JUDGMENT OF THE GENERAL COURT (Sixth Chamber)

26 February 2014 (*)

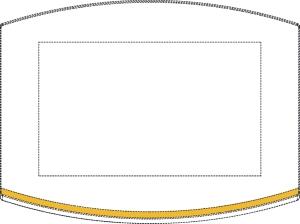

(Community trade mark — Application for a Community trade mark consisting of a representation of a yellow curve at the bottom edge of an electronic display unit — Absolute ground for refusal — Lack of distinctive character — Article 7(1)(b) of Council Regulation (EC) No 2007/2009)

In Case T‑331/12,

Sartorius Lab Instruments GmbH & Co. KG, established in Göttingen (Germany), represented by K. Welkerling, lawyer, given leave to replace Sartorius Weighing Technology GmbH,

applicant,

v

Office for Harmonisation in the Internal Market (Trade Marks and Designs) (OHIM), represented by G. Schneider, acting as Agent,

defendant,

ACTION brought against the decision of the First Board of Appeal of OHIM of 3 May 2012 (Case R 1783/2011-1), concerning an application for registration of a sign composed of a yellow curve at the bottom edge of an electronic display unit as a Community trademark,

THE GENERAL COURT (Sixth Chamber),

composed of S. Frimodt Nielsen, President, F. Dehousse and A. Collins (Rapporteur), Judges,

Registrar: E. Coulon,

having regard to the application lodged at the Court Registry on 27 July 2012,

having regard to the response of OHIM lodged at the Court Registry on 24 October 2012,

having regard to the order of 6 January 2014 allowing a substitution of parties,

in the absence of a request to fix a hearing submitted by the parties within a period of one month from notification of closure of the written procedure, and having therefore decided, upon a report of the Judge-Rapporteur and pursuant to Article 135a of the Rules of Procedure of the General Court, to rule without an oral procedure,

gives the following

Judgment

Background to the dispute

1 On 7 February 2011, Sartorius Weighing Technology GmbH, substituted under leave of the Court by the applicant, Sartorius Lab Instruments GmbH & Co. KG, filed an application for registration of a Community trade mark at the Office for Harmonisation in the Internal Market (Trade Marks and Designs) (OHIM) under Council Regulation (EC) No 207/2009 of 26 February 2009 on the Community trade mark (OJ 2009 L 78, p. 1).

2 The mark for which registration was sought, identified by Sartorius Weighing Technology as an ‘other’ mark, and depicting a yellow curve at the bottom edge of an electronic display unit, is reproduced below:

3 In the application for registration, the sign is described as follows:

‘The positional mark is composed of a yellow curve, open at the upper edge, placed at the lower edge of an electronic display unit and extending the entire width of the unit. The dotted outline of the edges is purely to show that the curve is affixed to an electronic screen and does not form part of the mark itself.’

4 The goods in respect of which registration was sought are in Classes 7 and 9 to 11 of the Nice Agreement concerning the International Classification of Goods and Services for the purposes of Registration of Marks of 15 June 1957, as revised and amended, and correspond, for each of those classes, to the following descriptions:

– Class 7: ‘Chemical industry machinery; machines for the food and beverage industry; mixing machines; agitators (machines); vibrators for industrial purposes; electric welding machines; centrifuges; centrifugation chambers; all the aforesaid goods fitted with electronic display units’;

– Class 9: ‘Scientific instruments and apparatus, including laboratory apparatus; weighing apparatus and instruments and parts therefor; electronic testing apparatus for air and liquid filters; measuring and checking apparatus and parts therefor, optical measuring, signalling and checking (supervision) apparatus and instruments, in particular microscopes, gas testing equipment, spectrometers, including fluorescence spectra and nephelometry apparatus; probes for scientific purposes, in particular sensors, collecting and filtering apparatus for airborne germs and parts therefor; apparatus, combinations of apparatus and their parts for physical or chemical analysis; thermostats; data-processing apparatus, in particular apparatus for the logging, storage, reproduction and/or control of data, including for chemical change processes; fermenters and bioreactors; temperature control apparatus for chilling biopharmaceutical materials in disposable containers; apparatus for welding and separating plastics, apparatus for the sterile connection of plastic vessels, such as plastic pipes, tubes, sachets and containers, electric welding apparatus, in particular for plastic flexible tubing; apparatus for breeding cell cultures (not for medical purposes); laboratory apparatus for cultivating, incubating, dyeing and analysing biological materials including microorganisms, cells and tissue; laboratory shakers; platforms for laboratory shakers, in particular fitted with measuring stations for logging physical data and/or with data interfaces for exchanging data with external apparatus; laboratory centrifuges; laboratory centrifugation chambers; apparatus for mixing biopharmaceutical media, in particular by vibration, rotation and wave motion; electric metal-detecting equipment; all the aforesaid goods fitted with electronic display units’;

– Class 10: ‘Medical apparatus and instruments; all the aforesaid goods fitted with electronic display units’;

– Class 11: ‘Apparatus and installations for the treatment of water and the treatment of solutions in the pharmaceutical, medical and laboratory fields, equipment for de-ionising water and purifying water and the parts therefor; equipment for de-pyrogenising solutions and for separating harmful substances from fluids; filtration installations for environmental engineering and for the food and drinks industry; all the aforesaid goods fitted with electronic display units’.

5 By decision of 28 July 2011, the examiner refused the trade mark application, in respect of all the goods referred to in paragraph 4 above, pursuant to Article 7(1)(b) of Regulation No 207/2009, on the ground that the mark applied for lacked distinctive character in relation to those goods.

6 On 26 August 2011, Sartorius Weighing Technology appealed against the examiner’s decision under Articles 58 to 64 of Regulation No 207/2009.

7 By decision of 3 May 2012 (‘the contested decision’), the First Board of Appeal of OHIM dismissed the appeal on the ground that the mark applied for was devoid of any distinctive character within the meaning of Article 7(1)(b) of Regulation No 207/2009. In essence, the Board found that the object of the application for registration was composed of a yellow curve, open at the upper edge, and placed at the lower edge of an electronic display unit. The Board found that all the goods affected by the trademark application were equipped with an electronic display unit and that the relevant public, namely professionals in special technical and industrial fields, would perceive the sign as a simple screen decoration. The Board held that the form depicted did not communicate any information about the product manufacturer. Therefore, it concluded that the said sign did not have the required minimum distinctive character to constitute a Community trademark.

Forms of order sought by the parties

8 The applicant claims that the Court should:

– annul the contested decision;

– order OHIM to pay the costs of these proceedings together with the costs of the preceding appeal procedure.

9 OHIM contends that the Court should:

– dismiss the action;

– order the applicant to pay the costs.

Law

10 In support of its appeal, the applicant raises a single plea in law, alleging infringement of Article 7(1)(b) of Regulation No 207/2009.

11 The applicant, in contrast to the Board of Appeal, considers that the sign applied for would not be perceived by the relevant public exclusively as a decorative element, but as an original sign having a sufficiently distinctive character in order to constitute a trademark.

12 OHIM contests the applicant’s arguments.

13 The applicant describes the sign applied for as a ‘positional mark’. In that regard, it should be noted that neither Regulation No 207/2009 nor Commission Regulation (EC) No 2868/95 of 13 December 1995 implementing Council Regulation (EC) No 40/94 on the Community trade mark (OJ 1995 L 303, p. 1) refers to ‘positional marks’ as a specific category of marks. However, in so far as Article 4 of Regulation No 207/2009 does not contain an exhaustive list of signs capable of being Community trade marks, that circumstance is without relevance to the registrability of ‘positional marks’.

14 In addition, it appears that ‘positional marks’ are similar to the categories of figurative and three-dimensional marks, since they concern figurative or three-dimensional elements that are applied to the surface of a product. The applicant does not seek to describe the said sign as a figurative sign, whether three-dimensional or other.

15 Nonetheless, the classification of a ‘positional mark’ as a figurative or three-dimensional mark is irrelevant for the purpose of assessing its distinctive character (Case T‑547/08 X Technology v OHIM (Orange colouring of the toe of a sock) [2010] ECR II‑2409, paragraphs 19 to 21).

16 Under Article 7(1)(b) of Regulation No 207/2009, trade marks which are devoid of any distinctive character may not be registered.

17 According to settled case-law, for the purposes of that article the mark must serve to identify the product in respect of which registration is sought as originating from a particular undertaking, and thus to distinguish that product from those of other undertakings (Joined Cases C‑473/01 P and C‑474/01 P Procter & Gamble v OHIM [2004] ECR I‑5173, paragraph 32, and Case C‑64/02 P OHIM v Erpo Möbelwerk [2004] ECR I‑10031, paragraph 42).

18 That distinctive character must be assessed, first, by reference to the goods or services in respect of which registration is sought and, second, by reference to the perception that the relevant public has of those goods and services (see Procter & Gamble v OHIM, cited at paragraph 17 above, paragraph 33, and Case C‑25/05 P Storck v OHIM [2006] ECR I‑5719, paragraph 25).

19 A minimum degree of distinctive character is, however, sufficient to render the absolute ground for refusal set out in Article 7(1)(b) of Regulation No 207/2009 inapplicable (Case T‑337/99 Henkel v OHIM (Round red and white tablet) [2001] ECR II‑2597, paragraph 44, and Case T‑139/08 The Smiley Company v OHIM (Representation of half a smiley smile) [2009] ECR II‑3535, paragraph 16).

20 The perception of the relevant public is, however, liable to be influenced by the nature of the sign in respect of which registration is sought. Therefore, to the extent to which average consumers are not in the habit of making assumptions as to the commercial origin of goods on the basis of signs which are indistinguishable from the appearance of the goods themselves, such signs will be distinctive, within the meaning of Article 7(1)(b) of Regulation No 207/2009, only if they depart significantly from the norm or customs of the sector (see, to that effect, Case C‑136/02 P Mag Instrument v OHIM [2004] ECR I‑9165, paragraphs 30 and 31; Case C‑173/04 P Deutsche SiSi-Werke v OHIM [2006] ECR I‑551, paragraphs 28 and 31; and Case C‑144/06 P Henkel v OHIM [2007] ECR I‑8109, paragraphs 36 and 37).

21 The decisive factor governing the applicability of the case-law cited in paragraph 20 above is not the classification of the sign as figurative, three-dimensional or other, but the fact that the sign is indistinguishable from the appearance of the product in question. Thus, that criterion has been applied, not only to three-dimensional marks (Procter & Gamble v OHIM, cited at paragraph 17 above; Mag Instrument v OHIM, cited at paragraph 20 above; and Deutsche SiSi-Werke v OHIM, cited at paragraph 20 above), but also to figurative marks consisting of a two-dimensional representation of the product in question (Storck v OHIM, cited at paragraph 18 above, and Henkel v OHIM, cited at paragraph 20 above), and also to a sign consisting of a design applied to the surface of the product (Order in Case C‑445/02 P Glaverbel v OHIM [2004] ECR I‑6267). Likewise, according to case-law, colours and abstract combinations thereof cannot be regarded as intrinsically distinctive save in exceptional circumstances, since these are indistinguishable from the appearance of the goods designated and are not, in principle, used as a means of identifying commercial origin (see, by analogy, Case C‑104/01 Libertel [2003] ECR I‑3793, paragraphs 65 and 66, and Case C‑49/02 Heidelberger Bauchemie [2004] ECR I‑6129, paragraph 39).

22 In those circumstances, it is necessary to determine whether the mark applied for is indistinguishable from the appearance of the product designated or whether, on the contrary, it departs significantly from the norm and customs of the relevant sector.

23 According to the information provided by the applicant, namely at paragraphs 3.2.1 and 3.2.2 of the application, the mark applied for is intended to protect a specific sign placed on a particular area of the lower edge of the designated measuring instruments, at the bottom of their electronic display units. Thus, even though it is clear that the outlines of the display unit represented in the drawing reproduced at paragraph 2 above do not form part of the mark sought, which consists of a yellow curve, the curve cannot be dissociated from the shape of a part of the goods designated by the mark applied for. As OHIM rightly observes, the curve that the mark applied for is intended to protect will vary according to the shape of each designated product, by following its contour. Accordingly, the view must be taken that the mark applied for is indistinguishable from the appearance of the designated product and that, consequently, the case-law cited in paragraph 20 above is applicable (see, to that effect, judgment of 14 September 2009 in Case T‑152/07 Lange Uhren v OHIM (Geometric shapes on a watch face), not published in the ECR, paragraphs 79 to 83). The applicant can therefore not object to the Board of Appeal relying on that case-law in the contested decision.

24 In the present case, the applicant does not dispute the Board of Appeal’s assessment that the goods in question are special technical products aimed at professionals.

25 On the other hand, the applicant disputes the Board of Appeal’s assessment that the relevant public pays a ‘medium to high level of attention’ to the goods designated by the mark applied for. In the first part of its plea, the applicant maintains that the level of attention paid by the relevant public is very high. It objects to the Board of Appeal not following the examiner’s finding in that regard, a finding that was not disputed by the parties.

26 In this respect, it should be remembered that, under Article 64(1) of Regulation No 207/2009, following the examination as to the merits of the appeal, the Board of Appeal is to decide on the appeal and, in doing so, may exercise any power within the competence of the authority responsible for the decision appealed against. It follows from that provision that, through the effect of the appeal against an examiner’s decision refusing registration, the Board of Appeal may carry out a new and full examination of the merits of the application for registration, in terms of both law and fact, that is to say, in the present case, itself decide on the application for registration by either rejecting it or declaring it to be founded, thereby either upholding or reversing the decision appealed against (see, to that effect, Case C‑29/05 P OHIM v Kaul [2007] ECR I‑2213, paragraphs 56 and 57).

27 The Board of Appeal was therefore able to exercise the powers of the examiner and to rule on the appeal by determining, as it did in paragraphs 12 to 14 of the contested decision, the relevant public and its level of attentiveness towards the goods in question. The same goes for its assessment of the distinctive nature of the mark applied for.

28 At paragraph 14 of the contested decision, the Board of Appeal held that the mark application essentially affected machines for industrial applications contained in Class 7, apparatus, principally for scientific use, in Class 9, medical instruments and apparatus in Class 10, and apparatus and installations for the treatment of water and treatment of solutions in the pharmaceutical, medical and laboratory fields and filtration installations for environmental engineering and for the food and drinks industry in Class 11. The Board then held that these were special technical products aimed at professionals who paid them a medium to high level of attention.

29 Therefore, the Board of Appeal did not err in holding, at paragraph 15 of the contested decision, that, in the case of marks which, like the sign in question, are not independent of the goods which they designate, only a mark that significantly departs from the norm or customs of the sector is not devoid of distinctive character for the purposes of Article 7(1)(b) of Regulation No 207/2009. Consequently, the Board of Appeal applied the case-law cited at paragraphs 20 and 21 above to consumers in the specific sector relevant to the mark applied for and not, as the applicant claims, to the average consumer in general.

30 The applicant does not, moreover, dispute the Board of Appeal’s assessment, at paragraph 17 of the contested decision, that all the products affected by the mark application are fitted with electronic display units. Therefore, the Board of Appeal was right to base its reasoning at paragraph 18 of the contested decision on facts resulting from ‘general practical experience of electronic display units on technical instruments, which are likely to be familiar to anybody and which, moreover, are particularly familiar to consumers of these products’. It is therefore necessary to reject the applicant’s argument that the Board of Appeal did not take into account the relevant public’s ‘prior knowledge or expectations’ or its ‘habits’.

31 Contrary to the applicant’s claim, the Board was correct thus to take into consideration facts which are likely to be known by anyone or which may be learnt from generally accessible sources (Case T‑185/02 Ruiz-Picasso and Others v OHIM (DaimlerChrysler (PICARO)) [2004] ECR II‑1739, paragraphs 28 and 29, and judgment of 13 June 2012 in Case T‑542/10 XXXLutz Marken v OHIM (Meyer Manufacturing (CIRCON)), not published in the ECR, paragraph 38).

32 The applicant has failed to supply any evidence to challenge the assessment that the professionals making up the relevant public pay a medium to high level of attention to the goods in question. Indeed, the applicant merely refers firstly to the arguments contained in its own pleadings produced during the OHIM proceedings and, secondly, to Annexes A.6 to A.14 of the application. The said annexes contain brochures for products allegedly similar to the goods in question, but the applicant gives no indication of how these brochures might prove that ‘the relevant public therefore consists of interested specialists who are much better informed than average and who will be struck by the tiniest detail of the presentation of the goods concerned’. Therefore, the first part of the applicant’s single plea must be rejected.

33 For the sake of completeness, it should be pointed out that these brochures, including the applicant’s own contained in Annex A.14, set out the technical specifications for the products in question, generally in the form of a table, which would suggest that consumers — assuming that their level of attentiveness is very high, as claimed by the applicant — rely on these technical details rather than on physical appearance when they purchase such products.

34 In the second part of its plea, the applicant disputes the Board of Appeal’s assessment in relation to the distinctive character of the mark applied for.

35 It should be remembered that, where an applicant claims that a trade mark applied for is distinctive, notwithstanding OHIM’s analysis, it is for that applicant to provide specific and substantiated information to show that the trade mark applied for has an intrinsic distinctive character (Case C‑283/06 P, Develey v OHIM [2007] ECR I‑9375, paragraph 50).

36 It is apparent from the description of the sign applied for, at paragraph 3 above, that the sign consists of a yellow curve open at the upper edge and placed at the lower edge of an electronic display unit in a precise location. The Board of Appeal was therefore correct in saying, and this was not contested by the applicant, that the sign was not independent of the appearance of the goods designated.

37 The Board of Appeal found that the placing of a curve on the lower edge of an electronic display unit was, in the view of consumers of the goods in question, a simple screen decoration. Consumers would not perceive this particularly simple decoration as an indication of the origin of the goods. The Board of Appeal stated that, despite the fact that a consumer would not generally pay any attention, or only minimal attention, to the aesthetic aspect of electronic display units, there was nothing to indicate that products meant for industrial purposes generally had no aesthetic quality.

38 That analysis by the Board of Appeal must be endorsed. It should be noted that, even if instruments within the remit of the mark applied for are generally of sober appearance, they are not entirely devoid of aesthetic qualities. Indeed, it is apparent from Annexes A.6 to A.14 to the application that it is not unusual to include an element of colour around the screen of such instruments, either on the buttons at the side of the display unit, or by way of bright colour on the surround of the display itself. In particular, one manufacturer, whose brochure appears at Annex A.12, places four bright yellow curved lines across the screen. Unlike the applicant, the other manufacturers whose brochures are annexed to the application include their name on the screen of their products. Consumers are therefore used to seeing colourful motifs on apparatus within the scope of the mark applied for. They will therefore perceive them to be a decorative element and not the indication of the commercial origin of the goods, especially since, generally speaking, manufacturers place their names on products to indicate their origin.

39 The sign applied for consists of a simple motif. Although it is brightly coloured, it does not contain any striking element that of itself attracts the attention of the relevant public, even if the relevant public can be considered to possess a high level of attentiveness. It thus follows from paragraph 38 above, contrary to the applicant’s claims, that it is not unusual, in the sector in question, to include such a ‘visual indication’ of colour around the screen of the apparatus. In addition, the applicant does not assert that any particular shade of yellow appertains to the mark applied for. It must therefore be held that the mark applied for does not possess any unique, original or unusual character.

40 The fact that the applicant has not raised any technical or functional impact of the positioning of the sign applied for does not alter this assessment. In order to have the minimum degree of distinctiveness required under Article 7(1)(b) of Regulation No 207/2009, the mark applied for must simply appear prima facie capable of enabling the relevant public to identify the origin of the goods or services covered by the Community trade mark application and to distinguish them, without any possibility of confusion, from those of a different origin (Case T‑441/05 IVG Immobilien v OHIM (I) [2007] ECR II‑1937, paragraph 55). That is not the position in the present case. The mark applied for does not have any characteristic element, nor any memorable or eye-catching features likely to lend it a minimum degree of distinctiveness and enable the consumer to perceive it otherwise than as a decoration typical of goods in Classes 7 and 9 to 11.

41 Accordingly, the mere fact that other marks, although equally simple, have been regarded as being capable of indicating the origin of the relevant products and, therefore, as not being devoid of any distinctive character, is not conclusive for the purpose of establishing whether the mark at issue also has the minimum degree of distinctiveness necessary for registration (see to that effect, Representation of half a smiley smile, cited at paragraph 19 above, paragraph 34). It is possible for a mark to acquire a distinctive character through use over time, but the applicant has not put forward any argument on the basis of Article 7(3) of Regulation No 207/2009 in the present case.

42 Consequently, it must be held that the Board of Appeal did not err in finding that, by reason of the absence of any significant divergence from the norms or customs of the sector in question, the mark applied for would be perceived by the relevant public as a decorative element and that it was, for that reason, devoid of any distinctive character for the purposes of Article 7(1)(b) of Regulation No 207/2009. The second part of the single plea must therefore be rejected.

43 As the two parts of the single plea in law have been rejected, that plea must be rejected and the action consequently dismissed in its entirety.

Costs

44 Under Article 87(2) of the Rules of Procedure of the General Court, the unsuccessful party is to be ordered to pay the costs if these have been applied for in the successful party’s pleadings. Since the applicant has been unsuccessful, it must be ordered to pay OHIM’s costs, in accordance with the form of order sought by OHIM.

On those grounds,

THE GENERAL COURT (Sixth Chamber)

hereby:

1. Dismisses the action;

2. Orders Sartorius Lab Instruments GmbH & Co. KG to pay the costs.

Frimodt Nielsen | Dehousse | Collins |

Delivered in open court in Luxembourg on 26 February 2014.

[Signatures]