JUDGMENT OF THE GENERAL COURT (Seventh Chamber)

25 April 2013 (*)

(Community design – Invalidity proceedings – Registered Community design representing a cleaning device – Community three-dimensional mark representing a cleaning device fitted with a spraying device and a sponge – Declaration of invalidity)

In Case T‑55/12,

Su-Shan Chen, established in Sanchong (Taiwan), represented by C. Onken, lawyer,

applicant,

v

Office for Harmonisation in the Internal Market (Trade Marks and Designs) (OHIM), represented by A. Folliard-Monguiral, acting as Agent,

defendant,

the other party to the proceedings before the Board of Appeal of OHIM, intervener before the General Court, being

AM Denmark A/S, established in Kokkedal (Denmark), represented by C. Type Jardorf, lawyer,

ACTION brought against the decision of the Third Board of Appeal of OHIM of 26 October 2011 (Case R 2179/2010-3), relating to invalidity proceedings between AM Denmark A/S and Su-Shan Chen,

THE GENERAL COURT (Seventh Chamber),

composed of A. Dittrich, President, I. Wiszniewska-Białecka and M. Prek (Rapporteur), Judges,

Registrar: E. Coulon,

having regard to the application lodged at the Court Registry on 8 February 2012,

having regard to the response of OHIM lodged at the Court Registry on 16 May 2012,

having regard to the response of the intervener lodged at the Court Registry on 27 April 2012,

having regard to the fact that no application for a hearing was submitted by the parties within the period of one month from notification of closure of the written procedure, and having therefore decided, acting upon a report of the Judge‑Rapporteur, to give a ruling without an oral procedure, pursuant to Article 135a of the Rules of Procedure of the General Court,

gives the following

Judgment

Background to the dispute

1 The applicant, Su-Shan Chen, is the proprietor of the Community design filed on 24 October 2008 and registered at the Office for Harmonisation in the Internal Market (Trade Marks and Designs) (OHIM) under number 1027718-0001.

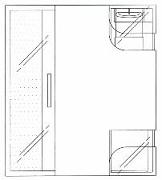

2 The contested design, which is intended to be incorporated into cleaning devices, is represented as follows:

3 The contested design was published in Community Design Bulletin No 236/2008 of 11 November 2008.

4 On 6 October 2009, the intervener, AM Denmark A/S, filed at OHIM an application for a declaration of invalidity of the contested design, pursuant to Articles 4 to 9 and Article 25(1)(e) of Council Regulation (EC) No 6/2002 of 12 December 2001 on Community designs (OJ 2002 L 3, p. 1). In the application for a declaration of invalidity, the intervener claimed that a distinctive sign within the meaning of Article 25(1)(e) of that regulation was used in the contested design.

5 In support of its application for a declaration of invalidity, the intervener relied on the Community three-dimensional mark registered under number 5185079 on 13 February 2008, which is shown below:

6 The earlier mark was registered for goods in Classes 3 and 21 of the Nice Agreement concerning the International Classification of Goods and Services for the Purposes of the Registration of Marks of 15 June 1957, as revised and amended, and corresponds, for each of those classes, to the following description:

– Class 3: ‘Cleaning agents (not for use in manufacturing or for medical purposes), including for office machines, for audio and video apparatus and for computers; cleaning fluids (not for use in manufacturing or for medical purposes), including cleaning fluids for office machines, CD players, pick-up needles, video players, cassette recorders, sound heads for tape recorders; cleaning fluids for computer screens, glass filters for computer screens, keyboards, mice, printers and copying apparatus, disc drives, DVDs, CDs, CD-ROMs; tissues impregnated with preparations for cleaning office machines, for DVDs, CDs; polishing preparations for plastic surfaces on computers, printers and scanners; impregnated cloths (disposable)’;

– Class 21: ‘Equipment and containers for cleaning, including sponges, brushes, wipes, dusting cloths, mops’.

7 By decision of 17 September 2010, the Invalidity Division upheld the application for a declaration of invalidity on the basis of Article 25(1)(e) of Regulation No 6/2002. First, it found that the contested design included the three-dimensional shape of a cleaning device which could be perceived as being a sign. Next, it found that that sign and the earlier mark were similar. Finally, it held that, due to the similarity of the signs at issue and the identity of the goods, there was a likelihood of confusion on the part of the relevant public.

8 On 8 November 2010, the applicant filed a notice of appeal with OHIM, pursuant to Articles 55 to 60 of Regulation No 6/2002, against the Invalidity Division’s decision.

9 By decision of 26 October 2011 (‘the contested decision’), the Third Board of Appeal confirmed that the contested design had to be declared invalid on the basis of Article 25(1)(e) of Regulation No 6/2002.

10 In the first place, it noted that the geometric form, dimensions and shape of the earlier trade mark and of the contested design were highly similar and almost identical in part, and that the slight changes contained in the contested design were of secondary importance. Accordingly, it found that the contested design included the earlier three-dimensional sign and that use was thus made of the earlier trade mark in the contested design in accordance with Article 25(1)(e) of Regulation No 6/2002.

11 In the second place, it analysed the likelihood of confusion. First, after noting that the goods covered by the earlier mark were directed at the general public and that the relevant territory for the purpose of analysing the likelihood of confusion was the European Union as a whole, it stated that the goods in which the contested design was intended to be incorporated were included in the list of goods covered by the earlier trade mark and that they were therefore identical.

12 Next, it considered that the earlier mark and the contested design could only be compared visually and not phonetically or conceptually. It found that neither of the signs contained a word element, that they did not lend themselves to brief, simple descriptions in words, and that they did not evoke any particular concept.

13 It also found that the earlier mark and the contested design were visually similar, stating that the public paid less attention to the slight additions and changes to the contested design and more attention to its overall shape.

14 In addition, while pointing out that the relevant public might not consider the shape of the cleaning device as an indication of its origin, it nevertheless noted that, having regard to the fact that the earlier mark had been registered and had not been declared invalid for lack of distinctive character, it had to be presumed that it had a minimum degree of distinctive character necessary for its registration.

15 Lastly, it concluded that, having regard to the similarity of the contested design to the earlier mark and the identity of the goods, there was a likelihood of confusion, and the low degree of distinctive character of the earlier mark was not sufficient to exclude that likelihood.

Forms of order sought

16 The applicant claims that the Court should:

– annul the contested decision;

– order OHIM and the intervener to pay the costs.

17 OHIM contends that the Court should:

– dismiss the action;

– order the applicant to pay the costs.

18 The intervener contends that the Court should:

– affirm the contested decision in its entirety;

– order the applicant to pay the costs.

Law

19 The applicant relies on two pleas in law. The first alleges breach of Article 25(1)(e) of Regulation No 6/2002 and misinterpretation of the concept of ‘use’. The second plea in law alleges breach of Article 9(1)(b) of Council Regulation (EC) No 207/2009 of 26 February 2009 on the Community trade mark (OJ 2009 L 78, p. 1).

First plea in law: breach of Article 25(1)(e) of Regulation No 6/2002 and misinterpretation of the concept of ‘use’

20 The applicant asserts that the earlier mark is not used in the contested design. First, she considers that certain elements of the earlier mark are absent from the contested design and other elements are added to it. Next, she observes that the earlier mark and the contested design have totally different proportions and that the differences in the geometric form and dimensions of the mark and of the contested design produce a very different overall impression. Finally, she maintains that OHIM was not obliged to presume that the earlier mark had at least the minimum degree of distinctive character necessary for its registration.

21 OHIM and the intervener dispute those arguments.

22 It should be noted that Article 25(1)(e) of Regulation No 6/2002 provides that a design may be declared invalid if a distinctive sign is used in a subsequent design, and Community law or the law of the Member State governing that sign confers on the right holder of the sign the right to prohibit such use.

23 It should also be noted that, as is apparent from the case-law, the ground for invalidity specified in Article 25(1)(e) of Regulation No 6/2002 does not necessarily presuppose a full and detailed reproduction of an earlier distinctive sign in a subsequent Community design. Even if the contested Community design lacks certain features of the sign in question or has different, additional features, there may be ‘use’ of that sign, particularly where the omitted or added features are of secondary importance (Case T‑148/08 Beifa Group v OHIM – Schwan‑Stabilo Schwanhäußer (Instrument for writing) [2010] ECR II‑1681, paragraph 50).

24 That is especially true given the fact, consistently pointed out by the Court, that the public retains only an imperfect memory of the marks registered in the Member States or of Community marks (see, to that effect, Case C‑342/97 Lloyd Schuhfabrik Meyer [1999] ECR I‑3819, paragraph 26, and Case T‑162/01 Laboratorios RTB v OHIM – Giorgio Beverly Hills (GIORGIO BEVERLY HILLS) [2003] ECR II‑2821, paragraph 33). The case-law states that that is the case with every type of distinctive sign. As a consequence, if a distinctive sign as used in a subsequent Community design lacks certain secondary features or has additional such features, the relevant public will not necessarily notice those changes vis‑à‑vis the earlier distinctive sign. On the contrary, the relevant public may believe that the sign it remembers is being used in the subsequent Community design (Instrument for writing, cited in paragraph 23 above, paragraph 51).

25 In the present case, it should be stated, as is apparent from paragraphs 16 and 17 of the contested decision, that the earlier mark and the contested design both consist of a cleaning device in the shape of a compact rectangular body rounded at the edges which houses a spray device on one side and a cylindrical sponge on the other.

26 The Board of Appeal’s assessment at paragraph 18 of the contested decision that the geometric form and dimensions of the earlier mark and of the contested design are highly similar and identical in part must be approved.

27 Admittedly, it must be accepted that the contested design has certain differences and additions as against the earlier mark. However, they are limited to a transparent cap, a transparent bottom part on both sides of the main body, and a thin plastic cover placed around the sponge. OHIM rightly notes that, in view of their secondary importance, those additions and differences cannot dominate the impression left by the contested design. The considerations formulated by OHIM that, first, the cap and the cover are removable and therefore accessories in respect of the main body of the cleaning device and, second, the transparency of the bottom part of the body in the contested design in no way amends its outer appearance must be approved.

28 Consequently, the Board of Appeal was correct in finding, at paragraph 18 of the contested decision, that the abovementioned additions and differences did not prevent the features of the earlier mark, namely those of a cleaning device in the shape of a compact rectangular body rounded at the edges and housing a spray device on one side and a cylindrical sponge on the other, from being discernible in the contested design.

29 The Board of Appeal therefore did not breach Article 25(1)(e) of Regulation No 6/2002 by considering that the earlier mark was used in the contested design.

30 None of the arguments advanced by the applicant is sufficient to challenge those findings.

31 First, contrary to what the applicant claims in essence and as is apparent from the case-law recalled at paragraph 23 above, the ground for invalidity specified in Article 25(1)(e) of Regulation No 6/2002 does not presuppose a full and detailed reproduction of the earlier distinctive sign in the design concerned.

32 Second, the applicant relies to no avail on the fact that, since the shape of the contested design is almost square and the height of the earlier mark is one and a half times its width, the earlier mark and the contested design have completely different proportions.

33 As the applicant herself admits, the contested design is a rectangle, not a square. Moreover, the applicant is wrong to consider that the proportions are ‘completely different’. In the light of the case-law referred to at paragraph 24 above, according to which the public retains only an imperfect memory of the sign, the consumer will not perceive the slightly more elongated feature of the earlier mark if the shapes are presented to it at different times.

34 Third, the applicant’s argument that OHIM did not have to presume that the earlier trade mark possessed at least a minimum degree of distinctive character necessary for its registration is irrelevant. The validity of the earlier mark cannot be called in question in invalidity proceedings regarding a Community design. As OHIM stated, if the applicant was of the opinion that the earlier Community mark was devoid of any distinctive character and had been registered in breach of Article 7(1)(b) of Council Regulation (EC) No 40/94 of 20 December 1993 on the Community trade mark (OJ 1994, L 11, p. 1), as amended (now Article 7(1)(b) of Regulation No 207/2009), it was a matter for the applicant to file an application for annulment, which she did not.

35 It follows from the foregoing that the first plea in law, alleging breach of Article 25(1)(e) of Regulation No 6/2002 and misinterpretation of the concept of ‘use’ of a distinctive sign, must be rejected.

Second plea in law: breach of Article 9(1)(b) of Regulation No 207/2009

36 In support of her second plea in law, alleging breach of Article 9(1)(b) of Regulation No 207/2009, the applicant raises two claims, alleging that the contested design will not be perceived as an indication of the origin of the goods and that the earlier mark and the contested design are not similar and therefore there is no likelihood of confusion.

37 At the outset, it should be noted that, under Article 9(1)(b) of Regulation No 207/2009, the proprietor of a Community trade mark is entitled to prevent all third parties not having his consent from using in the course of trade any sign where, because of its identity with, or similarity to, the Community trade mark and the identity or similarity of the goods or services covered by the Community trade mark and the sign, there exists a likelihood of confusion on the part of the public. That provision specifies that the likelihood of confusion includes the likelihood of association between the sign and the trade mark.

38 In the first claim, the applicant asserts that, even if the earlier trade mark were assumed to be used in the contested design, that design consists only of the shape of a cleaning device and will not therefore be perceived as an indication of the origin of the goods. She observes that the use of the cleaning device does not in itself constitute use as a trade mark and submits that the use of the contested design cannot therefore be prohibited under Article 9(1)(b) of Regulation No 207/2009.

39 It is clear from the scheme of Article 9(1)(b) of Regulation No 207/2009 that the use of a sign in relation to goods or services is use for the purpose of distinguishing the goods or services in question (see, by analogy, Case C‑17/06 Céline [2007] ECR I‑7041, paragraph 20).

40 To show that the contested design cannot be perceived, in the present case, as an indication of the origin of the goods, the applicant merely relies on the case-law according to which average consumers are not in the habit of making assumptions about the origin of goods on the basis of their shape or the shape of their packaging in the absence of any graphic or word element (Joined Cases C‑456/01 P and C‑457/01 P Henkel v OHIM [2004] ECR I‑5089). First, that case‑law does not preclude the view that the reproduction of the shape of goods may be perceived as an indication of their origin. Second, the shape of the design which incorporates the cleaning device appears to be sufficiently unusual compared to the norms of the sector and sufficiently striking that, when that design is used, the relevant consumer will be led to perceive it as an indication of the origin of the cleaning products.

41 In this respect, it must be stated that the applicant has not put forward any evidence to show that the sign is usual in terms of the norms of the sector and that the public will not see it as an indication of the origin of the cleaning devices.

42 Consequently, it must be held that the use of the contested design for cleaning devices may be use for the purpose of distinguishing those cleaning products. In that context, OHIM may apply Article 9(1)(b) of Regulation No 207/2009 in conjunction with Article 25(1)(e) of Regulation No 6/2002.

43 In the second claim, the applicant submits that there is no likelihood of confusion on the part of the public concerned, on the ground that the earlier mark and the contested design are not similar.

44 According to settled case-law, the risk that the public might believe that the goods or services in question come from the same undertaking or from economically‑linked undertakings constitutes a likelihood of confusion. According to that case-law, the likelihood of confusion must be assessed globally, according to the perception that the relevant public has of the signs and of the goods or services in question and taking into account all relevant factors in the case, in particular the interdependence between the similarity of the signs and that of the goods or services identified (see GIORGIO BEVERLY HILLS, cited in paragraph 24 above, paragraphs 30 to 33 and the case-law cited).

45 The global assessment of the likelihood of confusion, in relation to the visual, phonetic or conceptual similarity of the signs in question, must be based on the overall impression given by the signs, bearing in mind in particular their distinctive and dominant components. The perception of the signs by the average consumer of the goods or services in question plays a decisive role in the global assessment of that likelihood of confusion. The average consumer normally perceives a mark or another distinctive sign as a whole and does not proceed to analyse its various details (see, to that effect, Case C‑251/95 SABEL [1997] ECR I‑6191, paragraph 23; Lloyd Schuhfabrik Meyer, paragraph 24 above, paragraph 25; and Case C‑120/04 Medion [2005] ECR I‑8551, paragraph 28).

46 It is in the light of the foregoing considerations that it must be examined whether the Board of Appeal was correct to find that there was a likelihood of confusion between the earlier mark and the contested design and that, consequently, the latter had to be declared invalid.

47 First, as regards the goods, the Board of Appeal correctly stated, at paragraph 28 of the contested decision, that the ‘cleaning devices’ in which the contested design is intended to be incorporated are included in the list of goods for which the earlier mark was registered, and that they are therefore identical to those covered by the earlier mark. Indeed, that is not disputed by the applicant.

48 Next, as regards the relevant consumer, it is clear that the goods concerned are everyday consumer items and that they are therefore directed at the general public, as the Board of Appeal noted at paragraph 26 of the contested decision. The earlier mark is a Community trade mark. Consequently, account must be taken, for the purposes of assessment of the likelihood of confusion, of the perception of the earlier mark and the contested design by the average consumer throughout the European Union, who is deemed to be reasonably well-informed and reasonably observant and circumspect.

49 In addition, as regards the visual comparison of the earlier mark and the contested design, it is apparent from paragraphs 25 to 29, 32 and 33 above that the geometric form, dimensions and shape of the earlier mark and the contested design are highly similar and identical in part.

50 The additions and differences are only of secondary importance, for the reasons outlined at paragraph 27 above. As is apparent from paragraph 30 of the contested decision, the differences between the earlier mark and the contested design essentially concern slight changes to relatively small details in the cleaning device as a whole and do not alter its overall shape.

51 The applicant submits that OHIM wrongly disregarded the fact that the earlier mark contains the word element ‘am’ and claims that, in the light of the fact that the three-dimensional shape of the cleaning device is devoid of distinctive character, the assessment of similarity can be carried out solely on the basis of that word element. OHIM contends, first, that that claim was never raised during the proceedings before OHIM and is therefore inadmissible and, second, that the word element is in any event illegible.

52 Without it being necessary to examine the question of admissibility of that claim, it must be stated that it cannot succeed. A sign which is so difficult to decipher, understand or read that the reasonably observant and circumspect consumer cannot manage to do so without making an analysis which goes beyond what may be reasonably expected of him in a purchasing situation may be considered to be illegible (see, to that effect, judgment of 2 July 2008 in Case T-340/06 Stradivarius España v OHIM – Ricci (Stradivari 1715), not published in the ECR, paragraph 34, and judgment of 11 November 2009 in Case T‑162/08 Frag Comercio Internacional v OHIM – Tinkerbell Modas (GREEN by missako), not published in the ECR, paragraph 43). In the present case, it is clear, as OHIM pointed out in its pleadings, that the word element ‘am’ is difficult to decipher given its size, position and lack of contrast in the graphic representation of the earlier mark. The average consumer will have even greater difficulty reading it because he does not proceed to analyse the various details of the mark when making a purchase (see, to that effect, SABEL, cited in paragraph 45 above, paragraph 23; Lloyd Schuhfabrik Meyer, cited in paragraph 24 above, paragraph 25; and judgment of 20 September 2007 in Case C-193/06 P Nestlé v OHIM, not published in the ECR, paragraph 34). Accordingly, because of its near illegibility, that word element will have no influence on how the average consumer visually perceives the earlier mark.

53 As regards the phonetic and conceptual comparison, the Board of Appeal was correct in finding, at paragraph 29 of the contested decision, that it could not, in the present case, make a phonetic comparison and a conceptual comparison between the earlier mark and the contested design. First, the earlier mark only contains an illegible word element and the contested design does not contain any. Nor do they lend themselves to brief, simple descriptions in words which could be compared phonetically. Second, neither the earlier mark nor the contested design evokes any particular concept, with the result that no conceptual comparison of the two can be made either.

54 It must be noted in this respect that the applicant has not presented any evidence to challenge the position of the Board of Appeal regarding the impossibility of comparing the earlier mark and the contested design conceptually and phonetically.

55 Finally, as regards the taking into account of the distinctive character of the earlier mark in the global assessment of the likelihood of confusion, the applicant claims without success that the minimum degree of distinctive character which OHIM conceded to the earlier mark derives exclusively from the word element ‘am’ and that the assessment of the similarity can be carried out solely on the basis of that word element. It stands to reason that the word element, the negligible character of which was demonstrated at paragraph 52 above, cannot of itself dominate the image of the earlier mark which the relevant public keeps in mind.

56 To that effect, the argument that the three-dimensional shape of a cleaning device is completely devoid of distinctive character cannot succeed either.

57 First of all, while it is true, as the Board of Appeal itself noted at paragraphs 32 and 33 of the contested decision, that average consumers are not in the habit of making assumptions about the origin of goods on the basis of their shape or the shape of their packaging and that it is doubtful whether the public considers the shape of a cleaning device as an indication of its origin, the fact remains, as indicated at paragraph 34 of the contested decision, that the earlier mark was registered and has not been declared invalid on the ground that it lacked distinctive character. It is necessary also to approve OHIM’s assessment that, since the earlier mark has been registered, it must be presumed that the shape that it is composed of is sufficiently unusual compared to the norms of the sector and sufficiently striking for it to be capable of fulfilling the essential function of a trade mark.

58 Next, the applicant does no more than claim that the mere reproduction of the shape of goods or that of their packaging is not generally perceived as an indication of the origin of those goods. She relies in this respect on the case-law according to which average consumers are not in the habit of making assumptions about the origin of goods on the basis of their shape or the shape of their packaging in the absence of any graphic or word element, and it may therefore prove more difficult to establish distinctive character in relation to a three‑dimensional mark than in relation to a word or figurative mark (Case C‑136/02 P Mag Instrument v OHIM [2004] ECR I‑9165, paragraph 30, and judgment of 17 December 2008 in Case T‑351/07 Somm v OHIM (Shelter for shade), not published in the ECR, paragraph 32).

59 As stated at paragraph 40 above, that case-law does not preclude the view that the reproduction of the shape of goods may be perceived as an indication of their origin.

60 Moreover, the applicant has provided no concrete evidence – such as examples of cleaning devices where the shape of the product has similarities to the shape of the earlier mark which was already used by competitors at the date of submission of the earlier mark – to support her assertion that the three-dimensional shape of the earlier mark has no distinctive character.

61 Lastly, it appears that the applicant’s arguments must be understood as meaning that OHIM cannot prevent the use of a design on the basis of the requirement of availability. It must be observed that the fact that there is a need for the sign to be available for other economic operators cannot be one of the relevant factors in the assessment of the existence of a likelihood of confusion (Case C‑102/07 adidas and adidas Benelux [2008] ECR I‑2439, paragraph 30).

62 It follows that the Board of Appeal did not err in considering that the earlier mark had at least a minimum degree of distinctive character.

63 In this respect, according to settled case-law, even in a case involving an earlier mark of weak distinctive character, there may be a likelihood of confusion on account, in particular, of a similarity between the signs and between the goods or services covered (see, to that effect, Case T‑112/03 L'Oréal v OHIM – Revlon (FLEXI AIR) [2005] ECR II‑949, paragraph 61; Case T‑134/06 Xentral v OHIM – Pages jaunes (PAGESJAUNES.COM) [2007] ECR II‑5213; and judgment of 31 January 2012 in Case T‑378/09 Spar v OHIM – Spa Group Europe (SPA GROUP), not published in the ECR, paragraph 22).

64 Consequently, the Board of Appeal was correct to consider at paragraph 35 of the contested decision that, taking into account the similarity of the contested design and the earlier mark and the identity of the goods covered by the earlier mark and the goods in which the design is intended to be incorporated, there is a likelihood of confusion in accordance with Article 9(1)(b) of Regulation No 207/2009 even taking into account the weak distinctive character of the earlier mark.

65 Therefore, the second plea in law, alleging breach of Article 9(1)(b) of Regulation No 207/2009, is unfounded.

66 In the light of all the foregoing, the action must be dismissed.

Costs

67 Under Article 87(2) of the Rules of Procedure of the General Court, the unsuccessful party is to be ordered to pay the costs if they have been applied for in the successful party’s pleadings. Since the applicant has been unsuccessful, it must be ordered to pay the costs, in accordance with the forms of order sought by OHIM and the intervener.

On those grounds,

THE GENERAL COURT (Seventh Chamber)

hereby:

1. Dismisses the action;

2. Orders Su-Shan Chen to pay the costs.

Dittrich | Wiszniewska-Białecka | Prek |

Delivered in open court in Luxembourg on 25 April 2013.

[Signatures]