JUDGMENT OF THE GENERAL COURT (Third Chamber)

9 April 2014 (*)

(Community trade mark — Opposition proceedings — Application for the Community figurative mark DORATO — Earlier Community and national figurative trade marks representing bottle neck labels — Relative ground for refusal — Likelihood of confusion — Article 8(1)(b) of Regulation (EC) No 207/2009 — Rule 50(1) of Regulation (EC) No 2868/95)

In Case T‑249/13,

MHCS, established in Épernay (France), represented by P. Boutron, N. Moya Fernández and L.-É. Balleydier, lawyers,

applicant,

v

Office for Harmonisation in the Internal Market (Trade Marks and Designs) (OHIM), represented by P. Bullock, N. Bambara and A. Folliard-Monguiral, acting as Agents,

defendant,

the other party to the proceedings before the Board of Appeal of OHIM, intervener before the General Court, being

Ambra SA, established in Warsaw (Poland), represented by M. KaczanParchimowicz, lawyer,

ACTION brought against the decision of the Second Board of Appeal of OHIM of 19 February 2013 (Case R 1877/2011-2), relating to opposition proceedings between MHCS and Ambra SA,

THE GENERAL COURT (Third Chamber),

composed of S. Papasavvas (Rapporteur), President, N.J. Forwood and E. Bieliūnas, Judges,

Registrar: J. Weychert, Administrator,

having regard to the application lodged at the Court Registry on 2 May 2013,

having regard to the response of OHIM lodged at the Court Registry on 24 July 2013,

having regard to the response of the intervener lodged at the Court Registry on 29 July 2013,

having regard to the decision of 23 September 2013 not to allow the lodging of a reply,

further to the hearing on 29 January 2014,

gives the following

Judgment

Background to the dispute

1 On 25 May 2010, the intervener, Ambra SA, filed an application for registration of a Community trade mark with the Office for Harmonisation in the Internal Market (Trade Marks and Designs) (OHIM) pursuant to Council Regulation (EC) No 207/2009 of 26 February 2009 on the Community trade mark (OJ 2009 L 78, p. 1).

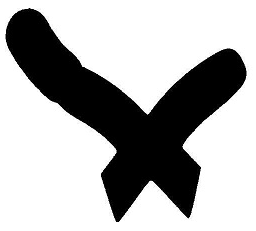

2 Registration as a mark was sought for the following figurative sign:

3 The goods in respect of which registration was sought are in Class 33 of the Nice Agreement concerning the International Classification of Goods and Services for the Purposes of the Registration of Marks of 15 June 1957, as revised and amended, and correspond to the following description: ‘alcoholic beverages (except beers)’.

4 The Community trade mark application was published in Community Trade Marks Bulletin No 2010/113 of 22 June 2010.

5 On 22 September 2010, the applicant, MHCS, filed a notice of opposition pursuant to Article 41 of Regulation No 207/2009 against registration of the mark applied for in respect of the goods referred to in paragraph 3 above.

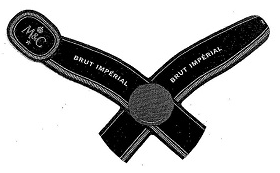

6 The opposition was based on the following earlier figurative marks:

– Community trade mark No 1720796:

– Community trade mark No 3603404:

– French trade mark No 1416039 :

– French trade mark No 63466976 :

7 The goods in respect of which those marks were registered are in, inter alia, Class 33 and correspond, for that class, to the following description: ‘alcoholic beverages (excepting beers)’.

8 The ground relied on in support of the opposition was that set out in Article 8(1)(b) of Regulation No 207/2009.

9 On 25 July 2011, the Opposition Division rejected the opposition.

10 On 13 September 2011, the applicant filed a notice of appeal with OHIM, pursuant to Articles 58 to 64 of Regulation No 207/2009, against the Opposition Division’s decision.

11 By decision of 19 February 2013 (‘the contested decision’), the Second Board of Appeal of OHIM dismissed the appeal. It found, first, that the applicant’s argument aimed at claiming that the earlier marks had acquired enhanced distinctiveness, that the evidence submitted in that regard had been put forward for the first time before the Board of Appeal and that that evidence was therefore inadmissible. Secondly, it found that, given that the signs at issue were visually, phonetically and conceptually dissimilar, one of the conditions for the application of Article 8(1)(b) of Regulation No 207/2009 had not been satisfied, with the result that the opposition had to be rejected, despite the identity of the goods at issue.

Forms of order sought

12 The applicant claims that the Court should:

– annul the contested decision;

– order OHIM and the intervener to pay the costs, including those incurred in the proceedings before OHIM.

13 OHIM contends that the Court should:

– dismiss the action;

– order the applicant to pay the costs.

14 The intervener contends that the Court should:

– dismiss the action;

– order the applicant to pay the costs, including those incurred in the course of the proceedings before OHIM.

Law

15 In support of its action, the applicant relies on two pleas in law alleging, first, infringement of Rule 50(1) of Commission Regulation (EC) No 2868/95 of 13 December 1995 implementing Council Regulation (EC) No 40/94 on the Community trade mark (OJ 1995 L 303, p. 1) and of Article 76(2) of Regulation No 207/2009 and, secondly, infringement of Article 8(1)(b) of Regulation No 207/2009.

The first plea, alleging infringement of Rule 50(1) of Regulation No 2868/95 and Article 76(2) of Regulation No 207/2009

16 The applicant submits, in essence, that, first, by rejecting the evidence aimed at proving that the earlier marks had acquired enhanced distinctiveness and, secondly, by failing to state the reasons why it did not take that evidence into account, the Board of Appeal misinterpreted Article 76(2) of Regulation No 207/2009.

17 By those arguments, which OHIM and the intervener dispute, the applicant puts forward, in essence, two claims relating, first, to the statement of reasons for the contested decision and, secondly, to the rejection of the evidence produced for the first time before the Board of Appeal.

18 As regards, first, the claim relating to the statement of reasons for the contested decision, it must be borne in mind that, under Article 75 of Regulation No 207/2009, decisions of OHIM are required to state the reasons on which they are based. That duty to state reasons has the same scope as that under Article 296 TFEU, pursuant to which the reasoning of the author of the act must be shown clearly and unequivocally. It has two purposes: to allow interested parties to know the justification for the measure taken so as to enable them to protect their rights and to enable the Courts of the European Union to exercise their power to review the legality of the decision (see judgment of 12 July 2012 in Case T‑389/11 Gucci v OHIM — Chang Qing Qing (GUDDY), not published in the ECR, paragraph 16 and the case-law cited).

19 In the present case, it must, first, be pointed out that, in paragraphs 14 to 20 of the contested decision, the Board of Appeal examined the admissibility of the evidence which was submitted for the first time before it and was aimed at proving that the earlier marks had acquired enhanced distinctiveness through use. To that effect, it first of all referred to the circumstances of the case, the provisions in question and the case-law relating to those provisions. It then stated that, during the opposition proceedings, the applicant had not claimed that the earlier marks had acquired enhanced distinctiveness or submitted any evidence in that respect and that that claim had been raised only after the decision of the Opposition Division had been adopted. Furthermore, it stated that the applicant had given no reason why it had not made that claim within the time-limit set and stated that it was not aware of any factors or circumstances which might have prevented it from doing so. It concluded that, in the absence of any legitimate reason for the failure to comply with the time-limit which it had set, the evidence in question was inadmissible. For the sake of completeness, it stated, in paragraph 21 of the contested decision, that the figurative elements contained in the earlier marks were only weakly distinctive, and therefore, even if they were found to have acquired an additional degree of enhanced distinctiveness through use, their total distinctiveness would still not be high.

20 It must therefore be held that the applicant errs in claiming that the Board of Appeal did not state, to the requisite legal standard, the reasons for refusing to take the evidence in question into account since the reasoning which the Board of Appeal followed in that regard is clear from the contested decision.

21 As regards, secondly, the claim relating to the rejection of the evidence submitted for the first time before the Board of Appeal, it must be borne in mind that it is apparent from the third subparagraph of Rule 50(1) of Regulation No 2868/95 that, where the appeal is directed against a decision of an Opposition Division, the Board is to limit its examination of the appeal to facts and evidence presented within the timelimits set or specified by the Opposition Division in accordance with Regulation No 207/2009 and Regulation No 2868/95, unless the Board considers that additional or supplementary facts and evidence should be taken into account pursuant to Article 76(2) of the Regulation No 207/2009.

22 As is clear from the wording of Article 76(2) of Regulation No 207/2009, OHIM may disregard facts or evidence which have not been submitted in due time by the parties concerned.

23 It is apparent from such wording that, as a general rule and unless otherwise specified, the submission of facts and evidence by the parties remains possible after the expiry of the timelimits to which such submission is subject under the provisions of Regulation No 207/2009 and that OHIM is in no way prohibited from taking account of facts and evidence which are submitted late (Case C‑29/05 P OHIM v Kaul [2007] ECR I‑2213, paragraph 42).

24 However, it is equally apparent from that wording that a party has no unconditional right to have facts and evidence submitted out of time taken into consideration by OHIM. In stating that the latter ‘may’, in such a case, decide to disregard facts and evidence, Article 76(2) of Regulation No 207/2009 grants OHIM a broad discretion to decide, while giving reasons for its decision in that regard, whether or not to take such information into account (OHIM v Kaul, paragraph 43).

25 Where OHIM is called upon to give a decision in the context of opposition proceedings, taking such facts or evidence into account is particularly likely to be justified where OHIM considers, first, that the material which has been produced late is, on the face of it, likely to be relevant to the outcome of the opposition brought before it and, second, that the stage of the proceedings at which that late submission takes place and the circumstances surrounding it do not argue against such matters being taken into account (OHIM v Kaul, paragraph 44).

26 If OHIM were compelled to take into consideration, in all circumstances, the facts and evidence submitted by the parties to opposition proceedings outside of the time-limits set to that end under the provisions of Regulation No 207/2009, those provisions would be rendered redundant (OHIM v Kaul, paragraph 45).

27 In the present case, it is common ground that, in the course of the proceedings before the Opposition Division, the applicant did not rely on the fact that the earlier marks had acquired enhanced distinctiveness through use or put forward evidence in that regard.

28 In those circumstances, it was, in principle, open to the Board of Appeal, in accordance with Article 76(2) of Regulation No 207/2009, to disregard that evidence.

29 In the present case, it is apparent from the reasons for the contested decision, which are summarised in paragraph 19 above, that the Board of Appeal actually exercised its discretion under Article 76(2) of Regulation No 207/2009, for the purposes of deciding, in a reasoned manner and having due regard to all the relevant circumstances, whether it was necessary to take into account the additional evidence submitted to it in order to make the decision it was called upon to give, as required by the case-law (see, to that effect, Case C‑610/11 P Centrotherm Systemtechnik v OHIM and centrotherm Clean Solutions [2013] ECR, paragraph 110). Stating that there was no legitimate reason for the failure to comply with the time-limit which had been set for its submission, the Board of Appeal, exercising its broad discretion, found that the evidence in question was inadmissible.

30 Moreover, the applicant has put forward nothing that could suggest that that assessment is manifestly incorrect.

31 It confines itself to stating, in its application, that it legitimately thought that the distinctiveness of its trade marks would not be challenged by the Opposition Division and that it was only in response to an arbitrary and unreasoned statement in the Opposition Division’s decision that it provided evidence on appeal contrary to that statement, with the result that that evidence is admissible.

32 In that regard, it must be borne in mind that, not only does a party have no unconditional right to have facts and evidence submitted out of time taken into consideration by OHIM (see paragraph 24 above), but that, moreover, the applicant has not provided any information to justify the belated submission of the evidence in question. More specifically, it did not state, before the Board of Appeal, that that belated submission was aimed at responding to an alleged arbitrary and unreasoned assertion in the Opposition Division’s decision. Moreover, the Opposition Division simply stated, correctly, as is apparent from the file, that the applicant had not explicitly claimed that the earlier marks had acquired distinctiveness through use and that, consequently, its assessment would be confined to the distinctiveness per se of those marks. In that respect, it must be pointed out that reliance on distinctive character acquired through use is a legal issue which is independent of the issue of the inherent distinctive character of the mark in question. Consequently, where a party does not rely before OHIM on the distinctive character acquired by its mark, OHIM is not required to examine, of its own motion whether that distinctive character exists (see judgment of 10 March 2010 in Case T‑31/09 Baid v OHIM (LE GOMMAGE DES FACADES), not published in the ECR, paragraph 41 and the case-law cited). Lastly, the passage from the Opposition Division’s decision which was referred to by the applicant in its application to lodge a reply and at the hearing does not relate to any alleged distinctive character of the earlier marks as such, which was acquired through use. It relates inter alia to the distinctive character of one of the figurative elements of those marks, in this instance the ‘x’-shaped element, which the Opposition Division found, correctly as is apparent from paragraph 58 below, to be lower than average.

33 It follows from those considerations that there is nothing which makes it possible to call into question the Board of Appeal’s finding that the evidence submitted for the first time before it had to be rejected as inadmissible.

34 In addition, it is apparent from paragraph 21 of the contested decision that the Board of Appeal, in essence, found, in the exercise of its broad discretion, that that evidence was irrelevant to the decision it was called upon to make. It stated, for the sake of completeness, that the figurative elements contained in the earlier marks were only weakly distinctive, and thus, even if they were found to have acquired an additional degree of enhanced distinctiveness through use, their total distinctiveness would still not be high. The irrelevance of the facts and evidence submitted to OHIM by the parties to opposition proceedings, outside the timelimits prescribed for that purpose, is precisely one of the criteria which OHIM may take into account in deciding, in the exercise of the discretion which it enjoys under Article 76(2) of Regulation No 207/2009, that there is no need to take account of those facts and evidence (order of 4 March 2010 in Case C‑193/09 P Kaul v OHIM, not published in the ECR, paragraph 39).

35 It follows from all of the foregoing that the first plea must be rejected.

The second plea, alleging infringement of Article 8(1)(b) of Regulation No 207/2009

36 The applicant submits that, having regard to the fact that the goods at issue are identical, the signs at issue are similar and the earlier marks have distinctive character, both per se and acquired through use, there is a likelihood of confusion within the meaning of Article 8(1)(b) of Regulation No 207/2009.

37 The Board of Appeal found that the signs at issue were dissimilar overall. Moreover, since one of the conditions for the application of Article 8(1)(b) of Regulation No 207/2009 was not satisfied, it found that the opposition had to be rejected, in spite of the identity of the goods in question.

38 Article 8(1)(b) of Regulation No 207/2009 provides that, upon opposition by the proprietor of an earlier trade mark, the trade mark applied for must not be registered if because of its identity with, or similarity to, an earlier trade mark and the identity or similarity of the goods or services covered by the trade marks, there exists a likelihood of confusion on the part of the public in the territory in which the earlier trade mark is protected. The likelihood of confusion includes the likelihood of association with the earlier trade mark. Furthermore, under Article 8(2)(a)(ii) of Regulation No 207/2009, ‘earlier trade marks’ means Community trade marks and trade marks registered in a Member State with a date of application for registration which is earlier than the date of application for registration of the Community trade mark.

39 According to settled case-law, the risk that the public might believe that the goods or services in question come from the same undertaking or from economicallylinked undertakings constitutes a likelihood of confusion. According to the same case-law, the likelihood of confusion must be assessed globally, according to the perception which the relevant public has of the signs and the goods or services in question, account being taken of all factors relevant to the circumstances of the case, including the interdependence between the similarity of the signs and that of the goods or services covered (see Case T‑162/01 Laboratorios RTB v OHIM — Giorgio Beverly Hills (GIORGIO BEVERLY HILLS) [2003] ECR II‑2821, paragraphs 30 to 33 and the case-law cited).

40 For the purposes of applying Article 8(1)(b) of Regulation No 207/2009, a likelihood of confusion presupposes both that the two marks are identical or similar and that the goods or services which they cover are identical or similar. Those conditions are cumulative (see Case T‑316/07 Commercy v OHIM — easyGroup IP Licensing (easyHotel) [2009] ECR II‑43, paragraph 42 and the case-law cited).

41 In the present case, it must be noted, as was correctly stated by the Board of Appeal and is not disputed by the applicant, that the relevant public consists of the general public in the territory in which the earlier marks were registered, namely France and the European Union as a whole.

42 It must also be pointed out that it is common ground between the parties that the goods at issue are, as the Board of Appeal correctly found, identical.

43 The merits of the present plea must be examined on the basis of those considerations.

The comparison of the signs

44 The global assessment of the likelihood of confusion, in relation to the visual, phonetic or conceptual similarity of the signs in question, must be based on the overall impression given by the signs, bearing in mind, in particular, their distinctive and dominant components. The perception of the marks by the average consumer of the goods or services in question plays a decisive role in the global appreciation of such likelihood of confusion. In this regard, the average consumer normally perceives a mark as a whole and does not engage in an analysis of its various details (see Case C‑334/05 P OHIM v Shaker [2007] ECR I‑4529, paragraph 35 and the case-law cited).

45 In the present case, the Board of Appeal, in essence, found, first, that the distinctive character of the figurative elements of the earlier marks was weak, secondly, that the distinctive and dominant element of the mark applied for was the word element ‘dorato’ and, thirdly, that the signs at issue were visually, phonetically and conceptually dissimilar.

46 The applicant submits, in essence, first, that the earlier marks are distinctive per se, secondly, that the Board of Appeal erred in finding that the word element ‘dorato’ was distinctive and dominant in the mark applied for and, thirdly, that the signs at issue are visually and conceptually similar.

– The distinctive character of the figurative elements of the earlier marks

47 It must be borne in mind that the distinctive character of the earlier mark is one of the factors to be taken into account when assessing the likelihood of confusion (Case T‑112/03 L’Oréal v OHIM — Revlon (FLEXI AIR) [2005] ECR II‑949, paragraph 61, and Case T‑134/06 Xentral v OHIM — Pages jaunes (PAGESJAUNES.COM) [2007] ECR II‑5213, paragraph 70; see also, to that effect and by analogy, Case C‑39/97 Canon [1998] ECR I‑5507, paragraph 24). In that context, it is necessary to distinguish between the notion of the distinctive character of the earlier mark, which determines the protection afforded to that mark, and the notion of the distinctive character which an element of a composite mark possesses, which determines its ability to dominate the overall impression created by the mark (order of 27 April 2006 in Case C‑235/05 P L’Oréal v OHIM, not published in the ECR, paragraph 43). While it is true that it is necessary to examine the distinctiveness of an element of a composite mark at the stage of assessing the similarity of the signs in order to determine any dominant element of the sign, the degree of distinctiveness of the earlier mark is an element to be taken into account in the context of the global assessment of the likelihood of confusion. It is therefore not appropriate to take account of what may be a low degree of distinctiveness of the earlier marks at the stage of assessing the similarity of the signs.

48 In the present case, the Board of Appeal found that the distinctive character of the figurative elements of the earlier marks was weak, given, in essence, that labels in the form of bands or ribbons, flags, or combinations of those elements are not uncommon on bottles containing alcoholic beverages, the intervener having provided examples of this.

49 The applicant counters that the earlier marks are distinctive per se. It is the only company to use the sign in question, namely a shape that corresponds to a tie, consisting in particular of the combination of a central element affixed at the junction of the knot and two ribbons parting from that knot, presented symmetrically.

50 In that regard, it must be stated at the outset, first, that the applicant admits that the earlier marks are figurative signs representing labels for affixing to bottle necks and, secondly, that those marks have been registered in respect of alcoholic beverages in Class 33.

51 Secondly, it must be stated that, by its argument, the applicant does not deny that affixing to a bottle of alcoholic beverage a label consisting of two bands intersecting at an angle with a circular element where the bands cross, which thus has the shape of a lavaliere tie, is a practice which exists in the sector in question. It maintains only that very few alcoholic beverages bottles manufactured by third parties exhibit those specific elements and that very few trade marks include that particular representation. It even admits that some marks filed by third parties use a similar figurative sign.

52 Furthermore, it is apparent from the file submitted to OHIM that the Board of Appeal did not err in finding that labels with that shape are not uncommon on bottles containing alcoholic beverages. During the administrative procedure, the intervener provided examples of marks, some of which were registered before the earlier marks, with a figurative element which also consisted of two bands intersecting at an angle with a circular element where the bands crossed. In that regard, it should be noted that, although, as the applicant in essence submits, some of those marks are above all used as labels on beer cans or are registered in respect of beer, which is excluded from the goods covered by the marks at issue in the present case, the fact remains that, in any event, the intervener did not only provide examples of marks to be used on beer bottles or for beer, but also marks which, having regard to their characteristics, relate to the goods covered by those signs, in particular wine. Lastly, the applicant errs in maintaining that those marks do not represent the shape of a tie, since the figurative elements of which they consist have a structure similar to that of the earlier marks, the figurative elements of which do indeed, according to the applicant, represent the shape of a tie.

53 Furthermore, it is apparent from the Annexes to the application, first, that affixing, to a bottle of champagne, a label consisting of two bands intersecting at an angle with an element where the bands cross does not appear uncommon and, secondly, that marks containing a figurative element based on a similar design have been registered for goods in Class 33. It is true that, in the examples provided in those annexes, the angle followed by the two bands may vary, to the point of sometimes reaching 180 degrees and thus constituting only a simple ring. Similarly, the bands may be longer or shorter and, more rarely, continue beyond the point of intersection, as is the case with the earlier marks and with marks held by the intervener. However, the mere fact that, in those marks, the bands continue beyond their point of intersection, thus conveying the image of a lavaliere-style tie, cannot confer on them a specific distinctive character, particularly because, as is apparent from those annexes and the evidence which the intervener provided during the administrative procedure, and as the applicant admits (see paragraph 51 above), similar representations are affixed to alcoholic beverages marketed by third parties.

54 The argument that the figurative sign has been used by the applicant since 1880 and that advertisements disseminated throughout the world for nearly a century show bottles bearing that sign is irrelevant, since it relates to distinctive character through use which the Board of Appeal did not primarily examine, on the ground that the applicant had not put it forward before the Opposition Division. Moreover, there is nothing which makes it possible to call into question the Board of Appeal’s statement, made for the sake of completeness, that the figurative elements contained in the earlier marks were only weakly distinctive, and therefore, even if they were found to have acquired an additional degree of enhanced distinctiveness through use, their total distinctiveness would still not be high.

55 Furthermore, as regards the distinctive character of the figurative element at issue, which was recognised during a procedure in Brazil, it is sufficient to state that, not only does the applicant refer, in that regard, merely to a legal opinion and not to an actual judicial decision, but also that, in any event, according to settled caselaw, first of all, the Community trade mark system is autonomous and, secondly, the legality of decisions of the Boards of Appeal is to be assessed purely by reference to Regulation No 207/2009 (see, to that effect, Case T‑122/99 Procter & Gamble v OHIM (soap bar shape) [2000] ECR II‑265, paragraphs 60 and 61; Case T‑32/00 Messe München v OHIM (electronica) [2000] ECR II‑3829, paragraphs 46 and 47; and T‑106/00 Streamserve v OHIM (STREAMSERVE) [2002] ECR II‑723, paragraph 66), with the result that the statements made in that procedure are irrelevant in the present case.

56 Lastly, the fact that the figurative elements of the earlier marks are not exclusively the necessary, generic or usual designation for those goods and are not used to designate one of their characteristics does not affect the foregoing findings, since the Board of Appeal did not base its conclusion as to the weak distinctive character of those elements on such considerations. Similarly, the fact, relied on by the applicant, that those elements may also have a decorative function when they fulfil the essential function of a trade mark is irrelevant in the present case and has not, moreover, been disputed by the Board of Appeal.

57 It follows from all of the foregoing that, in the alcoholic beverages sector, the use of labels consisting of two bands intersecting at an angle with a circular element where the bands cross is not uncommon.

58 The Board of Appeal did not therefore err in rejecting the applicant’s claim that the figurative element of the earlier marks was highly distinctive and in finding that that element was weakly distinctive.

– The dominant element of the mark applied for

59 It must be borne in mind that assessment of the similarity between two marks means more than taking just one component of a composite trade mark and comparing it with another mark. On the contrary, the comparison must be made by examining each of the marks in question as a whole, which does not mean that the overall impression conveyed to the relevant public by a composite trade mark may not, in certain circumstances, be dominated by one or more of its components (see OHIM v Shaker, paragraph 41 and the case-law cited). It is only if all the other components of the mark are negligible that the assessment of the similarity can be carried out solely on the basis of the dominant element (OHIM v Shaker, paragraph 42, and judgment of 20 September 2007 in Case C‑193/06 P Nestlé v OHIM, not published in the ECR, paragraph 42).

60 In the present case, the Board of Appeal found that the word element ‘dorato’ was the distinctive and dominant element of the mark applied for, which the applicant disputes.

61 In that regard, it should be borne in mind, first of all, that, according to settled case-law, where a trade mark is composed of word and figurative elements, the former are, in principle, more distinctive than the latter, because the average consumer will more readily refer to the goods in question by quoting the name of the trade mark than by describing its figurative element (Case T‑363/06 Honda Motor Europe v OHIM — Seat (MAGIC SEAT) [2008] ECR II‑2217, paragraph 30, and judgment of 31 January 2012 in Case T‑205/10 Cervecería Modelo v OHIM — Plataforma Continental (LA VICTORIA DE MEXICO), not published in the ECR, paragraph 38; see also, to that effect, Case T‑104/01 Oberhauser v OHIM — Petit Liberto (Fifties) [2002] ECR II‑4359, paragraph 47).

62 It is also apparent from the case-law that consumers usually describe and recognise wine by reference to the word element which identifies it, since that element designates in particular the grower or the estate on which the wine is produced (see, to that effect, Case T‑40/03 Murúa Entrena v OHIM − Bodegas Murúa (Julián Murúa Entrena) [2005] ECR II‑2831, paragraph 56, and Case T‑149/06 Castellani v OHIM — Markant Handels und Service (CASTELLANI) [2007] ECR II‑4755, paragraph 53). There is nothing to prevent that case-law, which was developed in relation to goods in Class 33, from being applicable to all the alcoholic beverages concerned in the present case.

63 Furthermore, it must be observed that the word element ‘dorato’ appears twice in the mark applied for. It appears, first, in the lower part of that mark, in the element representing a label for affixing to the body of a bottle, in large, black capital letters on a white background, surmounted by a coat of arms and stars; the word element ‘dorato’ itself surmounts the word element ‘metodo naturale di doppia fermentazione’, which is markedly smaller in size, and the whole is framed by borders and forms the shape of a shield. It appears, secondly, in the upper part of that mark, in the figurative element which represents a label for affixing to the neck of a bottle and consists of two intersecting bands, and, more specifically, at the intersection of those two bands; it is also written in black capital letters on a white background and is surmounted by a coat of arms and stars, and the whole is surrounded by golden borders forming a frame.

64 The figurative element representing a label for affixing to the neck of a bottle has a weak distinctive character, for the same reasons as those referred to in the context of the examination of the figurative elements of the earlier marks.

65 As regards the coats of arms in the mark applied for, it must be pointed out that, in view of where they are placed and their size, they constitute only a decorative element without any actual meaning. Consequently, that element is not capable of dominating the image which the relevant public will have of the mark applied for. The same is true of the stars situated below those coats of arms, the frames around the word element ‘dorato’ and the word element ‘metodo naturale di doppia fermentazione’, which appears in the lower part of the mark applied for, under the word element ‘dorato’, and in the upper part of the mark applied for, in the circular element at the end of the upper right-hand arm of the ‘x’ formed by the crossing of the two bands of which that part consists.

66 Consequently, the figurative elements contained in the mark applied for cannot constitute the dominant element in the overall impression created by that mark. By contrast, on account, in particular, of its position, its size, the fact that it appears twice in the mark applied for and the contrast between its black letters and the white background on which it appears, the word element ‘dorato’ constitutes the dominant element of that mark.

67 It follows from the foregoing that the Board of Appeal did not err in finding that the dominant and distinctive element of the mark applied for was the word element ‘dorato’.

68 Nevertheless, as the upper element of the mark applied for, which represents a label for affixing to the neck of a bottle, cannot be regarded as negligible, having regard, in particular, to its position and size, the assessment of the similarity between the signs cannot be carried out solely on the basis of the dominant element (see, to that effect, OHIM v Shaker, paragraph 42, and Nestlé v OHIM, paragraph 43).

– The visual comparison

69 The Board of Appeal found that the signs at issue were visually dissimilar.

70 The applicant counters by submitting that, in view of the presence of the figurative element representing a label in the signs at issue, those signs are visually similar.

71 In that regard, it must, first of all, be stated that the signs at issue have different structures. Thus, the mark applied for consists of two elements which are placed one above the other and are the same size. The lower part comprises a figurative element representing a label for affixing to the body of a bottle, consisting of the distinctive and dominant word element ‘dorato’ surmounted by a coat of arms and stars and surmounting the word element ‘metodo naturale di doppia fermentazione’, the whole of which is surrounded by a golden border forming a frame. The upper part comprises a figurative element representing a label for affixing to the neck of a bottle, which consists of two dark-coloured bands and golden borders, which intersect at an angle forming an ‘x’ and continue beyond that point of intersection, as well as a figurative element at that point, which represents, on a white background, a frame containing the word element ‘dorato’, a coat of arms and stars. By contrast, the earlier marks consist only of one part which contains, in essence, a figurative element representing a label for affixing to the neck of a bottle, consisting of two dark-coloured bands with a light or dark border, which intersect at an angle forming an ‘x’ and continue beyond that point of intersection, as well as a circular element at that point. Consequently, no element of the earlier marks is similar to the lower part of the mark applied for, which contains that mark’s dominant and distinctive element.

72 Furthermore, the only element of similarity between the marks at issue is that they have figurative elements representing a label for affixing to the neck of a bottle. It must be stated that, not only are those figurative elements weakly distinctive, as is apparent from the foregoing, but that, moreover, they contain many differences. Accordingly, in the earlier marks, there is a dark-coloured circular element at the intersection of the bands, whereas, in the mark applied for, it is an element representing, on a white background, a frame in the shape of a complex polygon containing the word element ‘dorato’, a coat of arms and stars. Furthermore, in the mark applied for, the upper right-hand part of the ‘x’ formed by the crossing of the two bands ends in a circular element which contains the word element ‘metodo natural di doppia fermentazione’, whereas, in the earlier marks, there is either no such element at the end or it appears in the upper left-hand part and contains, as regards one of those marks, the word element ‘m & c’ surmounted by a crown. Far from being an element of ‘symmetrical similarity’, as the applicant claims, it is an element of difference. Lastly, the word elements ‘m & c’, ‘réserve’, ‘impérial’ and ‘brut’ in some of the earlier marks are not in the mark applied for.

73 It follows from all of the foregoing that, viewed as whole, the signs at issue are visually different.

– The phonetic comparison

74 It must be pointed out that the applicant does not dispute the Board of Appeal’s assessment that the signs at issue are phonetically dissimilar.

75 Moreover, having regard to the word elements of those signs that assessment is correct.

– The conceptual comparison

76 The Board of Appeal found that, first, for Italian-speaking consumers, the mark applied for, which is dominated by the word element ‘dorato’, meant ‘gold’, whereas none of the word elements in the earlier marks conveyed that concept, and, secondly, for non-Italian speaking consumers, the mark applied for had no meaning, whereas the earlier marks contained laudatory elements, such as ‘brut’, ‘réserve’ or ‘impérial’. It therefore concluded that there was no conceptual similarity between the signs at issue.

77 The applicant counters that the figurative element in the signs at issue has a specific meaning, namely the representation of a tie to be affixed to bottle necks as a symbol of formal attire. It has chosen to use the motif in question in order to give to its bottles a formal, sophisticated and elegant livery which evokes the prestigious image of those goods. The mark applied for reproduces the same concept.

78 In that regard, it must be pointed out that the applicant has not put forward any arguments to dispute the specific assessments of the Board of Appeal concerning the conceptual meaning of the word elements of the signs at issue.

79 As for the presence in those signs of a figurative element representing a label in the shape of a tie, it must be borne in mind that, as has already been stated, first, that element is only weakly distinctive and, secondly, that consumers usually describe and recognise wine by reference to the word element which identifies it. They will not therefore attribute any specific conceptual meaning to the presence of the label in the shape of a tie.

80 Moreover, the applicant does not adduce any evidence to substantiate its claim that the figurative element in question will evoke a prestigious image of the goods concerned in the minds of consumers.

81 In any event, even if that claim were properly substantiated, the fact remains that that would not prove that the earlier marks have a ‘conceptual’ meaning, but would relate to the image conveyed by the goods to which they are affixed.

82 In those circumstances, it must be held that, assessed as a whole, the signs at issue are conceptually different.

The likelihood of confusion

83 A global assessment of the likelihood of confusion implies some interdependence between the factors taken into account, and in particular between the similarity of the trade marks and the similarity of the goods or services concerned. Accordingly, a lesser degree of similarity between those goods or services may be offset by a greater degree of similarity between the marks, and vice versa (Canon, paragraph 17, and Joined Cases T‑81/03, T‑82/03 and T‑103/03 MastJägermeister v OHIM — Licorera Zacapaneca (VENADO with frame and others) [2006] ECR II‑5409, paragraph 74).

84 The Board of Appeal found that, since the signs at issue are dissimilar overall, one of the conditions for the application of Article 8(1)(b) of Regulation No 207/2009 had not been satisfied, with the result that the opposition had to be rejected.

85 The applicant counters that, in view of the distinctive character per se and acquired through the use of the earlier marks, the identity of the goods at issue and the similarities between the signs at issue, there is a likelihood of confusion.

86 In this respect, it must be pointed out that, having regard to the fact that there is no visual, phonetic or conceptual similarity between the signs at issue, the Board of Appeal was right to find that those signs were dissimilar overall and that, consequently, one of the conditions for the application of Article 8(1)(b) of Regulation No 207/2009 had not been satisfied in the present case.

87 For the sake of completeness, it must be added that, even if the signs at issue were conceptually similar, that would have no bearing on the above finding. The more distinctive the earlier mark, the greater will be the likelihood of confusion. It is therefore not impossible that the conceptual similarity resulting from the fact that two marks use images with analogous semantic content may give rise to a likelihood of confusion where the earlier mark has a particularly distinctive character, either per se or because of the reputation it enjoys with the public. However, in circumstances such as those in the present case, where the earlier mark does not have a particularly distinctive character and consists of an image with little imaginative content, the mere fact that the marks are conceptually similar is not sufficient to give rise to a likelihood of confusion (see, to that effect, Case C‑251/95 SABEL [1997] ECR I‑6191, paragraphs 24 and 25).

88 It follows that the second plea must be rejected and consequently the action must be dismissed in its entirety.

Costs

89 Under Article 87(2) of the Rules of Procedure of the General Court, the unsuccessful party is to be ordered to pay the costs if they have been applied for in the successful party’s pleadings.

90 Since the applicant has been unsuccessful, it must be ordered to pay the costs, in accordance with the forms of order sought by OHIM and the intervener.

91 In addition, the intervener contends that the applicant should be ordered to pay the costs, including those incurred in the course of the proceedings before OHIM. In that regard, it should be borne in mind that, under Article 136(2) of the Rules of Procedure, costs necessarily incurred by the parties for the purposes of the proceedings before the Board of Appeal are to be regarded as recoverable costs. The same is not, however, true of costs incurred for the purposes of the proceedings before the Opposition Division. Accordingly, the intervener’s request that the applicant, having been unsuccessful, be ordered to pay the costs, including those incurred in the course of the proceedings before OHIM, can be allowed only as regards the costs necessarily incurred by the intervener for the purposes of the proceedings before the Board of Appeal.

On those grounds,

THE GENERAL COURT (Third Chamber)

hereby:

1. Dismisses the action;

2. Orders MHCS to pay the costs, including the costs necessarily incurred by Ambra SA for the purposes of the proceedings before the Board of Appeal of the Office for Harmonisation in the Internal Market (Trade Marks and Designs) (OHIM).

Papasavvas | Forwood | Bieliūnas |

Delivered in open court in Luxembourg on 9 April 2014.

[Signatures]