the ‘informed user’, by reference to which the individual character of the contested Community design falls to be assessed, the Board of Appeal identified that user, in the present case, as any person who ‘habitually purchases’ armchairs and puts them to their intended use and who has acquired information on the subject, inter alia, by browsing through catalogues of armchairs, going to relevant shops, downloading information from the internet, or who is a reseller of those products.

14 As regards the informed user’s level of attention, as the Board of Appeal has stated, according to the case-law, the concept of the informed user may be understood as referring, not to a user of average attention, but to a particularly observant one, either because of his personal experience or his extensive knowledge of the sector in question (Case C‑281/10 P PepsiCo v Grupo Promer Mon Graphic [2011] ECR I‑10153, paragraph 53).

15 It is also apparent from the case-law that, although the informed user is not the well-informed and reasonably observant and circumspect average consumer who normally perceives a design as a whole and does not proceed to analyse its various details, he is also not an expert or specialist capable of observing in detail the minimal differences that may exist between the designs at issue. Thus, the qualifier ‘informed’ suggests that, without being a designer or a technical expert, the user knows the various designs which exist in the sector concerned, possesses a certain degree of knowledge with regard to the features which those designs normally include, and, as a result of his interest in the products concerned, shows a relatively high degree of attention when he uses them (PepsiCo v Grupo Promer Mon Graphic, paragraph 14 above, paragraph 59).

16 The Board of Appeal took the view that the informed user in the present case was familiar with the product in accordance with the level of attention required in the case-law cited in paragraphs 14 and 15 above.

17 As regards the designer’s degree of freedom, according to the case-law, that freedom is established by, inter alia, the constraints of the features imposed by the technical function of the product or an element thereof, or by statutory requirements applicable to the product. Those constraints result in a standardisation of certain features, which will thus be common to the designs applied to the product concerned (judgments of 9 September 2011 in Case T‑11/08 Kwang Yang Motor v OHIM – Honda Giken Kogyo (Internal combustion engine), not published in the ECR, paragraph 32, and of 25 April 2013 in Case T‑80/10 Bell & Ross v OHIM – KIN (Wristwatch case), not published in the ECR, paragraph 112).

18 Therefore, the greater the designer’s freedom in developing a design, the less likely it is that minor differences between the designs at issue will be sufficient to produce different overall impressions on an informed user. Conversely, the more the designer’s freedom in developing a design is restricted, the more likely it is that minor differences between the designs at issue will be sufficient to produce different overall impressions on an informed user. Therefore, if the designer enjoys a high degree of freedom in developing a design, that reinforces the conclusion that designs that do not have significant differences produce the same overall impression on an informed user (Internal combustion engine, paragraph 17 above, paragraph 33, and Wristwatch case, paragraph 17 above, paragraph 113).

19 In the present case, the Board of Appeal rightly took the view that the freedom of the designer of armchairs is almost unlimited since armchairs can take any combination of colours, patterns, shapes and materials, and that the only limitation for the designer is the fact that armchairs have to be functional, that is, they must include at least a seat, a backrest and two armrests.

20 The applicant does not dispute the Board of Appeal’s findings concerning the definition and level of attention of the informed user or the designer’s degree of freedom. It takes issue with the Board of Appeal, however, for having found that the designs at issue produced different overall impressions.

21 In this connection, as regards the comparison of the overall impressions produced by the contested design and by the earlier design, the Board of Appeal found that the armchairs represented in the designs at issue both had a rectangular overall structure including rectangular frames as armrests and flat seats, that the armrests of the armchairs were on the same level as the upper limits of the backs of the armchairs and that the armrests of the armchairs were linked to the upper limit of the backs of the armchairs. It then observed that the designs at issue differed at least in the following respects: the frames of the armrests of the armchair represented in the earlier design were rectangles whereas those of the armchair represented in the contested design were squares; the backrest of the armchair represented in the earlier design was straight and vertical whereas that of the armchair represented in the contested design was inclined; in the earlier design, a noticeable gap separated the back of the armchair from the seat of the armchair whereas, in the contested design, the back of the armchair extended down to the seat; the armrests represented in the earlier design were broader than those represented in the contested design; the level of the seat of the armchair represented in the contested design was equidistant from the top and the bottom of the square that forms the armrest whereas in the earlier design the seat was considerably lower. The Board of Appeal also stated that the designs at issue differed, in addition, as to the number of plates composing the seat and the back of the armchairs and by the fact that the seat of the armchair represented in the contested design was slightly inclined. Lastly, it concluded that those differences were not insignificant and altered the appearance of the armchairs in a manner that would not go unnoticed by an observant user.

22 The applicant claims, in essence, that the designs at issue produce the same overall ‘cube’ impression and that the differences between them relate to immaterial details only.

23 In this connection, it must be observed, first, that it is true that in the designs at issue, the sides of the armchairs are formed of frames the upper part of which forms the armrests. Nevertheless, contrary to what the applicant claims, the frames composing the two sides of the armchair represented in the earlier design are not reproduced exactly in the contested design. As the Board of Appeal has pointed out, in the earlier design those frames are rectangles whereas in the contested design they are squares.

24 It is apparent from this that the rectangular frames give the armchair represented in the earlier design an elongated shape, whereas the armchair represented in the contested design is cube-shaped. The difference in the shape of the frames composing the sides of the armchairs gives them a different silhouette; the armchair represented in the earlier design is deeper than it is high.

25 Next, as the Board of Appeal has also observed, the level of the seat of the armchair represented in the contested design is positioned exactly at the mid-point of the frames forming the sides of the armchair, whereas in the earlier design, the seat of the armchair is positioned one third of the way up the frame starting from the bottom.

26 Lastly, having regard to the fact that the overall impression produced on the informed user by a design must necessarily be determined also in the light of the manner in which the product in question is used (Case T‑153/08 Shenzhen Taiden v OHIM – Bosch Security Systems (Communications equipment) [2010] ECR II‑2517, paragraph 66, and Case T‑68/10 Sphere Time v OHIM – Punch (Watch attached to a lanyard) [2011] ECR II‑2775, paragraph 78), account must be taken of the fact that the armchair represented in the earlier design has a low seat whereas that represented in the contested design has a higher seat. The informed user will perceive those differences as affecting how he will be seated, [and,] in particular, the position of his legs.

27 The effect of the difference in the shape of the frame (rectangle and square) and in the height of the seat is that the designs at issue differ in their proportions. The applicant is therefore wrong to claim that the designs at issue produce the same impression of a ‘perfect cube’.

28 Secondly, as the Board of Appeal has pointed out, the earlier design can be distinguished from the contested design by the open space between the seat and the back of the armchair. Therefore, the applicant cannot claim that the designs at issue share the same structure composed of a seat linked to the back [of the armchair].

29 Thirdly, as the Board of Appeal has stated, it is clear from the ‘in profile’ image of the contested design that the backrest of the armchair is inclined and that the seat is also slightly inclined. The applicant is therefore wrong to claim that the slant of the back of the armchair represented in the contested design is barely perceptible. By contrast, the back of the armchair represented in the earlier design is vertical and its seat is horizontal.

30 In view of the case-law cited in paragraph 26 above, according to which the overall impression produced on the informed user must necessarily be determined in the light of the manner in which the product in question is used, account must be taken of the difference between the designs at issue as regards the angle of the backrest and the seat of the armchair represented in the contested design. Since an inclined backrest and seat will give rise to a different [level of] comfort from that of a straight back and seat, the use that will be made of that armchair by the circumspect user is liable to be affected thereby.

31 Fourthly, as the Board of Appeal has observed, the designs at issue also differ in the number of plates that compose the seat of the armchairs. The seat of the armchair represented in the contested design is composed of a single plate, whereas that of the armchair represented in the earlier design is composed of three plates.

32 As regards the applicant’s argument that that difference is due to the addition of a cushion on the seat of the armchair represented in the contested design and that, underneath the cushion, the structure of the armchair also consists of several plates and is identical to that of the armchair represented in the earlier design, suffice it to point out that a part of a product represented in a design that is outside the user’s field of vision will have no great impact on how the design in question is perceived by that user (Wristwatch case, paragraph 17 above, paragraph 133).

33 Accordingly, the fact that, underneath the cushion, the seat of the armchair represented in the contested design is composed of plates is of little importance to the assessment of the overall impression produced on the informed user.

34 Furthermore, as the Board of Appeal has observed, a side view of the contested design indicates that, underneath the cushion, the seat of the armchair is composed of five plates. Even if that barely visible element fell to be taken into account, the contested design could be distinguished from the earlier design in which the seat of the armchair represented is composed of three plates.

35 Fifthly, as the Board of Appeal has observed, the frames composing the sides of the armchairs and, therefore, the armrests are of different thickness. The frames of the armchair represented in the earlier design are very thick and give it a more solid silhouette than that of the armchair represented in the contested design.

36 Lastly, the Board of Appeal’s finding that, taking account of their importance, the differences between the designs at issue would not escape the attention of an informed user, must be upheld.

37 It follows from the foregoing that the Board of Appeal was right to conclude that the designs at issue produced different overall impressions on the informed user and that the overall impression produced by the earlier design was not such as to deprive the contested design of its individual character within the meaning of Article 6 of Regulation No 6/2002.

38 That conclusion is not called in question by the applicant’s other arguments.

39 First, the applicant claims that, taking account of the very high degree of freedom of the designer, it is difficult to comprehend why the features of the contested design should be so similar to those of the earlier design, [the features of] which differentiate [the earlier design] from pre-existing armchair designs. The applicant submits that protection requires a creative effort that results in an object with an original and different appearance. The applicant claims, in essence, that the designer of the contested design reproduced the original idea of the earlier design, altering certain insignificant details only.

40 It is true, as the Board of Appeal has pointed out, that the possibilities for the design of an armchair are almost unlimited: the designer’s freedom may be applied to colours, patterns, shapes and materials. Nevertheless, it has been found, in paragraph 36 above, that the contested design differed from the earlier design, from the point of view of the informed user, in significant, not inconsiderable features concerning the appearance of the armchairs. The contested design cannot, therefore, be regarded as a reproduction of the earlier design or of the original idea that was developed for the first time in that earlier design.

41 Secondly, the applicant invokes two earlier OHIM decisions in which OHIM granted the applicant’s applications for a declaration that designs for armchairs registered by the intervener were invalid.

42 In this connection, it should be pointed out that the decision of the Invalidity Division and the decision of the Board of Appeal invoked by the applicant related to invalidity proceedings concerning designs other than the designs at issue in the present case and that the legality of the decisions of Boards of Appeal must be assessed solely on the basis of Regulation No 6/2002, as interpreted by the Courts of the European Union, and not on the basis of a previous decision-making practice of OHIM.

43 It follows from the foregoing that the single plea in law put forward by the applicant must be rejected and, consequently, the action must be dismissed in its entirety.

Costs

44 Under Article 87(2) of the Rules of Procedure of the General Court, the unsuccessful party is to be ordered to pay the costs if they have been applied for in the successful party’s pleadings.

45 Since the applicant has been unsuccessful, it must be ordered to pay the costs, in accordance with the form of order sought by OHIM and the intervener.

On those grounds,

THE GENERAL COURT (Seventh Chamber)

hereby:

1. Dismisses the action.

2. Orders Gandia Blasco, SA to pay the costs.

Van der Woude | Wiszniewska-Białecka | Ulloa Rubio |

Delivered in open court in Luxembourg on 4 February 2014.

[Signatures]