JUDGMENT OF THE COURT OF FIRST INSTANCE (Sixth Chamber)

10 October 2008 (*)

(Community trade mark – Application for registration of figurative Community trade mark representing a pallet – Absolute ground for refusal – Article 7(1)(b) of Regulation (EC) No 40/94)

In Joined Cases T‑387/06 to T‑390/06,

Inter-Ikea Systems BV, established in Delft (Netherlands), represented by J. Gulliksson, lawyer,

applicant,

v

Office for Harmonisation in the Internal Market (Trade Marks and Designs) (OHIM), represented by D. Botis, acting as Agent,

defendant,

ACTIONS brought against four decisions of the First Board of Appeal of the Office for Harmonisation in the Internal Market (Trade Marks and Designs) of 26 September 2006 (R 353/2006‑1, R 354/2006‑1, R 355/2006‑1 and R 356/2006‑1) concerning applications for the registration of four figurative trade marks consisting of graphic representations of a pallet,

THE COURT OF FIRST INSTANCE OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES (Sixth Chamber),

composed of A.W.H. Meij (Rapporteur), President, V. Vadapalas and L. Truchot, Judges,

Registrar: K. Pocheć, Administrator,

having regard to the applications lodged at the Registry of the Court of First Instance on 20 December 2006,

having regard to the responses lodged at the Registry of the Court on 27 March 2007,

having regard to the order of 4 June 2007 joining Cases T‑387/06 to T‑390/06,

having regard to the altered composition of the Chambers of the Court of First Instance,

having regard to the designation of another judge to complete the Chamber as one of its members was prevented from attending,

further to the hearing on 5 March 2008,

gives the following

Judgment

Background to the dispute

1 On 13 October 2004 the applicant, Inter-Ikea Systems BV, filed four applications for registration of a Community trade mark at the Office for Harmonisation in the Internal Market (Trade Marks and Designs) (‘the Office’), under Council Regulation (EC) No 40/94 of 20 December 1993 on the Community trademark (OJ 1994 L 11, p. 1), as amended.

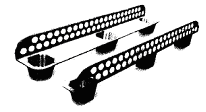

2 The trade mark applications concerned the following figurative signs:

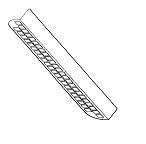

– in Case T‑387/06:

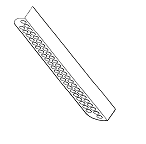

– in Case T‑388/06:

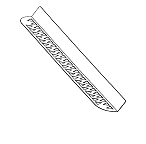

– in Case T‑389/06:

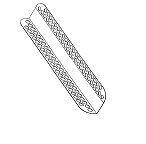

– in Case T‑390/06:

3 The goods and services in respect of which those applications for registration were made are in Classes 6, 7, 16, 20, 35, 39 and 42 of the Nice Agreement concerning the International Classification of Goods and Services for the Purpose of the Registration of Marks of 15 June 1957, as revised and amended, and correspond, in respect of each of those classes, to the following description:

– Class 6: ‘Common metals and their alloys; metal building materials; transportable buildings of metal; material of metal for railway tracks; non electric cables and wires; ironmongery, small items of metal hardware; pipes and tubes of metal; safes; goods of common metal, not included in other classes; ores; stretchers for iron bands (tension links); cross beams of metal; braces of metal for handling loads; containers of metal (storage, transportation); loading pallets of metal; loading carriers and loading pallets of metal for packaging and transportation purposes; loading gauge rods of metal; bins of metal; metal tension bands for handling loads; metal transport pallets’;

– Class 7: ‘Machines and machine tools; motors and engines (except for land vehicles); machine coupling and transmission components (except for land vehicles); agricultural implements other than hand-operated; incubators for eggs; packaging machines; carriers for machine tools; apparatus for loading and unloading goods’;

– Class 16: ‘Paper, cardboard and goods made from these materials not included in other classes; printed matter; bookbinding material; photographs; stationery; adhesives for stationery or household purposes; artists’ materials; paint brushes; typewriters and office requisites (except furniture); instructional and teaching material (except apparatus); plastic materials for packaging (not included in other classes); printers’ type; printing blocks; packaging paper; bottle packaging of cardboard or plastics; sealing material for stationery; storage boxes for stationery; covers (stationery); paper; plastic film for packaging; extensible plastic film for packing on pallets; shrink film of plastic for packaging and transportation purposes’;

– Class 20: ‘Furniture, mirrors, picture frames; goods (not included in other classes) of wood, cork, reed, cane, wicker, horn, bone, ivory, whalebone, shell, amber, mother-of pearl, meerschaum and substitutes for all these materials or of plastics; stretchers for iron bands (tension links) not of metal; braces not of metal for handling loads; packaging containers (packing) of plastic; packings of wood; containers not of metal for storage; closures for containers not of metal; containers not of metal (storage, transportations); goods pallets not of metal; loading pallets and loading carriers not of metal for packaging and transportation purposes; loading gauge rods not of metal for loading pallets; bins not of metal; transport pallets not of metal’;

– Class 35: ‘Professional business consultancy regarding packing, transport and storage economy; professional business consultancy regarding design, construction and use of load carriers’;

– Class 39: ‘Transport; packing, packaging and storage of articles and goods; porterage; freight forwarding; information regarding packaging, storage and transportation; advisory services regarding loading and packaging systems; professional consultation, non business, regarding packing, transport and storage economy; unloading of goods; storage of goods; transport brokerage; transporting furniture; packaging of articles and goods; shipping of goods; rental of storage containers; rental of loading pallets, loading carriers and handling equipment for loading; delivery of goods; information and advice regarding logistics’;

– Class 42: ‘Legal services; scientific, industrial and technical research; industrial analyses; computer programming; packaging and packing design; industrial design; research and development services regarding new products; copyright management; construction drafting; professional consultancy, non business, regarding design, construction and use of loading carriers; material testing; technical project studies; industrial and technical research; scientific and technological services and research and design related thereto; licensing of logistic services; patent exploitation; licensing of intellectual property’.

4 By four decisions of 20 January 2006 the examiner rejected the applications for registration on the basis of Article 7(1)(b) of Regulation No 40/94, on the ground that the trade marks applied for were devoid of any distinctive character.

5 On 10 March 2006 the applicant filed four notices of appeal against the examiner’s four decisions, under Articles 57 to 62 of Regulation No 40/94.

6 By four decisions of 26 September 2006 (‘the contested decisions’) the First Board of Appeal of the Office rejected the appeals on the ground that the trade marks applied for were devoid of any distinctive character within the meaning of Article 7(1)(b) of Regulation No 40/94.

Procedure and forms of order sought

7 During the oral procedure, the applicant stated to the Court that it had restricted the list of goods and services designated in the applications for trade mark registration, in accordance with Article 44(1) of Regulation No 40/94.

8 The applicant claims that the Court should:

– annul the contested decisions;

– order the Office to pay the costs.

9 The Office contends that the Court should:

– dismiss the actions;

– order the applicant to pay the costs.

Law

Arguments of the parties

10 The applicant relies on a single plea in law, alleging infringement of Article 7(1)(b) of Regulation No 40/94.

11 Primarily, the applicant claims that the trade marks are sufficiently distinctive to be registrable in respect of all the goods and services at issue listed in paragraph 3 above. In the alternative, it submits that the trade marks are, in any event, sufficiently distinctive to be registrable in respect of the goods and services in Classes 20, 35, 39 and 42, as listed in paragraph 3 above.

12 In support of its claims, the applicant denies that the trade marks applied for are faithful representations of the ‘Optiledge’ pallet represented below:

13 According to the applicant, they are stylised figurative marks with only some resemblance to that product, and there are significant differences between the trade marks sought and that product. The signs at issue do not include the three ‘feet’ positioned at the base of the product and have, on the flange, ornamental holes which are either square (Case T‑387/06), round (Cases T‑388/06 and T‑390/06), or triangular (Case T‑389/06), which give them aesthetic qualities. As regards the sign at issue in Case T‑390/06, there is also a large rectangular space between the holes on the base and on the flange. Furthermore, the forms shown in the trade mark applications do not correspond to objects which could function as a loading ledge. The trade marks applied for are therefore only suggestive of pallets.

14 The applicant claims that the Board of Appeal did not attach sufficient importance to the distinctive features of the trade marks sought, such as the round, square or triangular holes, and the gently curved edges on the flange and base, which make the signs sufficiently distinctive for the purposes of Article 7(1)(b) of Regulation No 40/94. The applicant adds that the distinctive character of the marks must be assessed in relation to the goods or services in respect of which registration is sought.

15 Furthermore, the applicant argues that, even if the marks applied for were to be considered faithful graphical representations of the product, those marks are none the less sufficiently distinctive to indicate commercial origin on account of the specific features referred to in paragraph 13 above, to which the Board of Appeal did not attach sufficient importance. Pursuing that argument, the applicant submits that it is necessary to ascertain, first, whether the design of the product represented may, in itself, make an impact on the public mind and, second, whether the way in which the product is represented has some distinctive feature capable of denoting the product’s origin. The applicant adds that, for the purposes of establishing the distinctive character of a figurative mark consisting of a representation of the product, the only relevant question is whether the representation is capable of being perceived by the relevant public as indicative of the product’s origin.

16 The Office considers, first, that the distinction made by the applicant between the primary claim and the subsidiary claim must be rejected as inadmissible or, if not, as clearly unfounded. The applicant has not put forward any explanation as to why the signs are more distinctive for the second set of goods and services than for the first set; its arguments are very general and fail to differentiate between the various goods and services designated. In addition, the subsidiary claim is meaningless since it is in any event contained within the primary claim and will therefore be examined in the assessment of the goods and services in their totality.

17 As regards the applicant’s argument that the trade marks applied for are not faithful representations of a pallet but, on the contrary, figurative marks, the Office considers that the differences between the trade marks sought and the pallet in question do not render that product unrecognisable, since the omitted or altered parts are only of secondary importance in the overall impression given by the product. The trade marks sought are technical drawings accurately depicting the shape of the product, which the relevant consumers will unequivocally recognise as some type of pallet or loading ledge.

18 The Office adds that, even where the shape for which protection is sought possesses certain individual features of form, these must still be of such a nature, kind and intensity, as to enable the sign to be perceived as an indicator of origin. Moreover, where the shape applied for essentially reproduces the necessary configuration of the goods, or resembles the shape most likely to be taken by them, it is for the applicant to prove that it departs significantly from the norm or customs of the sector in such a manner that it will be perceived by the public as indicating origin.

19 The Office considers that the Board of Appeal examined the signs at issue in detail and correctly held that the differences between them and the pallet were no more than banal shapes, which would not be spontaneously recognised by the relevant public. The Board of Appeal was therefore correct in finding that the signs at issue consisted of the shape of the product, since they faithfully reproduced the shape of a pallet.

20 As regards establishing whether the signs at issue are distinctive having regard to the goods and services for which the applications for registration were made, the Office points out that in the contested decisions the Board of Appeal examined the category of relevant goods and services, established the relevant customer profile and level of attention and cited numerous examples concerning the expected consumer reaction to the sign. The Board of Appeal thus established that the marks applied for were perceived by the relevant public as the shape of a pallet and not as denoting the commercial origin of goods or services in the sectors related to pallets, directly or indirectly. It is, according to the Office, for the applicant to prove that that finding did not apply in respect of some of the goods or services designated.

21 The Office adds that the public is not accustomed to recognising the origin of goods by virtue of the pallet on which they are stored, nor that of transport or storage services on the basis of the type of equipment used. Likewise, the public would not perceive the technical drawing of a pallet as a trade mark denoting the origin of designer services or legal services in the field of intellectual property.

22 In addition, according to the Office, the applicant does not question the quality or the completeness of the reasoning of the Board of Appeal in the contested decisions under Articles 73 and 74 of Regulation No 40/94, but alleges only that there were errors of assessment and an infringement of Article 7(1)(b) of Regulation No 40/94. At the hearing, the Office added that the Court of Justice permits general reasoning for all of the goods and services concerned where the same ground of refusal is given for a category or group of goods or services (Case C‑239/05 BVBA Management, Training en Consultancy [2007] ECR I‑1455, paragraph 37).

23 The Office concludes that the Board of Appeal rightly considered the trade marks applied for to be devoid of any distinctive character in respect of all the goods and services for which protection was sought, so that they are not eligible for registration, in accordance with Article 7(1)(b) of Regulation No 40/94.

Findings of the Court

24 First, it must be noted that, during the oral procedure, the applicant informed the Court that, in accordance with Article 44(1) of Regulation No 40/94, it had withdrawn from the list of goods and services covered in the applications for trade mark registration reference to ‘loading gauge rods not of metal for loading pallets’, in Class 20.

25 A restriction carried out in accordance with Article 44(1) of Regulation No 40/94 subsequent to the adoption of the contested decision may be taken into consideration by the Court where the applicant for the trade mark limits itself strictly to reducing the subject-matter of the dispute by withdrawing certain categories of goods or services from the list of goods and services covered in the trade mark application (Case T‑325/04 Citigroup v OHIM – Link Interchange Network (WORLDLINK), not published in ECR, paragraph 26).

26 In the present case, since the restriction of goods and services covered in the trade mark applications simply reduces the subject-matter of the dispute, it is unnecessary to examine the lawfulness of the contested decisions in so far as they concern the distinctiveness of the signs in question in relation to ‘loading gauge rods not of metal for loading pallets’, in Class 20.

27 As to the substance, under Article 7(1)(b) of Regulation No 40/94 ‘trade marks which are devoid of any distinctive character’ are not to be registered. A mark which enables the goods or services in respect of which registration of the mark has been sought to be distinguished as to their origin has distinctive character within the meaning of that provision. It is not necessary for that purpose for the mark to convey exact information about the identity of the manufacturer of the product or the supplier of the services. It is sufficient that the mark enables members of the public concerned to distinguish the product or service that it designates from those which have a different trade origin and to conclude that all the products or services that it designates have been manufactured, marketed or supplied under the control of the owner of the mark and that the owner is responsible for their quality (Case T‑337/99 Henkel v OHIM (White and red round tablet) [2001] ECR II‑2597, paragraph 43; see also, to that effect and by analogy, Case C‑39/97 Canon [1998] ECR I‑5507, paragraph 28).

28 The distinctive character of a mark must be assessed, first, in relation to the goods or services for which registration of the sign has been requested and, second, in relation to the perception of the relevant public, consumers who are reasonably well informed and reasonably observant and circumspect (Case T‑63/01 Procter & Gamble v OHIM (Soap shape) [2002] ECR II‑5255, paragraph 39; see also, by analogy, Joined Cases C‑53/01 to C‑55/01 Linde and Others [2003] ECR I‑3161, paragraph 41).

29 It is clear from the case-law that the criteria for assessing the distinctive character of marks consisting of the graphic representation of the product itself are no different from those applicable to other categories of trade marks. However, when those criteria are applied, account must be taken of the fact that the perception of the relevant section of the public is not necessarily the same in relation to a mark consisting of a faithful representation of the product itself as it is in relation to a word mark or a figurative or three-dimensional mark not faithfully representing the product. Whilst the public is used to recognising the latter marks instantly as signs identifying the product, this is not necessarily so where the sign is indistinguishable from the appearance of the product itself (Case T‑30/00 Henkel v OHIM (Image of a detergent product) [2001] ECR II‑2663, paragraph 49). It can therefore prove more difficult to establish the distinctive character of a mark consisting of the faithful representation of the product itself than that of a word mark, or a figurative or three-dimensional mark which does not faithfully represent the product (see, to that effect, Case C 24/05 P Storck v OHIM [2006] ECR I‑5677, paragraph 25).

30 In those circumstances, only a mark which departs significantly from the norm or customs of the sector and thereby fulfils its essential function of indicating origin is not devoid of distinctive character for the purposes of Article 7(1)(b) of Regulation No 40/94, (Storck v OHIM, paragraph 26).

31 In the present case, the applicant has not challenged the Board of Appeal’s assessment that the relevant public for the goods and services in respect of which registration of the trade marks is sought consists of professionals and consumers.

32 It must next be observed that the figurative signs for which the protection of the Community trade mark is sought consistent of graphic representations of one of the main elements of a loading pallet named ‘OptiLedge’, reproduced in paragraph 12 above, a product whose design and appearance differ from those of traditional loading pallets, made of wood. As the Board of Appeal observed in the contested decisions, those signs consist of graphic representations of elongated rectangular platforms or bases with a flange of the same length (Cases T‑387/06 to T‑389/06) or longer (Case T-390/06) at a 90 degree angle to the base; the flange is ornamented with holes which are either square (Case T‑387/06), round (Cases T‑388/06 and T‑390/06), or triangular (Case T‑389/06) (see paragraph 2 above).

33 In order to examine the lawfulness of the contested decisions, a distinction must be made within the goods and services designated in the registration applications, according to whether they are (i) loading pallets or goods directly associated with loading pallets or (ii) unrelated to loading pallets.

34 As regards, first, goods and services designated in the registration applications which are loading pallets or items directly associated with those goods, namely ‘loading pallets of metal’, ‘loading carriers and loading pallets of metal for packaging and transportation purposes’ and ‘metal transport pallets’, in Class 6; ‘goods pallets not of metal’, ‘loading pallets and loading carriers not of metal for packaging and transportation purposes’ and ‘transport pallets not of metal’, in Class 20; and the services of ‘rental of loading pallets’, in Class 39, it must be observed, at the outset, that no specific information is provided as to the types of loading pallets in question, and accordingly it must be considered that all types of loading pallets are covered by those applications for registration.

35 It must next be observed that, while the graphic representations in question in the registration applications faithfully reproduce the appearance of one of the main elements of the ‘OptiLedge’ pallet, they do not represent that loading pallet in its entirety, which comprises, as can be seen in paragraph 12 above, at least two main elements each of which has three feet under the rectangular base. As the applicant claims, the marks applied for cannot therefore be regarded as faithful representations of a pallet intended for moving or storing goods.

36 It is however clear that, to the extent that those graphic representations exactly reproduce the shape of one of the main elements of the product which they are to designate or of the product to which the services referred to in paragraph 34 above relate, namely a pallet potentially designed in the same way as the ‘OptiLedge’ pallet, those signs cannot distinguish the goods and services at issue as regards their commercial origin. As the Board of Appeal comments in paragraph 24 of the contested decisions, the signs applied for are a representation of a shape which is likely to be commonly used in trade, since, for technical reasons, use will necessarily be made of that shape whenever loading pallets of the pallet type known as ‘OptiLedge’ are required. For that reason, the relevant public will often encounter that shape, which, since it is likely to appear on pallets with a variety of commercial origins, will be incapable of indicating the commercial origin of the designated goods and services referred to in paragraph 34 above.

37 The applicant’s claim that the graphic representations in question show clear differences from the ‘OptiLedge’ pallet, cannot, even if substantiated, affect that finding. The Board of Appeal rightly noted that the features in which those differences reside, such as the square, round or triangular shaped holes, or even, in relation to Case T‑390/06, the rectangular space between the holes and the flange, are banal and add no distinctive character to the graphic representations. Consequently, the applicant’s argument that the marks applied for draw their distinctive character from that of the appearance of the product itself, to the extent that the product presents the features described above, cannot succeed.

38 The Board of Appeal therefore purposely considered the signs in question to be devoid of any distinctive character within the meaning of Article 7(1)(b) of Regulation No 40/94, in so far as they relate to ‘loading pallets of metal’, ‘loading carriers and loading pallets of metal for packaging and transportation purposes’ and ‘metal transport pallets’ in Class 6; the ‘goods pallets not of metal’, ‘loading pallets and loading carriers not of metal for packaging and transportation purposes’ and ‘transport pallets not of metal’ in Class 20; and ‘rental of loading pallets’ services, in Class 39.

39 As regards, secondly, the remaining goods and services designated in the registration applications, which are unrelated to loading pallets, it must be noted that, in paragraph 20 of the contested decisions, the Board of Appeal stated that ‘the mark applied for depicts a faithful graphic representation of a pallet which is purposely aimed at moving or storing goods’. The Board of Appeal consequently decided that, in relation to all of the goods and services, the signs for which registration was sought would be treated as ‘faithful graphic representation[s] for the goods and services applied for’.

40 Moreover, in paragraph 24 of the contested decisions, the Board of Appeal stated that ‘the graphic representation[s] of the shape of a pallet [are] usual and [have] no special characteristics likely to distinguish this shape from others’. Again, in paragraph 26 of the contested decisions, the Board of Appeal observed that ‘the average customer in the relevant market … will perceive the mark applied for merely as a simple pallet device and not as an indication of trade origin’.

41 Those considerations make it clear that the Board of Appeal confined itself to examining the distinctive character of the marks applied for solely in relation to pallets, and did not carry out an examination of distinctive character in relation to all of the goods and services designated in the trade mark registration applications. An examination of the grounds for refusal referred to in Article 7 of Regulation No 40/94 must be carried out in relation to each of the goods or services for which trade mark registration is sought. Furthermore, the decision of the Office refusing registration of a trade mark must, in principle, state reasons in respect of each of those goods or services (see, to that effect and by analogy, BVBA Management, Training en Consultancy, paragraph 34).

42 In that regard, while the competent authority may use only general reasoning for all of the goods or services concerned where the same ground of refusal is given for a category or group of goods or services (BVBA Management, Training en Consultancy, paragraph 37), that does not apply in this case. As stated in paragraphs 39 to 41 above, it is clear from the contested decisions that the Board of Appeal confined itself to examining the distinctive character of the marks applied for solely in relation to pallets, and did not, even in general terms, proceed to an examination of distinctive character in relation to the other goods and services designated in the trade mark registration applications. Consequently, the Office cannot claim that the contested decisions contain general reasoning for all of the goods in question which are unrelated to loading pallets.

43 The Court must also reject the Office’s assertion that it was for the applicant to prove that the conclusion that the signs in question were devoid of any distinctive character was not applicable to those goods and services. Suffice it to point out, in that regard, that it fell to the Board of Appeal in the first place to establish that, in relation to those goods and services, the signs in question did not significantly depart from the norm or customs of the sector (see paragraph 30 above).

44 It must therefore be held that, by failing to examine the distinctive character of the marks applied for in relation to each of the goods and services covered by the application, the Board of Appeal infringed Article 7(1)(b) of Regulation No 40/94 in relation to designated goods other than loading pallets.

45 In light of all the foregoing considerations, it must be concluded that the contested decisions must be annulled in so far as the Board of Appeal’s finding that the marks applied for were devoid of any distinctive character, within the meaning of Article 7(1)(b) of Regulation No 40/94 related to all of the goods and services in Classes 6, 7, 16, 20, 35, 39, and 42, referred to in paragraph 3 above (as restricted in accordance with Article 44(1) of Regulation No 40/94) but not in so far as that finding related to ‘loading pallets of metal’, ‘loading carriers and loading pallets of metal for packaging and transportation purposes’ and ‘metal transport pallets’, in Class 6; ‘goods pallets not of metal’, ‘loading pallets and loading carriers not of metal for packaging and transportation purposes’ and ‘transport pallets not of metal’, in Class 20; and the ‘rental of loading pallets’ services, in Class 39.

Costs

46 Under Article 87(3) of its Rules of Procedure, where each party succeeds on some and fails on other heads, the Court of First Instance may order that each party bear its own costs. In the present case, since the actions have been partially upheld, it is appropriate to decide that each party should bear its own costs.

On those grounds,

THE COURT OF FIRST INSTANCE (Sixth Chamber)

hereby:

1. Annuls the decisions of the First Board of Appeal of the Office for Harmonisation in the Internal Market (Trade Marks and Designs) (OHIM) of 26 September 2006 (R 353/2006-1, R 354/2006-1, R 355/2006‑1 and R 356/2006-1) in so far as registration of the marks applied was refused in respect of goods and services in Classes 6, 7, 16, 20, 35, 39 and 42 of the Nice Agreement concerning the International Classification of Goods and Services for the Purpose of the Registration of Marks of 15 June 1957, as revised and amended but not in so far as that refusal was in respect of ‘loading pallets of metal’, ‘loading carriers and loading pallets of metal for packaging and transportation purposes’ and ‘metal transport pallets’, in Class 6; ‘goods pallets not of metal’, ‘loading pallets and loading carriers not of metal for packaging and transportation purposes’ and ‘transport pallets not of metal’, in Class 20; and the ‘rental of loading pallets’ services, in Class 39.

2. Dismisses the actions as to the remainder.

3. Orders each party to bear its own costs.

Delivered in open court in Luxembourg on 10 October 2008.