JUDGMENT OF THE GENERAL COURT (Sixth Chamber)

6 June 2013 (*)

(Community design – Invalidity proceedings – Community design representing watch dials – Earlier unregistered designs – Ground for invalidity – Novelty – Articles 4, 5 and 25(1)(b) of Regulation (EC) No 6/2002 – Individual character – Different overall impression – Articles 4, 6 and 25(1)(b) of Regulation No 6/2002 – Earlier copyright – Article 25(1)(f) of Regulation No 6/2002)

In Case T‑68/11,

Erich Kastenholz, residing in Troisdorf (Germany), represented by L. Acker, lawyer,

applicant,

v

Office for Harmonisation in the Internal Market (Trade Marks and Designs) (OHIM), represented initially by S. Hanne, and subsequently by D. Walicka, acting as Agents,

defendant,

the other party to the proceedings before the Board of Appeal of OHIM, intervener before the General Court, being

Qwatchme A/S, established in Løsning (Denmark), represented by M. Zöbisch, lawyer,

ACTION brought against the decision of the Third Board of Appeal of OHIM of 2 November 2010 (Case R 1086/2009‑3) concerning invalidity proceedings between Erich Kastenholz and Qwatchme A/S,

THE GENERAL COURT (Sixth Chamber),

composed of H. Kanninen (President), S. Soldevila Fragoso (Rapporteur) and A. Popescu, Judges,

Registrar: S. Spyropoulos, Administrator,

having regard to the application lodged at the Registry of the General Court on 25 January 2011,

having regard to the response of OHIM lodged at the Registry of the General Court on 17 May 2011,

having regard to the response of the intervener lodged at the Registry of the General Court on 6 May 2011,

having regard to the change in the composition of the Chambers of the General Court,

further to the hearing on 8 November 2012,

gives the following

Judgment

Background to the dispute

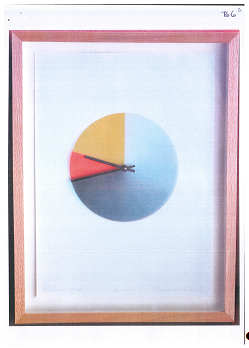

1 On 28 September 2006, the intervener, Qwatchme A/S, filed an application for registration of a Community design with the Office for Harmonisation in the Internal Market (Trade Marks and Designs) (OHIM), pursuant to Council Regulation (EC) No 6/2002 of 12 December 2001 on Community designs (OJ 2002 L 3, p. 1).

2 The design for which registration was sought is represented, in black and white, as follows:

3 The design referred to in paragraph 2 above was registered on the very day the application for registration was made, under number 000602636‑0003 (‘the contested design’). The products to which the design is intended to be applied fall within Class 10.07 of the Locarno Agreement Establishing an International Classification for Industrial Designs of 8 October 1968 and correspond to the following description: ‘Watch dials, parts of watch dials, hands of dials’.

4 On 25 June 2008, the applicant, Mr Erich Kastenholz, lodged with OHIM an application for a declaration of invalidity of the contested design, pursuant to Article 52 of Regulation No 6/2002. The grounds invoked in support of the application for a declaration of invalidity were, firstly, that referred to in Article 25(1)(b) of Regulation No 6/2002, that the contested design did not satisfy the requirements for protection in Articles 4 and 5 of the regulation because of its lack of novelty and, secondly, that referred to in Article 25(1)(f) of the regulation, that the contested design constituted an improper use of a dial protected by German copyright law.

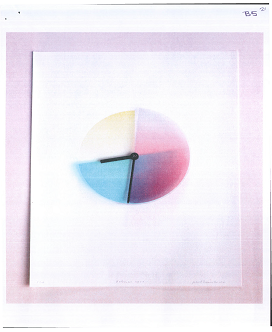

5 The applicant claimed, in particular, that the contested design was identical to the design of a dial, protected by German copyright law, that used the technique of the superposition of coloured discs ‘Farbfolge II, 12 Stunden im 5-Minuten Takt’ (Sequence of colours II, 12 hours in a cadence of 5 minutes), exhibited and published by the artist Paul Heimbach between 2000 and 2005, which is represented, in colour and in black and white respectively, as follows:

‘Farbfolge II, 12 Stunden im 5-Minuten Takt’ (in colour)

‘Farbfolge II’ (2003) (in black and white)

6 It is from the design ‘Farbfolge II, 12 Stunden im 5-Minuten Takt’ that the artist Paul Heimbach developed the dial ‘Farbzeiger II’, which is represented, in black and white, as follows:

7 The applicant also claimed that ‘Farbfolge II, 12 Stunden im 5-Minuten Takt’, ‘Farbfolge II’ (2003) and ‘Farbzeiger II’ were protected by German copyright law as they ‘depict[ed] a dial that changed continuously with the movement of the hands and in which each hand was fixed to a coloured, semi-transparent disc that generated different colours each time the hands were superposed [on each other]’.

8 In his additional written statement of 27 October 2008 before the Invalidity Division of OHIM, the applicant claimed, so far as concerned the requirements of novelty and of individual character in Article 4 of Regulation No 6/2002, that the contested design had the same features as the design ‘Farbfolge II, 12 Stunden im 5-Minuten Takt’, as shown in colour and in black and white in paragraph 5 above. He also put before OHIM two original pieces from the works of Paul Heimbach, namely, ‘Farbfolge (5/17)’ [Sequence of colours (5/17)], signed and dated February 2000, and ‘Farbfolge II (89/100)’ [Sequence of colours II (89/100)], signed and dated September 2003, which constitute variants of the design ‘Farbfolge II, 12 Stunden im 5-Minuten Takt’ initially put forward by the applicant, and which are represented, respectively, as follows:

‘Farbfolge (5/17)’

‘Farbfolge II (89/100)’

9 The various representations, developments and variants of ‘Farbfolge II, 12 Stunden im 5-Minuten Takt’ referred to in paragraphs 5, 6 and 8 above constitute both the designs examined in the course of the invalidity proceedings before OHIM (‘the earlier designs’) and the works of art examined in those proceedings (‘the earlier works of art’).

10 By decision of 16 July 2009, the Invalidity Division rejected the application for a declaration of invalidity, holding that the contested design and the earlier designs were distinct because of the differences between the discs. It based this finding on the fact that, firstly, none of the configurations shown in the respective views of the contested design appearing in any of the earlier designs, the latter could not, therefore, constitute an obstacle to the novelty of the contested design, and that, secondly, the earlier designs produced a wide array of different colours, while the contested design produced a maximum of three shades of colour only. [The contested design] therefore produced a different impression from that created by the earlier designs, and this made it possible to recognise the contested design as having individual character. In addition, the Invalidity Division found that, because of the differences between the designs in question, the contested design did not make use of the work protected by German copyright.

11 On 25 October 2009, the applicant filed a notice of appeal at OHIM, pursuant to Articles 55 to 60 of Regulation No 6/2002, against the decision of the Invalidity Division.

12 By decision of 2 November 2010 (‘the contested decision’), the Third Board of Appeal dismissed the appeal, finding, first of all, that the contested design was different from the earlier designs inasmuch as the colours of the dial shown in the designs at issue differed widely one from the other and produced a different overall impression on the informed user. It stated that, consequently, the contested design possessed individual character and could not, therefore, be identical to the earlier designs for the purposes of Article 5 of Regulation No 6/2002. It found, secondly, that because of the differences between the designs at issue, the contested design could not be regarded as being either a reproduction or an adaptation of the earlier works of art.

Forms of order sought

13 The applicant claims that the Court should:

– annul the contested decision;

– remit the case for the purpose of the consideration of copyright protection;

– order OHIM to pay the costs.

14 OHIM and the intervener contend that the Court should:

– dismiss the action;

– order the applicant to pay the costs.

15 At the hearing, the applicant withdrew his second head of claim, formal note of which was taken in the minutes of the hearing.

Law

The applicant’s request that an expert opinion be obtained

16 The applicant requests the Court to permit a professor of art to take part as an expert in the proceedings, in order to establish that the original idea underlying the earlier works of art, namely, the representation of time through different colours and shades, enjoys copyright protection and to give the expert, where appropriate, the opportunity to provide, at the hearing, explanations additional to the expert’s report submitted during the administrative procedure.

17 OHIM takes the view that there is no need to allow a professor of art to take part, as expert, in the proceedings before the Court, for the observations set out in the expert’s report are not relevant for the purpose of establishing whether those works of art have to be protected against the registration of the contested design.

18 The intervener takes the view that the request that an expert opinion be obtained, as sought by the applicant, is irrelevant.

19 It should be pointed out that its Rules of Procedure confer on the General Court a discretionary power to decide whether or not to order a measure such as the commissioning of an expert’s report. Under Article 65 of those Rules, the Court may order the commissioning of an expert’s report, either of its own motion or on application by a party. Where a request for an expert’s report, made in the application, indicates precisely the reasons why such a measure should be ordered, it is for the Court to assess the relevance of that request in relation to the subject-matter of the dispute and to the need to order such a measure.

20 In circumstances such as those of this case, the work of the professor of art, as expert, would be confined to examining the factual circumstances of the dispute and to giving a qualified opinion on them, on the basis of his or her professional skills.

21 However, whether or not copyright protection exists for the original idea underlying a work of art is an assessment of a legal nature which, in the context of the present proceedings, does not fall within the competence of an expert on art.

22 Therefore, the applicant’s request must be rejected.

Admissibility of the applicant’s arguments raised for the first time before the Court

23 OHIM contends that the applicant’s factual explanations as to the relevant market sector were not submitted during the proceedings before the Board of Appeal and may not be pleaded for the first time before the Court.

24 By those arguments, the applicant attempts to demonstrate the trend in the decorative watch sector, in which the principle of the dial that changes colour was developed, for the first time, in the earlier designs, which the applicant considers important in order to assess the overall impression produced on the informed user by the designs at issue.

25 As set out in Article 135(4) of the Rules of Procedure, the parties’ pleadings may not change the subject-matter of the proceedings before the Board of Appeal. It is for the Court, in the present case, to review the legality of decisions taken by the Boards of Appeal. Consequently, the Court’s review cannot go beyond the factual and legal context of the dispute as it was brought before the Board of Appeal (see, to that effect and by analogy, Case T‑66/03 ‘Drie Mollen sinds 1818’ v OHIM – Nabeiro Silveira (Galáxia) [2004] ECR II‑1765, paragraph 45). Likewise, the applicant does not have the power to alter before the Court the terms of the dispute as delimited in the respective claims and allegations submitted by him and by the intervener (see, to that effect and by analogy, Case C‑412/05 P Alcon v OHIM [2007] ECR I‑3569, paragraph 43, and Case C‑16/06 P Les Éditions Albert René v OHIM [2008] ECR I‑10053, paragraph 122).

26 Contrary to what OHIM contends, the argument raised by the applicant is not intended to re-examine the factual background to the dispute in the light of the factual explanations submitted for the first time before the Court, but constitutes a development of his line of argument intended to establish that the contested design does not have individual character inasmuch as it constitutes a reproduction of a new idea or principle developed for the first time in the earlier designs (see, to that effect and by analogy, Alcon v OHIM, paragraph 40).

27 Admittedly, the documents before the Court show that the argument referred to above was not raised before the Board of Appeal. Nevertheless, it is apparent from the application that the argument in question develops the line of argument that the contested design does not have individual character, according to which the contested design is merely a reproduction of the earlier designs whose original idea or principle was to show the changing hours through the changing of the colours of the watch dial. That line of argument, which seeks to challenge the possibility of the contested design’s being granted protection under Article 4 of Regulation No 6/2002 on the basis of its lack of novelty and individual character, had already been put forward by the applicant during the administrative procedure. Thus, the applicant claimed before the Invalidity Division, in the context of the application of Article 4 of Regulation No 6/2002, and in his reply to the observations made by the intervener before the Court, contained in his additional written statement of 27 October 2008, that the contested design had exactly the same features as the works of the artist Paul Heimbach. He also maintained before the Board of Appeal, with respect to the application of Article 25(1)(b) of Regulation No 6/2002, that the designs at issue showed two or three surfaces coloured in the same way and that they produced, therefore, the same overall impression. Contrary to what OHIM contends, and despite their succinctness, those explanations permit the inference that the argument that the contested design does not have individual character had already been raised in the application for a declaration of invalidity submitted by the applicant.

28 That argument is, therefore, admissible.

Substance

29 The applicant submits three pleas in law in support of his action. The first alleges infringement of Articles 4 and 5, read in conjunction with Article 25(1)(b), of Regulation No 6/2002; the second, infringement of Articles 4 and 6, read in conjunction with Article 25(1)(b), of the regulation; and the third, infringement of Article 25(1)(f) of the regulation.

First plea, alleging infringement of Articles 4 and 5, read in conjunction with Article 25(1)(b), of Regulation No 6/2002

30 The applicant submits that, in the contested decision, the Board of Appeal relied essentially on the individual character of the contested design and that its examination of novelty was inadequate. The Board of Appeal thus did not clearly distinguish those two factors.

31 The applicant claims that novelty must be interpreted objectively and that, under Article 5 of Regulation No 6/2002, the only matter to be determined is whether the contested design is identical to the earlier designs that were made available to the public before the date on which the application for registration was filed. In addition, he states that this identity or, in the language of Article 5(2) of Regulation No 6/2002, ‘identi[[ty] except in] immaterial details’ cannot be equated with the identity of the overall impression produced by the designs at issue, as examined for the purpose of assessing the individual character of the contested design under Article 6 of Regulation No 6/2002.

32 OHIM and the intervener dispute the applicant’s arguments.

33 Under Article 4(1) of Regulation No 6/2002, [a design is to be] protected by a Community design to the extent that it is new and has individual character.

34 As set out in Article 5(1)(b) of the regulation, a registered Community design is to be considered to be new if no identical design has been made available to the public ‘before the date of filing of the application for registration of the design for which protection is claimed, or, if priority is claimed, the date of priority’.

35 In the present case, it is clear from paragraph 23 of the contested decision that the earlier designs were made available to the public before 28 September 2006, the date on which the application for registration of the contested design was filed with OHIM, a fact which has not been disputed by the parties.

36 The Board of Appeal stated, in paragraph 27 of the contested decision, that novelty and individual character were separate requirements, although they overlapped to some extent. Thus, it found that if two designs produced a different overall impression on the informed user, they could not be regarded as being identical for the purposes of assessing the novelty of the later design.

37 According to Article 5(2) of Regulation No 6/2002, two designs are to be deemed to be identical if their features differ only in immaterial details, that is to say, details that are not immediately perceptible and that would not therefore produce differences, even slight, between those designs. A contrario, for the purpose of assessing the novelty of a design, it is necessary to assess whether there are any, even slight, non-immaterial differences between the designs at issue.

38 As the applicant claims, the wording of Article 6 goes beyond that of Article 5 of Regulation No 6/2002. Consequently, the differences observed between the designs at issue in the context of Article 5 may, especially if they are slight, not be sufficient to produce on an informed user a different overall impression within the meaning of Article 6 of Regulation No 6/2002. In that case, the contested design may be regarded as being new within the meaning of Article 5 of Regulation No 6/2002, but will not be regarded as having individual character within the meaning of Article 6 of the regulation.

39 By contrast, to the extent that the requirement laid down in Article 6 of Regulation No 6/2002 goes beyond that laid down in Article 5 of the regulation, a different overall impression on the informed user within the meaning of Article 6 can be based only on the existence of objective differences between the designs at issue. Those differences must therefore be sufficient to satisfy the requirement of novelty in Article 5 of Regulation No 6/2002, in accordance with what has been stated in paragraph 37 above. Consequently, as the Board of Appeal stated in paragraph 27 of the contested decision, the requirements of novelty and individual character overlap to some extent.

40 In the present case, the designs at issue are not identical within the meaning of Article 5 of Regulation No 6/2002. As the Board of Appeal stated in paragraph 25 of the contested decision, the earlier designs are characterised by the graded sequence of a wide spectrum of colours, the combination and intensity of which changes with the hour, whereas the contested design has only two uniform shades or colours in the 12 o’clock and 6 o’clock positions or four uniform shades in the positions showing the other hours and, therefore, in each case, there is no variation in the intensity of the shades. Those details constitute, from an objective point of view and irrespective of their consequences for the overall impression produced on the informed user, significant differences between the designs at issue, which make it possible to recognise the novelty of the contested design.

41 That conclusion is not called into question by the applicant’s argument that the design ‘Farbfolge (5/17)’, reproduced in paragraph 8 above, is composed of two discs that are only half coloured and that ought therefore to have the same effect as the two half-discs composing the contested design.

42 The differences between the contested design and the earlier design ‘Farbfolge (5/17)’ do not arise from the fact that the coloured discs that form part of each of those designs are half-discs or whole discs that are half coloured, but from the way in which they have been coloured. As is apparent from paragraph B2 of the decision of the Invalidity Division, summarised in paragraph 10 of the contested decision, in the case of the earlier designs ‘Farbfolge (5/17)’ and ‘Farbfolge II (89/100)’, reproduced in paragraph 8 above, the discs have been coloured with a clockwise increasing intensity, whereas in the case of the contested design, the discs have been coloured uniformly. In addition, those two [earlier] designs comprise a third disc that is not present in the contested design and which also contributes to producing a different visual effect from that produced by the contested design. As is apparent from paragraphs B1 and B2 of the decision of the Invalidity Division and from paragraph 25 of the contested decision, those features are present in each of the earlier designs and give rise to the graded sequence of a wide spectrum of colours, the combination and intensity of which changes with the hour. That sequence constitutes the characteristic feature of the earlier designs, irrespective of whether the coloured discs that form part of each of those designs are half-discs or whole discs that are half coloured.

43 The Board of Appeal therefore correctly determined, in paragraph 25 of the contested decision, the differences between the designs at issue enabling it to assess the novelty of the contested design, and was correct to conclude that it was new.

44 The applicant alleges that the Board of Appeal failed, in assessing the novelty of the contested design on the basis of the details referred to in paragraph 40 above, to compare views 3.1 to 3.7 of that design (represented in paragraph 2 above) with one of the earlier designs, namely ‘Farbfolge II, 12 Stunden im 5-Minuten Takt’ (represented in colour in paragraph 5 above), when it concluded that the designs at issue are not identical with the result that it made a procedural error. According to the applicant, the comparison of the contested design and the earlier design ‘Farbfolge II, 12 Stunden im 5-Minuten Takt’ shows that all the representations of the dials are almost the same in each case, the only difference being that in the earlier design in question, the boundaries between the colours are slightly softer.

45 However, it is apparent from paragraph 25 of the contested decision that the Board of Appeal did compare the contested design to the earlier design ‘Farbfolge II, 12 Stunden im 5-Minuten Takt’ represented in colour in paragraph 5 above, and that, when making that comparison, it took account of all the views of the contested design. Thus, it is apparent from paragraph 25 that the Board of Appeal found that, in the case of the contested design, ‘two shades or colours [were] visible on the clock-face in the 12 o’clock and 6 o’clock positions’ and that ‘four distinct shades [were] visible at all other times’. It also found that ‘the earlier design [was] able to produce a wide spectrum of colours by a movement controlled by the hands, the combination and intensity of which change[d] with time’. The Board of Appeal therefore described, in a summary manner, the different views of the earlier design ‘Farbfolge II, 12 Stunden im 5-Minuten Takt’, which was the only one that enabled the change of the colours and of the intensity of the shades at five-minute intervals to be recognised immediately, and compared it to the contested design.

46 Moreover, the Board of Appeal stated, in paragraph 25 of the contested decision, that ‘no two uniform shades or colours [were] possible in the 12 o’clock and 6 o’clock positions in the earlier designs’, which constituted a significant difference between the designs at issue. The representation of the dial in the 12 o’clock position in the contested design, which displays one half in white and the other in black, both being uniform, is different from that in the first view from the left of the earlier design ‘Farbfolge II, 12 Stunden im 5-Minuten Takt’, represented in colour in paragraph 5 above. [The latter] displays a graded combination of dark colours and of white. Indeed, as the applicant himself concedes, the contested design cannot achieve the 12 o’clock position as it appears in the earlier design ‘Farbfolge II, 12 Stunden im 5-Minuten Takt’. Similarly, contrary to what the applicant claims, the 6 o’clock position in the contested design, which is represented by two uniform tones of grey, is different from the seventh view from the left of the earlier design ‘Farbfolge II, 12 Stunden im 5-Minuten Takt’, which displays a graded combination of red and of green giving rise to, at least, four different shades.

47 It follows from the above that the Board of Appeal did carry out a comparison of the contested design with the earlier design ‘Farbfolge II, 12 Stunden im 5-Minuten Takt’, represented in colour in paragraph 5 above, and that it concluded therefrom that the features of the designs at issue differed significantly.

48 The applicant also claims that, when comparing the designs at issue, the Board of Appeal should have taken account of the fact that the contested design was registered in black and white, and that it should consequently have found that colour is irrelevant as far as concerns novelty.

49 That argument must be rejected as irrelevant. As has been stated by the Court in paragraph 40 above, the Board of Appeal based its assessment as to novelty, as set out in paragraph 27 of the contested decision, on the differences established in the course of its examination of whether the contested design had individual character, as is clear from paragraph 25 of the contested decision. Accordingly, it found that, in the case of the earlier designs, the graded sequence of the discs that compose [those designs] was able to produce a wide spectrum of colours, the combination and intensity of which changed with the time, whereas in the case of the contested design, only two uniform colours were displayed in the 12 o’clock and 6 o’clock positions or four colours in the positions for other times with no variation in intensity. The Board of Appeal’s reasoning is thus based on the ability of the designs at issue to produce a more or less wide spectrum of colours, and a permanent change in tones, and not on the difference in colour between them. Therefore, the Board of Appeal cannot be accused, in the assessment of the differences between the designs at issue, of failing to take account of the fact that the contested design was registered in black and white and [cannot be criticised] for not finding that colour was irrelevant in circumstances such as those of this case.

50 Having regard to all of the foregoing, it must be concluded that the Board of Appeal was correct to find, in paragraph 27 of the contested decision, that the designs at issue could not be deemed to be identical within the meaning of Article 5 of Regulation No 6/2002.

51 This first plea must, therefore, be rejected.

Second plea, alleging infringement of Articles 4 and 6, read in conjunction with Article 25(1)(b), of Regulation No 6/2002

52 First, the applicant submits that the Board of Appeal should have upheld a less strict interpretation of the concept of individual character and should not have equated the identity of the overall impression produced by the designs at issue for the purposes of Article 6 of Regulation No 6/2002, with identity or ‘identi[[ty] except in] immaterial details’ for the purposes of Article 5 of that regulation. Secondly, the applicant submits that [the Board of Appeal] should not have taken account of the differences in colours between the designs at issue for the purpose of assessing the individual character of the contested design.

53 In addition, the applicant claims that the Board of Appeal did not examine, in the contested decision, the overall impression produced on the informed user by the designs at issue, but confined itself to finding that some differences led to a different perception by the informed user.

54 The intervener contends that the degree of freedom of the designer is limited by the technical requirements imposed by the presence of the coloured, moving, overlapping foils which necessarily form part of a dial whose colours change with the movement of the hands. Consequently, even slight differences would suffice to establish the individual character of the contested design.

55 Under Article 6(1)(b) of Regulation No 6/2002, individual character is to be assessed, in the case of a registered Community design, in the light of the overall impression produced on the informed user, which must be different from that produced by any design made available to the public before the date on which the application for registration was filed or, if a priority is claimed, the date of priority. Article 6(2) of Regulation No 6/2002 states that, for the purposes of that assessment, the degree of freedom of the designer in developing the design must be taken into consideration.

56 In that regard, it should be noted that, contrary to what the applicant claims, the Board of Appeal did not equate the identity of the overall impression produced by the designs at issue for the purposes of Article 6 of Regulation No 6/2002, with identity or ‘identi[[ty] except in] immaterial details’ for the purposes of Article 5 of that regulation. The Board of Appeal recorded, in paragraph 25 of the contested decision, the differences between the designs at issue, namely, as regards the earlier designs, the possibility of obtaining a larger combination of colours and a variation in the intensity of those colours; and it found, in paragraph 26 of the contested decision, that, from the point of view of the informed user, those differences were sufficiently important as to produce a different overall impression.

57 According to the case-law, the informed user is a person who is particularly observant and who has some awareness of the previous state of the art, that is to say, the previous designs relating to the product in question that had been disclosed on the date of filing of the contested design (Case T‑9/07 Grupo Promer Mon Graphic v OHIM – PepsiCo (Representation of a Circular Promotional Item) [2010] ECR II‑981, paragraph 62, and judgment of 9 September 2011 in Case T‑11/08 Kwang Yang Motor v OHIM – Honda Giken Kogyo (Internal Combustion Engine), not published in the ECR, paragraph 23).

58 The status of ‘user’ implies that the person concerned uses the product in which the design is incorporated, in accordance with the purpose for which the product is intended (Case T‑153/08 Shenzhen Taiden v OHIM – Bosch Security Systems (Communications Equipment) [2010] ECR II‑2517, paragraph 46, and Internal Combustion Engine, paragraph 24).

59 The qualifier ‘informed’ suggests in addition that, without being a designer or a technical expert, the user knows the various designs which exist in the sector concerned, possesses a certain degree of knowledge with regard to the features which those designs normally include, and, as a result of his interest in the products concerned, shows a relatively high degree of attention when he uses them (Communications Equipment, paragraph 47, and Internal Combustion Engine, paragraph 25).

60 In the present case, it is apparent from paragraph 10 of the contested decision that the Invalidity Division found that the informed user was a person familiar with the design of timepieces. That conclusion was not disputed by the applicant before the Board of Appeal. According to the case-law, the decision of the Invalidity Division, together with its statement of reasons, forms part of the context in which the contested decision was adopted, a context which is known to the applicant and which enables the Court to carry out fully its judicial review as to whether the assessment of individual character of the design at issue was well founded (see, to that effect, judgment of 6 October 2011 in Case T‑246/10 Industrias Francisco Ivars v OHIM – Motive (Mechanical Speed Reducer), not published in the ECR, paragraph 20). Therefore, it is the point of view of the informed user, as defined by the Invalidity Division, that the Board of Appeal used to establish that the differences between the designs at issue were important enough to produce a different overall impression and to recognise, as a consequence, the individual character of the contested design.

61 Contrary to what the applicant claims, the Board of Appeal did not take account of the difference in colour between the designs at issue for the purpose of assessing the individual character of the contested design. As stated in paragraph 49 above, the Board of Appeal based its assessment on the fact that, in the case of the earlier designs, the graded sequence of the discs that compose [those designs] was able to produce a wide spectrum of colours, the combination and intensity of which changed with the time, whereas in the case of the contested design, only two uniform colours were displayed in the 12 o’clock and 6 o’clock positions or four colours in the positions for other hours with no variation in intensity. The Board of Appeal’s reasoning is thus based on the ability of the designs at issue to produce a more or less wide spectrum of colours, and a permanent change in tones, and not on the difference in colour between them.

62 Even if, as the applicant claims, the differences between the designs at issue could be regarded as slight, they will easily be perceived by the informed user. Further, when assessing whether a design has individual character, account should be taken of the nature of the product to which the design is applied or in which it is incorporated, and, in particular, the industrial sector to which it belongs (Communications Equipment, paragraph 43). In the present case, concerning watch dials, parts of watch dials and hands of dials, the view must be taken that they are intended to be worn visibly on the wrist and that the informed user will pay particular attention to their appearance. Indeed, he will examine them closely and will therefore be able to see, as was stated in paragraph 56 above, that the earlier designs produce a larger combination of colours than the contested design and, unlike the latter, a variation in the intensity of the colours. Given the importance of the appearance of those products to the informed user, the differences, even if assumed to be slight, will not be regarded by him as being insignificant.

63 Therefore, it must be concluded that the Board of Appeal was correct to hold that the differences mentioned in paragraph 56 above had a significant impact on the overall impression produced by the designs at issue, so that they produce a different overall impression from the point of view of an informed user.

64 The applicant argues also that watch dial designs can give rise to a practically unlimited number of reproductions or representations and that it was, therefore, open to the designer of the contested design not to reproduce the original idea of the earlier designs, first developed in those designs, that is, to show the time by the change in colours.

65 The Board of Appeal pointed out, in paragraph 22 of the contested decision, that the degree of freedom of the designer was limited only by the need to track and display the changing hours.

66 In response to a question put to it by the Court at the hearing, formal note of which question and response was taken in the minutes of the hearing, the intervener stated that, by its arguments relating to the degree of freedom of the designer, [and] taking account of the fact that, in the intervener’s view, the freedom of the designer was limited by technical reasons, it intended to dispute the assessment made by the Board of Appeal on that point.

67 Inasmuch as the intervener was successful as regards the issue of the existence of a similarity between the designs at issue, disputed in the present proceedings, it has established that it has an interest in applying, under the second subparagraph of Article 134(2) of the Rules of Procedure, for an independent form of order, seeking alteration of the contested decision so far as concerns the degree of freedom of the designer, which [it contends] is highly relevant to the assessment of the individual character of the contested design (see, by analogy, Case T‑405/05 Powerserv Personalservice v OHIM – Manpower (MANPOWER) [2008] ECR II‑2883, paragraph 24). This conclusion cannot be invalidated by the merely formal circumstance that the intervener did not expressly seek the alteration of the contested decision in its submissions (see, by analogy, judgment of 14 September 2011 in Case T‑485/07 Olive Line International v OHIM – Knopf (O-live), not published in the ECR, paragraph 65).

68 However, contrary to what the intervener contends, the degree of freedom of the designer is not limited in the circumstances of the present case. As is apparent from paragraph 3 above, the products in respect of which the contested design was registered correspond to the following description: ‘Watch dials, parts of watch dials, hands of dials’. That description is quite broad, for it does not contain any detail as to the type of watches or the way in which they show the time. Therefore, the intervener cannot contend that, for technical reasons, the freedom of the designer is limited.

69 Accordingly, the finding of the Board of Appeal that the degree of freedom of the designer is limited only by the need to track and display the changing hours must be upheld.

70 As regards the applicant’s argument that the designer of the contested design should not have reproduced the original idea of the earlier designs, that argument must be rejected as unfounded. It is true that the possibilities for the design of a watch dial are practically unlimited and include, inter alia, those in which the colour or colours change. Some models may be more complex in form, such as that of the earlier designs in which the time is represented by the colours or shades of colours generated by the superposition of discs or half-discs of a single colour, enabling the user to tell the time on the basis of the change in those colours or of their shades. The form of the earlier designs is conceived in such a way that the intensity of the colours increases or decreases around the disc.

71 The contested design is an uncomplicated form of a watch dial that changes colour and that, as stated in paragraph 62 above, from the point of view of the informed user, differs from the earlier designs in significant, not inconsiderable features concerning the appearance of the dials. The contested design cannot, therefore, be regarded as a reproduction of the earlier designs or of the original idea that was developed for the first time in them.

72 Moreover, as is apparent from Articles 1 and 3 of Regulation No 6/2002, as a rule, the law relating to designs protects the appearance of the whole or a part of a product, but does not expressly protect the ideas that prevailed at the time of its conception. Therefore, the applicant cannot seek to obtain, on the basis of the earlier designs, a protection for those designs’ underlying idea, that is, the idea of a watch dial that makes it possible to tell the time on the basis of the colours of the discs that compose it.

73 In the light of all the foregoing, the second plea must be rejected.

Third plea, alleging infringement of Article 25(1)(f) of Regulation No 6/2002

74 The applicant submits that the Board of Appeal failed to take into consideration the fact that the earlier designs constituted a work of art protected by German copyright law, the principal idea of which work of art, namely, the representation of time by different colours and shades, has been used without authorisation in the contested design.

75 In addition, he claims that the expert’s report drafted by an expert on the works of Paul Heimbach was not taken into consideration by the Board of Appeal, despite its being relevant for the purpose of determining the extent of the protection conferred by copyright.

76 As a preliminary point, it must be noted that, as the administrative file shows, the expert’s report was submitted outside the prescribed period and it was therefore for the Board of Appeal to decide on its admissibility.

77 It must also be noted that, as stated in paragraph 21 above, it is not for the expert to make a legal assessment of the extent of the protection conferred by copyright and on the existence of an infringement of that right.

78 Therefore, the Board of Appeal was right not to take into account the considerations of a legal nature contained in the expert’s report submitted by the applicant during the administrative procedure.

79 So far as concerns the applicant’s allegation of infringement of copyright of the earlier works of art, under Article 25(1)(f) of Regulation No 6/2002 a Community design may be declared invalid if it constitutes an unauthorised use of a work protected under the copyright law of a Member State. Accordingly, the protection may be invoked by the copyright holder when, in accordance with the law of the Member State conferring the protection on him, he can prevent the use of that design.

80 Notwithstanding the provisions of national law to which he referred in paragraph 39 of the application, the applicant has, however, not provided in the present case any information as to the scope of copyright protection in Germany, in particular as to whether, under German law, copyright protection prohibits the unauthorised reproduction of the idea underlying the earlier works of art, and is not limited to protecting the configuration or features of those works.

81 As the Board of Appeal stated in paragraph 32 of the contested decision, in accordance with the international agreements on copyright to which Germany is a party, copyright protection extends to the configuration or to the features of the work and not to ideas.

82 In the light of the foregoing, the third plea must be rejected and, therefore, the action in its entirety.

Costs

83 Under Article 87(2) of the Rules of Procedure, the unsuccessful party is to be ordered to pay the costs if they have been applied for in the successful party’s pleadings. As the applicant has been unsuccessful, he must be ordered to pay the costs, in accordance with the form of order sought by OHIM and the intervener.

On those grounds,

THE GENERAL COURT (Sixth Chamber)

hereby:

1. Dismisses the action;

2. Orders Mr Erich Kastenholz to pay the costs.

Kanninen | Soldevila Fragoso | Popescu |

Delivered in open court in Luxembourg on 6 June 2013.

[Signatures]