JUDGMENT OF THE GENERAL COURT (Seventh Chamber)

19 April 2013 (*)

(Community trade mark – Invalidity proceedings – Community figurative mark Al bustan – Earlier national figurative mark ALBUSTAN – Genuine use of the earlier mark – Article 57(2) and (3) of Regulation (EC) No 207/2009)

In Case T‑454/11,

Luna International Ltd, established in London (United Kingdom), represented by S. Malynicz, Barrister,

applicant,

v

Office for Harmonisation in the Internal Market (Trade Marks and Designs) (OHIM), represented by J. Crespo Carrillo, acting as Agent,

defendant,

the other party to the proceedings before the Board of Appeal of OHIM being

Asteris Industrial and Commercial Company SA, established in Athens (Greece),

ACTION brought against the decision of the Second Board of Appeal of OHIM of 20 May 2011 (Case R 1358/2008-2), concerning invalidity proceedings between Asteris Industrial and Commercial Company SA and Luna International Ltd,

THE GENERAL COURT (Seventh Chamber),

composed of A. Dittrich, President, I. Wiszniewska-Białecka (Rapporteur) and M. Prek, Judges,

Registrar: T. Weiler, Administrator,

having regard to the application lodged at the Registry of the General Court on 11 August 2011,

having regard to the response lodged at the Court Registry on 13 December 2011,

further to the hearing on 17 January 2013,

gives the following

Judgment

Background to the dispute

1 On 30 August 2005, the applicant, Luna International Ltd, was granted registration under No 003540846 by the Office for Harmonisation in the Internal Market (Trade Marks and Designs) (OHIM) of the following figurative Community trade mark:

2 That registration had been applied for on 13 November 2003.

3 The goods in respect of which the trade mark Al bustan was registered are in Classes 29 to 32 of the Nice Agreement concerning the International Classification of Goods and Services for the Purposes of the Registration of Marks of 15 June 1957, as revised and amended, and correspond, for each of those classes, to the following description:

– Class 29: ‘Meat, fish, poultry and game; meat extracts; preserved, dried and cooked fruits and vegetables; jellies, jams, compotes; eggs, milk and milk products; edible oils and fats; snack foods and prepared meals’;

– Class 30: ‘Coffee, tea, cocoa, sugar, rice, tapioca, sago, artificial coffee; flour and preparations made from cereals, bread, pastry and confectionery, ices; honey, treacle; yeast, baking-powder; salt, mustard; vinegar, sauces (condiments); spices; ice; snack foods and prepared meals’;

– Class 31: ‘Agricultural, horticultural and forestry products and grains not included in other classes; fresh fruits and vegetables; seeds, natural plants and flowers; foodstuffs for animals, malt’;

– Class 32: ‘Mineral and aerated waters and other non-alcoholic drinks; fruit drinks and fruit juices; syrups and other and preparations for making beverages; beers and shandy’.

4 On 27 March 2006, Asteris Industrial and Commercial Company SA (‘Asteris’) filed an application with OHIM for a declaration of invalidity in respect of the mark Al bustan, in accordance with Article 51(1)(b) of Council Regulation (EC) No 40/94 of 20 December 1993 on the Community trade mark (OJ 1994 L 11, p. 1), as amended (now Article 52(1)(b) of Council Regulation (EC) No 207/2009 of 26 February 2009 on the Community trade mark (OJ 2009 L 78, p. 1)), and Article 52(1)(a) of Regulation No 40/94, read in conjunction with Article 8(1)(a) and (b) and Article 8(5) of that regulation (now Article 53(1)(a), Article 8(1)(a) and (b) and Article 8(5) of Regulation No 207/2009, respectively).

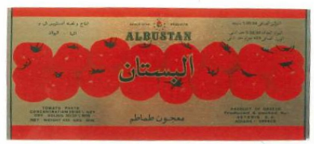

5 The application for a declaration of invalidity was based on the figurative mark, reproduced below, covered by Greek registration No 137497, filed on 24 November 1997 and granted on 19 June 2000, for goods falling within Class 29 corresponding to the following description: ‘Tomato paste of various concentrations and packages, in cans; peeled tomatoes, in cans; various tomato products (tomato juice, concasse, pumarro etc.) in cans; fruit juices, in cans; preserved fruit, in cans’:

6 The reputation of the earlier mark was relied on for part of the goods covered by its registration, namely ‘Tomato paste and tomato products’ in Class 29.

7 The application for a declaration of invalidity was directed against all the goods covered by the Al bustan Community trade mark.

8 On 4 July 2006, on application by the applicant, Asteris was requested by OHIM to furnish proof, in accordance with Article 43(2) and (3) of Regulation No 40/94 (now Article 42(2) and (3) of Regulation No 207/2009), that, during the five‑year period preceding the application for a declaration of invalidity, the earlier mark had been put to genuine use in the Member State in which it is protected.

9 In response, on 6 December 2006, Asteris produced evidence of use of the earlier mark.

10 By decision of 22 July 2008, the Cancellation Division of OHIM granted the application for a declaration of invalidity, on the basis of Article 8(1)(b) of Regulation No 40/94, read in conjunction with Article 52(1)(a) of that regulation, in respect of part of the goods covered by the contested mark Al bustan, namely ‘preserved, dried and cooked fruits and vegetables; jellies, jams, compotes; edible oils and fats’ in Class 29; ‘salt, mustard; vinegars, sauces (condiments); spices’ in Class 30; ‘fresh fruits and vegetables’ in Class 31; and ‘fruit drinks and fruit juices’ in Class 32.

11 On 19 September 2008, the applicant lodged an appeal with OHIM against the decision of the Cancellation Division, disputing the proof of use of the earlier mark and the similarity of the trade marks at issue.

12 On 11 November 2010, OHIM requested Asteris to furnish additional evidence showing the earlier mark as used on the products.

13 On 10 and 13 December 2010, Asteris produced further evidence of use.

14 By decision of 20 May 2011 (‘the contested decision’), the Second Board of Appeal of OHIM dismissed the appeal.

15 As regards proof of genuine use of the earlier mark, the Board of Appeal observed that Asteris had failed to furnish proof that the earlier mark had been used as actually registered. However, it concluded that the form of use of the earlier trade mark did not alter the distinctive character of the mark registered. As regards the time of use, the Board of Appeal concluded that, taking into account the dates appearing on the invoices and other documents showing the earlier mark, together with the undated images of the earlier mark, Asteris had proved that the earlier mark had been used in a form which did not alter its distinctive character during the relevant period. With regard to the place of use, the Board of Appeal noted that the earlier mark had been used in connection with ‘tomato paste’, which had been mainly exported from Greece to Arabic countries, and that, as affixing the earlier mark to the goods or their packaging constitutes use of this mark, the mark had been put to genuine use in the relevant territory. As regards the extent of use, it considered that the evidence of use, containing figures relating to the quantity of goods, showed genuine use of the earlier mark for ‘tomato paste’. The Board of Appeal concluded that genuine use of the earlier mark had been proven for ‘tomato paste of various concentrations and packages, in cans; peeled tomatoes, in cans; various tomato products (tomato juice, concasse, pumarro, etc.) in cans; fruit juices, in cans’, but not for ‘preserved fruits, in cans’, in Class 29.

16 As regards the likelihood of confusion, considering that: (i) the fruits and vegetables in various forms, jellies, jams, compotes and sauces (condiments) covered by the mark at issue and the various tomato products in cans covered by the earlier mark were identical or similar; (ii) the other goods covered by the mark at issue, namely, edible oils and fats, salt, mustard, vinegars, spices, and the goods covered by the earlier mark were similar to a low degree; and (iii) the trade marks at issue were similar to a medium degree, the Board of Appeal concluded that there was a likelihood of confusion within the meaning of Article 8(1)(b) of Regulation No 207/2009 for all the goods in respect of which the Cancellation Division had granted the application for a declaration of invalidity.

Forms of order sought by the parties

17 The applicant claims that the Court should:

– annul the contested decision;

– order OHIM and Asteris Industrial and Commercial Company to pay the costs.

18 OHIM contends that the Court should:

– dismiss the action;

– order the applicant to pay the costs.

Law

19 In support of its action, the applicant relies on a single plea in law, alleging infringement of Article 53(1) and Article 57(2) and (3) of Regulation No 207/2009, and claims that the Board of Appeal wrongly concluded that the evidence submitted by Asteris was sufficient to establish genuine use of the earlier trade mark.

20 It is apparent from recital 10 in the preamble to Regulation No 207/2009 that the legislature considered that there is no justification for protecting an earlier trade mark, except where it is actually used. In keeping with that recital, Article 57(2) and (3) of Regulation No 207/2009 provides that the proprietor of a Community trade mark may request proof that the earlier trade mark has been put to genuine use, in the territory in which it is protected, during the five‑year period preceding the date of the application for a declaration of invalidity. Furthermore, if, at the date on which the Community trade mark application was published, the earlier trade mark had been registered for not less than five years, the proprietor of the earlier trade mark is to furnish proof that the earlier trade mark was put to genuine use in that territory during the five‑year period preceding that publication.

21 Moreover, the second subparagraph of Article 15(1) of Regulation No 207/2009 provides that the following constitute use of the Community trade mark:

‘(a) use of the Community trade mark in a form differing in elements which do not alter the distinctive character of the mark in the form in which it was registered;

(b) affixing of the Community trade mark to goods or to the packaging thereof in the Community solely for export purposes.’

22 The purpose of Article 15(1)(a) of Regulation No 207/2009, which avoids imposing strict conformity between the form of the trade mark as used and the form in which the mark was registered, is to allow its proprietor in the commercial exploitation of the sign to make variations which, without altering its distinctive character, enable it to be better adapted to the marketing and promotion requirements of the goods or services concerned. In accordance with its purpose, the material scope of that provision must be regarded as limited to situations in which the sign actually used by the proprietor of a trade mark to identify the goods or services in respect of which the mark was registered constitutes the form in which that same mark is commercially exploited. In such situations, where the sign used in trade differs from the form in which it was registered only in negligible elements, so that the two signs may be regarded as broadly equivalent, the provision in question provides that the obligation to use the registered trade mark may be fulfilled by furnishing proof of use of the sign which constitutes the form in which it is used in trade (judgments of 10 June 2010 in Case T‑482/08 Atlas Transport v OHIM – Hartmann (ATLAS TRANSPORT), not published in the ECR, paragraph 30, and 24 May 2012 in Case T‑152/11 TMS Trademark-Schutzrechtsverwertungsgesellschaft v OHIM – Comercial Jacinto Parera (MAD), not published in the ECR, paragraph 16).

23 According to established case-law on Article 57(2) and (3) of Regulation No 207/2009, the purpose of the requirement to show genuine use of the earlier trade mark is to limit the likelihood of conflict between two marks by protecting only marks that have actually been used, in so far as there is no good commercial justification for their not being used (judgments of 23 September 2009 in Joined Cases T‑493/07, T‑26/08 and T‑27/08 GlaxoSmithkline and Others v OHIM – Serono Genetics Institute (FAMOXIN), not published in the ECR, paragraph 32, and 29 February 2012 in Joined Cases T‑77/10 and T‑78/10 Certmedica International and Lehning entreprise v OHIM – Lehning entreprise and Certmedica International (L112), not published in the ECR, paragraph 39). However, the purpose of the provision is not to assess commercial success or to review the economic strategy of an undertaking, nor is it intended to restrict trade‑mark protection to the case where large-scale commercial use has been made of the marks (judgments of 10 September 2008 in Case T‑325/06 Boston Scientific v OHIM – Terumo (CAPIO), not published in the ECR, paragraph 28, and 23 September 2009 in Case T‑409/07 Cohausz v OHIM – Izquierdo Faces (acopat), not published in the ECR, paragraph 28).

24 Rule 22(3) of Commission Regulation (EC) No 2868/95 of 13 December 1995 implementing Regulation No 40/94 (OJ 1995 L 303, p. 1), as amended, applicable mutatis mutandis in invalidity proceedings pursuant to Rule 40(6) of that regulation, provides that proof of use must relate to the place, time, nature and extent of use of the opposing trade mark (acopat, paragraph 23 above, paragraph 27).

25 Rule 22(4) of Regulation No 2868/95, applicable mutatis mutandis to invalidity proceedings pursuant to Rule 40(6) of that regulation, provides that evidence of genuine use is, in principle, to be confined to the submission of supporting documents and items such as packages, labels, price lists, catalogues, invoices, photographs, newspaper advertisements and sworn or affirmed statements in writing, as referred to in Article 78(1)(f) of Regulation No 207/2009 (L112, paragraph 23 above, paragraph 41).

26 As is apparent from Case C‑40/01 Ansul [2003] ECR I‑2439, paragraph 43, there is genuine use of a trade mark where the mark is used in accordance with its essential function, which is to guarantee the identity of the origin of the goods or services for which it is registered, in order to create or preserve an outlet for those goods or services; genuine use does not include token use for the sole purpose of preserving the rights conferred by the mark. Moreover, the condition of genuine use of the mark requires that the mark, as protected on the relevant territory, be used publicly and externally (see CAPIO, paragraph 23 above, paragraph 29 and the case‑law cited, and MAD, paragraph 22 above, paragraph 19).

27 In the assessment of whether use of the trade mark is genuine, regard must be had to all the facts and circumstances relevant to establishing whether the commercial exploitation of the mark is real, particularly whether such use is viewed as warranted in the economic sector concerned in order to maintain or create a share in the market for the goods or services protected by the mark, the nature of those goods or services, the characteristics of the market and the scale and frequency of use of the mark (see CAPIO, paragraph 23 above, paragraph 30 and the case-law cited; acopat, paragraph 23 above, paragraph 31; and MAD, paragraph 22 above, paragraph 20).

28 As to the extent of the use to which the earlier trade mark has been put, account must be taken, in particular, of the commercial volume of the overall use, as well as the length of the period during which the mark was used and the frequency of use (see CAPIO, paragraph 23 above, paragraph 31 and the case‑law cited; acopat, paragraph 23 above, paragraph 32; and MAD, paragraph 22 above, paragraph 21).

29 The General Court has made it clear that genuine use of a trade mark cannot be proved by means of probabilities or suppositions, but must be demonstrated by solid and objective evidence of effective and sufficient use of the trade mark on the market concerned (see CAPIO, paragraph 23 above, paragraph 34 and the case‑law cited; acopat, paragraph 23 above, paragraph 36; and MAD, paragraph 22 above, paragraph 24).

30 It should be noted that, in the course of the administrative procedure, Asteris produced, inter alia, the following items of evidence for the purpose of demonstrating genuine use of the earlier mark:

– on 27 March 2006, annexed to the application for a declaration of invalidity, administrative documents in the form of inspection certificates relating to the export of pallets of cans of AL BUSTAN tomato paste to Libya and Sudan between 2001 and 2005;

– on 6 December 2006, in response to the request for proof of genuine use of the earlier mark:

– a reproduction of a label representing the earlier mark (document 1);

– certificates from the Libyan General Directorate for Commercial Affairs and the Arab‑Hellenic Chamber of Commerce indicating that Asteris exported tomato products to Libya under the trade mark ALBUSTAN (or AL BUSTAN) during the period 1984 – 2002 (documents 2 and 3);

– business requests from various companies, a Greek export company and a number of companies in Africa and the Middle East concerning the marketing of cans of tomato paste under the trade mark ALBUSTAN (or AL BUSTAN), covering the period from June 2003 to June 2005 (documents 4 to 18);

– administrative documents (certificates of origin, bills of lading, cargo manifests, sales invoices) relating to the export of tomato paste under the trade mark ALBUSTAN (or AL BUSTAN) from Greece to Libya and Sudan during the period 2002 to 2005 (documents 19 to 32);

– on 10 December 2010, in response to the request of the Board of Appeal, invoices relating to the sale of tomato paste under the trade mark ALBUSTAN to Libyan companies, dated 12 July 2004, 30 May 2005 and 20 October 2005 (documents 3 to 5 and 7);

– on 13 December 2010, four photographs of cans of tomato paste bearing the lithographic print of the trade mark ALBUSTAN.

31 First, it should be noted that the Board of Appeal considered that the photographs of cans of tomato paste and the reproduction of a label submitted by Asteris reproduce the main elements of the earlier mark as registered, with the exception of the precise number of tomatoes depicted. The Board of Appeal noted that, in the representation of the mark used, all the relevant elements, both verbal and figurative, of the registered trade mark are used in the same proportion and the fact that the images differ in the number of tomatoes is not important, as the tomatoes depicted are of a similar size and colour and arranged over two lines. It concluded from this that the sign used in trade by Asteris differs from the form in which it was registered only in negligible elements, so that the two signs may be regarded as broadly equivalent, and that those elements do not alter the distinctive character of the mark as registered.

32 The applicant accepts that, if Asteris could demonstrate use, those photographs depict markings which would constitute use of a mark in a form differing in elements which do not alter the distinctive character of the mark as registered, in accordance with Article 15(1) of Regulation No 207/2009.

33 With regard to proof of use during the relevant period, the Board of Appeal accepted that it was not possible to retrieve actual dates from the photographs of cans of tomato paste or the reproduction of package labelling submitted by Asteris. It pointed out that the invoices produced by Asteris state that all the details, including the name and kind of product, country of origin, the name and address of the manufacturer, the brand name, the gross and net weight in grams and the production and expiry dates, were lithograph‑printed on the cans of tomato paste in Arabic and English. It considered that, although the brand name was AL BUSTAN and the invoices did not refer to the figurative element of the mark, all those indications on the invoices were also present on the reproduction of the package labelling and on the photographs of the cans. The Board of Appeal concluded that Asteris had proven that the earlier mark had been used during the relevant period, in view of both the dates on the invoices and other documents indicating the mark AL BUSTAN and the undated images of the figurative mark, taken together.

34 The applicant disputes that finding. It submits that the evidence furnished by Asteris was insufficient for the purpose of demonstrating genuine use of the earlier mark during the relevant period. It maintains that the Board of Appeal based its finding on probabilities and suppositions, given that, first, the documents produced by Asteris relating to the relevant period made no reference to the earlier figurative mark and, second, the photographs of cans of tomato paste and the representation of a label are undated.

35 It should be recalled that, although Rule 22 of Regulation No 2868/95 refers to indications concerning the place, time, extent and nature of use, and gives examples of acceptable evidence, such as packages, labels, price lists, catalogues, invoices, photographs, newspaper advertisements and statements in writing, that rule does not state that each item of evidence must necessarily give information about all four elements to which proof of genuine use must relate, namely the place, time, nature and extent of use (Case T‑308/06 Buffalo Milke Automotive Polishing Products v OHIM – Werner & Mertz (BUFFALO MILKE Automotive Polishing Products) [2011] ECR II‑0000, paragraph 61, and MAD, paragraph 22 above, paragraph 33).

36 Moreover, it is established case‑law that it cannot be ruled out that an accumulation of items of evidence may allow the necessary facts to be established, even though each of those items of evidence, taken individually, would be insufficient to constitute proof of the accuracy of those facts (judgment of 17 April 2008 in Case C‑108/07 P Ferrero Deutschland v OHIM, not published in the ECR, paragraph 36, and MAD, paragraph 22 above, paragraph 34).

37 Proof of genuine use of the earlier mark must therefore be established by taking account of all the evidence submitted to the Board of Appeal for assessment.

38 First, the photographs submitted by Asteris represent cans containing tomato paste bearing the brand name ALBUSTAN written in Roman and Arabic characters.

39 The applicant disputes the evidential value of those photographs, since they do not refer to the date on which they were taken and, the applicant submits, it is likely that they were taken in December 2010.

40 It must be recalled that, in order to assess the evidential value of a document, regard should be had, first, to the credibility of the account it contains. Account must then be taken of the person from whom the document originates, the circumstances in which it came into being, the person to whom it was addressed and whether, on its face, the document appears sound and reliable (see the judgment of 13 June 2012 in Case T‑312/11 Süd-Chemie v OHIM – Byk-Cera (CERATIX), not published in the ECR, paragraph 29 and the case‑law cited).

41 It is true, as the Board of Appeal acknowledged, that the photographs submitted by Asteris are undated. Nevertheless, contrary to the submissions of the applicant, that fact alone cannot deprive them of all evidential value.

42 As regards the circumstances in which the photographs were submitted as proof of use, it should be noted that, as a result of OHIM’s request to identify the evidence already submitted or furnish new evidence relating to the mark as used on the goods during the relevant period, Asteris’s legal representative produced those photographs, stating that they represented ‘the way in which the trade mark is and has been used on the products’.

43 The applicant has failed to put forward any argument which could cast doubt on the claim that those photographs represent the earlier mark as used on the products during the relevant period.

44 Moreover, the applicant cannot claim that the statement made by Asteris’s legal representative is valueless and that only Asteris was entitled to make such a statement, since it alone was in a position to have knowledge of the images on the cans of tomato paste during the relevant period. It is sufficient to note that Asteris’s legal representative acted for it in the proceedings before OHIM and took its instructions from that company.

45 In any event, according to case‑law, it is not precluded, in assessing the genuineness of use during the relevant period, that account be taken, where appropriate, of any circumstances subsequent to that period. Such circumstances may make it possible to confirm or better assess the extent to which the trade mark was used during the relevant period (see, to that effect, Case C‑259/02 La Mer Technology [2004] ECR I‑1159, paragraph 31, and Case C‑192/03 P Alcon v OHIM [2004] ECR I‑8993, paragraph 41; see also CAPIO, paragraph 23 above, paragraph 38).

46 Consequently, even if the photographs were taken at a date subsequent to the expiry of the relevant period, it is not precluded that they may be taken into account in order to assess the genuine use of the earlier mark during the relevant period.

47 Second, with regard to the reproduction of a label submitted by Asteris in December 2006, the applicant submits that the Board of Appeal erred in finding that this was ‘an image of the mark as actually used on the product packaging’. The applicant contends that Asteris made no such claim and that the reproduction of the label was undated.

48 That reproduction of a label was submitted by Asteris as a representation of the earlier mark. The applicant does not dispute the Board of Appeal’s conclusion that, since the difference between the mark as registered and the representation in question lay in the number of tomatoes depicted, which is not a distinctive element, the trade mark was used in a form that did not alter its distinctive character. The argument that the reproduction of the label is undated is irrelevant, in accordance with the case-law cited at paragraph 45 above.

49 Furthermore, it should be noted, as observed by the Board of Appeal, that the reproduction of that label matches one of the photographs of a can of tomato paste submitted by Asteris. The applicant has therefore failed to show that the Board of Appeal erred in taking the view that that reproduction of a label corresponds to ‘an image of the mark as actually used on the product packaging’.

50 The Board of Appeal was therefore entitled to take account of that reproduction of a label in assessing whether the earlier mark had been put to genuine use.

51 Third, the certificates and administrative documents submitted by Asteris on 6 December 2006 and the invoices submitted on 10 December 2010 pertaining to the sale of tomato paste under the mark ALBUSTAN (or AL BUSTAN) bear dates corresponding to the relevant period.

52 The applicant disputes the evidential value of those documents. It considers that, although they in fact relate to the relevant period, they do not demonstrate the use of any figurative mark. Those documents simply refer to the ALBUSTAN (or AL BUSTAN) brand, without specifying or confirming that the goods bore the earlier figurative mark or a permissible variant of that mark. The Board of Appeal simply assumed that the details in the photographs matched those listed on the invoices.

53 The General Court has already held that it is incorrect to take the view that invoices are irrelevant on the ground that they do not include the figurative mark alongside the name of each product. The purpose of invoices is to itemise the products sold, so that the number or name of the item concerned must appear on the invoice, possibly together with the name of the registered mark (MAD, paragraph 22 above, paragraph 59).

54 Moreover, the General Court has also held that the fact that the earlier mark is not mentioned on invoices does not constitute evidence to the effect that they are irrelevant for the purpose of demonstrating genuine use of that mark (judgment of 27 September 2007 in Case T‑418/03 La Mer Technology v OHIM – Laboratoires Goëmar (LA MER), not published in the ECR, paragraph 65, and MAD, paragraph 22 above, paragraph 60). In the present case, not only the invoices but also the certificates of origin and the shipment records submitted by Asteris refer to cans of tomato paste bearing the mark ALBUSTAN (or AL BUSTAN) produced in Greece.

55 As observed by the Board of Appeal, the invoices submitted by Asteris contain, in addition to references to the ALBUSTAN trade mark, other details which enable the products to be identified in their packaging. Those invoices refer to the sale of lithograph-printed cans of tomato paste with various details in Arabic and English, as set out at paragraph 33 above, sometimes specifying that they are in two colours. Those details are the same as those that appear on the photographs of cans of tomato paste and on the reproduction of the label submitted by Asteris.

56 Moreover, the applicant claims that Asteris submitted a considerable amount of third party material, none of which confirmed that the product was sold in packaging bearing the earlier mark during the relevant period. The applicant is of the view that Asteris could have asked the third parties concerned to indicate whether the earlier mark was used on the products in question.

57 It should be recalled that, according to the case‑law cited at paragraph 40 above, in order to assess the evidential value of a document, account must be taken, inter alia, of the person from whom the document originates and the circumstances in which it came into being. In the present case, the third parties concerned were not asked to provide the documents in question specifically with a view to their being produced in the invalidity proceedings to prove genuine use of the earlier mark. Asteris chose to submit only documents dating from the relevant period. Since those documents have a commercial or administrative purpose, they cannot be expected to reproduce the figurative mark.

58 Furthermore, since Asteris took the view that those documents were sufficient for the purpose of demonstrating genuine use of the earlier mark, the applicant cannot criticise it for not requesting third parties to make statements to the effect that the product bore the figurative mark during the relevant period, for the purpose of proof of use.

59 It is apparent from the foregoing that the Board of Appeal was entitled to take the view that the mark described on the third party documents, in particular on the invoices dating from the relevant period, corresponded to that on the photographs. Accordingly, the invoices produced by Asteris reflected the sale of products (tomato paste) sold in cans represented on the photographs submitted by Asteris, that is, the sale of products covered by the earlier mark.

60 Contrary to the applicant’s claims, the Board of Appeal did not base its findings on mere probabilities or suppositions, but cross‑checked the various items of evidence submitted by Asteris and deduced from that accumulation of items of evidence that there had been genuine use of the earlier mark during the relevant period.

61 In the light of the case-law cited at paragraphs 35 and 36 above, the Board of Appeal was entitled to take the view that the combination of the photographs and other items of evidence, taken as a whole, constituted evidence of genuine use of the earlier mark during the relevant period.

62 Lastly, the case‑law of the General Court relied on by the applicant in support of its argument that the Board of Appeal cannot rely on suppositions is irrelevant in the present case.

63 Thus, in the case which gave rise to the judgment in Case T‑303/03 Lidl Stiftung v OHIM – REWE-Zentral (Salvita) [2005] ECR II‑1917, the Court found that, apart from a written statement of the applicant’s director of international purchasing, the applicant had failed to furnish any other evidence to corroborate the time and the extent of use of the earlier mark. The only additional evidence comprised copies of the specimen packages of the products concerned, which did not bear any date.

64 In the case which gave rise to the judgment in Case T‑356/02 Vitakraft-Werke Wührmann v OHIM – Krafft (VITAKRAFT) [2004] ECR II‑3445, the only evidence of use submitted by the opponent were catalogues, which were insufficient for the purpose of demonstrating genuine use of the earlier mark, in particular the extent of use. Similarly, in the case which gave rise to the judgment of 30 April 2008 in Case T‑131/06 Rykiel création et diffusion de modèles v OHIM – Cuadrado (SONIA SONIA RYKIEL), not published in the ECR, the Court considered that the evidence produced by the opponent, namely packaging and labels, together with invoices relating to a very small number of goods sold, was insufficient for the purpose of demonstrating the extent of use of the earlier mark.

65 Lastly, in the case which gave rise to the judgment of 18 January 2011 in Case T‑382/08 Advance Magazine Publishers v OHIM – Capela & Irmãos (VOGUE), not published in the ECR, the Court took the view that none of the evidence corroborated the place, time or extent of use. In particular, it stated, with regard to extent of use, that none of the evidence produced by the opponent before OHIM indicated the volume of shoe sales or the turnover from those sales and that the invoices produced related to the sale of shoes to the opponent, not the sale to end consumers of shoes bearing the earlier mark.

66 In those judgments, the Court concluded that the evidence submitted was insufficient for the purpose of establishing the extent of use of the earlier mark. Thus, in line with the case-law cited at paragraph 29 above, the Court found that, in the absence of sound evidence demonstrating actual and sufficient use of the mark on the market concerned, the Board of Appeal had based its findings on mere suppositions.

67 That is not the case here. Asteris provided a number of third party documents, such as certificates of origin or shipment records, as well as invoices, on the basis of which it was possible to establish the sale of a significant quantity of cans of tomato paste bearing the ALBUSTAN trade mark. The evidence produced in the present case was therefore sufficient to establish the extent of use of the earlier mark.

68 It is apparent from all the foregoing considerations that the applicant has failed to establish that the Board of Appeal erred in taking the view that the evidence submitted by Asteris was sufficient for the purpose of demonstrating genuine use of the earlier mark.

69 The single plea in law, alleging infringement of Article 53(1) and Article 57(2) and (3) of Regulation No 207/2009, must therefore be rejected, as must the action in its entirety.

Costs

70 Under Article 87(2) of the Rules of Procedure of the General Court, the unsuccessful party is to be ordered to pay the costs if they have been applied for in the successful party’s pleadings. Since the applicant has been unsuccessful, it must be ordered to pay the costs, in accordance with form of order sought by OHIM.

On those grounds,

THE GENERAL COURT (Seventh Chamber)

hereby:

1. Dismisses the action;

2. Orders Luna International Ltd to pay the costs.

Dittrich | Wiszniewska-Białecka | Prek |

Delivered in open court in Luxembourg on 19 April 2013.

[Signatures]