JUDGMENT OF THE COURT OF FIRST INSTANCE (Third Chamber)

12 March 2008 (*)

(Public service contracts – Community tendering procedure – Provision of services for the development and provision of services in support of the Community Research and Development Service (CORDIS) – Rejection of a tender – Principles of equal treatment as between tenderers and transparency)

In Case T‑345/03,

Evropaïki Dynamiki – Proigmena Systimata Tilepikoinonion Pliroforikis kai Tilematikis AE, established in Athens (Greece), represented initially by S. Pappas and subsequently by N. Korogiannakis, lawyers,

applicant,

v

Commission of the European Communities, represented by C. O’Reilly and L. Parpala, acting as Agents,

defendant,

APPLICATION for the annulment of the decision to award the contract which is the subject of the Commission’s call for tenders ENTR/02/55 – CORDIS Lot 2 for the development and provision of services in support of the Community Research and Development Service (CORDIS),

THE COURT OF FIRST INSTANCEOF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES (Third Chamber),

composed of M. Jaeger, President, J. Azizi and E. Cremona, Judges,

Registrar: C. Kristensen, Administrator,

having regard to the written procedure and further to the hearing on 13 July 2006,

gives the following

Judgment

Legal context

1 Until 31 December 2002, the award of public service contracts by the Commission was governed by the provisions of Section 1 (Articles 56 to 64 bis) of Title IV of the Financial Regulation of 21 December 1977 applicable to the general budget of the European Communities (OJ 1977 L 356, p. 1), as amended by Council Regulation (EC, ECSC, Euratom) No 2673/99 of 13 December 1999 (OJ 1999 L 326, p. 1), which came into force on 1 January 2000 (‘the Financial Regulation’).

2 According to Article 56 of the Financial Regulation:

‘When concluding contracts for which the amount involved is equal to or greater than the threshold provided for by the Council directives on the coordination of procedures for the award of public works, supplies and service contracts, each institution shall comply with the same obligations as are imposed upon bodies in the Member States by those directives.

The implementing measures provided for in Article 139 shall include appropriate provisions to that end.’

3 Article 139 of the Financial Regulation provides as follows:

‘In consultation with the European Parliament and the Council and after the other institutions have delivered their opinions, the Commission shall adopt implementing measures for this Financial Regulation.’

4 Pursuant to Article 139 of the Financial Regulation, the Commission adopted Regulation (Euratom, ECSC, EC) No 3418/93 of 9 December 1993 laying down detailed rules for the implementation of certain provisions of the Financial Regulation (OJ 1993 L 315, p. 1) (‘the Implementing Rules’). Articles 97 to 105 and 126 to 129 of the Implementing Rules apply to the award of public service contracts.

5 In particular, Article 126 of the Implementing Rules provides as follows:

‘The Council directives on public works, supplies and services shall be applicable to the award of contracts by the institutions whenever the amounts involved are equal to or greater than the amounts provided for in those directives.’

6 Article 3(2) of Council Directive 92/50/EEC of 18 June 1992 relating to the coordination of procedures for the award of public service contracts (OJ 1992 L 209, p. 1), as amended by Directive 97/52/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 October 1997, also amending Directives 93/36/EEC and 93/37/EEC concerning the coordination of procedures for the award of public supply contracts and public works contracts respectively (OJ 1997 L 328, p. 1), provides as follows:

‘Contracting authorities shall ensure that there is no discrimination between different service providers.’

Background to the dispute

I – CORDIS

7 The present case concerns the general call for tenders ENTR/02/55 relating to the development and provision of the new version of services in support of the Community Research and Development Information Service (CORDIS) (‘the call for tenders at issue’). CORDIS is an informatics tool which enables framework programmes for European research to be implemented. It is the principal publishing and communication service for prospective or existing participants and for other groups with an interest in a framework programme for European research. It consists of a multi-purpose platform which can be adapted to the user’s needs, a portal for those involved in European research and innovation and a tool for the dissemination of information to the public.

8 As of 1998, all the support services for CORDIS were supplied by a single contractor, namely Intrasoft International SA (‘the existing contractor’).

9 The adoption of the Sixth Framework Programme of the European Community for research, technological development and demonstration activities contributing to the creation of the European Research Area and to innovation (2002-2006) by Decision No 1513/2002/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 June 2002 (OJ 2002 L 232, p. 1) marked the beginning of a new phase in the implementation of CORDIS. For that new phase, the Commission decided to launch a call for tenders and to divide the project in question in the present case into five lots.

II – The call for tenders at issue, the successful tenderer and the award of the contested contract

10 On 13 February 2002, the prior information notice for the invitation to tender at issue was published in the Supplement to the Official Journal of the European Communities (OJ S 31). A prior information notice modifying it was published in the Supplement to the Official Journal of the European Communities of 7 August 2002 (OJ S 152).

11 On 20 November 2002, the contract notice for Lots 1 to 3 was published in the Supplement to the Official Journal of the European Communities (OJ S 225).

12 Volume A of the tendering specifications for the call for tenders at issue, entitled ‘the general part’, (‘Volume A of the tendering specifications’) states, inter alia, as follows:

‘Preamble

This is Volume A, the general part of the tendering specifications, applicable to all 5 lots.

For the specific parts, please refer to:

…

Lot 2 – Development

(development and maintenance of the technical infrastructure of all services)

…

1.3 Start date and duration of the contract

The contracts are expected to be signed in June 2003 and to start on the 1st of July 2003.

The first three months of the contracts are the “running-in phase” of the contracts.

Running-in serves the purpose to enable [sic] non-incumbent contractors to familiarise [themselves] with the CORDIS service. The previous contract specifies a “handover”. New contractors will thus be able to access the service operations in order to prepare themselves for takeover of the services … [at] the latest by the end of the running-in phase.

The running-in is not paid [sic].

It is not excluded, subject to the approval of the CPO and subject to the agreement of the existing contractor, that parts or all of the service are already taken over during the running-in phase (for payment of services taken over during the running-in phase, see point 1.7).

…

1.7 Payment

Payment for each lot shall be made within the delay [sic] fixed by the Commission’s internal regulations for payment as follows:

…

– in [the] case that parts or all of the service are taken over by the new Contractor during the running-in phase (see 1.3), the new Contractor will be paid as of the date of successful takeover for the parts of the service taken over; …

…

3.3 Evaluation of offers – award criteria

The contract will be awarded to the most cost-effective offer (“best value for money”), on the basis of the following award criteria:

– the qualitative award criteria

– the price

The first step in the assessment procedure is to evaluate the selected tender(s) according to the following qualitative award criteria and the corresponding weighting of each criterion.

Criterion | Qualitative award criteria | Weighting (max. points) for Lots 1, 2, 4, 5 | Weighting (max. points) for Lot 3 |

1 | Technical merit, conformity with the technical terms of reference and how these are addressed; proposed technical approach (functional completeness, compliance with technical requirements, appropriateness of proposed technology) | 35 | … |

2 | Quality of proposed methodology (working methods aiming at effectiveness, usability, security and confidentiality; service reliability / availability / recovery / maintenance; adopting best practices) | 25 | … |

3 | Creativity, degree of innovation (value of original ideas on how to innovate the service) | 20 | … |

4 | Quality of proposed schedule, contract management and control (proposed arrangements for the production of deliverables on time, and to ensure that the objectives and deadlines are met and quality is guaranteed) | 20 | … |

5 … (only for Lot 3) | … | … | … |

| | Total points | 100 | … |

…

4. Technical specifications

Executive summary

There could be up to five independent Contractors to run the CORDIS service. These are specialising [sic] in the following way:

…

Lot 2 will assure [sic] the development of the technical infrastructure used by the other lots and the Commission, such as the Common Production System (CPS), the Web Content Management System (WCMS), the Information Dissemination System (IDS) with all its components (WWW server(s), FTP server(s), BBS, eMail server, firewall, LAN, WAN, broadband Internet access, etc.). Lot 2 will also develop new tools and features, some of which [are] for experimental purposes(s). Lot 2 will bring the know-how and the service-application software, whereas each other lot – and the Commission – will provide the underlying building blocks, i.e. hardware and software system(s), like [sic] database management system, router etc.

…’

13 Volume B of the tendering specifications for the call for tenders at issue, entitled ‘Lot 2 Development’ (‘Volume B of the tendering specifications’) sets out the specifications for Lot 2. It provides, inter alia, as follows:

‘6.2.1 Technical and functional evolution of the system architecture and processes

…

The following specifications – on the basis of the current state of CORDIS as of June 2002 and the predictable near future – concentrate on describing objectives and basic requirements of what is needed for the continuation and evolution of CORDIS. As far as the how is concerned, only minimal requirements are set out in these specifications. The Tenderer/Contractor will provide full information on how those requirements will be met.

…

6.2.3.3 Indexing, Specific Views and Taxonomies

The ability to present content using predefined profiles to reach targeted user communities and constituencies. Advanced meta-structure and tagging techniques would need to be applied to content objects. There exists the possibility to make use of available products to implement, for example, taxonomy building, but these should have long-term application and be consistent [compatible] with the CORDIS architecture.

…

6.8 Hand-over to the next Contractor

The Contractor will hand over to the next Contractor – respectively to the Commission, where the latter requests for them [sic] – all relevant objects, like [sic] requirements and design specifications, release plans, source code, procedures, test plans, migration plans, results, including full documentation in whatsoever form (paper and electronic). Also, the product licences, which have been acquired and/or taken over from the previous Contractor(s), will be orderly transferred [sic] to the next Contractor or to the Commission.’

14 On the same day, the Commission provided the prospective tenderers with a CD‑ROM containing information on the computer equipment and the software in use at that time (‘CD 1’).

15 On 20 December 2002, the Commission provided the prospective tenderers with a second CD-ROM containing additional technical information (‘CD 2’).

16 At the end of December 2002, the Commission acquired a software product known as ‘Autonomy’, which is a contextual search tool enabling the final users of CORDIS to carry out targeted searches in the CORDIS data bases as well as multilingual terminological searches.

17 On 7 January 2003, an information day open to all prospective tenderers was organised by the Commission, as provided for in point 1.6 of Volume A of the tendering specifications.

18 On 5 February 2003, the Commission published on a temporary website specifically dedicated to the call for tenders at issue a list reiterating all the existing computer equipment and all the software in use at that time (‘the asset list’).

19 On 18 February 2003, the Commission also published on that site a document entitled ‘Superquest – Implementation of Release 6 and beyond’. That document, which is dated 6 February 2003 and is called a ‘draft’, was drawn up by the existing contractor. It contained technical specifications for implementing the Autonomy software as well as a recommendation to acquire it.

20 On 9 March 2003, the applicant, Evropaïki Dynamiki – Proigmena Systimata Tilepikoinonion Pliroforikis kai Tilematikis AE, in consortium with a Belgian company, submitted a tender for Lot 2 of the project (‘the contested contract’).

21 The deadline for the submission of tenders laid down in the tendering specifications was set for 19 March 2003.

22 The tenders were opened on 26 March and 1 April 2003.

23 The Evaluation Committee met on several occasions between 27 March and 19 June 2003.

24 On 19 June 2003, the Evaluation Committee produced a report which included, inter alia, as regards the applicant’s tender, the following comments:

Criteria | Comments | Points |

1. Technical merit, conformity with the technical terms of reference … | Proposed technical platform based on J2EE (following FP6, eEurope etc), based on top of NCA but little detail on how NCA will be developed and maintained. Good generic justification of J2EE and associated benefits. WCMS proposal dependent on EC choice; assumes functions delivered by chosen WCMS. Search etc functionality assumptions based on Autonomy, mostly descriptive and including material copied from CORDIS Release 6 user requirements available from CFT2002 website. … … Generally, the understanding of the requirements and the necessary technology is well covered and encourages high marks. However, there is too much unnecessary detail and redundant material and a lack of concrete proposals. Too many ‘will be considered’ and ‘solutions will be provided’ with no substance. | 21.6/35 |

2. Quality of proposed methodology … | … … … Good but generic mention of design patterns and software reuse. … … | 14.8/25 |

3. Creativity, degree of innovation … | … … … | 12.8/20 |

4. Quality of proposed schedule, contract management and control … | … … … … … … | 12.8/20 |

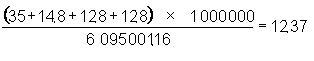

25 The Evaluation Committee finally proposed that the tender of the Belgian company Trasys should be accepted for the contested contract. It based its decision on the results of a qualitative and financial evaluation of the applicant and Trasys, which were set out as follows:

Name | Qualitative award criteria / points | |

| | 1 (35) | 2 (25) | 3 (20) | 4 (20) | Total (100) |

Applicant | 21.6 | 14.8 | 12.8 | 12.8 | 62.0 |

Trasys | 25.6 | 16.2 | 14.0 | 13.8 | 69.6 |

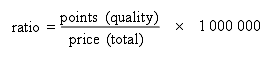

Name | Total price (€) | Points – quality | Ratio – Value for money |

Applicant | 6 095 001.16 | 62.0 | 10.17 |

Trasys | 5 543 392.07 | 69.6 | 12.56 |

26 On 6 July 2003, the Commission decided to accept the Evaluation Committee’s recommendation and to award the contested contract to Trasys (‘the successful tenderer’). The successful tenderer stated in its tender that, subject to how the work under the contested contract progressed, at least 35% of it would be subcontracted to the existing contractor.

27 By letter of 1 August 2003, the Commission informed the applicant that its tender had not been accepted.

Procedure and forms of order sought by the parties

28 The applicant brought the present action by application lodged at the Registry of the Court of First Instance on 30 September 2003.

29 The applicant claims that the Court should:

– annul the decision of the Commission to evaluate its tender as unsatisfactory;

– order the Commission to re-evaluate its tender;

– order the Commission to pay the costs.

30 The defendant contends that the Court should:

– dismiss the application;

– order the applicant to pay the costs.

31 By letter lodged at the Court Registry on 16 September 2004, the applicant sought leave to reply to the rejoinder in writing.

32 On 26 October 2004, the Court informed the applicant of its decision to refuse such leave.

33 Upon hearing the report of the Judge-Rapporteur, the Court of First Instance decided to open the oral procedure and, by way of measures of organisation of procedure provided for by Article 64 of its Rules of Procedure, it requested the parties, by letter of 20 June 2006, to reply in writing to additional questions.

34 By letters lodged at the Court Registry on 30 June 2006, the parties replied to the written questions of the Court.

35 The parties presented oral argument and answered the questions put to them by the Court at the hearing on 13 July 2006.

36 By letter of 24 July 2006, the applicant provided additional explanations of its oral submissions.

37 On 14 September 2006, the Court decided to reopen the oral procedure.

38 By letters of 15 September 2006, the Court requested the applicant to produce in writing the calculation which it had carried out in the course of the hearing and to explain each of its separate stages.

39 The applicant replied to that request by letter lodged on 26 September 2006.

40 By letter lodged on 22 November 2006, the Commission set out its observations on the applicant’s written response.

41 On 6 December 2006, the Court decided to close the oral procedure.

Law

I – Scope of the application for annulment

42 By the first head of claim in its application, the applicant seeks annulment of the Commission’s decision to evaluate its tender as unsatisfactory. By its second head of claim, the applicant seeks an order that the Commission re-evaluate its tender.

43 As regards the first head of claim, it must be noted that the Commission did not decide that the applicant’s tender was unsatisfactory.

44 Moreover, by writing on the copy of the decision to award the contested contract which was submitted to the Court as an annex to the application the words ‘contested measure’, the applicant itself indicated that it considered that measure to be the subject of its application for annulment.

45 As a consequence, the first head of claim seeks annulment of the decision to award the contested contract to a tenderer other than the applicant, whose tender was considered to be better (‘the contested decision’).

46 As regards the second head of claim, it is settled case-law that the Community judicature is not entitled, when exercising judicial review of legality, to issue directions to the institutions; rather, it is for the administration concerned to adopt the necessary measures to implement a judgment given in proceedings for annulment (Case T-67/94 Ladbroke Racing v Commission [1998] ECR II-1, paragraph 200, and Joined Cases T-374/94, T-375/94, T‑384/94 and T‑388/94 EuropeanNight Services and Others v Commission [1998] ECR II‑3141, paragraph 53).

47 Accordingly, the applicant’s second head of claim must be rejected as inadmissible in so far as it seeks an order that directions be issued to the Commission.

II – The application for annulment of the contested decision

A – Pleas in law

48 In support of its action for annulment, the applicant puts forward four pleas in law, which are divided into a number of parts.

49 By its first plea, the applicant submits that the Commission failed, first, to communicate the information requested by the applicant and, second, to give sufficient reasons for its decisions. In particular, first of all, it considers that the Commission responded to a request for information made during the tendering procedure only after the closing date for submitting tenders. Secondly, the applicant considers that the Commission failed to provide it with full extracts of an alleged favourable recommendation made to the Advisory Committee on Procurement and Contracts in respect of its tender and that of the successful tenderer. Thirdly, the applicant considers that the Commission failed to make available to it information on the names of the successful tenderer’s subcontractors. Fourthly, the applicant claims that an additional committee, not provided for in the Implementing Rules, participated in the evaluation of the tenders. By its second plea, the applicant submits that the Commission infringed the principle of equal treatment as between tenderers laid down in Article 126 of the Implementing Rules and in Article 3(2) of Directive 92/50, first of all, by laying down a requirement in the tendering specifications for an unpaid running-in phase and, secondly, by failing to make available to all prospective tenderers various relevant technical information from the beginning of the tendering procedure. By its third plea, the applicant maintains that the Commission committed manifest errors in the assessment of its tender and in the assessment of the successful tenderer’s tender. Lastly, in its reply, the applicant submits that the Commission failed to define clear and objective evaluation rules for the call for tenders at issue.

50 The Court considers that it is appropriate to examine at the outset the second plea since the applicant claims that the principle of equal treatment as between tenderers was infringed from the beginning of the tendering procedure.

B – The second plea, alleging infringement of the principle of equal treatment as between tenderers

51 The second plea is based, first, on the requirement for an unpaid three-month running-in phase and, second, on the lack of access to certain technical information.

1. The first part of the second plea, concerning the requirement for an unpaid three-month running-in phase

a) Arguments of the parties

52 The applicant submits that the Commission infringed the general prohibition of discrimination as between tenderers, which is recognised as a general principle of Community law and is laid down in Article 56 of the Financial Regulation and in Article 3(2) of Directive 92/50. It claims that the requirement for an unpaid running-in period imposes a financial burden on all potential tenderers, with the exception of the existing contractor, which enjoys an equivalent advantage since it alone does not need to include in its financial offer the cost of three months’ unpaid running-in activities.

53 The applicant submits that the fact that the existing contractor is a member of a ‘consortium’ with the successful tenderer, which was selected for the contested contract as a result of its lower financial offer, enabled the latter to enjoy a financial advantage which is contrary to the principle of the equal treatment as between tenderers.

54 The applicant is of the opinion that its tender would have obtained a higher ranking if its price/quality ratio had been calculated by disregarding the costs relating to the running-in phase. In that regard, the applicant submits that the costs of the running-in phase must be deducted from the cost of its tender.

55 Lastly, the applicant challenges the fifth paragraph of point 1.3 of Volume A of the tendering specifications. It is of the view that that provision makes it possible for the existing contractor to refuse to allow the new contractor to take over the services before the end of the three-month running-in period.

56 The defendant points out, first of all, that the successful tenderer and the existing contractor are not one and the same. The successful tenderer was simply to subcontract to the existing contractor and is, therefore, a new contractor for the contested contract.

57 The defendant considers, next, that the requirement for an unpaid running-in phase does not, of itself, constitute an infringement of the principle of equal treatment as between tenderers. It is obvious that, in order to take over such an important contract as the contract at issue, the new contractor could not be expected to be fully operational from the very first day. Since the running-in phase would, for each new contractor, be an acclimatisation phase, there would be no payment for that phase.

58 Consequently, the defendant rejects the argument that the successful tenderer benefited unduly from certain financial advantages.

59 With regard to the applicant’s claim that the take-over of the services during the running-in phase was dependent on the goodwill of the existing contractor, the defendant submits that the earlier contract concluded with the existing contractor imposed an obligation to prepare in a timely fashion for the takeover of the services by the new contractor. Furthermore, the existing contractor was obliged to cooperate fully with the new contractor.

b) Findings of the Court

(i) Preliminary remarks

60 As has been recognised by established case-law, in accordance with the principle of equal treatment, comparable situations must not be treated differently and different situations must not be treated in the same way (Joined Cases 117/76 and 16/77 Ruckdeschel and Others [1977] ECR 1753, paragraph 7, and Case 106/83 Sermide [1984] ECR 4209, paragraph 28).

61 In the field of public procurement, the principle of equal treatment as between tenderers assumes a very particular importance. Indeed, it is apparent from the well-established case-law of the Court of Justice that the contracting authority is required to comply with the principle that tenderers should be treated equally (Joined Cases C-285/99 and C‑286/99 Lombardini and Mantovani [2001] ECR I-9233, paragraph 37, and Case C‑315/01 GAT [2003] ECR I‑6351, paragraph 73).

62 It is necessary to consider the first part of the second plea in the light of the principles set out above.

(ii) The alleged infringement of the principle of equal treatment as between tenderers

(1) General observations

63 It is to be recalled, first of all, that the applicant complains that the Commission failed to adhere to the principle of equal treatment by reason of the requirement in the tendering specifications for an unpaid running-in phase.

64 In the light of the case-law (see Case T-160/03 AFConManagement Consultants and Others v Commission [2005] ECR II‑981, paragraph 75 and the case-law cited), according to the applicant, the Commission undermined the equality of opportunity that should be enjoyed by all tenderers.

(2) Whether the requirement for an unpaid running-in phase is discriminatory

General observations

65 The applicant maintains that the Commission failed to adhere to the principle of equal treatment as between tenderers, as laid down in Article 3(2) of Directive 92/50 and in Article 126 of the Implementing Rules.

66 It must be noted in that regard that, according to point 1.7 of Volume A of the tendering specifications, the requirement for an unpaid running-in phase is applicable without distinction to all tenders.

67 The question therefore arises as to whether the requirement in the tendering specifications for an unpaid running-in phase is, by its nature, discriminatory.

Whether the requirement for an unpaid running-in phase entails an inherent advantage for the existing contractor and a tenderer connected to that party by virtue of a subcontract

68 The requirement for a running-in phase enabling the new contractor to become familiar with the earlier version of the technology which it is required to replace seeks to ensure that the quality of the services to be provided is maintained at a high level during that phase. It must be noted that this is a phase during which, on the one hand, the provision of the services in question is still remunerated on the basis of the contract concluded with the existing contractor and, on the other hand, the new contractor is not yet in a position fully to guarantee the quality of services required for the application of the new version of the technology. Thus, the provision for a running-in phase is in the interest of the new contractor itself, since it enables that party in a timely fashion to become fully acquainted with technology with which it will be required to work at a time when it can provide only limited services. In view of the foregoing considerations, the fact that such a phase is unpaid is not, therefore, as such, discriminatory.

69 Nevertheless, according to the applicant, in the present case it is the specific situation in which the existing contractor is placed after the publication of the tendering specifications providing for an unpaid running-in phase, namely that it is envisaged that that party will be the subcontractor of one of the tenderers for the contested contract, which makes such a requirement discriminatory.

70 In that regard, it should be pointed out that the fact that an advantage may be conferred upon an existing contractor by a running-in phase is not the consequence of any conduct on the part of the contracting authority. Unless such a contractor were automatically excluded from any new call for tenders or, indeed, were forbidden from having part of the contract subcontracted to it, it is inevitable that an advantage will be conferred upon the existing contractor or the tenderer connected to that party by virtue of a subcontract, since it is inherent in any situation in which a contracting authority decides to initiate a tendering procedure for the award of a contract which has been performed, up to that point, by a single contractor. That fact constitutes, in effect, an ‘inherent de facto advantage’.

71 The Court of Justice recently held that Directive 92/50 and the other directives concerning the award of public contracts precluded a national rule whereby a tenderer which has been instructed to carry out research, experiments, studies or development in connection with public works, supplies or services is not permitted to apply to submit a tender for those works, supplies or services and where that tenderer is not given the opportunity to prove that, in the circumstances of the case, the experience which it has thus acquired was not capable of distorting competition (Joined Cases C‑21/03 and C‑34/03 Fabricom [2005] ECR I‑1559, paragraph 36).

72 If, according to that judgment, even the exceptional knowledge acquired by a tenderer as a result of work directly connected with the preparation of the tendering procedure in question by the contracting authority itself could not therefore lead to it automatically being excluded from that procedure, there must therefore be even less ground for excluding that tenderer from participating where such exceptional knowledge derives solely from the fact that it participated in the preparation of the call for tenders in collaboration with the contracting authority.

Whether the advantage inherent in the requirement for an unpaid running-in phase should be neutralised

73 It also follows from the case-law cited at paragraph 71 above that the principle that tenderers should be treated equally does not place any obligation upon the contracting authority to neutralise absolutely all the advantages enjoyed by a tenderer where the existing contractor is a subcontractor of that party.

74 To accept that it is necessary to neutralise in all respects the advantages enjoyed by an existing contractor or a tenderer connected to that party by virtue of a subcontract would, moreover, have consequences that are contrary to the interests of the service of the contracting institution in that such neutralisation would entail additional cost and effort for that institution.

75 Nevertheless, in order to comply with the principle of equal treatment in this particular situation, a balance must be struck between the interests involved.

76 Thus, in order to protect as far as possible the principle of equal treatment as between tenderers and to avoid consequences that are contrary to the interests of the service of the contracting institution, the potential advantages of the existing contractor or a tenderer connected to that party by virtue of a subcontract must none the less be neutralised, but only to the extent that it is technically easy to effect such neutralisation, where it is economically acceptable and where it does not infringe the rights of the existing contractor or the said tenderer.

77 With regard to the balancing of the interests concerned from an economic point of view, it must be recalled that the principle of equal treatment as between tenderers derives from the provisions in Section 1 (Articles 56 to 64 bis) of Title IV of the Financial Regulation. Article 2 of the Financial Regulation, which is one of the articles laying down the general principles in that regulation, states that ‘[t]he budget appropriations shall be used in accordance with the principles of economy and sound financial management’. Moreover, according to Article 248(2) EC, sound financial management constitutes a general rule of Community organisation laid down by the Treaty and the Court of Auditors of the European Communities ensures that that rule is complied with.

78 As is apparent from paragraph 68 above, in the present case, not only is the provision of the services in question during the running-in phase remunerated on the basis of the contract concluded with the existing contractor but also the new contractor is not yet at that stage in a position fully to guarantee the quality of the services required for the application of the new version of CORDIS. Moreover, the running-in phase not only ensures the optimum attainment of the quality objectives set out in the call for tenders but also affords the new contractor itself the opportunity for a period of acclimatisation.

79 Accordingly, given, first, that the rights of the existing contractor are not infringed and, secondly, that double payment for the running-in phase would be contrary to one of the principle objectives of the law governing the award of public contracts, which seeks, inter alia, to facilitate the acquisition of the service required in the most economic manner possible, it would be unreasonable, for the purposes of the performance of the contract in question, to waive the requirement for an unpaid running-in phase on the sole ground that one of the prospective tenderers may possibly be connected to the existing contractor by virtue of a subcontract.

80 It must therefore be concluded that, in the present case, the fact that a tenderer connected to the existing contractor by virtue of a subcontract may enjoy an advantage does not require the contracting authority to waive the requirement for an unpaid running-in phase in the tendering specifications in order to avoid an infringement of the principle of equal treatment as between tenderers.

(3) Whether it is possible to refuse to allow the new contractor to take over the services before the end of the three-month running-in period

81 As regards the claim that it is possible to refuse to allow the new contractor to take over the services before the expiry of the three-month running-in period, it must be noted that, according to point 1.3 of Volume A of the tendering specifications, ‘[i]t is not excluded, subject to the approval of the CPO and subject to the agreement of the existing contractor, that parts or all of the service are already taken over during the running-in phase’. Moreover, according to point 1.7 of Volume A of the tendering specifications, ‘in [the] case that parts or all of the service are taken over by the new Contractor during the running-in phase (see 1.3), the new Contractor will be paid as of the date of successful takeover for the parts of the service taken over’.

82 The words ‘subject to … the agreement of the existing contractor’ must be understood in the light of all the conditions governing the takeover of the CORDIS support services and, in particular, those in the earlier contract concluded between the Commission and the existing contractor.

83 With regard to the take over of the CORDIS support services by the new contractor, it follows from point 3.2.1.2 of Annex II to the earlier contract, as amended by the second addendum, that the existing contractor was under an obligation to prepare for and contribute to a complete, timely and smooth takeover by the next contractors and to cooperate fully with the next contractors in order to achieve continuing high standards of quality for CORDIS support services during the takeover phase.

84 Therefore, short of contravening its contractual obligations, the existing contractor was, if necessary, under an obligation to comply with the requirements of any shortening of the three-month running-in phase, pursuant to its obligation of active cooperation.

85 Lastly, the applicant has failed to demonstrate how, from an economic standpoint, the existing contractor had any interest in hindering an early takeover of the CORDIS support services by a new contractor, given that the existing contractor did not, in any event, lose the right to be remunerated up to the end of its own contract.

86 It must therefore be concluded from the foregoing that the fifth paragraph of point 1.3 of Volume A of the tendering specifications does not permit the existing contractor to refuse to allow the new contractor to take over the CORDIS support services before the expiry of the three-month running-in period.

87 The argument put forward by the applicant in this regard must therefore be rejected.

88 In the light of the foregoing, the first part of the second plea in law must be rejected.

2. The second part of the second plea, relating to the failure to make available to all prospective tenderers various relevant technical information from the beginning of the tendering procedure

89 The applicant complains that the Commission failed to make available to all prospective tenderers two categories of relevant technical information, namely, first, information on the acquisition of the Autonomy software by the Commission and, second, information on the technical specifications and the source code for CORDIS.

a) Arguments of the parties

(i) Access to information on the acquisition of the Autonomy software

90 The applicant submits that the Commission failed to communicate in good time information on the acquisition of the Autonomy software to all prospective tenderers.

91 The tendering specifications and background technical documents made available to the prospective tenderers did not make any reference to the fact that, by acquiring the Autonomy software, a solution had in fact already been found to numerous technical problems encountered with CORDIS.

92 The applicant is of the view that the Autonomy software is the ‘corner‑stone’ of CORDIS. It states that it is an intelligent operating system enabling operations to be automated for all forms of information used to conduct communication and business today. The core technology provides a platform for the automatic categorisation, hyper-linking, retrieval and profiling of unstructured information, making possible the automatic delivery of large volumes of personalised information.

93 The applicant explains that Lot 1 was concerned with the gathering and preparation of information and recommendations to the Commission on services for final users. A tender for Lot 1 could, therefore, state that there was a need for additional search software which, when a personal search is made, is able to make a distinction between certain information contained in CORDIS, such as the English word ‘bank’, meaning both ‘bank’ as an institution and ‘river bank’. One of the aims of the contested contract was to find such solutions.

94 The applicant concludes from this that the lack of information on the acquisition of the Autonomy software at the beginning of the tendering procedure obliged it to redesign its whole technical architecture and to review the members of its team, since the introduction of the Autonomy software had an impact on a great number of other features.

95 By contrast, the successful tenderer, supported by its intended subcontractor, which was the existing contractor, was able to devote all its resources to preparing the best possible technical offer, using its privileged information.

96 The applicant disputes the Commission’s contentions that it was open to the use of a better taxonomy system than that offered by the Autonomy software. According to the applicant, such an approach is contradictory in that it could lead to a situation in which the successful tenderer for Lot 1 based its proposal on the use of the Autonomy software and the successful tenderer for the contested contract proposed a solution based on a different taxonomy tool. Moreover, it is unlikely that the Commission, having spent a few hundred thousand euros on the Autonomy software, would take the risk that, at the conclusion of the tendering procedure in question, a tool other than that software would be chosen.

97 In the main, the defendant agrees with the applicant’s descriptions of the functionality of the Autonomy software and the purpose of Lot 1 and the contested contract.

98 However, the defendant disputes the claim that its acquisition of the Autonomy software obliged the tenderers to review the architecture of the CORDIS system, given that that systematic classification tool does not form part of that architecture.

99 The defendant considers that the acquisition of the Autonomy software did not necessitate any change in the tendering specifications. It states that it remained open to any proposal for the acquisition of a taxonomy system that was better than that offered by the Autonomy software and to any other new ideas. Referring, in particular, to point 6.2.3.3 of Volume B of the tendering specifications, headed ‘Indexing, Specific Views and Taxonomies’, the Commission explains that the tenderers for the contested contract were obliged only to propose solutions which would enable complex searches to be carried out in CORDIS. Since the Autonomy software was on the market, the applicant could have included in its bid a proposal that that software or any other tool of that kind should be used. Thus, the second-placed tenderer submitted a very high‑quality bid by proposing another system, which was ‘innovative’ as regards indexing and taxonomy.

100 At the hearing, in response to a question from the Court, the defendant stated that it had published, on a website specifically dedicated to the call for tenders at issue, information on the Autonomy software in response to a request from tenderers and did so with the sole aim of ensuring transparency.

(ii) Access to documentation on the technical architecture and source code for CORDIS

101 The applicant considers that the Commission failed to adhere to the principle that tenderers should be treated equally in that the successful tenderer enjoyed exclusive access to certain technical information and was thus able to submit a much more competitive bid than that of all the other tenderers, obliging the latter to submit higher financial offers.

102 The applicant states that the existing contractor had exclusive access to technical information as to the actual status of the project and, in particular, the CORDIS source code. The applicant submits that no relevant up to date technical information was communicated to the other tenderers, notwithstanding the fact that such information was available. The only useful information communicated to the prospective tenderers was a document describing the technical design specifications for the application which was in place and actually used by the Commission at the time of the call for tenders in question, as well as the detailed and well‑documented source code for the application.

103 With regard to CD 1 and CD 2 and the asset list provided to the potential tenderers, the applicant submits that that technical information related only to the earlier version of CORDIS. That information covered only the period from May 2002 and consisted essentially of bulk statistical data and extremely limited and poor quality technical information, which was therefore outdated, obsolete or of limited value. Lastly, at the hearing, the applicant referred to the fact that, on CD 2, the pages containing the two diagrams of the design for the CORDIS architecture, namely ‘Three-tier architecture’ and ‘Internet Application Server Architecture’, were inadequate.

104 As regards the asset list, the applicant states that a majority of software programmes are machine-specific. A tenderer for the contested contract must therefore describe the applications proposed in a language and with a source code that is specific to those machines. It does not consider the asset list to be clear. Indeed, on the basis of the asset list, it was not possible to determine where the specific programmes for the machines available were to be found. In particular, it was not possible to determine which applications were hosted in which machines, nor the manner in which they were hosted.

105 As regards the importance of the source code for tenders for the contested contract, the applicant explains that a well‑documented source code is the ‘corner-stone’ of any project relating to information technology. In the present case, if the source code is not known, CORDIS is a ‘black box’. The applicant states that a tenderer must envisage a number of options, without ever being able to exhaust all of them, in order to attempt properly to address all possible situations which it may face in the implementation phase. Moreover, it considers that if, in spite of all of this, it is successful, it must bear a significant cost in analysing thousands of lines of unknown source codes and in producing the missing analysis and documentation.

106 The applicant adds that it is necessary to know the source code in order to calculate the tender price. The calculation of bids for contracts in the field of new technology, where an existing application is being taken over, is greatly facilitated by the use of specialist cost-calculating software, such as the software known as ‘Cocomo2’ (COnstructive-COst-MOdel). The number of source code lines constitutes the basic input for use of the Cocomo2 software. In fact, in order to use Cocomo2 software, the first information to be input is the estimated number of lines of source code.

107 With regard to the defendant’s argument that its intention was to foster creativity, the applicant states that, in order to be able to design future projects, it was essential to have very precise and detailed knowledge of the earlier version of CORDIS. It submits that, even if a tenderer were very creative, it would fail if it had to prepare its bid on the basis of incorrect assumptions and incorrect guidelines.

108 The defendant maintains that the successful tenderer did not have privileged access to relevant information. That is demonstrated by the fact that the successful tenderer estimated more staff days than the applicant.

109 The defendant states that, during the tendering procedure, it made every effort to provide comprehensive information on the version of CORDIS in use. It points out that tasks were set in Volumes A and B of the tendering specifications. Additional information was provided at the Information Day held on 7 January 2003 and on the website specifically dedicated to the call for tenders in question.

110 With regard to the content of CD 1 and CD 2, the defendant states that CD 1 contained the specifications for the CORDIS architecture, in the version in use up to the end of the tendering procedure, as well as a special navigation tool designed to facilitate use of CD 1 by the tenderers. CD 2 contained the technical design specifications for CORDIS, test reports, conceptual diagrams of the CORDIS architecture, details of the applications, test plans and a user’s guide, including a document for each data base. With regard to the two missing conceptual diagrams of the CORDIS architecture, that is, ‘Three-tier Architecture’ and ‘Internet Application Server Architecture’ (see paragraph 103 above), the defendant explains that these were not in fact visible. However, those architectures were described in the text and are standard information technology concepts which are not particular to the CORDIS system. The defendant also points out that it was informed of the fact that the two diagrams were not visible only on 14 March 2003, that is, on the Friday afternoon before the deadline for submitting tenders (19 March 2003). It made the missing diagrams available to the tenderers at midday on Tuesday 18 March 2003.

111 As regards the source code, the defendant expressly acknowledges that it was not made available to the tenderers. It states that the source code was neither necessary nor pertinent for the purposes of bidding and evaluation, nor, in particular, for cost calculations. The source code became relevant only at the point at which the services were to be handed over. That is why point 6.8 of Volume B of the tendering specifications provides that the existing contractor is to hand over to the new contractor all relevant objects, including, inter alia, the source code.

112 At the hearing, in response to questions from the Court, the defendant stated that, in its view, there was no particular reason, such as the protection of intellectual property rights, which could have prevented it from making the source code available to the prospective tenderers.

113 As regards the asset list, the defendant states that tenderers for the contested contract were not supposed to receive the bulk of the hardware and software available for the CORDIS project, since the bulk of such equipment was intended for Lot 3. It explains that, for the purpose of preparing tenders for future support services for CORDIS, taking account of the existing equipment was not necessarily the best solution, since some of the hardware is out of date. It was therefore provided in the tendering specifications that it was at the discretion of the tenderers to make alternative proposals.

114 In response to a question put by the Court at the hearing as to the reason for which the Commission had not made available all the technical information at the beginning of the tendering procedure, the Commission explained that, when the call for tenders was launched, the explanatory documents, in particular the asset list, were not yet ready. It therefore made those technical documents available to prospective tenderers only gradually as the preparatory work progressed. The defendant points out that the tendering procedure lasted four months, instead of the usual 36 days, and the prospective tenderers thus had sufficient time to adapt their bids in accordance with the new information. The defendant adds that the tendering specifications clearly state that provision would be made for missing information to be made available on the website specifically dedicated to the call for tenders in question at a later stage.

(iii) The impact on the applicant’s bid of the fact that the applicant was not aware, or was aware only belatedly, of the acquisition of the Autonomy software, as well as the CORDIS technical architecture and source code

(1) The impact of the contested conduct of the Commission on the quality of the applicant’s bid

115 In its argument concerning the alleged manifest errors of the Commission in its assessment of its bid and that of the successful tenderer (the third plea), the applicant disputes a number of allegedly negative comments in the Evaluation Committee’s report on its bid.

116 The applicant submits that it is apparent from a number of negative comments made in the Evaluation Committee’s report (see paragraph 24 above) that the missing technical information to which it was granted belated access had a negative impact on the assessment of the quality of its bid. With regard to the first award criterion, it refers to the first, second, third and sixth comments and, with regard to the second award criterion, to the fourth comment.

117 As regards the first award criterion and the first comment, the applicant considers essentially that, while some technical elements were succinctly described, that is simply because the accessible technical information was insufficiently detailed in that area. As regards the second comment, the applicant states that, since it did not have access to the information which was available to the existing contractor, it was obliged to ‘develop lengthy scenarios’ to cover all theoretically possible structures and practices. With regard to the third comment, it maintains that, while its bid was considered to be too descriptive as regards search and functionality assumptions, that is because the prospective tenderers had been made aware of the fundamental role of the Autonomy software in the CORDIS technical platform only at a very late stage. As regards the sixth comment, the applicant considers that, while its bid was considered to contain too much unnecessary detail and redundant material and to be lacking in concrete proposals, that is because its bid was based on the need to maintain in operation an existing information system, for which all the tenderers, with the exception of the existing contractor, did not have the full picture.

118 As regards the second award criterion and the fourth comment, the applicant submits that more CORDIS-specific discussion was not possible as that would have required more information on how CORDIS operated at that time. Only a tenderer with access to recent internal information could therefore have taken the risk of making firm statements in that regard.

119 The defendant disputes the assertion that the successful tenderer obtained higher marks as a result of its privileged access to information and material. In that regard, the defendant puts forward a number of examples to illustrate the weakness of the applicant’s arguments.

120 With regard to the first award criterion, the Commission explains, in particular, that when the successful tenderer’s bid was evaluated, it was criticised as being a technical proposal based on the existing system and lacking a fresh approach.

121 With regard to the second award criterion (fourth comment), the defendant refers, in particular, to point 6.2.1 of Volume B of the tendering specifications for the contested contract, according to which the tenderers were required only to describe the basic requirements of what is needed for the continuation and evolution of CORDIS and which stated that, as far as ‘how’ was concerned, the minimal requirements were set out in the tendering specifications.

(2) The impact of the contested conduct of the Commission on the price of the applicant’s bid

122 In response to a written question by the Court, the applicant stated that, as information was missing or sent belatedly by the Commission during the tendering procedure, its bid was subject to a risk factor in the range of 25 to 30%. The risk factor as regards that information was broken down as follows:

– data base: 7%

– Autonomy software: 7%

– source code: 5%

– technical design specifications (logical design of the software) and documentation: 11%.

123 At the hearing, the applicant explained that it did those calculations using Cocomo2 software. In response to a question put by the Court, it clarified the purpose of the Cocomo2 software and how it functions.

124 Thus, Cocomo2 is based on a mathematical formula which takes as input the lines of source code and makes it possible to calculate the effort required to do any work based on them. The corresponding equation contains 22 parameters that represent equivalent real‑life factors which influence the effort required to write a programme or implement any task related to a software application. The 5 parameters representing multiple‑cost drivers are called ‘Effort Multipliers’ (EM) and the 17 parameters of additional costs are called ‘Scale Factors’ (SF).

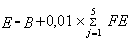

125 Moreover, for each parameter, that model provides six possible ratings as well as detailed instructions for choosing the appropriate rating. The following ratings can thus be attributed to each parameter, depending on the case: ‘Very Low’, ‘Low’, ‘Nominal’, ‘High’, ‘Very High’ and ‘Extra High’. For each of those ratings, there is a corresponding value expressed in points. The number of points decreases in proportion to the rating given – i.e. the higher the rating attributed to the parameter, the lower the number of points will be.

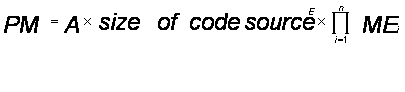

126 The estimated effort for a project with a source code of a given size is expressed in person/months (PM) and is evaluated according to the following formula (A and B being constants):

where

127 According to the applicant, in the case of the call for tenders at issue, it can be assumed that the 22 parameters will be evaluated in the same manner for each of the tenderers, regardless of their prior knowledge of CORDIS and the material available in the call for tenders at issue, with the exception of the two parameters representing, first, knowledge of the design of the application that is to be developed and, second, the environment used by the application, namely the ‘PREC parameter’, relating to the degree of familiarity, and the ‘AEXP parameter’, relating to experience of the application. The ‘PREC parameter’ is one of the 17 SF. The ‘AEXP parameter’ is one of the 5 EM.

128 According to the applicant, the formula set out at paragraph 126 above can be applied twice in order to calculate the impact in the two following cases:

– in the case of a tenderer who is very familiar with the earlier version of CORDIS, assuming that the rating ‘Very High’ will therefore be attributed for both the PREC and the AEXP parameters;

– in the case of a tenderer who has a very limited knowledge of the earlier version of CORDIS, assuming that the rating ‘Very Low’ will therefore be attributed for both the PREC and the AEXP parameters.

129 According to the applicant, by taking, for the purpose of that calculation, a source code estimated at 5 000 lines, the result will be an estimated effort of 15.4 PM for the bid of the tenderer in the first situation and an estimated effort of 25.9 PM for the bid of the tenderer in the second situation. That means that the estimated effort for the applicant would be approximately 40% higher than that in the case of a tenderer who is very familiar with all the technical information and the source code for the earlier version of CORDIS. The applicant also submits that, even if, for the purpose of the comparison, parameters corresponding to the ratings ‘High’ and ‘Low’, or indeed ‘High’ and ‘Very Low’, were to be substituted, there would still be a difference of 30%.

130 The defendant considers, first, that the calculations made using Cocomo2 software should be undertaken by an independent expert appointed for that purpose.

131 The defendant states that the applicant’s decision as to the ratings to be attributed to the PREC and AEPX parameters was subjective. The defendant points out that, in the tender documentation, the applicant presented itself as an organisation with great experience in the field of information technology and communication, whereas now, in putting forward the risk factor created by the alleged lack of technical information, it presents itself as a tenderer with below average knowledge in that field.

132 The defendant doubts whether the basis on which the applicant gives itself a ‘Very Low’ rating score for the PREC and AEXP parameters is justified. It states that, for the purpose of the calculation using the Cocomo2 software, the applicant should have used the ‘Nominal’ rating for those parameters.

133 The defendant also disputes the ‘Very High’ rating score given by the applicant to the successful tenderer. In so doing, the applicant disregards the fact that the successful tenderer is not totally familiar with the CORDIS system either, even allowing for the fact that part of the contested contract was to be subcontracted to the existing contractor.

134 With regard, first, to the PREC parameter, the defendant explains that it deals with the following matters: the understanding of the undertaking in question of product objectives, experience of working with related software systems, the concurrent development of associated new hardware and operational procedures and the need for innovative data processing architecture (algorithms). The defendant doubts whether the applicant can properly categorise itself as ‘Very Low’ in respect of all those matters. That would mean that it has a ‘general’ understanding of the product objectives, ‘moderate experience’ and ‘extensive need’ for concurrent development and ‘considerable need’ for innovative data processing algorithms.

135 With regard, secondly, to the AEXP parameter, the defendant explains that the applicant once again gives itself a ‘Very Low’ score rating, which indicates less than two months’ experience of the application concerned. The applicant thus claims that it is not at all familiar with the kind of project with which the call for tenders at issue is concerned and that its team has very limited experience of that kind of application.

136 The defendant is of the view, secondly, that the applicant has failed to explain the breakdown of the 30% risk factor into a number of elements relating, respectively, to the data bases (7%), the Autonomy software (7%), the source code (5%) and the technical design specifications (11%).

137 The Commission considers that the 11% increase in respect of person/day costs attributed to the alleged failure to communicate the technical specifications must be discounted, since those technical specifications were indeed made available to the applicant. Moreover, the fact that the two diagrams of the CORDIS architecture were not visible on CD 2 does not amount to a risk factor of 11%.

138 The defendant also disputes the 7% increase in costs attributed to the fact, as alleged, that it became aware only belatedly of the acquisition of the Autonomy software, given that that software is well known on the market.

139 Finally, the defendant questions whether the source code warrants only a 5% risk factor, when, in its view, the applicant’s whole contention was that the failure to provide the technical design specifications (to which it gives an 11% rating) and the source code was a very serious matter.

b) Findings of the Court

(i) Preliminary remarks

140 By maintaining that the Commission granted access to certain essential information only to the successful tenderer, the applicant claims that the Commission failed to adhere to the principle that there should be no discrimination as between tenderers.

141 First of all, it is to be borne in mind that the principle of equal treatment is of particular importance in the field of public procurement (see paragraphs 60 to 61 above). In the context of such a procedure, the Commission is required to ensure, at each stage of the procedure, equal treatment and, thereby, equality of opportunity for all the tenderers (see AFCon Management Consultants and Others v Commission, paragraph 75 and the case-law cited).

142 The case-law demonstrates that the principle of equal treatment implies in particular an obligation of transparency so that it is possible to verify that that principle has been complied with (Case C-92/00 HI [2002] ECR I‑5553, paragraph 45, and Case C‑470/99 Universale-Bau and Others [2002] ECR I‑11617, paragraph 91).

143 Under the principle of equal treatment as between tenderers, the aim of which is to promote the development of healthy and effective competition between undertakings taking part in a public procurement procedure, all tenderers must be afforded equality of opportunity when formulating their tenders, which therefore implies that the tenders of all competitors must be subject to the same conditions (see, to that effect, Case C‑19/00 SIAC Construction [2001] ECR I‑7725, paragraph 34, and Universale-Bau and Others, paragraph 93).

144 The principle of transparency, which is its corollary, is essentially intended to preclude any risk of favouritism or arbitrariness on the part of the contracting authority. It implies that all the conditions and detailed rules of the award procedure must be drawn up in a clear, precise and unequivocal manner in the notice or tendering specifications (Case C‑496/99 P Commission v CAS Succhi di Frutta [2004] ECR I‑3801, paragraphs 109 to 111).

145 The principle of transparency therefore also implies that all technical information relevant for the purpose of a sound understanding of the contract notice or the tendering specifications must be made available as soon as possible to all the undertakings taking part in a public procurement procedure in order, first, to enable all reasonably well-informed and normally diligent tenderers to understand their precise scope and to interpret them in the same manner and, secondly, to enable the contracting authority actually to verify whether the tenderers’ bids meet the criteria of the contract in question.

(ii) The alleged unequal treatment by comparison with the successful tenderer as regards access to certain technical information

(1) General observations

146 First of all, the applicant complains that the Commission failed to adhere to the principle of equal treatment because of an alleged delay in making certain technical information available to the tenderers, with the exception of the successful tenderer. In the light of the case-law cited at paragraphs 60 and 61 and at paragraphs 141 to 144 above, the Commission undermined the equality of opportunity of all the tenderers as well as the principle of transparency, which is the corollary of the principle of equal treatment.

147 Next, even on the assumption that it were correct, such an undermining of equality of opportunity and the principle of transparency would constitute a defect in the pre-litigation procedure adversely affecting the right of the parties concerned to information. According to settled case-law, a procedural defect can lead to the annulment of the decision in question only if it is shown that, but for that defect, the administrative procedure could have had a different outcome if the applicant had had access to the information in question from the beginning of that procedure and if there was even a small chance that the applicant could have brought about a different outcome to the administrative procedure (see Case C‑194/99 P Thyssen Stahl v Commission [2003] ECR I‑10821, paragraph 31 and the case‑law cited, and Joined Cases T‑191/98 and T‑212/98 to T‑214/98 Atlantic Container Line and Others v Commission [2003] ECR II‑3275, paragraphs 340 and 430).

148 In that connection, the Court will examine, first of all, whether the unequal treatment alleged, consisting in a delay in providing the tenderers other than the successful tenderer with certain technical information, constitutes, as such, a procedural defect in that information that was in fact necessary for the preparation of the tenders was not made available to all the tenderers as soon as possible.

149 If such a defect is established, the Court will then examine whether, but for that defect, the procedure could have had a different outcome. From that point of view, such a defect can constitute an infringement of the equality of opportunity of tenderers only in so far as the explanations provided by the applicant demonstrate, in a plausible and sufficiently detailed manner, that the procedure could have had a different outcome as far as it was concerned.

(2) The late provision by the Commission of certain technical information

150 The Court notes, first of all, that the successful tenderer was fully aware of all the technical specifications for the CORDIS data bases as well as for the Autonomy software before the opening of the tendering procedure, given that its subcontractor, which, according to the tender submitted, was to carry out at least 35% of the proposed tasks, was the existing contractor at the time when the tendering procedure was opened.

151 Moreover, it is not disputed that the Commission had at its disposal technical specifications for the CORDIS data bases before the opening of the tendering procedure, namely at the end of November 2002.

152 Nor does the defendant dispute the fact that it made the technical specifications for the CORDIS data bases available to all the prospective tenderers only gradually during the tendering procedure.

153 In fact, the Commission only made available part of the technical specifications for the CORIDS data bases one month after the tendering procedure had opened, on 20 December 2002, on CD 2, and only published further technical information, in the asset list, on 5 February 2003, that is, only six weeks before the deadline for submitting tenders expired.

154 The justification put forward by the defendant, namely that it had not yet prepared all the information at the beginning of the tendering procedure, must be rejected since, in order to ensure that all prospective tenderers enjoyed equality of opportunity, it could have waited until it was in a position to make all the information in question available to all prospective tenderers in order to launch that tendering procedure.

155 The Court finds, next, that, given that its intended subcontractor for the performance of part of the contested contract was the incumbent contractor at the time of the opening of the tendering procedure, the successful tenderer was in a position, from the beginning of the tendering procedure, to have full knowledge of how the Autonomy software operated, since a trial version had been installed in the version of CORDIS in operation at that time. Moreover, the intended subcontractor of the successful tenderer was also involved in the preparation for the acquisition of the Autonomy software by the Commission, which took place during the tendering procedure. It is thus highly likely that the successful tenderer was fully aware of that acquisition from the outset.

156 The defendant does not dispute that the other tenderers were informed of that acquisition only via the publication of the document entitled ‘Superquest – Implementation of Release 6 and beyond’ on 18 February 2002, that is, only a month before the deadline for submitting tenders expired.

157 Therefore, the Court finds that the Commission made available to all the prospective tenderers information on the technical specifications for the CORDIS data bases and information on the acquisition of the Autonomy software only gradually during the tendering procedure, whereas the successful tenderer had that information from the beginning of that procedure, since it was provided that it would subcontract part of the contested contract to the existing contractor.

(3) Whether it is necessary to neutralise the advantages enjoyed by the successful tenderer

158 What is to be borne in mind in this regard are the considerations relating to the examination as to whether it is discriminatory to lay down a requirement for an unpaid running-in phase in the tendering specifications (see paragraphs 68 to 80 above), in which it was stated that the principle of equal treatment as between tenderers requires that the potential advantages that may be enjoyed by the existing contractor or the tenderer connected to that party by virtue of a subcontract must be neutralised only to the extent that it is not necessary for such advantages to be maintained, that is to say, where it is easy to effect such neutralisation, where it is economically acceptable and where it does not infringe the rights of the existing contractor or the said tenderer.

159 In the present case, the Commission had full information on the technical specifications for the CORDIS data bases at its disposal from the beginning of the tendering procedure in question. It could therefore easily have made it available to all the tenderers in the form of an annex to the tendering specifications. Moreover, it is clear that it could also have easily informed all the prospective tenderers, without incurring additional costs, of the acquisition of the Autonomy software immediately after it had taken place, namely at the end of December 2002. Lastly, it must be noted that the defendant expressly acknowledges that there was no particular reason, such as the protection of intellectual property rights, which could have prevented it from making the source code available to third parties.

160 It follows from the foregoing that, in the present case, in accordance with the principle of equal treatment as between tenderers, the advantages enjoyed by the existing contractor or by the successful tenderer must be neutralised. Consequently, it is apparent that the unequal treatment consisting in a delay in making certain technical information available to the tenderers, with the exception of the successful tenderer, constitutes a procedural defect.

161 It is therefore necessary to examine whether, but for that defect, the tendering procedure in question could have had a different outcome.

(iii) The relevance to the bids for the contested contract of the information belatedly made available by the Commission

162 If it were established that the information belatedly provided to the tenderers other than the successful tenderer was irrelevant for the purpose of preparing bids for the contested contract, a delay in communicating that information would not, in any event, represent an advantage for the successful tenderer and would not therefore constitute a procedural defect amounting to an infringement of the principle of equal treatment as between tenderers, as the applicant claims.

(1) The relevance of the information on the acquisition of the Autonomy software

163 With regard to the relevance of the information on the acquisition of the Autonomy software, the Court notes, first of all, that it is apparent from the parties’ common descriptions that that software is a complex classification tool enabling final users to carry out searches in a number of contexts and, in particular, in a number of languages.

164 Secondly, it is clear from the description of the contested contract at point 4 of Volume A of the tendering specifications that tenderers for that contract were required in their bids to submit proposals which could ensure the development of the technical infrastructure used by the contractors for the other lots and the Commission, such as, for example, ‘the Web Content Management System’, and that the successful tenderer for the contested contract was also required to ‘develop new tools and features, some of which [are] for experimental purposes’.

165 Thirdly, account must be taken of the fact that, according to point 6.2.3.3 of Volume B of the tendering specifications, headed ‘Indexing, Specific Views and Taxonomies’, there exists for the tenderers for the contested contract ‘the possibility to make use of available products to implement, for example, “taxonomy building”, but these should have long-term application and be consistent with the CORDIS architecture’.

166 It is apparent from the description of the tasks to be carried out by a tenderer for the contested contract and from point 6.2.3.3 of Volume B of the tendering specifications that the tenderers for the contested contract were free to propose any complex taxonomy software available on the market, including the Autonomy software.

167 It follows that the simple fact that the Commission purchased the Autonomy software during the tendering procedure did not lead it to evaluate a bid proposing a different complex research tool less favourably.

168 For the sake of completeness, that finding is also supported by the fact that the evaluation report states, with regard to the first award criterion, that the bid submitted by the second-placed tenderer for the contested contract was considered by the Evaluation Committee to be of very high quality, that tenderer having proposed another system, which was ‘innovative’ as regards indexing and taxonomy, which demonstrates that, in that regard, the Commission adhered to the relevant conditions laid down in the tendering specifications.

169 It follows that, throughout the tendering procedure, the knowledge that the Commission had acquired the Autonomy software could not have had any significance for the purpose of evaluating the bids.

170 In the light of the foregoing, the Court considers, with regard to the information on the acquisition of the Autonomy software, that the applicant has failed to demonstrate sufficiently how knowledge of the acquisition of the Autonomy software by the Commission could have constituted an advantage of any kind for the successful tenderer in bidding for the contested contract.

(2) The relevance of the information contained in the documentation on the CORDIS technical architecture and source code

171 First, as regards the allegedly incomplete documentation on the CORDIS technical architecture, the Court notes that the defendant does not dispute that the general purpose of the technical information on CD 1 and CD 2 was to supplement that already included in the tendering specifications.

172 Secondly, with regard to the asset list, the Court considers that the applicant explained convincingly, and in such a manner that the Commission has not been able to counter its assertions, that knowledge of the materials and software used at that time could have assisted in the preparation of the applications to be provided by a tenderer for the contested contract, since such a tenderer had to ensure, first, the interoperability of the new hardware and existing hardware and, second, that the new applications functioned with the existing hardware.